Collaborative Conversations: Speaking and Listening in the Primary Grades

You are here

Supporting meaningful conversations among young children can be challenging but is well worth the effort. Many studies have demonstrated the importance of developing speaking and listening skills in early childhood (Hall 1987; Clay 1991; Kirkland & Patterson 2005). As part of a collaborative study, we—a firstgrade teacher and two university-based researchers—set a goal to facilitate meaningful, student-led discussions about literature. We began by having students bring books to whole- and small-group activities and encouraging them to talk. While this was a good start, we quickly realized that the children needed support to learn how to interact appropriately during conversations that were not led by the teacher. Figuring out what types of supports would be effective became the heart of our study.

In this article we share several strategies that we found successful in enhancing the speaking and listening skills of a class of 28 first graders. The children— who came from diverse linguistic, economic, and social backgrounds—began the school year with below average to average literacy skills. Meridith, the teacher (and second author), had 12 years of teaching experience; throughout the yearlong study, she acted as both a researcher and a participant, trying out and reflecting on each of our instructional ideas.

We wanted to help the children develop the ability to have meaningful conversations about books without needing Meridith’s guidance. Our goal was for the children to collaboratively construct interpretations of texts through group discussions. Discussion increases students’ engagement, helps them take responsibility for their learning, prompts higher-level thinking, offers room for clarification, encourages children to build and share knowledge, and gives them opportunities to apply comprehension strategies (Kelley & Clausen- Grace 2013). We aimed to create an environment where children could scaffold each other’s learning (Johnston 2004) through talk. Knowing that research has demonstrated that discussion supports comprehension (Wells 1999; Nystrand 2006), we set out to teach young children to engage in such exchanges.

Discussion also offers the benefit of being inclusive of students from diverse backgrounds. Previous work has found that discussion increases participation for dual language learners and reading enjoyment for all (Carrison & Ernst-Slavit 2005), and that conversations enable teachers to publicly value all students’ thinking and talk.

However, powerful literary discussions do not emerge naturally in the primary grades. Research and our experiences have identified the need for teacher support (Baker, Dreher, & Guthrie 2000) through methods such as explicitly teaching children the social skills necessary for conversation (Harvey & Daniels 2015), teaching students to talk to each other without relying on the teacher (Serafini 2009), and providing time for children to prepare and reflect (Kelley & Clausen-Grace 2013).

In addition to the academic, social, and motivational benefits of literature discussions, the Common Core State Standards (NGA & CCSSO 2010) reinforce the importance of teachers devoting time to enhancing children’s speaking and listening skills. Speaking and listening standards are part of the Common Core Language Arts Standards for each grade. Through our study, we expected to address the following standards, which focus on collaborative talk, following discussion norms, adding to the contributions of others, and asking questions:

- SL.1.1: Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about grade 1 topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups.

- SL.1.1.A: Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to others with care, speaking one at a time about the topics and texts under discussion).

- SL.1.1.B: Build on others’ talk in conversations by responding to the comments of others through multiple exchanges.

- SL.1.1.C: Ask questions to clear up any confusion about the topics and texts under discussion.

Fostering student-led discussions

From the beginning of the year, Meridith taught speaking and listening in academic contexts. She supported children in listening to and learning from each other, preparing for discussions, and taking responsibility for discussions.

Teacher support for speaking and listening

Meridith provided explicit instruction in speaking and listening. First, she focused on teaching students to listen. She offered explanations, modeled appropriate behaviors, and gave children time to practice sitting up, resisting distractions, and looking at the speaker. When students struggled to stay focused, she gently encouraged the speaker to pause until all the students were looking. In the following transcript from a fall classroom observation, Meridith provided explicit instruction about how to listen during whole-group discussions:

Meridith also offered more subtle speaking and listening support by calling attention to conversational norms—like saying, “I hear Jorge talking,” when another student was about to interrupt—and using nonverbal cues, like eye contact and pointing, to remind children of expectations.

Meridith’s reflection

At the start of every year, I envision students independently engaging in meaningful discussions while I take notes and think about how these grand conversations will guide my instruction. Then I remember it is August and they are six. Starting with basics—such as body language, conversational turns, and voice projection—helps set the tone for future discourse. While it seems simple, and we often assume children have already internalized these skills, many have not. Investing time in explicitly teaching basic conversation skills allows children to be more independent and go deeper with their thoughts.

