Reflecting across Borders: Palestinian and US Early Childhood Educators Engage in Collaborative Science Inquiry (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the article | Ben Mardell, Voices Executive Editor

Emerging technologies are making international communication, and thus international collaboration, increasingly feasible. Still, barriers of language, culture, and time zone complicate such projects. By sharing the experiences of Palestinian and US early childhood educators involved in a joint project aimed at promoting meaningful early science teaching and learning, this article provides the rationale for undertaking such work and strategies for making such projects fruitful.

“Reflecting across Borders” will be of interest to educators not in a position to currently undertake an international collaboration, as well. From a professional development perspective, it is important to note how the levels of reflection of those involved in this project—individual teachers, local groups, and the entire research team—amplified the learning power of the work. Such reflection can be replicated between two schools (or even two classrooms).

From a teacher advocacy perspective, the power of teacher research to make visible (or audible) teachers’ voices and expertise is clear. And from a teacher researcher perspective, “Reflecting across Borders” is an exemplary piece of work, one that should be included on the syllabuses of every teacher research course.

Given the widening disparities in science achievement in many countries as children move into the elementary school years and beyond, it is imperative that early childhood educators understand how to promote inquiry-based science learning for the 21st century (Bradley 2016) that builds on children’s natural sense of curiosity and discovery (Maltese & Tai 2010; Engel 2011). There is growing evidence that despite potential challenges, the need for teachers to integrate meaningful, inquiry-based science experiences in the curriculum is essential. Important recent work has examined children’s understanding of nature (Taylor & Kuo 2006; Williams-Siegfredsen 2012; Meier & Sisk-Hilton 2013; Parnell, Downs, & Cullen 2017), critical links between content knowledge and the development of abstract reasoning (Metz 2008), and connections between science learning and multilingual development (Moje et al. 2001; Gort & Sembiante 2015; Evans & Avila 2016).

By providing young children with both unstructured and structured science experiences, teachers support them in building an understanding of the natural world that allows children to engage in increasingly complex investigations and knowledge building over time (Gelman & Brenneman 2004). Further, at a time when access to science and inquiry experiences is increasingly lacking in children’s lives outside of school, making time and space for science activities as part of the school program has become critical (White 2006). Finally, early experiences with science and nature contribute to children’s future interest in the sciences (Maltese & Tai 2010). While early childhood classrooms are not primarily focused on future career development, it is nonetheless important to note the increase in equity that may come from providing early experiences in science for children on a global level.

One of the most promising avenues for improving the quality of early childhood teaching is the use of inquiry and reflective practice to promote teachers’ professional growth (Abramson 2008; Castle 2012; Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2012; Stremmel 2012). The systematic use of reflection and inquiry at the preservice and in-service levels can improve teachers’ observational skills, instructional strategies, and capacity for self-reflection and can promote professional dialogue and collaboration.

Internationally, the most influential source of professional growth opportunities via inquiry and reflection—as inspiration, philosophy, and curriculum—is the Reggio Emilia early childhood educators in Italy (Rinaldi 2001; Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2012). Reggio has garnered international interest in its approach to a cohesive social and intellectual philosophy of teacher learning and development through inquiry, documentation, and collaboration. Documentation—the systematic collection and analysis of children’s ideas, language, and theories through various tools—lies at the heart of Reggio teachers’ inquiry and reflective practices.

The early childhood field at the global level, though, is in need of other international examples and approaches that educators can adapt to support teachers, children, and families in their specific local contexts. New Zealand, Finland, and other international contexts, for instance, offer their own approaches to inquiry and reflection that expand the possible global array of reflection models (Tobin, Hsueh, & Karasawa 2009; Kroll & Meier 2015). Recent work in the West Bank indicates that reflection is a promising approach for strengthening teacher inquiry for Palestinian teachers in early childhood (Wahbeh 2011; Khales & Meier 2013; Khales 2015) and elementary schools (Wahbeh 2011) through inquiry-based teaching.

In this article, we four authors describe and reflect on a cross-cultural and international exchange of data about inquiry-based teaching and learning in preschool-age children’s science engagement in the West Bank and in San Francisco. The project participants included a teacher educator working with several preservice and in-service preschool teachers in the West Bank/Palestine and a teacher educator working with two veteran preschool teachers in San Francisco.

Beginning our international project on science learning

The project began with four goals. First, all four authors sought new ways for the US teachers to serve as inquiry and curriculum mentors for the Palestinian teachers. Second, we wanted to develop new ideas and strategies for promoting inquiry-based science learning in varied educational, social, and cultural contexts. Third, we were interested in understanding how an international project on science learning might open new windows onto children’s social and cognitive development in cross-cultural contexts. Fourth, we hoped to begin filling a gap in existing research: while there is scant research on early childhood teacher inquiry at the whole-school level in the United States and internationally (Mardell et al. 2009; Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2012; Kroll & Meier 2017), there is even less information in the field of teacher inquiry about collaborative international projects. We framed this as an international project founded on teacher inquiry goals and strategies for closely observing children, documenting key moments and examples of science teaching and learning, and engaging in interpretation of data with colleagues (Meier & Henderson 2007; Castle 2012; Perry, Henderson, & Meier 2012; File et al. 2016).

