Supporting Medically Fragile Children and Their Families

You are here

Before 11-month-old Leshawn even entered the classroom at the Early Childhood Lab School, Julia, the program coordinator (and lead author), and her staff (including Amy, the second author) wondered whether being in group care would be a good fit for him. Diagnosed at birth with a diaphragmatic hernia, Leshawn had a team of specialists working with him. He had been hospitalized for most of his early infancy and was being fed through a gastronomy tube (G-tube) which, his mother feared, might be yanked by another infant. Unwilling to let his mother leave his side, Leshawn showed intense separation anxiety.

If the program enrolled this medically fragile infant, staff would have to be aware not only of his medical needs but also of his unique social and emotional needs arising from hospitalization. Fortunately, Julia’s training in a specialty known as child life in hospitals enabled the program to include Leshawn in the classroom and tailor the curriculum to his needs.

An important home visit

Soon after the Lab School accepted Leshawn, his lead teacher, Monique, and Julia visited his home to meet with his parents, learn more about Leshawn and his needs, and ensure that everyone was in agreement on his education and care. Monique and Julia shared with his parents some common fears that infants Leshawn’s age have during transitions to group care and explained how the staff would handle them in the classroom.

Then, putting on her child life specialist hat, Julia pointed out some of the things in the daily routine that might trigger Leshawn’s fears (such as teachers’ use of gloves while diapering, which might remind him of hospital experiences). But more important, Julia and Monique listened. They wanted to learn about his family’s cultural and religious views and their hopes for their son’s educational experience—much the same as with any other home visit, but with a critical focus on gathering information about Leshawn’s medical requirements and related emotional needs.

The whole staff would work closely as a team to support this family and child as they made the leap to a group early education setting. Talking with his parents, Monique and Julia learned how to care for Leshawn’s G-tube and how to feed him and handle his reflux. They learned how his family soothed him. They built trust as they listened and asked questions about Leshawn’s care. This home visit was the longest of any to the children and families the school served. And when Monique and Julia wrote his care plan, it was the longest in the classroom. The plan reflected Leshawn’s special physical and emotional needs as well as his family’s wishes. In view of Leshawn’s separation anxiety, they also drafted a transition plan specifying that his mother stay with him in the classroom as long as necessary while he eased into trusting nonfamily members in this new setting. Understanding that it would be hard for Leshawn to trust nonparental caregivers turned out to be key in his eventual success in the classroom.

The child life specialist as the nexus of the care team

Because families are children’s first teachers, and because many families hold strong cultural and religious perspectives about how their children should be cared for, clear communication that begins before the child joins the program is critical. When a child faces significant medical issues, the family often experiences considerable stress about the child’s health and the family’s finances. Parents may also struggle with strong protective urges that make the transition to an educational setting more difficult than usual.

Because families are children’s first teachers, and because many families hold strong cultural and religious perspectives about how their children should be cared for, clear communication that begins before the child joins the program is critical. When a child faces significant medical issues, the family often experiences considerable stress about the child’s health and the family’s finances. Parents may also struggle with strong protective urges that make the transition to an educational setting more difficult than usual.

Connecting with families of medically fragile children means conducting an unusually comprehensive initial home visit and writing a detailed care plan—as Monique and Julia did for Leshawn. During the home visit, it is wise to also find out how much information about the child’s condition—if any—you may share with other families. To ensure continuity of care, ask the family for written permission to connect with the child’s medical specialists. The privacy of medical information is protected by federal law (HIPA A—the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996), and family consent must be obtained before medical professionals share any details with others. Once the child has been integrated into the classroom, devote extra attention to keeping the family updated on his or her progress with photos, anecdotes, and conversations. Although this is typically done for all children, with medically fragile children it is especially important to keep lines of communication open, increase family engagement, and build trusting relationships.

While child life specialists generally spend most of their time working with hospitalized children to normalize their experiences and support coping, hospital–school links can greatly improve the care seriously ill children receive as they move between settings. For example, when Leshawn was hospitalized earlier with respiratory difficulties, he encountered many masked faces—a necessity to minimize his exposure to germs. But Leshawn was far too young to understand the purpose of the masks, and not being able to see peoples’ faces often frightens very young children. A child life specialist would be aware of such fears and would share them with Leshawn’s family and teacher, along with activities to use at home and in the classroom to mitigate the fear. For example, initiating peekaboo games with familiar people wearing surgical masks might allow Leshawn to master this aspect of his hospital experience. For older children, adding real medical masks to the dress-up area for use during make-believe doctor visits is helpful.

