“Is There a Chick in There?” Kindergartners’ Changing Thoughts on Life in an Egg

You are here

“Is there a chick in there?”

“I know there is a chick in there.”

“No, it came from the grocery store.”

“There might be a chick in there. . . .”

“No, it’s cold. You need to keep the egg warm.”

The children in Deborah Halls’s full-day kindergarten class are discussing a dozen eggs in a carton brought in from a grocery store. Most of them think there could be a chick inside if the eggs are kept warm enough.

“If there is a chick, we should use sunlight to keep it warm.”

“I’m going to keep it warm in my sleeve.”

“Is there a flashlight? Farmers look inside with a flashlight.”

When this debate took place, Debbie was teaching a combined junior/senior kindergarten (with children 3 to 5 years of age) in an urban public elementary school of 300 children, in Toronto, Canada. There were 24 children in her class, a few with special needs, and most children were from Asian or Caucasian backgrounds. Three were just beginning to learn English. While some schools in the Toronto metropolitan area are highly diverse, others—such as this school—show concentrations of specific racial and ethnic groups. This school has some economic diversity, however, as high proportions of both professional and working-class families live in the neighborhood around the school.

Debbie responded to the children’s interest in keeping the eggs warm by bringing in a gooseneck lamp and a flashlight. The children experimented with various ways to keep the eggs warm in hopes that a chick just might hatch. The children watched the carton of eggs, moved the light closer and watched again, held eggs in their hands or sleeves to warm them, looked closely with the flashlight, and discussed when they might hatch. They kept up the warming plan for days. Nothing happened. In following the children’s ideas (though she knew they were inaccurate), Debbie had activated the children’s curiosity, interest, and engagement.

This activation began with a parent wanting to share her family’s Greek traditions around eggs and Easter. She and the children played games with eggs and decorated them. Debbie observed the children’s curiosity about what was inside the eggs and brought in the carton of eggs in response. Debbie’s approach to curriculum is to respond to children’s curiosities and thoughts in ways that allow those questions and curiosities to expand. She co-constructs with children and colleagues an emergent curriculum (Wien 2014, 2008). The children’s intense interest led her to plan a chick-hatching project.

A quiet gentleness came over the class

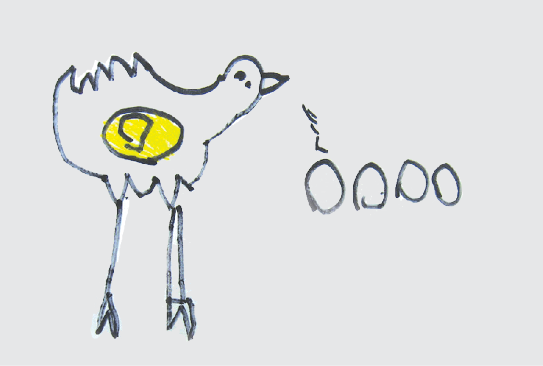

Debbie obtained fertilized eggs, an incubator, books, and stories on the development of chicks (see “Children’s Books about Eggs and Chickens”). She set up a center around the incubator and established ground rules with the children to keep the eggs safe. Two children at a time could visit the center to sit by the incubator and read stories to the eggs, or sing songs, or talk to the eggs. They could also draw pictures of what they observed or what they hoped for the eggs. While drawing, the children said things like, “I’m drawing the yolk, it’s inside the egg. It’s when the body is not even a chick yet.”

Debbie found that everyone wanted to be close to the eggs and later the chicks, and that the presence of eggs in the incubator helped the children be calm. Debbie’s notes, for example, comment on Colton, a very active boy who “jumps, rolls, and climbs on everything”:

Colton role-played how he would take care of the chicks when they hatched. He sang to the eggs, read to them, and found ways to stay close at all times. He took on a very soft and gentle demeanor and was calm. When the chicks were born he often said he was tired and would lie down beside the chick playpen so he could continue to observe and be close to them.

In Colton’s response, and in that of others who sang and read to the eggs, we saw that levels of deep feeling had been activated in the children. Their empathy and tenderness are fuel that keep engagement and learning intense. Such emotional engagement also assisted them with self-regulation, which is, in part, the capacity to stay calm, alert, and focused (Shanker 2013).

Each day of the 21-day waiting period, Debbie added a photograph to a poster in the center showing the growth of the embryos inside the eggs and talked about what was happening. Debbie was careful to provide accurate information about chick development. The children were curious about what the eggs looked like inside; some painted pictures of what the chicks might see. One child imagined the growing chicks could see rainbows on the inside of their shells.

Drawing a rainbow inside the egg.