Methodology

Given that this was the first collaborative international project for both teams, and that the US team could communicate only in English, both teams were unsure of how to frame the most fruitful initial research questions. The Palestinian team was interested in learning about child-centered, inquiry-based science teaching from the US preschool teachers, who in turn were interested in serving as mentors for the Palestinian teachers on teacher inquiry goals and tools. We four authors crafted broad initial questions that left enough curricular and inquiry space for us and the eight Palestinian teachers to proceed while maintaining the integrity of local teaching practices and of our respective cross-cultural interests:

- How can teacher inquiry help us understand new forms of effective science education for young children in two contrasting international contexts?

- How do both groups of international educators perceive and approach high-quality science education for young children?

- To what extent can an inquiry-based, cross-cultural exchange of classroom data influence teachers’ understanding of high-quality science education and the roles of teacher-directed and child-centered instruction?

The Palestinian team included one teacher educator (Khales, the second author), who teaches at a university in the West Bank and who has implemented innovative, inquiry-based teaching practices with preservice and in-service teachers. She worked with one preservice teacher and seven in-service preschool teachers from the Jerusalem (East) area, whose teaching experience ranged from 4 to 22 years.The teachers worked at a mix of public and private preschools, teaching classes of 20 to 30 children, ages 3 to 5, with Arabic as the primary language of instruction; they followed the centralized Palestinian Ministry of Education curriculum.

The San Francisco team consisted of one teacher educator (Meier, the third author) with extensive experience working with early childhood inquiry groups; one preschool teacher/director (Melgoza, the fourth author) with 25 years of experience, currently teaching in a private, play-based preschool for 3- to 5-year-olds; and one preschool teacher (Escamilla, the first author) with 20 years of experience, currently teaching in a Spanish-English public preschool with a project-based curriculum. All are experienced teacher inquirers.

The project took place over one academic year, with monthly exchanges of data and reflections by the US and Palestinian teams. Both teams designed science activities and projects at their sites. Using note taking, audiotaping, videotaping, photographs, and written reflections, they collected data on the children’s science interests and discoveries at least once a week.

The two teacher educators visited their respective sites once a month to observe the teachers’ strategies and the children’s science engagement; they took written notes and photographs and made brief video clips to document the most telling and instructive examples of teaching and learning. Each month, the teams uploaded selected data to the project’s private website for comment and feedback from group members. The data included photographs of children’s science play and work (such as a creation consisting of magnets) and written observations on the classroom science learning, in both contexts, from the four authors and the eight participating Palestinian teachers.

Data analysis

The two collaborative teams analyzed the project’s data with four primary interests that linked to the initial teacher inquiry questions:

- Children’s conversations and actions during their exploration of science activities and projects

- Teachers’ curricular planning, guidance and support of children’s learning, and written documentation and reflections on the teachers’ instructional practices

- Changes in the degree to which the respective teaching and research teams used more teacher-directed and/or child-centered teaching strategies as the project evolved

- The kinds of data uploaded to the private website, the comments made by project participants on the posted data, and the overall efficacy of using the website for data posting and reflection

The analysis relied primarily on narrative inquiry, a methodology that privileges narrative in data design, collection, analysis, representation, and dissemination (Lyons & LaBoskey 2002; Riessman 2008; Clandinin 2013). Narrative inquiry uses story to capture and understand telling moments, experiences, and perspectives and to help educators understand a particular educational puzzle. We relied on narrative inquiry to approach our project as a puzzle (Clandinin & Connelly 2000) and to examine how our science teaching and the children’s learning played out over two distinct social and educational spaces (Hatch & Wisniewski 2002; Ingold 2011). The two teacher educators involved in the project felt that narrative inquiry was helpful for keeping them engaged with the classroom realities that the Palestinian and US teachers faced (Souto-Manning & Ray 2007; Latta & Kim 2009, 2011).

The child-based data were examined for evidence of children’s science investigation; we analyzed their interests and curiosity (Ballenger 2009; Engel 2011), their conceptual understanding of big ideas in science (Sisk-Hilton 2013), and their use of peer-to-peer theory making and problem solving in science discovery (Gallas 1995). The teacher-based data were examined for evidence of curriculum design featuring elements of emergent teaching (Jones & Nimmo 1994) and the use of documentation for teacher reflection on teachers’ instructional practices and children’s science learning and discoveries (Mardell et al. 2009; Turner & Wilson 2010; Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 2012). We were especially interested in how our reflective tools might reaffirm teachers’ current instructional practices and expand their philosophies and understanding of inquiry-based science learning and teacher reflection. In reporting the project’s findings (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2012; Kroll & Meier 2015), elements of narrative inquiry are evident in the Palestinian and US teachers’ descriptions of key anecdotes and experiences as expressed in their own voices.

Findings and discussion

The project’s major findings are presented and discussed in two sections, one analyzed from the point of view of the Palestinian team and the other from the US team’s perspective. In each section, “we” is used to denote each respective international team.

Palestinian context: Fostering innovative instructional practices through inquiry and reflection

This international collaboration helped the Palestinian teachers design and implement science projects based on children’s interests and make the children’s learning more active and child centered. This is a new effort in Palestinian early childhood education. In the beginning, the teachers faced several challenges:

- How can we start the science projects?

- What are effective ways to coordinate with the US teachers?

- What data can we select and how can we write helpful reflections?

- How can we find the time to meet and discuss our data and reflections as a group?