Children’s responsibilities in discussions

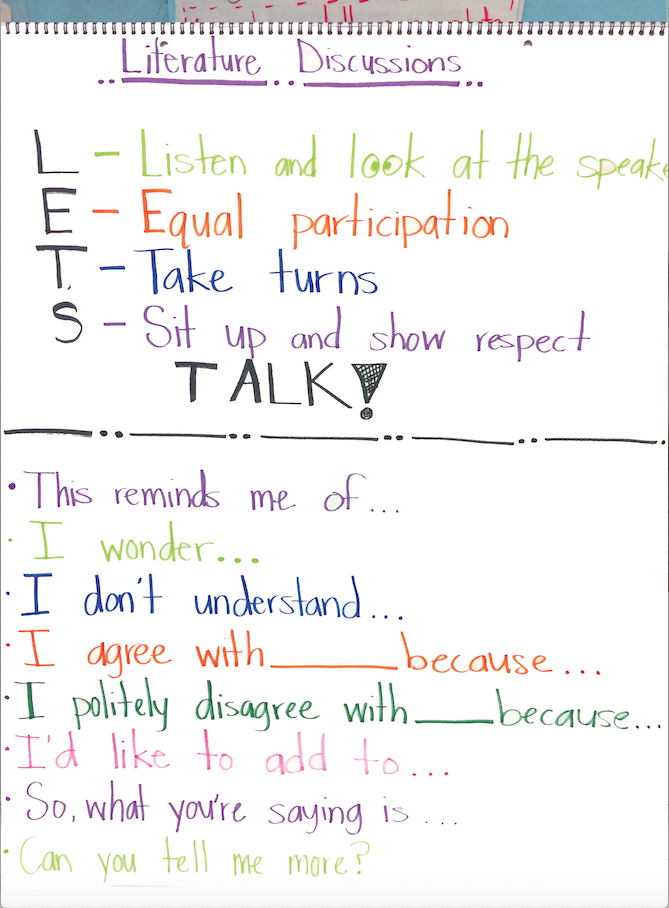

Meridith taught students to take ownership of discussion norms. She expected children to wait until there was silence and eye contact from everyone before they started to talk. If children began speaking before listeners were ready, she would remind them to get the attention of the audience. For example, she taught them to use a cue—saying, “Class, class,” and waiting for the other students to respond, “Yes, yes?”—before continuing the discussion (Biffle 2013). She had students take responsibility for calling on each other, including recognizing who still needed to participate in the conversation. Meridith also taught them the language frame “Questions, comments, or connections?” to generate discussion and responses. (For additional language frames that supported discussion, see the photo “Literature Discussions Anchor Chart.”)

The children needed practice to internalize these norms, as the following observation shows.

Meridith: Brandi, do you want to say something to Logan at this time?

Brandi: Will you please stop, Logan? ’Cause I’m trying to say something, and you keep on interrupting me and doing funny stuff because everyone’s looking at you. So, can you please be really serious in the group?

(Logan puts his head down on the table, as if upset.)

Brandi: I don’t mean like put your head down.

(Logan sits up.)

Meridith’s reflection

Putting power in the hands of the students produced one of their greatest transformations because it held them accountable and made them leaders. It was an initiative to steer them away from the traditional classroom discourse in which teachers ask questions and students raise their hands to respond. The children quickly learned that I was not the only one who had power. Encouraging students to ask each other for questions, comments, or connections helped them move conversations forward without my support. Those three words were a catalyst for collaborative conversations as children discovered their classmates had ideas to share and that a conversation was a two-way street.

Discussion preparation

Meridith emphasized that students needed to come to the class’s literature discussions prepared. She provided common texts ahead of time, with the expectation that children would read them and record their thinking (things learned, questions wondered, and personal connections) on sticky notes (Moses, Ogden, & Kelly 2015). During informal one-on-one conferences that Meridith regularly had with each child, they discussed their thoughts on the texts and which ones would be good topics to bring up at the group discussion. When students came together, they had comments and questions ready.

In the following exchange from the spring, Meridith explored with the class why thinking about the text beforehand is helpful for discussion.

Meridith: I want you to reread your literature discussion book, stop and think, and use your stickies. If we’re not stopping and thinking while we’re reading, when we come to a literature discussion, are we going to have a lot to say?

Orin: You can’t just be like, if you brought Henry and Mudge’s Big Sleepover, “Well, it was about Henry and Mudge and a big sleepover.” You can’t just say that.

Meridith: Is that a very exciting conversation?

Class: No.

Meridith: So, your conversation needs to be . . .

Bianca: Bigger.

Meridith: Interesting and bigger, I like the way you said that. And one of the ways we achieve that is by using our sticky notes and thinking.

Meridith’s reflection

Initially, I thought stickies might interfere with the children’s reading and thinking. I feared they would focus on spelling or the process of writing rather than on generating thoughtful ideas to share. I was wrong. As I introduced and modeled different uses for stickies, my students used them with great intent. It gave them purpose while reading and something to share during discussion (Kelly & Moses 2018). It is not always easy to think on the spot—sticky notes helped us collect our thoughts before participating, enabling students to voice their ideas and be heard and valued.