Leshawn, being an infant, had limited ability to articulate his fears and needs beyond crying and clinging to his parents. Older children may have more complex fears and may ask challenging questions about their medical experiences. These sorts of questions are more likely to come up during medical play and art activities (Malchiodi 2006). While the classroom teacher is probably not the right person to answer medical questions (unless told by the parent or specialist what the child needs to know and how to say it in a developmentally appropriate way), passing along these questions to the family and the child life specialist and sharing observations with them are good ways to help the child find answers and means of coping.

To create opportunities for communication, the specialist can suggest activities for older children, such as making art using nonhazardous medical props (like cotton balls), engaging in water play with plastic syringes (without needles) and tubing, providing toy ambulances and doctors, and offering doctor and child puppets. These activities permit children to express their fear, anger, and ideas as they play in a judgmentfree setting (Oremland 1988). They can also help restore some control to a child. As one art therapist explained, “When the ill child engages in art making, he or she is in charge of the work—the materials to be used; the scope, intent, and imagery; when the piece is finished; and whether it will be retained or discarded” (Councill 2012, 222).

Child life specialists optimize care

With a medically fragile child, continuous coordination among educators, medical staff, and families is essential. Ideally, hospitals or early childhood programs would have on staff—or have access to—child life specialists who could facilitate coordination, ensure families are aware of all available resources, and support educators in caring for the fragile child. With the parents’ permission, the specialist could guide the teacher in adding developmentally appropriate medical information and activities to the curriculum.

According to the Association of Child Life Professionals, child life specialists “help infants, children, youth, and families cope with the stress and uncertainty of acute and chronic illness, injury, trauma, disability, loss, and bereavement. They provide evidence-based, developmentally and psychologically appropriate interventions, including therapeutic play, preparation for procedures, and education to reduce fear, anxiety, and pain” (ACLP 2017). Practicing professionals have completed coursework in the subject, gained clinical experience, and passed a qualifying exam. (For more details, see www.childlife.org/certification.)

Connecting with hospitals, specialists, and families

Even 1-month-old infants are hugely impacted by hospitalization, as they remember more than previously thought possible (Gopnick 2009; Rochat 2009). Hospital practices should reflect infants’ awareness and capacity to remember by providing as much contact with families as possible, as well as opportunities to build trust with medical caregivers and to relax and play. All infants develop understandings of and expectations for how people should act, based on their experiences (Johnson et al. 2010). Infants who have endured long hospital stays may perceive their caregivers as having the potential to harm them (i.e., with painful procedures) and think that their families have abandoned them (i.e., visiting only after work).

Toddlers and young children also may see unfamiliar hospital equipment and be terrified by people with no faces (i.e., wearing masks) who seem to enjoy giving shots and taking blood. Older preschoolers and school-aged children have better comprehension of the hospital environment and therefore are more realistic, but they still may fear procedures and be upset by temporary setbacks. Once toilet trained, for example, having to use a diaper again is a big step backward!

Reducing fear and stress

Children of all ages are negatively impacted by the fear and toxic stress that can come with illness and hospitalization—but their behavior may simply look like regression or acting out. To minimize fear and stress, child life specialists provide access to a playroom in the hospital that looks much like an early childhood classroom, with interest areas and child-led play. Specialists stay close by to provide a sense of security and to engage in therapeutic play, addressing children’s needs and modeling coping tools for children (and their families). No procedures are permitted in the playroom, so children can relax enough to play and learn with familiar playroom staff members. These staff members become a safe base for children, as they do not perform any medical procedures. For those children too ill to attend the playroom (such as those in isolation for a bone marrow transplant), specialists develop individualized play opportunities and work with the children’s families.

To design children’s programs and interventions, child life specialists rely on many of the same theorists and researchers that early childhood educators do. For example, using knowledge of physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development, specialists provide activities toddlers can do by themselves. Specialists help children master their stressful experiences through role play and making art. For example, the specialist might use a dollhouse and a toy ambulance to reenact arrival at the hospital, or draw a picture about the trip. So, what would the child life specialists caring for Leo and Leshawn do to support them in the hospital? A specialist might have engaged Leo in medical play using a doll who has similar tubing or scars to allow Leo an opportunity to gain mastery over his experience, and to provide an outlet for his emotional expression. Leo may have medical misconceptions that would be shared during this doctor play, and a child life specialist could help him and his family better understand what happened during his procedure. Perhaps Leshawn’s child life specialist would create musical instruments out of medical equipment, such as using medicine cups as shakers, to present medical equipment in a fun and nonthreatening manner, working with Leshawn in a child-friendly way to help him feel more comfortable with the things he sees. This kind of play can help children gain emotional control of frightening situations (Gaynard et al. 1998; Brazelton & Greenspan 2000; Salmela et al. 2010).