A primary organizational feature that helped the teachers overcome these challenges was the reflective dialogue sessions that the Palestinian teacher educator facilitated with the group, which allowed them to brainstorm and develop new, inquiry-based approaches to teaching science and to documenting and reflecting on the children’s learning. As a result of this unusual new opportunity for in-service professional dialogue, we discovered as a group that we were indeed creative and found great professional value in focusing on effective pedagogy, which in turn strengthened our commitment to making changes to Palestinian science education.

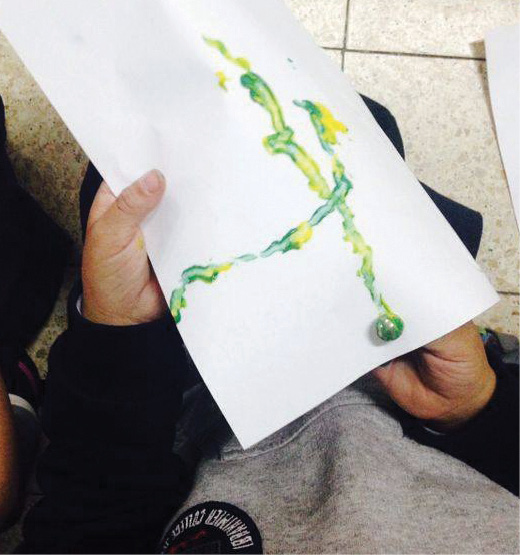

Palestinian child “painting” with a metal ball and a magnet as part of a more child-centered approach.

The teachers’ perspectives were gleaned from the inquiry group discussions, reflective postings to the project’s website, and their post-project reflections. Regular opportunities to meet and discuss our classroom science data, and to compare our teaching with our US counterparts’ teaching, helped the teachers realize that effective science education relies on a variety of hands-on, inquiry-based activities and projects that allow children to discover the world and teachers to support the processes by which children learn and understand information.

A new level of documentation, collaboration, and dialogue occurred via our data postings to the website and the exchange of ideas and practices with our US colleagues. Although we are experienced with posting to an electronic platform, sharing data with colleagues internationally was an entirely new process for us. It expanded the audience for our teaching and inquiry work, and in doing so stimulated a more intentional approach to data collection and analysis. The website allowed us to post and comment on our emerging science data and the emerging data from our US colleagues, both of which constituted a new professional opportunity for us to create and adapt more child-centered and discovery-based science activities. In turn, this new process of documentation and reflection encouraged us as teachers to ask children an expanded range of questions and to dialogue about their inquiries regarding certain science concepts and understanding.

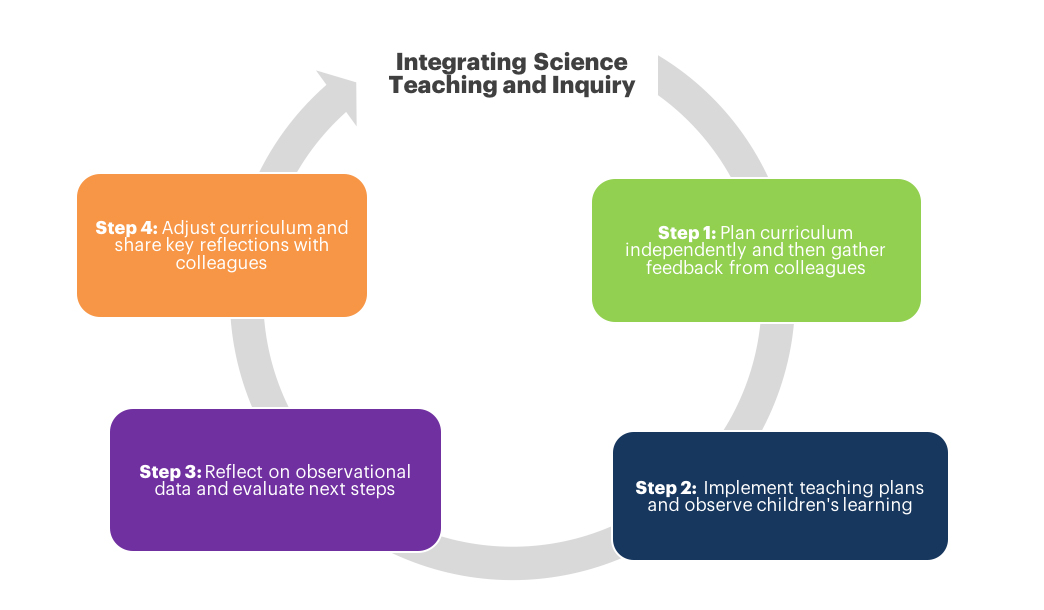

These critical elements are encapsulated in a model that integrates instructional practice and teacher inquiry, with an emphasis on Palestinian teachers implementing new approaches to child-centered, discovery-based science education. (See “Teaching and Reflection Cycle for Palestinian Preschool Science Education” below.)

Teaching and Reflection Cycle for Palestinian Preschool Science Education

In Palestinian early childhood education, we are working on a cycle (summarized in the figure below) that integrates teacher inquiry with curriculum changes. We implemented this cycle at the teachers’ various sites in this project to improve our science teaching and strengthen a sense of professionalism. First, teachers plan curriculum independently according to their particular children’s interests and then engage in dialogue with colleagues through face-to-face meetings and sharing their plans on the private website for feedback and ideas for improvement. Second, the teachers implement their plans and observe the children’s learning. Third, the teachers reflect on their observational data and evaluate possible new directions for improved instruction. Fourth, the teachers make instructional adjustments, evaluate the effectiveness of the changes, and then share their most valuable results with colleagues on the private website.