An inquiry

Like many educators, Debbie is as interested in the children’s feelings and theories about what they are learning as she is in what they appear to have learned. She enjoys following the meaning that children are making of their experiences and she wondered how the children thought the chick happened to be in the egg. This was her inquiry into the children’s meaning making, which she conducted while she facilitated their inquiry into how chicks develop. Cognitive scientists tend to think of meaning making or understanding as having two intertwined components that cannot be separated: one is what we think about something and the other is how we feel about it. We know that feelings influence thinking, as they help direct our sense of how valuable something is to us. Without a clear sense of the personal value of something, decisions are much more difficult to make (Damasio 1994).

Following the children’s ideas, Debbie activated their curiosity, interest, and engagement.

The children understood that a chick hatches from an egg, but Debbie wondered how they thought it arrived there in the first place. This is a difficult question to ask. She considered asking, “How does the chick get into the egg?,” but thought this would be a leading question—suggesting that the chick “gets in” the egg. She tried several ways of wording the question. The one that sparked children’s thinking and opened up their ideas was, “How does it happen that a chick is in the egg?” Having found a question that generated ideas, her inquiry was under way—and she was confident that knowing the children’s ideas would give her a good baseline for future planning.

The Children’s First Theories in Drawings and Words

Calvin: Open the egg. Put the chick inside.

The chick closes the egg from inside.

John: The chick rolls up in a ball and

the mother puts them in [the egg].

Adam: The farmer puts the chick

in the egg, then he runs to the mom to

give her the egg before it hatches.

“How does it happen that a chick is in the egg?”

While waiting for the chicks to hatch, Debbie talked each day with the children about the changes occurring inside the egg, showed them illustrations of these changes, and discussed chick embryo development with the children. Over this three-week period, she managed to sit with most of the children individually three times to repeat her question, “How does it happen that a chick is in the egg?” To support the children in expressing their thoughts, she discussed the question with each child in a quiet spot (sometimes near the incubator or sometimes in a small room off the classroom) and asked them to draw their ideas. She also noted the length of time that each child spent drawing his or her theory on each occasion. The three children who spoke little English chatted with a Mandarin interpreter as they drew.

Debbie hung the children’s drawings in the classroom, alongside her summaries of their theories, for the children’s reflection. How the chick happened to be in the egg became a topic of conversation among the children, as Debbie overheard children’s theories on three different occasions during playtime. Over the course of the 21 days of looking, reading, talking, and drawing, startling changes occurred both in what children said and in what they drew.

A surprise

Most of the children’s first thoughts were remarkable. Although Debbie knew that the children did not yet grasp biological realities, she was still surprised by their initial ideas and excited to share them with others. It was a good reminder that putting photographs of reality in front of children does not mean they will understand them.

Here is a sample of the children’s initial thoughts on the question, “How does it happen that a chick is in the egg?”

“The chick squeezes the egg and a hole opens.”

“The chick knocks the egg open with his beak and gets in the tiny hole that only he can see.”

“The egg comes from the farmer. The farmer finds it in the field and pulls the egg open and the chick jumps in.”

Debbie documented the thoughts of each of the 24 children. Five thought the farmer put the chick in the egg; eight thought the chick climbed in by itself; three thought the mother hen put the chick in the egg; and one said it grew in the ground. Several children thought the mother hen ate the egg first, before laying it. One child avoided the question by saying it was magic. Of the 24 children, five had a notion of the chick developing inside the egg, as in, “He starts off as a yellow feather and then he grows.”

Debbie found the children authoritative and authentic in their theories:

I found it intriguing that they had such highly imaginative ideas and such intense belief. Where did these ideas come from and why were they so definite? I wanted to know more.

Shifting theories

The following four examples illustrate how children’s thinking changed from one discussion to the next. They illustrate some of the ways thinking moves, shifts, and is unstable as it is forming.

-

Adam shifted from “The farmer puts the chick in the egg, and then he runs to the mom to give her the egg just before it hatches” to “The chick develops in the egg. It has to develop for 21 days and if they develop fast, then it will hatch quicker.”

-

Daniel shifted from “The farmer shakes the egg around and the chick jumps in” to “The mother hen puts the egg inside. Then the egg comes out of her. The chick is inside the egg. He eats the yolk.”

-

Mossy shifted from “The chick knocks the egg open with his beak and gets in the tiny hole that only he can see” to “The egg makes the chick and it builds it in very tiny pieces at the bottom of the egg.”

-

Marley shifted from “It goes whoosh, ouch, ouch, and then it gets in” to “The mama hen sits on the nest and then the hen lays the egg. It transforms inside the mother. Then the egg is warmed: we put it in the incubator.”

