Real-Life Reasons to Write

You are here

I am sure many of us remember sitting at a desk and writing the same alphabet letter over and over again, several times tracing a dotted line, and then finally on our own. But why were we writing that letter? What did it mean? More important, if we had asked our teachers these questions, what would they have said?

As a young preschool teacher, those memories are fresh in my mind, so I make sure every writing experience in my classroom is meaningful for children and has an authentic purpose. Such opportunities help children become skilled and enthusiastic writers.

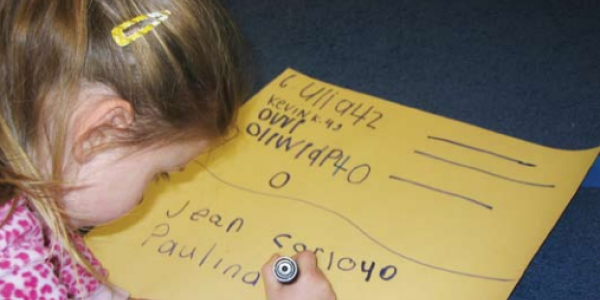

Each child has his or her own unique method when beginning to write. To respect the styles and skill levels of all of the children, I provide a range of writing activities. Here are some ways we give the children in our classroom real-life opportunities to write.

Attendance. Children sign in when arriving at school, just as they see grown-ups do. They use a pencil tied to a string next to the sign-in sheet, posted within their reach.

List making. When we make a plan for a class party or activity, we let the children write or dictate a list of what we need. As we receive the items, the children check them off the list.

Notes and cards. Children regularly make greeting cards for birthdays, holidays, and other occasions, for families, friends, classmates, and teachers. They write thank-you notes to guest speakers and to family members who read to the class, participate on field trips, or take part in other classroom activities. I introduce thank-you notes at the beginning of the year, and soon children are writing them on their own.

Letters that express feelings. When children have a disagreement, I encourage them each to write a letter to the other person, explaining their thoughts and feelings. Sometimes, if a child is having a bad day, I read Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, and then I suggest that the child draw a picture and sign it, like Alexander does in the story.

Notes home. When writing to ask a child’s family for a change of clothes or to tell them about the amazing block structure their child made, I invite the child to help me. I might write a question like, “Can you please send in . . . ?” and then use a think-aloud strategy, for example, pointing out that “I need to use a question mark here because I asked a question.” In this way the child sees how punctuation helps make my message clear.

Journal writing. Children write and draw about their favorite parts of the day. They may record things they want to remember or jot down words from the word wall. We post photos with captions that include words pertaining to our current studies. The children refer to the captions when trying to remember the name of a particular object or living creature, which helps build their vocabularies. Eventually they remember the new words on their own and no longer need to refer to the photos.

Fine motor skill development. A variety of materials and activity choices let children practice their small muscle skills. For example, children make 3-D letters and words using playdough. They squirt glue in the shape of a letter and shake sand or glitter on top to create letter cards. Later, they can trace the shape of the letter with their fingers. At group time I invite the children to use their bodies to form letters.

Waiting lists. Children are always eager to enter certain interest areas, and they tend to get upset when the area is full. A waiting list works well as a visual prompt for taking turns. It also removes me from the action! Children write their name next to a number on the list. When a classmate leaves the area, she lets the next child know it’s his turn. Before entering the area, he places a check mark next to his name, indicating that he is taking his turn in the area.

Monthly newsletter. Every month each child chooses a topic to write about, and all of the contributions are included in the newsletter. Some children write about the topics we are studying, others describe recent activities, birthday celebrations, or the weather. In some cases, children ask to take a digital photo of a block building or art project to include with a written caption. They help to print the photos using the computer. We work on the newspaper over several weeks before sending it home as a “month in review,” such as “October in Review.” The more involved the children are in each step of the process, the more excited and motivated they are to write and learn.

Children’s literature. I read several books by the same author to highlight how writers develop their themes and styles over time and how they repeat favorites or try out new ones. Sometimes we write alternate versions of stories we read during group times. We also make story maps on large pieces of paper to clearly separate the story into the beginning, the middle, and the end. This helps the children see the sequence of events unfold on one sheet of paper. To the story map they can add their own artwork, dictation, and shared writing with the teacher, using vocabulary words and characters from the story.

Supporting Dual language learners

The terms meaningful and with authentic purpose are key to successfully supporting dual language learners. Boring, repetitive, artificial tasks are not worth much, no matter the language. On the other hand, authentic activities that really connect to a child’s prior knowledge and home experiences make activities much more effective for all learners. It is worth the extra effort to provide writing models and activities in the home languages of the children. Be sure to focus on real-life examples and things children really want to write about! Research tells us that early literacy skills learned in the home language are likely to transfer easily to English later on, so home language writing activities support success in later grades.