After reading descriptions of the US children’s science learning and the US teachers’ reflections, we compiled our own critical questions on curriculum and teaching:

- How did the US teachers implement these play-based activities with these young learners?

- Where did they get these activities? Did they refer to a resource book or create the activities on their own?

- Did all the children engage in these activities with interest and enthusiasm?

- If not, what additional procedures did the teachers initiate?

These kinds of questions indicated an increased level of engagement with curriculum planning and instructional strategies for us as Palestinian teachers. This was of particular importance, given that Palestinian teachers are in the early stages of conceptualizing and implementing more child-centered approaches.

Our exchanges with the US teachers also promoted a new realization for us that we can create new ideas for effective science curriculum and reflective practice to share with other educators and communities. As our data, anecdotes, and reflections reveal, the cross-national nature of the project encouraged us to take new risks, try new teaching activities and experiences, and exchange ideas and projects without feeling any inferiority or threat. In short, we were encouraged to reflect on a more enjoyable way of teaching and to develop ourselves more fully as early childhood professionals.

The regular meetings among ourselves, and the regular web postings and comments with our US colleagues, helped us become more familiar with the concept of reflection and the use of inquiry strategies, including close classroom observations, note taking, photographs, videotaping, written reflections, and conversation and collaboration with colleagues. This new process of integrating reflection with teaching practices also encouraged us to face certain challenges and difficulties in our science teaching. For instance, after reading written observations and reflections on lessons from the US teachers, we looked for alternative ways to create more open-ended and inquiry-based teaching.

The use of videos was a particularly valuable element in our introduction to ideas and practices for inquiry and reflection. Some of us made videos of the children’s science learning and then showed them to our colleagues for feedback, others made videos for self-assessment and self-improvement, and some teachers exchanged videos to get additional feedback and dialogue. Initially, several of us were reluctant to present our activities to others, hesitant to show weaknesses or seek ideas through collective reflection. The collaborative nature of our team and the supportive feedback from the US teachers helped us gain confidence and skill in presenting data and reflections.

Razan, a preservice teacher, was eager to implement science strategies that she had learned in her university classes (taught by the second author, Khales) that promoted children’s discovery and curiosity. She also wanted to observe and understand the value of a playful approach to science engagement for young children, and decided on a play scenario involving a mischievous cat that she hoped would spark the children’s interest in magnets and their properties. (See “Data Anecdote: Razan Playfully Scaffolds a Magnet Scenario” below.)

Data Anecdote: Razan Playfully Scaffolds a Magnet Scenario

Before the children arrived, I put the iron filings on the classroom floor and I painted small cat feet on paper near the filings. I also put out nails, metal pins, plastic parts, and an iron ruler. When the children entered the classroom, I told them that before they arrived, a cat had come and caused chaos with the materials (I did not call them iron filings), and we needed to clean the mess without directly using our hands.

I asked the children if they knew the composition of the material on the floor. Some said “iron” and “iron filings.” I asked them how they could remove the iron filings and the metal pins without using their hands. One child said “a magnet.” I then put out some materials that are attracted by magnets (metal pins and screws) and other materials not attracted by magnets (wood, plastic, and cork). I distributed magnets to the children and asked them to classify the materials by those attracted by the magnets and those that were not. The children began to eagerly test the objects with the magnets, and they discussed their discoveries with each other as they arose.

Iron filings for experimentation in Razan’s classroom.

Reflection

As a preservice teacher in my fourth year as a BA student in early childhood education, I tried to provide a playful initial provocation (the cat has caused chaos with the materials) and to pose a problem for the small group of children to solve (how to clean up the materials without using their hands). I wanted to implement a hands-on, playful activity that would engage the children in problem solving and discovery. As I have learned in my preservice early childhood coursework, I also wanted the activity to support certain scientific, linguistic, and social benefits that promote inquiry-based science learning for young children:

- Explore objects, materials, and events

- Raise questions

- Observe

- Engage in simple investigations

- Describe (including shape, size, number), compare, sort, classify, and order

- Use a variety of simple tools to extend observations

- Identify patterns and relationships

- Develop tentative explanations and ideas

- Work collaboratively with others

- Share and discuss ideas and listen to new perspectives

It was valuable to teach a project like magnets that doesn’t exist in our textbook. The science activities helped the children to discover knowledge on their own; they also engaged in higher stages in the educational process of learning and discovering. I saw this in their reactions, for instance, when they were experimenting with the iron filings and magnets. They made important discoveries about the properties of magnets. This project offered the students something out of the ordinary and unleashed their thinking from the more teacher-directed daily routine.

Toward inquiry-based science teaching and teacher reflection

The teachers reported a new understanding of the intricacies and the value of inquiry-based science teaching, and also a new appreciation for reflection in collaboration with local and international colleagues. The following two reflections are from teachers with 8 and 22 years of experience, respectively.

Tahani’s Reflections: The Benefits of Facing a Challenge

It was very impressive for the children to identify properties of the magnets, and it was enjoyable for the children to engage in experiments to gain knowledge about magnets. The activities also increased the children’s confidence and their abilities as they discovered which objects the magnets attract and which do not. In the process, the children learned to face a challenge, control the activity, and turn their learning into an achievement. In one challenging problem, the children made discoveries about the extraction of iron from the sand with the magnets. These kinds of more open-ended and playful science experiences also increased the children’s language to express what they were learning and discovering.

