Muddy Play. Reflections on Young Children's Outdoor Learning in an Urban Setting (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Mary Jane Moran, Voices Executive Editor

Hannah Fruin’s inquiry about the benefits of young children’s muddy play was inspired by her belief that muddy play is a valuable experience. It helps children engage in the natural world through the manipulation of a range of materials during rich play encounters and through sensorial experimentation. But she was surprised that not all children desired to play in the mud. Her close observations revealed there was a range of comfort among the children with "getting dirty." Becoming curious, Hannah “set an intent” to find out whether the beliefs and experiences of important adults in young children’s lives surrounding muddy play influenced how children approached muddy play. In essence, her research is structured as a "nested approach" for understanding what children had learned about muddy play from others and in other contexts. Imagine that her inquiry was based on positioning the children's muddy play in the middle of a series of circles, with the first circle being children's home lives, the second being their parents' childhoods, and the final circle being their teachers' beliefs and experiences. This nested approach offers a way to link spaces and relationships that have influenced children's thoughts and actions. This knowledge, then, would inform Hannah's teaching approach for each child.

As teachers, we are challenged to create learning experiences for children that are meaningful and joyful and that promote the development of their knowledge, skills, and dispositions. In this study, Hannah goes beyond wondering what might be developmentally appropriate for young children—that is, what kinds of materials to offer, what questions to ask, or how long to plan for children to be outside involved in muddy play. Her preparation for practice was also informed by what she discovered about each child’s parents’ childhood experiences with muddy play and other play spaces and the beliefs held by some adults that muddy play on a chilly, rainy day can harm children’s health. As a result, Hannah reminds us that our preparation to teach is informed by multiple points of view and multiple sources of knowledge that go beyond a well-prepared activity, carefully selected materials, or curriculum guidelines. Our preparation to teach also includes knowledge of our own childhoods, children’s home environments, and the childhoods of their parents.

Being under the open sky and in close contact with the natural world is widely acknowledged as a crucial experience for young children’s learning and development. Loose parts found in natural environments, such as stones, sticks, water, sand, and mud, are inherently open-ended and can be used by young children in ways that support their constantly changing ideas and avenues of exploration (Tovey 2007). I was reminded of this by a video of my 3-year-old niece playing on a beach. As I watched her rubbing sand onto her hands and feet, patting the wet mixture and watching it splatter, I thought about all the children I have seen in similar states of contentment playing with nature’s resources. The endless learning opportunities offered through these loose parts in the outdoor environment enable children to feel at ease in their environment and in control of their own explorations. To better understand this value of outdoor learning, I engaged in a study during my fifth year of teaching a class of 28 children ages 2 to 4 in an urban South East London nursery school (which, in much of the US, would be called a multiage preschool).

The nursery school was next to a busy road surrounded by several construction sites. My colleagues and I believed that the nursery’s open garden was a potential haven for rich outdoor learning experiences. Nevertheless, I noticed some inconsistencies in the ways families, children, and even some staff approached outdoor play when there was a risk of getting dirty and/or wet. These conflicting attitudes motivated me to explore muddy play. This was a particularly significant inquiry at the time of my study, as 53 percent of our families lived in apartments without direct access to natural outdoor spaces.

The open-mindedness of mud is well suited to supporting children's thinking.

I define muddy play as any form of playing outdoors that directly involves mud, such as mixing soil and water to make mud cakes or squelching feet in a mud pit. Muddy play also indirectly involves the risk of getting muddy—for example, digging for worms or exploring a muddy woodland area. My decision to investigate children’s muddy play reflected my strong early childhood ethos that young children learn best when given opportunities to freely play and explore, led by their own interests and motivations, alongside the support of attentive and intentional adults who nurture and extend their learning (Bruce 2011; Fisher 2016).

As I contemplated how to conduct my study, I was sensitive to others’ concerns about muddy play that would limit children’s access to the learning opportunities offered to them. For example, a child whose parent had warned them to keep their new shoes clean or to stay dry for fear of catching a cold was more likely to approach muddy play differently than the child who arrived in rubber boots ready to explore any part of the garden. I became concerned that worries about clothing and children’s health could be overshadowing the potential for muddy play to be appreciated as a valuable learning experience.

