Being a Helper: Supporting Children to Feel Safe and Secure after Disasters

You are here

Four-year-old Sophie has never had trouble falling asleep during rest time. Even after wildfires forced her family to flee their home a month before, Sophie slept well, hugging her stuffed penguin, Pablo. Lately, though, Sophie has become anxious as rest time approaches. It’s almost as if she is scared to fall asleep.

Children like Sophie, who have been traumatized by a disaster, are unfortunately not unique. Disasters can be defined as unexpected, disturbing, and stress-inducing events. They may be natural, like hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes, or the result of human intervention, like mass shootings.

Children who are directly affected by these events are our first point of concern, since their trauma is often intensified by grief. We need to keep in mind, though, that all children can be affected. Following 9/11, children playing in block centers in a Department of Defense preschool program in Japan and a Florida Head Start program were observed flying toy airplanes into block towers. After the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, preschoolers in programs nowhere near Connecticut were “shooting” one another during dramatic play. None of these children had direct ties to the tragedies, yet all were impacted.

Mr. Rogers famously talked about what he was told as a child when he saw scary things on the news: “My mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’” Early childhood teachers are the frontline helpers who can help traumatized children rebound.

How do disasters affect children’s well-being?

Trust and security are the foundations of healthy development. To explore the world and learn, children need to have secure, trusting relationships with the adults around them and faith that they will keep them safe. Families and schools work hard to send children the message that their needs will be consistently met in places that are safe, secure, and reliable.

Children who witness disasters firsthand can feel deep aftereffects. The more devastating the experience, the deeper the trauma.

Children who witness disasters firsthand can feel deep aftereffects. The more devastating the experience, the deeper the trauma.

Children’s responses to trauma closely reflect the way their parents respond. If parents communicate that they are coping with the situation and everything will be okay, children are likely to be more resilient.

Age also influences how a child responds to trauma. Understanding child development provides insight into how a child is processing a situation and dealing with fears. For example, young preschoolers are beginning to separate fantasy from reality. You can help them figure out whether their fears are based on reality and understand that nightmares don’t mean that bad things are still happening.

How children may react to traumatic events

Following a disaster, children are likely to be anxious, stressed, or depressed. If they’ve been directly affected by the disaster, they’re also exposed to family members’ grief and fear.

Children may immediately show symptoms of stress.

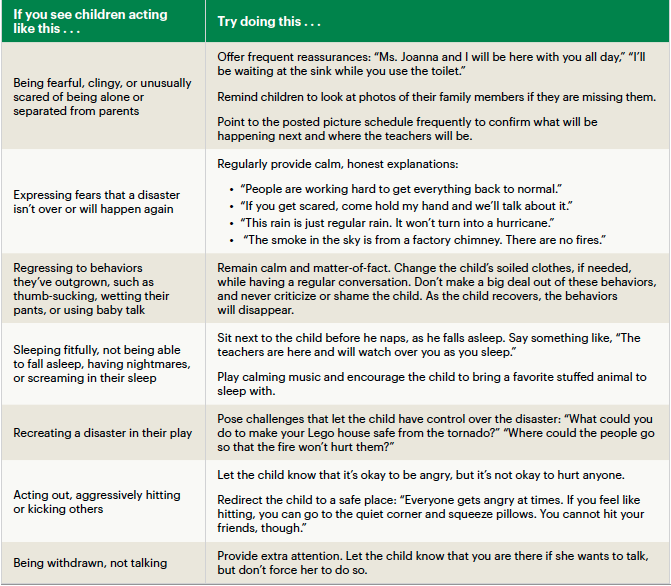

Or, like Sophie, children’s reactions may be delayed for weeks or even months. Observe children daily, and watch for symptoms of trauma. Use the chart below to help you address children’s needs.

Supporting families through crises

It’s important that teachers and parents partner in a joint recovery plan after a disaster. Every day, let families know how their children are doing. Allow families extra time to stay with their children at drop-off and pickup. If families have had to relocate, lend them books and stuffed animals.

Families and programs can apply similar strategies. Copy and distribute “11 Tips for Helping Children Who Have Experienced a Disaster” (below) to families. While adults should admit that the situation was frightening and that there are still challenges, they need to emphasize that they are in control of the situation and things will be okay. Children need constant reassurance that they are safe and secure.

Share with families the symptoms they should be looking for that indicate their child is stressed or anxious. Point out that regressive behaviors like thumb-sucking and bed-wetting are normal and temporary. Alert parents to physical signs of internalized stress, such as stomach cramps or headaches. Advise them that most children bounce back soon, but some may suffer lingering effects and require professional counseling. Consult with your program director or school counselor about children and family members whom you are particularly concerned about.

Children who are not directly exposed to a disaster may also feel anxiety and stress, especially if the news and adult conversations focus on the disasters. Share with families the importance of limiting children’s exposure to the news and TV. Constant reminders of a disaster raise anxiety. Families need breaks from the news to start healing.

Remembering yourself

Teachers may also experience anxiety and depression. Dealing with children’s and families’ fears is stressful. You might feel vicarious trauma—secondary trauma that results from witnessing others’ pain and terror. You might feel anger, have headaches, or want to avoid particular people or work obligations.

If you were involved in the disaster, you have your own trauma. Additionally, you may be burdened by dealing with cleanup, insurance companies, and doctors.

If you’re suffering, connect with colleagues or seek a therapist. It’s important that you don’t feel isolated; talk with others and develop coping strategies. Exercise, dance to your favorite music, call a friend. You must take care of yourself so that you can help others.

Conclusion

You play a huge role in helping children rebound from disasters. But remember: you’re not alone. NAEYC has useful resource lists on coping with stress and violence (NAEYC.org/our-work/families/coping-with-violence). You can also post questions or join discussions at Hello (hello.NAEYC.org/home). When it comes to helping young children recover from disasters, we’re all in this together.

Additional Resources

“Helping Children After a Disaster.” American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP)

www.aacap.org/aacap/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/Facts_for_Families_Pages/Helping_Children_After_A_Disaster_36.aspx

“Kids and Disasters: How to Help Them Recover,” by Betty Lai. The Conversation

https://theconversation.com/kids-and-disasters-how-to-help-them-recover-59032

“Psychological Effects of Disaster on Children,” by Mark Feldman. The Hospital for Sick Children

www.aboutkidshealth.ca/En/HealthAZ/FamilyandPeerRelations/AttachmentandEmotions/Pages/PsychologicalEffectson.aspx

“PTSD for Children 6 and Younger,” by Michael Scheeringa. US Department of Veterans Affairs. www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/ptsd-overview/ptsd_children_6_and_younger.asp

“When Students Are Traumatized, Teachers Are Too,” by Emelina Minero. Edutopia.

www.edutopia.org/article/when-students-are-traumatized-teachers-are-too

The Mister Rogers Parenting Book: Helping to Understand Your Young Child, by Fred Rogers. Philadelphia: Running Press.

Laura J. Colker, EdD, is president of L.J. Colker & Associates, in Washington, DC. She is an author, a lecturer, and a trainer in early childhood education with 40 years of experience. [email protected]