Teachers knowing that the hospital playroom and classroom are similar can enhance school-to-hospital connections, as many of the activities done in each location overlap. The hospital playroom is seen as safe space free of medical treatments, which can help children to feel safe when transitioning to their classrooms. Teachers connecting with the specialists who have supported a child in the hospital can ensure better continuity of care during the hospital stay throughout the patient’s discharge and transition back to the classroom by communicating about the challenges the child has experienced and suggesting ways to support the child in the classroom. Throughout these transitions, keep in mind that each child, his or her experience, and his or her response to stress and trauma is unique (NCTSN 2012). There is not one answer to how a child will or should behave in the classroom or hospital, and no simple answer to how children respond to threats, such as hospitalization, to their physical and mental health.

Finding a child life specialist

Child life specialists are generally affiliated with the main branches of hospitals, though they sometimes work in other settings. The Association of Child Life Professionals offers online resources to assist with locating a specialist (see www.childlife.org/child-life-profession/networking). Many hospitals have information about child life specialists on their websites.

When educators know of a child about to enter a hospital who might benefit from a specialist’s preparation and support, they should begin by asking the family. (Remember, to share details about a child’s medical needs, educators need the family’s signed permission.)

Connecting with families and absent children

Sometimes a child will be hospitalized for a long time, such as during a perforated appendix, chemotherapy infusion, organ transplant, inpatient rehabilitation following an accident, or a bout of pneumonia. When preschool-age or older children are away from the classroom but seek connection to classmates, tools such as Skype can be used to reconnect the children. This can support the child’s ability to cope and can help his or her classmates better understand the situation. Letter writing can also connect an absent child with the classroom and help build community. For younger children, exchanging photos is a way to stay connected; keeping images of the ill child in the room reminds peers that the ill child still exists and helps with the child’s return to the classroom.

A successful inclusion

Leshawn became integrated into the classroom slowly. Although he would not leave his mother’s side, he played with staff and with the student caregivers in the Lab School who were assigned to care for him. His worst time of day was diapering, because being laid on his back and being attended to by a person wearing gloves signaled to him that a painful medical procedure was about to begin. Initially, Monique and Julia asked his mother to change his diaper; later, they and other school caregivers let him feel the gloves before putting them on their hands.

They communicated with his mother by email nearly every day. They were able to identify other things in the classroom routine that might be stressors for him, such as adults’ blue shoe covers and the smell of bleach and other cleaners. While the school needed to continue these basic health and safety practices, being aware of Leshawn’s perspective helped staff and student caregivers be more sensitive and allowed him to transition at his own pace. To avoid the use of shoe covers, Monique and Julia encouraged everyone to wear socks. They tried to make the room smell of lavender instead of bleach. The goal when Leshawn was an infant was to make it clear that this setting was free of medical procedures and was very different from the hospital.

Gradually, Leshawn’s mother left him with Julia, and if Leshawn became upset, Julia took him out in the yard for one-on-one sessions watching squirrels and busses. It took time, patience, and training for Julia and Monique to help Leshawn manage and eventually reduce his terror in the classroom. Most of all, it took teamwork between Monique, his family, and Julia. After 25 weeks in the classroom, Leshawn had completely adjusted.