As more time is spent in confined spaces detached from nature, particularly in urban areas, there is a risk that playing and learning in the great outdoors will become a rare experience for children, with fears surrounding health and safety obscuring its powerful worth (Gill 2007; Solly 2015). From these thoughts and motivations, I was determined to answer three research questions:

-

What are the attitudes of parents, staff, and children at my nursery toward muddy play?

-

How do these attitudes affect children’s muddy play experiences?

-

What are the benefits of muddy play to children’s learning?

Methodology

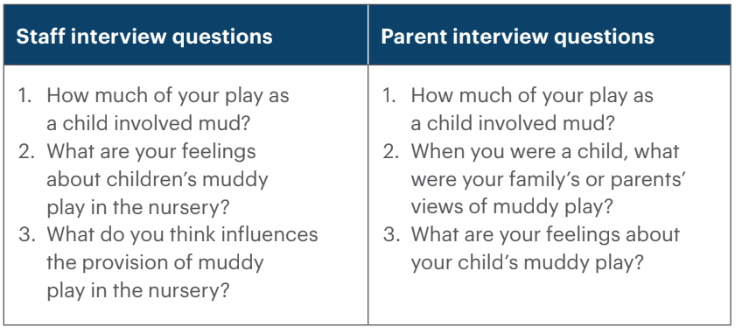

To begin to understand the varying views of muddy play as a learning experience, I conducted interviews with four staff members and four parents at my nursery, (see questions below). In order to capture a range of responses and experiences, I chose to interview one teacher, two higher level assistant teachers, and one assistant teacher. Based on my knowledge of these staff members (who had been my colleagues for several years), I already knew that their views differed regarding outdoor play and children getting messy, and I hoped that interviewing these chosen individuals would result in a wide range of ideas concerning children’s muddy play.

I also did a series of observations over one week of four children engaging in muddy play. Through my role as an early childhood teacher researcher, I used my knowledge of the children to select two who were mostly unfazed by getting messy and who played outside regularly and two who spent more time indoors and tended to avoid messy play. Again, this was an attempt to capture a range of varying responses to muddy play. The parents I interviewed were the parents of these four children. Guided by action research methodology, I engaged in a cycle of observing the children followed by reflection. This step was then followed by acting—including guiding children’s muddy play settings—and began the cycle again with observation. I briefly took photos during my observations and I made notes afterward in order to reduce interruptions and distractions during the children’s play. This was also the case with interviews, which I recorded and later transcribed. In addition, I recorded my thoughts and key ideas in a reflective journal after each observation and interview. I also added notes to the journal after conversations with children in the study.

My research took place toward the end of the school year in June. Observations of the children were carried out over one week, with interviews taking place over the following two to three weeks, according to the interviewees’ schedules.

Children in the nursery had free access to the outdoor space for most of the day. The garden consisted of a mud kitchen area with open access to a rain water barrel and troughs of soil as well as herbs and plants, flat surface areas for adaptable climbing apparatuses and bike riding, a pond area, a sand pit, vegetable and digging patches, a natural wildlife area with logs and plants, construction areas with large wooden blocks, and a grassed area with a hill and a tunnel.

Toward the end of the research period, I chose to promote muddy play with colleagues and families by helping to arrange a “Muddy Stay and Play” event for children and families held on International Mud Day (McAuliffe, n.d.). During the event, I also invited parents to complete a short questionnaire to add further depth to my understandings and overall findings. Of the 15 parents present, 10 completed the questionnaire, which consisted of the following three questions:

-

How excited about this event was your child before the event?

-

What were your feelings about your child engaging in muddy play before this event?

-

What were your feelings about your child engaging in muddy play after this event?

Before I observed children engaged in muddy play, I individually showed each of the four children photos from a recent edition of the magazine Nursery World that depicted children in different parts of the world using mud. The photos showed children playing in muddy sand on a beach, digging in mud on the edge of a farm, making treats in a mud kitchen, and living in a mud house. My intent was to provide an initial incentive for the children to enter the realms of muddy play, which they were invited to do after our discussion of the photos. This step was particularly important for the children who had not yet naturally engaged in play of this nature.