When the drawings and theories were hung on the walls, Debbie held small group discussions in which the children shared their theories and interpretations of how the chick happened to be in the egg; she felt this process was instrumental in changing their theories. Clearly, the children shifted their theories remarkably over the three occasions when each drew their theory. The change in theories tended in the direction of accurate explanation but was inconsistent and partial. Nonetheless, the children were constructing a base of understanding that would support deeper learning in later grades.

The time spent in drawing increased each time Debbie invited a child to share his or her theory. For example, Hailey spent 15 minutes on her first drawing, 23 on her second, and 63 on her third; Rachel spent 12, 17, and 19 minutes, respectively. As the children spent more time on their drawings, their explanations also became more expansive, with stronger articulation of ideas, and more precision and detail. Although the added depth, detail, and accuracy were remarkable, they were also clearly a result of learning, not children’s biological development, since they occurred over three weeks.

How does learning occur?

Debbie felt there were moments when the children’s ideas changed even as she was talking with them, as this conversation with Savannah shows.

Debbie: How does a chick happen to be in an egg?

Savannah: It crawls in.

Debbie: How could a chick crawl in when it starts as a little speck? How do you think it might happen?

Savannah: I think it walks in.

Debbie: You can’t even see legs in the pictures. You only see the yolk and then the chick starts growing. How do you think it gets in there?

Savannah: I think it walks in.

Debbie: Does the mother hen have anything to do with it at all? Do you remember seeing pictures of a hen?

Savannah: I have. I saw a picture of the mother hen, the hen is sitting on the eggs, keeping them warm.

Debbie: What do you think is inside the egg?

Savannah: A chick!

Debbie: So, Savannah, first you said the chick crawls in the egg, and now you said that the hen warms the egg and the chick is inside the egg. Which one is right?

Savannah: The amazing one! The one where I changed my mind! I had an idea and I changed my mind. The hen actually lays the egg in her nest and the chick is inside.

In local documentation study groups, there were several discussions about this conversation. Some colleagues saw the conversation as teacher directed. Others saw it as indirect facilitation, with Debbie scaffolding the conversation without giving an answer. We found the conversation raised questions about the adult’s role and that this lack of agreement tends to widen perspectives. Lack of agreement keeps everyone thinking and considering, reluctant to be too certain about when learning has occurred. For teachers, knowing with certainty leads to taking that knowledge for granted—as unquestioned—and unquestioned knowledge prevents reflecting, thinking, and inquiring. We believe questioning is a part of a democratic process in education—a chance for multiple perspectives to be considered.

The children were constructing a base of understanding that would support deeper learning in later grades.

Thinking about thinking

The children themselves realized their theories were changing. Debbie had conversations with some children individually about these changes, asking each time, “What changed your thinking?” Here are some of the children’s responses.

“My brain changed it. I have a clock in my head and my mind changed when I was thinking.”

“I thought of something different. I changed my batteries and touched my forehead and my mind changed.”

“I was looking at a book and then I changed my mind.”

“I dreamed about it when I was sleeping, and then when I woke up I changed my mind.”

“I just found a better idea from my brain; my brain told me this.”

“I felt my idea was a little bit silly, so I got a great idea from my head.”

We see the children offering machine metaphors (clocks, batteries) in the same way adults use such metaphors, and also identifying the brain or the head as the source of their thinking. Additionally, the fact that children evaluate their ideas (“I felt my idea was a bit silly”) at a kindergarten level is important to recognize. Both the freedom to have an idea and the right to change it are important to children’s sense of participating in learning.

Significant moments of learning for the educators

The way Debbie approached her inquiry revealed things that adults might not have imagined about children’s thinking. Studying the documentation that Debbie generated (three sets of conversations and drawings for 24 children) reveals the flow of children’s thinking; like a river, their theories turn, twist, and sometimes swirl in place as they try out new ideas.

Debbie said that the most significant moments of learning during her own inquiry into the children’s thinking centered on how the project revealed different types of children’s learning. For this article, Debbie and I chose three aspects to share—drawing as an alternative means of communication; changing ideas through conversation; and the synergistic effects of talking and drawing with an empathic listener alongside.