Iman’s Reflections: Understanding Inquiry in Practice

This was a new kind of project that included new kinds of child-centered science activities, and allowed us the opportunity to convey and transfer our expertise to each other here in Jerusalem and with our San Francisco colleagues. It helped us observe each other’s teaching of new science topics, and to find new ways to discuss how children learn science in effective ways. It was helpful professionally for us to share our experiences and voices, and to hear others’ suggestions about how to encourage children’s emotional development, cognition, and social interaction through science. Teachers understand the meaning of inquiry in practical ways: when we discussed our data and reflections with the US teachers, this new process helped us understand what inquiry means in practice and implementation. At the beginning of the project, we knew the word inquiry but did not understand its practical and professional value for our teaching and for the children’s learning.

US context: Promoting reflection on science through international collaboration

The following anecdote and reflection capture one way this project deepened our understanding of inquiry and science learning through the lens of international professional collaboration.

Data Anecdote: Martha Benefits from Mirroring Others’ Practices

The sharing of documentation between the teachers in two countries with two languages proved challenging, and at the project’s close, I was left with the desire to ask questions and find out more direct information from the teachers. Yet this cross-national experience still provided a new view for me to look at educational practices across the globe. Through the Palestinian teachers’ documentation, I learned about Palestinian class size, cultural expectations within the classroom, use of science resources in the classroom, and teacher project planning. Although the lack of direct face-to-face communication prevented a deeper exchange of ideas, the shared framework of teacher reflection allowed me to explore and expand my understanding of my own practice. It provided me the time to look deeper into my practices and ask myself questions as to how and why I teach and work with my own teaching staff in the way I do.

Our shared project on magnets helped me reexamine my long-standing interest in emergent curriculum based on children’s interests (Jones & Nimmo 1994). The Palestinian educators thought of presenting a magnet theme in their classrooms and suggested that the US team consider introducing the topic in our classrooms as well. Magnets had not been something my students or I had on our list of interests at that particular time. Since we follow an emergent curriculum, it felt a little strange to introduce what felt like a random topic. Yet, over many weeks, I put out a range of magnets and magnetic materials for free exploration and discovery.

Magnets for outdoor experimentation in Martha’s classroom.

Magna-Tiles and cars creation in Martha’s classroom.

I provided different magnet activities for the children to explore at their own pace. There were no directions, nor a teacher or parent assigned to the space to explain the magnetic properties. At one point, I sat down to interact with the children. The metal shavings activity did not hold the children’s attention for very long. The magnetic base with the circle magnets drew in a group of children and sustained their attention for 15 minutes. Some worked at stacking the circles either randomly or sorting by color. They discovered that sometimes the magnets repel and do not stack. I asked them why, and they responded:

- “They are not the same color.”

- “They are hoovering” [repelling].

- “They need to be weighed down to stay.” [The children tried many times to weight them down.]

- “They are bouncing.” [As the children tried to force the magnets together, they discovered that the magnets bounced away from one another and that some even flew off the table.]

The group continued testing their ideas. By adding more magnetic circles to the vertical wooden stick, the children weighted down the magnets and reduced the possibility of the “hoovering” space, or the magnets repelling each other.

Reflection

The manner in which I participated in this activity was unusual. Normally, I am not such an active participant in conversations with young children. I usually let children explore materials for at least one day before I sit with them. When I eventually sit with them, I start by observing and discovering what they already know about the materials. This allows me to formulate questions and appropriate scaffolding and give the children more space to think about the activity.

In rereading my journal entries and reflecting on the magnet activities, I was pleased to note that the children described and named “hoovering” and “sticking” as important magnetic properties. The children asked questions and came up with possible explanations and reasons for what was occurring and shared their knowledge with one another. It sounded like everything I plan and hope for. Yet, the experience at the time felt false to me somehow. On reflection, I realized that I gave the activities less initial thought than I usually do, and the children were not following the magnets as an emergent interest. They were learning about the magnets’ properties but had other reasons for their sustained focus and involvement with the activities. For instance, the children enjoyed the Magna-Tiles for the materials’ building capabilities; the fact that they are magnetically held together did not seem to consciously interest the children.

If it were not for our decision to follow the Palestinian teachers’ science topic suggestion, I would have dropped the exploration of magnets, considering exposure to magnets as valid in the early childhood classroom. This sharing of classroom experiences with the Palestinian educators provided me with the opportunity to take a deeper look at my practices. It allowed me to question the how and why of presenting curriculum at my school. As a site director who also works with the children as a teacher, it also helped me understand the value of more direct conversation techniques and involvement with the children’s thoughts and actions, especially when presenting an activity with no planned connection to an emergent theme or focus. This experience also inspired me to engage in more professional and collaborative ventures like this to help keep my practice alive.

Data Anecdote: Isauro Develops a New Perspective on a Pedagogy of Listening

When I proposed to my coteachers that we start a new study on magnets, they did not immediately embrace the idea, since we were in the middle of a long-term project investigating and documenting the children’s water play. The idea of documenting the children’s magnet play was suggested by our Palestinian counterparts, and so we decided to switch our focus so we could carry out a parallel curriculum with the Palestinian team.

Magnet construction in Isauro's classroom.