Findings

Adults’ attitudes about muddy play

The adults’ experiences with muddy play when they were children varied, and this tended to influence their understandings of its potential benefits. Most of the issues adults raised fell into three categories: access to natural spaces, how to deal with the weather, and what the children are learning.

Access to natural spaces

One of the higher level assistant teachers, Tom, remembered spending a large amount of time outdoors as a child and using mud as a play resource. He said, “I remember just being left on my own in the garden to do things like making potions with flowers and mud.” He also recalled family visits to woodland spaces with lots of “walking through mud in the woods in your wellies and that lovely suction feeling and the sound of when it got stuck.” He later added, “Mud was just part of our many resources of play.”

These highly positive memories of playing with mud and being free in natural spaces had influenced Tom’s approach to supporting muddy play for the children he taught. For children’s muddy play, he said, “I think just go for it,” and he talked in detail about some of the muddy play provisions he offered the children.

I am fond of the mud kitchen; it takes me back to all that mixing and bits that I did. And I like making mud pits for the children—there's that childhood memory of standing in it and squelching in the mud in your welly boots. There's another staff member I know likes it, so I often call her over to just wallow in it too.

Mud was a significant part of Tom’s childhood, and his fond memories of playing freely with mud resulted in him recognizing the importance of providing opportunities for this type of play. If children see adults approaching muddy play with enthusiasm, they will be more inclined to join in and “wallow in it too.”

I wondered what impact a more urban childhood experience would have on attitudes about muddy play. Holly, an assistant teacher, had grown up in inner London and could not remember any of her childhood play involving mud.

Hannah: How much of your play as a child involved mud?

Holly: None, none. I didn’t really want to get messed up because I just went straight to school; I didn’t go to nursery.

Hannah: Why do you think you didn’t get messy at school?

Holly: I think it wasn’t really on offer and I just hadn’t experienced anything messy.

Living in an apartment in inner London and not attending any play-based settings before starting formal education meant that Holly’s opportunities to engage in outdoor messy and muddy play as a child were essentially nonexistent. When she began teaching young children, she had no experience or understanding to draw from concerning the joys and possibilities of muddy play in the learning lives of young children.

Nonetheless, Holly recalled a shift in her considerations about muddy play: “Over a course of time, I got used to it. I saw the joy in their faces, and I want[ed] the children to experience what messy feels like.” She spoke of the value of playing outdoors for children who cannot experience such activities outside of nursery because “not everyone has that space, so the only place they can get that mud experience is here.”

I saw echoes of Tom’s and Holly’s experiences in the parent questionnaire. Six parents reported they felt more positive about muddy play than they had before the “Muddy Stay and Play” event, and the remaining four felt positive about muddy play experiences both before and after it.

Weather worries

For another assistant teacher, Aruna, who had moved to England as a young woman after spending her childhood in India, the cold weather conditions of the English winter were a cause for concern. As a child, Aruna remembered plenty of outdoor play involving mud. She recalled, “I was born on a farm. You can imagine in India there’s no tarmac, just mud. So outdoors play is muddy play.” She went on to recollect a muddy play experience in rice fields.

You know when they . . . plant [the rice] in the fields, they have to make it really muddy. . . . We were very little and [the mud went up] . . . to our knees; we just go inside the mud there and we loved that, it feels so nice. And when we try to take our legs out from that mud we use all our muscles—you can imagine how good is that, make me strong.

Similar to Tom’s memory of being stuck in the mud in his rubber boots, Aruna had fond memories of immersive muddy play, with no concerns about the inevitable messiness that goes with it. As a higher level assistant teacher in England, however, outdoor muddy play was not so carefree for Aruna because of her belief that if children got wet it would cause “infections, colds, flus, that sort of thing.” Aruna seemed to accept this concern as a cultural difference and recognized it in families within the nursery who had also moved to England from other countries.

And especially this center, it’s a multicultured center and people’s views are different from different countries. I remember I didn’t let my children out in the winter to play with mud and water because I wasn’t used to it from India, and I listen to parents here complain of same things, so I understand both cultures.