Gradually increasing children’s independence

Meridith first taught speaking and listening in the context of turn and talk and whole-group discussions. As students gained independence, they moved into teacher-scaffolded small-group discussions and later small-group discussions with minimal adult support.

Turn and talk

Meridith used turn and talk in a variety of settings— such as during morning message and lessons—not just in literature discussions. For turn and talk, she asked an open-ended question and gave the children two to three minutes to discuss it with their assigned partner. (To increase children’s comfort but still avoid partnering children only with their close friends, Meridith assigned long-term turn-and-talk partners.) Meridith then called the students back together and asked them to share their thinking and what they learned from their partners.

To make turn and talk successful, Meridith started working with students at the beginning of the year to ensure they knew the basics of how to talk and listen. She emphasized the importance of physically turning to face partners and of making eye contact. To encourage engaged listening, Meridith often asked students to retell what their partners had said. In this transcript from the beginning of the year, Meridith modeled asking questions, provided explicit instruction in speaking and listening, and checked in with different student groups.

Meridith: Remember, you want to be looking that person in the eye, straight forward. (Brief pause.) Now, ready? Ask the question. Start with, “How was your weekend?” (Students talk.)

Meridith: You were all chitter-chattering very nicely. I saw you looking each other in the eye, listening. I saw some heads nodding.

(Meridith engages Kelsey in conversation). Kelsey shares that she had a good weekend. Meridith asks what she did and whom she saw. After Kelsey answers, Meridith asks, “Anything else special?” Kelsey talks about a cake. Meridith asks, “What kind?,” and makes eye contact as she listens to Kelsey’s answer.

Meridith: (Turning to the whole class.) Do you see how I asked some questions? Could you ask your friends some questions like that when you’re turning and talking? If your friend doesn’t give you a lot of information, then ask some more questions.

Meridith’s reflection

Turn and talk helped children work on their conversational skills on a small scale. They were expected to use eye contact, responsive body language, and engaged listening with only one person. For many, especially dual language learners, this was the least intimidating conversation type. Having a consistent turn and talk partner helped build strong relationships; as time progressed, partners opened up more. They learned to ask questions, take conversational turns, and add to each other’s thoughts.

Whole-group literature discussion

In August, students began sharing their thinking about books they each had chosen and read independently, something they continued to work on throughout the year. To support children in engaging in these discussions, Meridith gave them a clear framework: One student would share about a book while the others listened. The class knew it was their turn to respond when the presenting student asked, “Questions, comments, or connections?”

As this transcript shows, Meridith provided specific instruction on expected listening behaviors during a literature circle later in the year:

Meridith’s reflection

Whole-group literature discussions were definitely the most challenging. Getting 28 first-graders to care about what each had to say seemed overwhelming; but we kept reviewing listening and speaking expectations, and over time the discussions transformed. Implementing “Questions, comments, or connections?” and utilizing sticky notes helped take whole-group discussions to the next level. Students started to see the value in whole-group discussions as the discussions became a forum for sharing and recommending books.

After the children learned the norms of whole-group literature discussions, they began small-group discussions about a book they had all read. These discussions required sustained adult support to move forward and stay on topic; teachers also ensured that all students had a turn to speak and that multiple students didn’t share at the same time.

In this springtime classroom observation, Meridith guided Evan in order to help him and the other group members learn how to facilitate their own discussion with less adult support.

Meridith calls on Evan. She tells him to wait until he has everyone’s eyes on him. He announces whose eyes he’s still waiting for. Meridith prompts him to say, “Excuse me.” He says, “Excuse me, Beck,” and once Beck looks up, Evan starts reading aloud his connection about a time when he was stubborn.

Meridith’s reflection

Small-group literature discussions were my favorite because they were full of energy. The children loved discussing a common text. At first, they were so excited they often spoke over each other before a student’s thoughts were complete. Because of this, we modeled effective conversation insertions and provided explicit instruction and language frames to help children get back on track. We also found that literature discussion groups were easier to manage with no more than five students.

Less-guided small-group literature discussion

Although the first graders made great strides toward independence and required much less scaffolding as the year progressed, they did not develop the ability to hold deep, on-topic literary discussions without adult support. With practice, however, they internalized discussion norms, took responsibility for moving literature discussions forward, and used strategies for keeping their peers focused (Moses, Ogden, & Kelly 2015).

In the following late spring observation, Eloise helped Alexis identify and understand the author’s message in a story.

Eloise: Oh, I got a good author’s message at the end.

Alexis: What! There’s an author’s message?

Eloise: Yeah. This is in the back too. If someone . . . If someone is being mean, really try hard. Ask, If I were you, then what you want me to do? Make you clean up my mess? Treat others the way you want to be treated.

Alexis: I didn’t know there was an author’s message.