One of the first data posts came from Razan in Jerusalem, who offered her children a pound of magnetic filings to explore, while she facilitated the activity. In her posting, she reflected on a two-minute video that she had taken of the children’s explorations. From the outset of our project, I noticed how the Palestinian teachers felt at ease filming the children’s science engagement and then discussing what they observed on the videos. I also noticed how the Palestinian teachers, in the magnet project, for instance, used more direct teaching and scaffolding with the children. In accordance with our project-based philosophy, my coteachers and I presented a variety of magnetic materials and let the children explore and use them in their play on their own terms. We were more interested initially in facilitating play and exploration than having the children discover specific scientific properties of magnets.

Magna-Tile creation in Isauro’s classroom

We shot five videos of the children’s magnet engagement, and I described and reflected on two short videos on our project’s private website. In one video clip, two children play with magnetic tiles to make designs using different tile shapes. One makes a circle using triangle tiles; when her circle is complete, she places small animals on each one of the triangles. Then, she counts the number of tiles she used to complete her circle. At the same time, the other child makes several little houses, using two squares and three triangles for each one of the structures. She was making triangular prisms. In a second video, two different children make a tall structure with magnetic rods and spheres that they describe as a castle. As they work together to build their castle, they talk to each other in Spanish, exchanging ideas and taking turns adding one piece at a time to make the structure strong.

Experimenting with Magna-Tiles outside Isauro’s classroom

Reflection

In these two video clips, I engaged in the following inquiry and reflection actions: listening, observing, writing, photographing, filming, and thinking. The use of our project’s private web page, and the Palestinian teachers’ affinity for using brief video clips to understand their children’s science engagement, prompted me to take more short videos and to engage in a new reflection and documentation process using video. In general in my reflection work, I organize my ideas, photos, notes, and images so that I can start giving them form and make sense of an event. It is at this point that a story starts to slowly emerge and gain meaning. The new strategy of collecting and analyzing brief video clips deepened my interpretation of my notes, photos, and ideas. For example, when I reviewed the video of the castle building, I noticed and reflected on several aspects of the children’s magnet engagement:

- They took special care placing the magnetic rods on the corners to create a solid frame

- The spheres they used to connect the rods offer the possibility to add new words to their math and science vocabulary, such corners and angles

- These activities were spontaneous and created by the children themselves with materials easily available in the classroom

- The initial photographs and videos of children using magnetic materials might give us ideas for other teacher-guided magnet activities in the near future

In general, the posting of our reflections on our project’s website proved a convenient and flexible way for sharing and commenting on data in two distant international contexts.

I was humbled to see the openness with which the Palestinian teachers shared their ideas, and I admired their willingness to break the barriers of distance, time, and language to exchange ideas about how to connect with teachers in another part of the world. The Palestinian teachers used more teacher-directed strategies with more specific pedagogical and conceptual goals than our play- and project-based curriculum. I also learned from them how teachers can engage an entire class of preschool children in science activities, as compared with our emphasis on small group work. Over time, and perhaps in response to our teaching, the Palestinian teachers became more inclined to work in small groups to demonstrate a science activity or material as an effective approach for modeling for the entire class’s subsequent participation.

Conclusion

This project offers new conceptual and pedagogical windows into how teachers and teacher educators in contrasting international settings can link high-quality science curriculum with teacher inquiry in a way that becomes responsive to local and international beliefs, goals, practices, environments, and materials. In this closing section, Palestinian educators, US educators, and the international group as a whole reflect on a few key highlights from our project.

First, the project became a reflexive process (Bold 2012) of learning and inquiry for the teachers and teacher educators. The implementation of inquiry groups and professional discourse allowed us to hold up a mirror to reflect on both local and international science teaching beliefs, practices, methods, and environments. The mirroring occurred locally for the Palestinian and US educators as members of each team compared their evolving data with the data of their fellow members. It also occurred internationally as the two research teams shared and compared selected data and reflections across borders. For example, the use of a private website for posting reflections afforded each team a central site to view their own postings and those of the other international team.

Second, the Palestinian educators now have a better understanding of the value of small group and discovery-based science education. They now recognize the value of giving more time to a set of activities, thinking carefully about asking many different kinds of questions, and letting children ask their own questions of teachers and peers. For example, the Palestinian children were offered many new objects to discover the properties of magnets, and they responded to this learning opportunity with their own meaningful questions.

Similarly, the US educators now understand how to incorporate some elements of direct teacher support that they saw in the Palestinian teachers’ work and how to offer more structured opportunities for science investigation that touches on science concepts and information (instead of simply science as a set of exploratory processes). For instance, the Palestinian teachers’ efforts to help children learn certain properties of magnets helped the US teachers question the limits of play-based curriculum. They learned to recognize certain potential blind spots in their perspective and knowledge base on child development and professional growth, which privilege only certain forms of teaching and learning (Ebrahim 2012).

Third, the linking of science education with teacher inquiry proved valuable for both international teams. The Palestinian educators learned to adapt ideas and practices about inquiry and reflection, including using inquiry tools for observation, analysis, and representation. They are at the beginning stage of integrating teacher inquiry into their science teaching while trying to make curricular changes to Palestinian early childhood science education. This will take time to implement in a meaningful and lasting way. The US educators, as veteran inquirers, now realize how much they can learn from international colleagues who are new to teacher inquiry; the US team found it challenging to return to the fundamentals of inquiry work. For example, at the outset of the project, they considered themselves experts in inquiry and were eager to serve as inquiry mentors for the Palestinian teachers. Halfway through the project, they realized they had a great deal to learn from their Palestinian colleagues; for instance, the novel use of taking brief videos of children learning science and posting teachers’ reflections on a shared website were approaches worth pursuing.