Aruna went on to explain that the approach from other adults at the center needed to be more carefully considered in terms of potential health risks involved with muddy play in the winter. She suggested that sessions of outdoor play in the winter be limited to 30 minutes, adding, “There needs to be some rules and regulations with these things. I think mud and water in January, December—not good.” Out of all the staff members who were interviewed, Aruna had some of the most joyful childhood memories of muddy play, yet she also had the most concerns about the health risks involved with it.

Muddy play: Unsophisticated mess?

Learning through play—particularly in the case of messy play—is a process of discovery and exploration, without a focus on a specific end product (Gascoyne 2017). The open-ended nature of muddy play as a loose part resource that serves any purpose a child chooses (Tovey 2007) may be at odds with those who expect children’s learning experiences to be planned and outcomes based. This is another strand of thought that emerged when considering adults’ attitudes toward muddy play and what it offers to enrich children’s learning.

For example, one parent, Suzanne, could not recall any memories of playing with mud as a child beyond “careful gardening.” At our nursery, several children had recently used mud as sunscreen, which some teachers saw as a valuable reenactment of sun safety, reinforcing children’s developing understandings. But Suzanne saw it differently. Thinking of her childhood, she noted, “We would do gardening rather than paint mud sun cream on ourselves. So, I guess in that way it was more focused, and more sophisticated, more grown up.” Suzanne considered the controlled and focused element of gardening to be more meaningful than the messy sunscreen play. She also talked about the focused painting she did as a child with her parents who had “quite a precise style” (they were artists). She wondered “if that sort of filters through”—particularly as she, herself, had become an artist. She continued, reflecting on the subject of messy art experiences for her children at home.

When we do painting, we have an assigned area of our open-plan living space that is our craft table. . . . It’s always set up, but it stays within that area. . . . Actually we control felt tip pens; I’ll sit with them and they’re allowed three at a time, then we put the lids back on with a click and put them back, swap them for some others. So, I suppose we are quite regimented . . . anything too messy is monitored.

This controlled approach to play that limits the risk of mess may have impacted Suzanne’s daughter Lucy’s consideration of messy play in other areas of her life. Suzanne recalled taking Lucy at the age of 2 to a messy play session at a local community center, during which the children were encouraged to wear overalls, roll in paint, and use their paint-covered bodies to make marks on large paper attached to the walls. Suzanne remembered, “She [Lucy] looked at me as if to say, ‘No way. I’m not doing that,’ and as if to say, ‘What are these crazy children doing?’” Of course, the activity was likely aimed at cultivating children’s physical and sensory development, but to Lucy, it seemed chaotic and unnecessary.

At the nursery, it could be expected that Lucy would approach muddy play with some trepidation, perhaps having absorbed her mother’s perception that play involving mess needs to be controlled and purposeful. While Lucy did engage in muddy play with my encouragement, her play largely remained focused and precise, as will be further examined in the next section of this article related to the benefits of muddy play for young children.

The benefits of muddy play for children’s learning

Based on my observations of children engaging in muddy play, I saw numerous benefits to their learning and development, including internalizing routines, developing confidence, and engaging in critical thinking. Here, I have chosen to to share my analysis of the key benefits of muddy play for three of the four children.

Internalizing routines

Young children need to learn how to follow the rules and routines of home, nursery, and the wider world, and their exploration of roles and experiences through imaginative play can support this goal. Imaginative play often provides an opportunity for children to “replay their experiences so as to process, understand and internalize them” (White 2008, 88).

Through my role as an early childhood teacher researcher, I knew that one of the children I was observing, Lewis, had needed extra support in order to follow certain routines in nursery and at home. By the time my study took place, however, Lewis had made significant progress in his understanding of and ability to follow daily routines, such as toileting and washing hands. I observed that Lewis’s muddy play—its messiness and his learning about cleanliness—provided a means of playing out and internalizing the routines he was beginning to independently follow. For example, when looking at the Nursery World photos, Lewis focused on one of the children’s muddy bare feet and repeatedly pointed out that they were dirty. Notes from my reflective journal written after our discussion explain, “Lewis often came back to the boy’s muddy feet, pointing at them saying, ‘Look, it’s dirty. Need a baby wipe. Need welly boots.’”