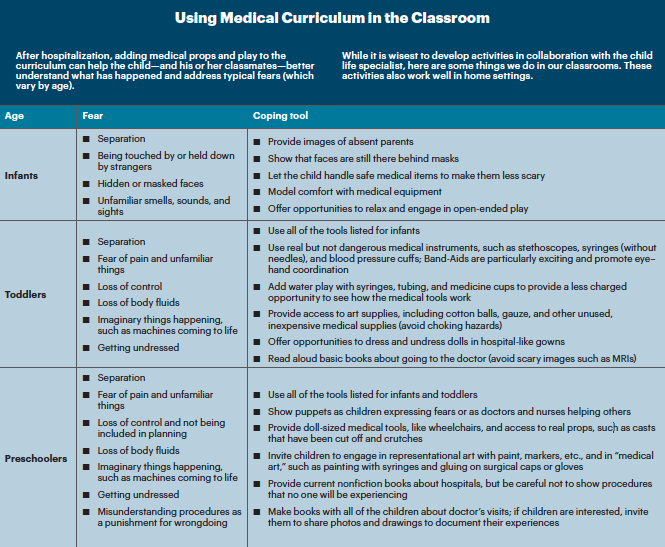

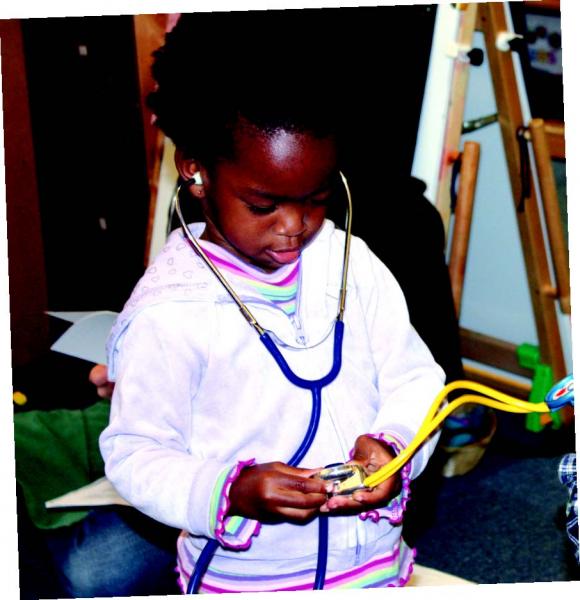

As Leshawn grew older, Julia and Monique adapted the curriculum with his needs in mind. When he was 2, they invited a parent who is a doctor to show the children her medical tools at circle time. For this visit, they invited Leshawn’s mother to join the class. They were worried that seeing a medical professional in the classroom would cause Leshawn to panic, but he astounded everyone by being totally fine. He was clear about the difference between the classroom and the hospital and felt safe to explore autonomously. When Julia added several real medical instruments—including stethoscopes, masks, plastic syringes (without needles), and Band-Aids—to the dress-up area, Leshawn was able to relax with the tools and play with them with his trusted caregivers and peers. (See “Using Medical Curriculum in the Classroom.”)

Helping Leo prepare for surgery

While Leshawn was the youngest medically fragile child to be included at the Lab School, he was not the only one. Leo joined the school at 4 years old. He had had heart surgery during infancy and was waiting to be scheduled for another open-heart operation sometime during the school year. Soon after Leo enrolled, his teacher observed him displaying fear about his doctor’s appointments by crying at transitions to and from home and school. He worried aloud about unplanned doctor visits. His teacher spoke with his mother and then asked Julia to speak with her.

During the meeting with Leo’s mother (which was scheduled while Leo was in class, so the conversation could be open), Julia’s goal was to listen first. His mother explained that Leo had not been told about the surgery but may have overheard her talking about it on the phone. (With Leo, the staff was able to tease out that he knew enough about the upcoming surgery to be scared, but did not know when it would happen; so every time he was picked up from school, he worried that he would be whisked off to the hospital.) Julia explained to Leo’s mother that older preschoolers have a need for control, and she offered some ways for him feel in control—for example, by meeting with a child life specialist who would prepare him for the procedure. (Leo’s mother had not heard of this service.) Julia stressed that the explanation had to be accurate so his experience would match the preparation. She suggested to his parents taking photos and making a scrapbook about his experience to share with his classmates. Julia connected Leo’s mother with his hospital’s child life team, and they prepared him for the surgery and supported his family throughout the event.

Julia also met with his teacher and spoke to his classmates about their friend’s experience using a doctor puppet. Leo’s teacher collected questions for the family from the children, and they answered classmates’ questions about hospitals.

Before Leo reentered the classroom, his parents and teacher prepared the other children for his return, addressing any misconceptions they had. (In this case, Leo’s appearance would not be much different; but if a child returns without hair, for example, preparing classmates to be supportive is important.) On his return, Leo and his classmates engaged in medical play in the dramatic play area and explored the roles of doctors and nurses. Leo was also offered opportunities to express his feelings in the writing and art areas.

Summing up: Communicate and collaborate

When a child is returning to the classroom post hospitalization, there may be moments when hard questions come up or when the child expresses strong emotions. Educators can use the following strategies to support the child, then revisit the conversation later (after consulting with a parent or specialist), if needed.

When a child is returning to the classroom post hospitalization, there may be moments when hard questions come up or when the child expresses strong emotions. Educators can use the following strategies to support the child, then revisit the conversation later (after consulting with a parent or specialist), if needed.

- Encourage the child to talk about his or her feelings or concerns. Write them down to share with the family and the child life specialist.

- Assess the child’s perceptions and understandings by asking questions such as, “I wonder why your doll needed to go to the doctor?”

- Guide play by asking about the “patient” (e.g., a doll or stuffed animal) to further assess the child’s understandings and emotions surrounding the medical experience.