Drawing as an alternative means of communication

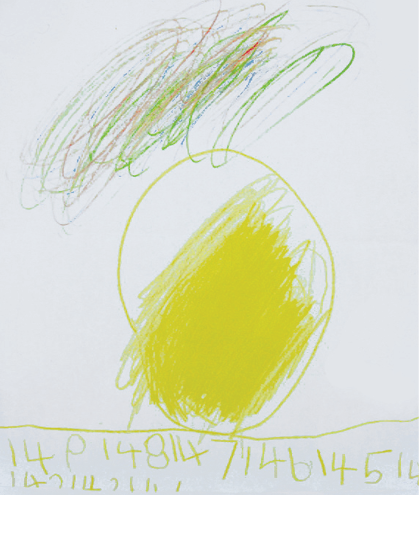

Ming was a dual language learner at the start of the school year, with little understanding of English. She had no easy way of communicating with others, beyond her Mandarin interpreter. Her first words here are translated by the interpreter, yet suddenly she was using English words to describe her later drawings.

Debbie and her principal, Mary Patrick, both thought that it was the process of drawing, and thinking about the question through drawing, that allowed Ming an opening with which to find vocabulary in English. Without drawing, they would not have had access to her thinking. Mary said, “I believe her drawing provided the vehicle to express herself with words.” In Ming’s case the process of drawing acts as a scaffold that supports speech.

Ming’s first drawing (3 minutes). “Click open a hole and went inside.”

Ming’s second drawing (10 minutes). “The chick is hatching in her nest.

The mommy chicken is going to come back. The baby chick is sleeping.”

Ming’s third drawing and theory (12 minutes).

“The hen eats the egg. Then it comes out of her.”

Changing ideas through conversation

A second type of learning was evidenced by Savannah’s example, in which she changed her theory in the midst of conversation with Debbie: in this case, dialogue was the vehicle through which a shift in thinking occurred. It seemed as though Debbie’s questions reminded Savannah of the information she had heard and seen over the previous weeks. What is interesting here is the child’s excitement, exclaiming how amazing her new idea is. Again, emotion is activated and assists children in holding their focus. As well, thoughts accompanied by strong emotion are remembered.

Enhancing ideas by speaking, drawing, and being listened to

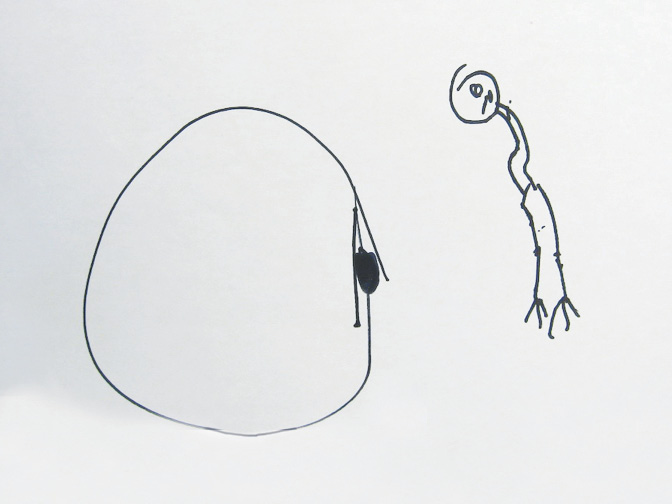

With some children, their theories were clarified by their drawings, as in the case of Colton. In his first drawing, which lasted two minutes, Colton drew isolated marks with some closed forms covering the page. He said in response to Debbie’s question, “The mama gives the chick milk and then it goes in the egg.”

For his second drawing, his theory stayed the same. Yet the marks on the page show more clearly separated forms in addition to other marks, and he spent four minutes drawing—twice the engagement of his initial attempt.

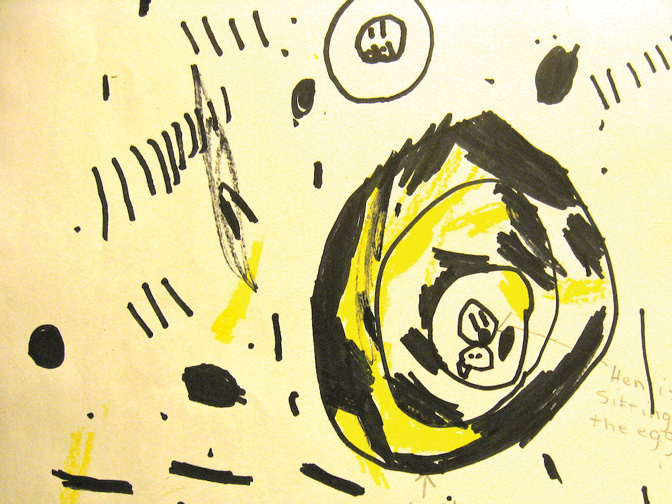

His third drawing (on two different papers, which Debbie combined onto a single background) is markedly different, as is his theory. In this instance, the time spent thinking and drawing increased yet again by 50 percent, to six minutes. Colton’s new theory was, “Mama was lonely and the Dad was lonely. Then they found each other and got married. Then the Dad put a seed in the mom and an egg grew. She laid her egg.” His drawing, this time of clearly articulated hen and rooster, smiling lovingly at each other, shows the hen with two eggs inside her, and the rooster with a plant-like structure holding a seed.