Because Lewis began the school year needing a great deal of support to become more independent in his routines of putting on his shoes or washing his hands, it felt significant to me that he was now recognizing and verbalizing the routines the child in the photo would need to follow in order to get clean after playing in the mud. Out in the garden, Lewis was able to play out these routines. For example, he noticed a muddy puddle on the ground and gasped before dashing off to put on some rubber boots from the communal supply in the garden, returning to proudly show me: “Got welly boots!” After some time mixing mud in a bowl, he looked at his muddy hands and said, “Uh oh, mucky hands,” showing them to me and laughing. He noticed a bowl of muddy water and began rubbing some of the mud off his hands. “Look, washing hands!” he called out to me, announcing proudly when they were “all clean.” Actually being muddy was not a concern for Lewis. Rather, the messiness of mud, which led to the reenactment of washing his hands and proudly putting on his rubber boots, provided an opportunity for him to play out and validate his grasp of important daily routines and self-care skills.

Developing confidence

Being outdoors in an environment with constantly changing weather provides exciting and dynamic experiences for young children. The outdoors is a vital part of young children’s learning (White 2008) that offers unique experiences. This notion was of particular significance for one of the children, Chloe, who lived in an inner London apartment without direct access to outdoor space. For her, the garden seemed to be an unfamiliar, daunting place.

Prior to my observations of Chloe’s engagement with muddy play, an animated discussion about the Nursery World photos took place in which she related lots of the mud in the photos to food. The muddy sand on a girl’s face on the beach was “chocolate,” and the watery mud being poured in the mud kitchen was “juice and cupcakes.” I thought Chloe would thrive with such an open-ended resource as mud at her fingertips, with its versatility supporting her imaginative ideas. Fortunately, our discussion about the Nursery World photos provided enough intrigue and motivation for her to go and look for mud in our nursery garden with new enthusiasm, helping her move beyond the safety of the four walls of the classroom.

Despite this initial enthusiasm to go out to the garden, Chloe watched with uncertainty after noticing Lewis in the mud kitchen busily filling a cupcake tray with mud and water. Fulfilling my role as teacher, with a responsibility to respond to children’s feelings and to “keep the momentum of an interaction going” (Fisher 2016, 167), I asked Chloe if she wanted to join in. She shook her head but continued to watch Lewis with intrigue, so I found a cupcake tray and a spoon and modeled imaginative muddy play. After a minute or so, she picked up her own spoon and helped me fill the cupcake trays with dry soil from a wooden trough. I showed her where the herbs were growing nearby and how she could sprinkle the leaves over our cupcakes, which she began doing independently. When some muddy water splashed onto her clothes, she showed me with a concerned expression. I reassured her the mud would wash out and showed her some mud on my clothes, after which she returned to the important job of decorating her cupcakes.

The versatility of mud meant that Chloe was able to engage with muddy play in a way that met her own interests regarding imaginative food play. After this form of muddy play was modeled for her, she felt able to join in, embarking on a discovery of muddy play. For her, the dry soil and leaves created manageable mess that she controlled by adding small amounts of water as she gained confidence. Chloe may have been “overcome with uncertainty” (Fisher, 2016, 14) had she been left alone in this situation, but with my preparation and support, muddy play afforded Chloe an opportunity to build confidence and learn from both a knowledgeable other and a new experience (Vygotsky 1978).

Engaging in critical thinking

The open-endedness of mud as a play resource means it is well suited to supporting young children’s critical thinking. As children “tinker with loose parts,” engineering them in ways that reflect their emerging thoughts and interests, problem solving and higher order thinking skills are developed (Daly & Beloglovsky 2015, 8). Lucy used mud in a way that complemented her precise, focused approach to learning and nurtured her critical thinking. She preferred to spend her time focused on making things indoors, perhaps influenced by the carefully monitored craft area in her home and her mother’s precise drawings as an artist.