- Reinforce correct information about medical care, if you know the correct information. For instance, a teacher may say, “Giving a doll a shot helps her get medicine the best and quickest way.”

- Be careful not to give incorrect information or too much information. It is better to say, “I don’t know; I’ll have to find out,” than to add to a child’s misconceptions. Help the child or child’s family get answers to questions about specific procedures from the hospital’s child life specialist.

- When the child says something about what he or she thinks might happen, reflect or repeat the child’s comments and expressions to the child to clarify and to help the child feel heard (e.g., “When the bear feels sick, he cries.”). This helps shape the child’s ideas toward correct information when misinformation is revealed.

- If a child asks about death, be careful to respect the family’s wishes, culture, and religion. Do not share your own religious beliefs, and be sure to tell the family about the child’s questions.

- Share your observations about the child with the family and child life specialist, and get feedback frequently, so you’re all in agreement on how to support the child.

Including in your program children who have experienced extensive medical procedures may seem daunting. Keep in mind that they are still children and can benefit from using play and art to express their ideas and needs, just like children who have not had major medical experiences. Working closely with a care team that includes parents (or guardians) and a child life specialist can enhance the child’s physical and mental health across settings. Adding real, safe medical play props to the curriculum is an excellent way to value the experiences and needs of children who have been hospitalized. This has the additional benefit of preparing the other children in the room for possible future experiences with illness or injury. Being aware of the common fears and needs of children at different ages, and having access to a child life specialist, when necessary, is a great way to support medically fragile children in educational settings.

Resources

Association of Child Life Professionals

www.childlife.org

National Child Traumatic Stress Network

“Resources for Parents and Caregivers”

www.nctsn.org/resources/audiences/parents-caregivers

UMass Memorial Medical Center

“Helping Children Cope with Health Care Experiences”

www.umassmemorialhealthcare.org/umass-memorial-medical-center/services-t...

References

ACLP (Association of Child Life Professionals). 2017. “The Child Life Profession: What Is a Certified Child Life Specialist?” www.childlife.org/child-life-profession.

Brazelton, T.B., & S.I. Greenspan. 2000. The Irreducible Needs of Children: What Every Child Must Have to Grow, Learn, and Flourish. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo.

Councill, T. 2012. “Medical Art Therapy with Children.” Chap. 16 in Handbook of Art Therapy, 2nd ed., ed. C.A. Malchiodi, 222–40. New York: Guilford.

Gaynard, L., J. Wolfer, J. Goldberger, R. Thompson, L. Redburn, & L. Laidley. 1998. Psychosocial Care of Children in Hospitals: A Clinical Practice Manual from the ACCH Child Life Research Project. Bethesda, MD: Association for the Care of Children’s Health.

Gopnick, A. 2009. The Philosophical Baby: What Children’s Minds Tell Us about Truth, Love, and the Meaning of Life. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Johnson, S.C., C.S. Dweck, F.S. Chen, H.L. Stern, S.J. Ok, & M. Barth. 2010. “At the Intersection of Social and Cognitive Development: Internal Working Models of Attachment in Infancy.” Cognitive Science 34 (5): 807–25.

Malchiodi, C.A. 2006. The Art Therapy Sourcebook. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

NCTSN (National Child Traumatic Stress Network) Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma Task Force. 2012. “The 12 Core Concepts: Concepts for Understanding Traumatic Stress Responses in Children and Families.” Los Angeles, CA, & Durham, NC: UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. www.nctsn.org/resources/audiences/parents-caregivers/what-is-cts/12-core....

Oremland, E.K. 1988. “Mastering Developmental and Critical Experiences through Play and Other Expressive Behaviors in Childhood.” Children’s Health Care 16 (3): 150–56.

Rochat, P. 2009. Others in Mind: Social Origins of Self-Consciousness.New York: Cambridge University Press.

Salmela, M., S. Salantera, T. Ruotsalainen, & E.T. Aronen. 2010. “Coping Strategies for Hospital-Related Fears in Preschool-Aged Children.” Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 46 (3): 108–14.

Photographs: © Julia Luckenbill

Julia Luckenbill, MA, is the director of programming for the Davis Joint Unified School District's parent participation nursery school at the Danbury site.

Amy Zide, MS, CCLS, is a certified child life specialist at UC Davis Children’s Hospital, in Sacramento, California. Amy works in a general pediatric unit, serving patients of all ages and their families, helping them to better cope with the challenges of illness and hospitalization. Previously, she served as a teaching assistant in Julia Luckenbill’s classroom while completing her undergraduate degree. [email protected]