Meredith’s reflection

Alexis’s lightbulb moment was powerful. She was listening to her friend and walked away with a deeper inferential understanding, becoming aware that the author was conveying a message beyond just the surface story. These sorts of incidents occurred often and supported students’ abilities as a community to construct meaning. With smaller groups (no more than five children) and discussion norms in place, the children were more successful. As the year progressed, they required less support. Providing children with strong scaffolds and giving them space to hold meaningful discussions taught them to listen; more important, it taught them to care about what others had to say and to learn from each other. Ultimately, collaborative conversations helped students find their voices.

Speaking and listening leads to learning

Throughout the year, the children demonstrated deeper literary understandings because they spoke and listened to each other. One day, after taking a reading assessment required by the school district, Meridith overheard the children talking about how easy it was. Eloise explained why: “They didn’t even ask us to infer!”

At the end of the school year, Meridith summed up her experience:

When children participate in collaborative conversations, they use more inferential thinking as opposed to literal recall of the text. Since I began initiating collaborative conversations, I have noticed that the children take more risks and share ideas beyond what is right there in the text. Without these conversations, we miss the opportunity to address social injustices, share life experiences, and express compassion and empathy.

When I think about whether or not literature discussions are effective, I think about the moments that would never have happened had we not given students the chance to talk in an environment that truly nurtured and valued student voice. Mateo might never have discovered his love for megalodons, Alexis might still be searching for the author’s message, and Maria might have gone the whole year without sharing a single idea. It’s not so much about the routines and procedures, but more about what the routines and procedures allow you to accomplish.

We place great value on encouraging, nurturing, and sharing young children’s voices. Children’s thinking and meaning-making experiences with texts bring richness and engagement to literacy. Throughout this yearlong collaborative study, we identified important strategies for supporting the development of speaking and listening skills with first-grade students. These instructional ideas provided opportunities for supporting deeper literary conversations with and among young learners.

References

Biffle, C. 2013. Whole Brain Teaching for Challenging Kids (and the Rest of Your Class, Too!). Yucaipa, CA: Whole Brain Teaching LLC.

Baker, L., M.J. Dreher, & J.T. Guthrie, eds. 2000. Engaging Young Readers: Promoting Achievement and Motivation. Solving Problems in the Teaching of Literacy series. New York: Guilford.

Carrison, C., & G. Ernst-Slavit. 2005. “From Silence to a Whisper to Active Participation: Using Literature Circles with ELL Students.” Reading Horizons 46 (2): 93–113.

Clay, M.M. 1991. Becoming Literate: The Construction of Inner Control. 2nd ed. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hall, N. 1987. The Emergence of Literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Harvey, S., & H. Daniels. 2015. Comprehension & Collaboration: Inquiry Circles for Curiosity, Engagement, and Understanding. Rev. ed. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Johnston, P.H. 2004. Choice Words: How Our Language Affects Children’s Learning. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse.

Kelley, M.J., & N. Clausen-Grace. 2013. Comprehension Shouldn’t Be Silent: From Strategy Instruction to Student Independence. 2nd ed. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kelly, L.B., & L. Moses. 2018. “Children’s Literature That Sparks Inferential Discussions.” The Reading Teacher 72 (1): 21–29.

Kirkland, L.D., & J. Patterson. 2005. “Developing Oral Language in Primary Classrooms.” Early Childhood Education Journal 32 (6): 391–95.

Moses, L., M. Ogden, & L.B. Kelly. 2015. “Facilitating Meaningful Discussion Groups in the Primary Grades.” The Reading Teacher 69 (2): 233–37.

NGA (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices) & CCSSO (Council of Chief State School Officers). 2010. Common Core State Standards. Washington, DC: NGA & CCSSO.

Nystrand, M. 2006. “Research on the Role of Classroom Discourse as It Affects Reading Comprehension.” Research in the Teaching of English 40 (4): 392–412.

Serafini, F. 2009. Interactive Comprehension Strategies: Fostering Meaningful Talk about Text. New York: Scholastic Teaching Resources.

Wells, G. 1999. Dialogic Inquiry: Towards a Sociocultural Practice and Theory of Education. Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive, and Computational Perspectives series. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Photographs: 1, 3 © Getty Images; 2 courtesy of the authors

Laura Beth Kelly, PhD, is an assistant professor of elementary literacy at Rhodes College, in Memphis, Tennessee. She has National Board Certification in early to middle childhood reading and language arts. [email protected]

Meridith K. Ogden has worked as a first- and secondgrade classroom teacher in the greater Phoenix, Arizona, area for the past 13 years. She is currently a first-grade demonstration teacher in the Paradise Valley Unified School District, where she shares her passion for reading workshops with other educators. [email protected]

Lindsey Moses, EdD, is an associate professor of literacy education and the program coordinator for the master’s in literacy education program at Arizona State University, in Tempe. Lindsey conducts long-term research on language and literacy in diverse elementary classroom settings. [email protected]