My initial discussion with Lucy about the Nursery World photos sparked a fascination about a photo of Kenyan children and their house made of mud. She wondered how they had built a house with mud and was amazed when I told her not everyone in the world has access to bricks and cement. Our subsequent visit to the garden led to Lucy wanting to make her own house of mud. A carefully mixed pot of mud along with some large stones provided her with the materials to begin building her house. As she spooned her muddy cement mixture onto a baking tray that she used as a solution to leveling the uneven ground, she was not afraid to remove parts of her house and reposition them. The fluidity and changeable nature of the mud and stones permitted Lucy to rethink her design.

For Lucy, the muddy play experience afforded her an opportunity to build confidence using a messy material. Her motivation to think critically and follow through on her idea of building a mud house provided the purpose she needed for engaging in muddy play and overrode her concerns about getting messy.

Later, at the “Muddy Stay and Play” event, the experience also seemed to help Lucy see the value of enjoying something just for the experience, rather than focusing on an end product. After being given time and space to watch her peers, laughing as they whizzed down a muddy slip-n-slide, Lucy eventually joined in. She spent the rest of her time going up and down the muddy slide, unfazed by how muddy she was.

Providing muddy play in your setting

If an outdoor learning environment does not already have muddy spaces, such as woodland areas and digging patches, some simple adjustments can be made in order to provide valuable muddy play experiences. Wooden troughs, planters, and even unwanted large truck tires (which in the past I have acquired for free from local tire stores) can be filled with soil and accessed freely by children. Having a water barrel or outdoor tap nearby means that children can independently create their own mud concoctions and mud pits, in control of how much mess they wish to create.

The mud kitchen was a popular area for muddy play in this study’s learning environment, and it can be inexpensively recreated in other settings. While scrap wood and an old sink can be fashioned together by someone with woodworking skills, a simple arrangement of small wooden tables can also create an effective mud kitchen space. All you really need is a good supply of mud and water, along with old pots, pans, and utensils for lots of open-ended, imaginative play.

Ultimately, the provision of muddy play can only be effective if children are supported by adults who understand and promote its benefits for children’s learning. Ideally, staff should communicate regularly with families about the importance of muddy play in outdoor learning—especially in urban settings where outdoor play opportunities may be limited. Additionally, having a good supply of rubber boots, waterproof suits, and spare clothes, and ensuring that children are dressed warmly in colder weather, may help to ease any concerns surrounding the health and safety of children engaging in muddy play across the seasons.

Acknowledging International Mud Day can be an effective way for programs to promote the benefits of muddy play and to celebrate it with both families and staff, helping to uphold this type of play as a globally recognized and valuable form of learning. Finally, regularly sharing examples of muddy play in your setting and making muddy play visible in displays, in children’s journals, and during family meetings will help embed muddy play as a continuous key element of your school’s ethos and approach to learning.

References

Bruce, T. 2011. Learning Through Play: For Babies, Toddlers and Young Children. London: Hodder Education.

Daly, L., & M. Beloglovsky. 2015. Loose Parts: Inspiring Play in Young Children. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf.

Fisher, J. 2016. Interacting or Interfering. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

Gascoyne, S. 2017. “Patterns and Attributes in Vulnerable Children’s Messy Play.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (2): 272–91.

Gill, T. 2007. No Fear: Growing Up in a Risk Averse Society. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

McAuliffe, G. N.d. “International Mud Day: Celebrating Our Connection to Each Other and Nature through the Earth.” Practical Wisdom: Gillian McAuliffe. Blog. www.pracwisdom.com/international-mud-day.

Solly, K. 2015. Risk, Challenge and Adventure in the Early Years. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Tovey, H. 2007. Playing Outdoors: Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenge. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Edited by M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

White, J. 2008. Playing and Learning Outdoors: Making Provision for High-Quality Experiences in the Outdoor Environment. New York: Routledge.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Hannah Fruin, MA, is an early childhood teacher who taught in a nursery school in London for several years and is currently living in Melbourne, Australia. Throughout her early childhood practice, Hannah has explored and researched outdoor play, children’s risk-taking, and picture books and storytelling. [email protected]