Implications

The project has three major implications for other early childhood teachers and teacher educators interested in transforming science education via inquiry-based collaboration.

First, for educators interested in deepening their knowledge of high-quality science education, we suggest exploring dialogue and sharing teaching beliefs and practices with early childhood educators internationally. The process of focusing on a single curricular area (such as science) and the same topics (such as magnets) provides a welcome and refreshing perspective on one’s teaching goals and strategies. Such an exchange, as in our project, can provide new motivation and information for veteran teachers to question and deepen their teaching. For new teachers, the opportunity to dialogue with veteran teachers, both locally and internationally, offers a valuable stepping stone toward improving their professional practice.

Second, exchanges can be strengthened by integrating a range of inquiry-based strategies, from photographs to videos to written reflections to an electronic platform. The opportunity to choose from a wide range of inquiry tools at the outset helps teachers with varied levels of inquiry experience select tools that they feel comfortable with and provides an expanding toolbox of strategies. We also recommend further exploration of electronic platforms. For the Palestinian team, the use of a private website was a familiar and effective platform, but they had not previously used it as a tool for systematic teacher reflection. The US team was entirely new to the platform and at times found it problematic. For instance, the default translation of written text from Arabic to English was poor, and the nuances of intent and reflection in the original Arabic were lost. We now recommend the addition of other more direct forms of electronic communication (such as Skype or Google Hangout) for international dialogue.

Last, we recommend the inclusion of teacher educators in international inquiry-based collaboration, as in this project’s Palestinian teacher educator and the US teacher educator, who were co-organizers and who helped guide the initial inquiry framework, tools, and reflections. Local teacher educators are familiar with curricular knowledge at the preservice and in-service levels and can pinpoint places in international exchanges where inquiry and reflection can work in tandem to strengthen data exchanges and interpretation. To further improve the role of the two teacher educators in this project, we now see the value of more long-term collaboration. Both teams look forward to new possibilities for improving international exchanges.

References

Abramson, S. 2008. “Co-Inquiry: Documentation, Communication, Action.” Voices of Practitioners. www.naeyc.org/files/naeyc/file/vop/Voices_Abramson_Co-Inquiry.pdf.

Ballenger, C. 2009. Puzzling Moments, Teachable Moments: Practicing Teacher Research in Urban Classrooms. New York: Teachers College Press.

Bold, C. 2012. Using Narrative in Research. New York: Sage.

Bradley, B.A. 2016. “Integrating the Curriculum to Engage and Challenge Children.” Young Children 71 (3): 8–16.

Castle, K. 2012. Early Childhood Teacher Research: From Questions to Results. New York: Routledge.

Clandinin, D.J. 2013. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Clandinin, D.J., & F.M. Connelly. 2000. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ebrahim, H. 2012. “Tensions in Incorporating Global Childhood with Early Childhood Programs: The Case of South Africa.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 37 (3): 80–86.

Edwards, C., L. Gandini, & G. Forman, eds. 2012. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. 3rd ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Engel, S. 2011. “Children’s Need to Know: Curiosity in Schools.” Harvard Educational Review 81 (4): 625–45.

Evans, L.M., & A. Avila. 2016. “Enhancing Science Learning through Dynamic Bilingual Practices.” Childhood Education 92 (4): 290–97.

File, N., J.J. Mueller, D.B. Wisneski, & A.J. Stremmel. 2016. Understanding Research in Early Childhood Education: Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. New York: Routledge.

Gallas, K. 1995. Talking Their Way into Science: Hearing Children’s Questions and Theories, Responding with Curricula. Language and Literacy series. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gelman, R., & K. Brenneman. 2004. “Science Learning Pathways for Young Children.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 19: 150–58.

Gort, M., & S.F. Sembiante. 2015. “Navigating Hybridized Language Learning Spaces through Translanguaging Pedagogy: Dual Language Preschool Teachers’ Languaging Practices in Support of Emergent Bilingual Children’s Performance of Academic Discourse.” International Multilingual Research Journal 9 (1): 7–25.

Hatch, J.A., & R. Wisniewski, eds. 2002. Life History and Narrative. Qualitative Studies series. New York: Routledge.

Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description. New York: Routledge.

Jones, E., & J. Nimmo. 1994. Emergent Curriculum. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Khales, B. 2015. “Reflection through Story: Strengthening Palestinian Early Childhood Education.” Chap. 11 in Educational Change in International Early Childhood Contexts: Crossing Borders of Reflection, eds. L.R. Kroll & D.R. Meier, 174–87. New York: Routledge.

Khales, B., & D. Meier. 2013. “Toward a New Way of Learning: Promoting Inquiry and Reflection in Palestinian Early Childhood Teacher Education.” The New Educator 9 (4): 287–303.

Kroll, L.R., & D.R. Meier, eds. 2015. Educational Change in International Early Childhood Contexts: Crossing Borders of Reflection. New York: Routledge.

Kroll, L.R., & D.R. Meier. 2017. Documentation and Inquiry in the Early Childhood Classroom: Research Stories from Urban Centers and Schools. New York: Routledge.

Latta, M.M., & J.-H. Kim. 2009. “Narrative Inquiry Invites Professional Development: Educators Claim the Creative Space of Praxis.” Journal of Educational Research 103 (2): 137–48.