We can see the accuracy of Colton’s new thinking, and also its limits as he shows us his notion of the seed in the rooster as a plant (which is, at least, logical). Yet from intentional but loosely drawn parts in his first two drawings, he suddenly produces recognizable hen and rooster forms, with eggs inside the hen and a plant with seed inside the rooster. It is nothing short of astonishing. Through this in-depth, informative exploration of chicks, the children’s thoughts and capacities to express them changed with incredible speed.

Colton’s first drawing.

Colton’s second drawing.

Colton’s third drawing.

Metacognitive awareness of how quickly thinking shifts

Trying to follow ideas as they are changing, as children are learning, is like trying to follow drops of water in a fast-moving stream. When does an idea shift in an individual? When does it remain fixed? Does it shift because of any single factor or is it many aspects happening at once that leads a child to see a different possibility? How much does the environment contribute to provoking children to alter their ideas, their theories about how something happens in the world? How could we possibly be aware of all the shifts in all the children? These are questions that probably cannot be fully resolved. Yet, through intentional questions, discussions, and drawings, children’s changes in thinking can be perceived and encouraged (Gallas 1995).

Through intentional questions, discussions, and drawings, children’s changes in thinking can be perceived and encouraged.

Debbie’s combination of classroom processes—questions that generate theories, books and photos that provide new information daily, drawing and talking out theories, revisiting theories in light of new information, and sharing and conversing about theories—allows rapid shifts in thought and fosters marked increases in understanding and expression among the children. The children have deeply engaged emotionally and intellectually. Part of the brilliance of Debbie’s method is that the children appear to have driven this learning themselves. Yet it is the conditions Debbie provided in the classroom—including the care she took in formulating a provocative question and in creating multiple opportunities to digest and make meaning of new information—that revealed the children’s thinking and supported shifts toward more accurate understanding and more specific, elaborate expression.

References

Damasio, A. 1994. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam.

Gallas, K. 1995. Talking Their Way into Science: Hearing Children’s Questions and Theories, Responding with Curricula. New York: Teachers College Press.

Shanker, S. 2013. Calm, Alert, and Learning: Classroom Strategies for Self-Regulation. Toronto: Pearson.

Wien, C.A. 2014. The Power of Emergent Curriculum: Stories from Early Childhood Settings. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Wien, C.A., ed. 2008. Emergent Curriculum in the Primary Classroom: Interpreting the Reggio Emilia Approach in Schools. New York: Teachers College Press; Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Children’s Books about Eggs and Chickens

An Egg Is Quiet, by Dianna Hutts Aston; illus. by Sylvia Long. San Francisco: Chronicle.

The Egg, by Pascale De Bourgoing; illus. by P.M. Valat. New York: Scholastic.

The Perfect Nest, by Catherine Friend; illus. by John Manders. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick.

Tillie Lays an Egg, by Terry Golson; photographs by Ben Fink. New York: Scholastic.

Chickens Aren’t the Only Ones: A Book About Animals Who Lay Eggs, by Ruth Heller. New York: Puffin Books.

From Egg to Chicken, by Robin Nelson. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner.

Chick, by Angela Royston. See How They Grow series. New York: DK Publishers.

Photographs: © Getty Images; courtesy of the authors; Drawings: courtesy of the authors

Carol Anne Wien is professor emerita and senior scholar in the faculty of education at York University, in Toronto, Canada. She is widely known for her work on emergent curriculum and pedagogical documentation, inspired by the Reggio Emilia experience. She is the author of The Power of Emergent Curriculum: Stories from Early Childhood Settings and several other books, editor of Emergent Curriculum in the Primary Classroom: Interpreting the Reggio Emilia Approach in Schools, and coauthor, with Karyn Callaghan and Jason Avery, of Documenting Children’s Meaning. She speaks frequently at conferences and workshops across Canada and the United States and tries constantly to build the arts into daily life.

Deborah Halls, MEd, is a kindergarten teacher with the Toronto District School Board, in Toronto, Canada. She has been published in the journal Canadian Children and also coauthored the chapter “Wire Bicycles: A Journey with Galimoto” in Wien’s edited collection, Emergent Curriculum in the Primary Classroom. Using emergent curriculum approaches that offer rich, relevant experiences to young children, Deborah has developed expertise in thoughtfully questioning children, allowing them to develop their theories about the world.