Latta, M.M., & J.-H. Kim. 2011. “Investing in the Curricular Lives of Educators: Narrative Inquiry as Pedagogical Medium.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 43 (5): 679–95.

Lyons, N., & V.K. LaBoskey, eds. 2002. Narrative Inquiry in Practice: Advancing the Knowledge of Teaching. Practitioner Inquiry series. New York: Teachers College Press.

Maltese, A.V., & R.H. Tai. 2010. “Eyeballs in the Fridge: Sources of Early Interest in Science.” International Journal of Science Education 32 (5): 669–85.

Mardell, B., D. LeeKeenan, H. Given, D. Robinson, B. Merino, & Y. Liu-Constant. 2009. “Zooms: Promoting Schoolwide Inquiry and Improving Practice.” Voices of Practitioners 11 4 (1): 1–15. www.naeyc.org/files/naeyc/file/vop/Voices_Zooms.pdf.

Meier, D.R., & B. Henderson. 2007. Learning from Young Children in the Classroom: The Art and Science of Teacher Research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Meier, D.R., & S. Sisk-Hilton, eds. 2013. Nature Education with Young Children: Integrating Inquiry and Practice. New York: Routledge.

Metz, K.E. 2008. “Narrowing the Gulf between the Practices of Science and the Elementary School Science Classroom.” Elementary School Journal 109 (2): 138–61.

Moje, E.B., T. Collazo, R. Carrillo, & R.W. Marx. 2001. “‘Maestro, What Is Quality?’: Language, Literacy, and Discourse in Project‐Based Science.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 38 (4): 469–98.

Parnell, W., C. Downs, & J. Cullen. 2017. “Fostering Intelligent Moderation in the Next Generation: Insights from Remida-Inspired Reuse Materials Education.” The New Educator 13 (3): 234–50.

Perry, G., B. Henderson, & D.R. Meier, eds. 2012. Our Inquiry, Our Practice: Undertaking, Supporting, and Learning from Early Childhood Teacher Research(ers). Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Riessman, C.K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rinaldi, C. 2001. “The Pedagogy of Listening: The Listening Perspective from Reggio Emilia.” Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Exchange 8 (4):1–4.

Sisk-Hilton, S. 2013. “Science, Nature, and Inquiry-Based Learning in Early Childhood Education.” Chap. 1 in Nature Education with Young Children: Integrating Inquiry and Practice, eds. D.R. Meier & S. Sisk-Hilton, 9–25. New York: Routledge.

Souto-Manning, M., & N. Ray. 2007. “Beyond Survival in the Ivory Tower: Black and Brown Women’s Living Narratives.” Equity and Excellence in Education 40 (4): 280–90.

Stremmel, A.J. 2012. “Reshaping the Landscape of Early Childhood Teaching through Teacher Research.” Chap. 9 in Our Inquiry, Our Practice: Undertaking, Supporting, and Learning from Early Childhood Teacher Research(ers), eds. G. Perry, B. Henderson, & D.R. Meier, 107–16. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Taylor, A.F., & F.E. Kuo. 2006. “Is Contact with Nature Important for Healthy Child Development? State of the Evidence.” Chap. 8 in Children and Their Environments: Learning, Using, and Designing Spaces, eds. C. Spencer & M. Blades, 124–40. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Tobin, J., Y. Hsueh, & M. Karasawa. 2009. Preschool in Three Cultures Revisited: China, Japan, and the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Turner, T., & D.G. Wilson. 2010. “Reflections on Documentation: A Discussion with Thought Leaders from Reggio Emilia.” Theory into Practice 49 (1): 5–13.

Wahbeh, N. 2011. “Early Childhood Education in Palestine: An Evaluative Study of a Three-Year Professional Development Program.” Unpublished research report. Ramallah, West Bank: A.M. Qattan Center for Educational Research and Development.

White, R. 2006. “Young Children’s Relationship with Nature: Its Importance to Children’s Development and the Earth’s Future.” Taproot 16 (2).

Williams-Siegfredsen, J. 2012. Understanding the Danish Forest School Approach: Early Years Education in Practice. New York: Routledge.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to learn more about teacher research and peruse an archive of Voices articles.

Isauro M. Escamilla, MA, is an early childhood educator at the San Francisco Unified School District and a lecturer at San Francisco State University. [email protected]

Buad Khales, PhD, is assistant professor of curriculum and instruction and early childhood education at Al-Quds University, Jerusalem, Palestine. Her research focuses on child-centered teaching, inquiry, and new curriculum models for Palestinian early childhood education. [email protected]

Daniel R. Meier, PhD, is professor of elementary education at San Francisco State University. His publications include Critical Issues in Infant-Toddler Language Development: Connecting Theory to Practice (editor), Supporting Literacies for Children of Color: A Strength-Based Approach to Preschool Literacy (author), and Learning Stories and Teacher Inquiry Groups: Reimagining Teaching and Assessment in Early Childhood Education (coauthor).

Martha Melgoza is a director at Skytown Preschool in Richmond, CA. She encourages educators from the K–20+ system in the US, as well as globally, to reach out to her and join forces to define new inquiry and research projects. Her main interests revolve around teacher collaboration with families, reframing early childhood to better see the child through a lens of respect, bridging the transition for children and families into kindergarten with more ease and humanity, and other topics that deeply affect educators. Please reach out at [email protected].