Our Proud Heritage. Building the Kindergarten Curriculum

You are here

In 1950, Betty Kirby’s kindergarten classroom is a busy place. The large, interconnecting wooden blocks designed by Patty Smith Hill have a central role. The children, with some teacher assistance, have built an ocean liner that is big enough for 10 or more children to play inside. Tickets that the children made themselves are on sale at the ticket counter. A few passengers sit in deck chairs at one end of the ship as a waiter delivers a plate of sandwiches made of construction paper. A child rolls a cart, also made of Hill blocks, that holds luggage to be carried up the gang plank to the ship. A deckhand checks the cardboard lifeboats to be sure they move up and down on the pulleys the children have learned to maneuver. Other sailors swab the decks with mops and check the anchor. The tugboat the children have built waits to help guide the big ship. The captain is at the wheel, ready to begin today’s voyage. The children are literally building their curriculum as they create all they need to make the voyage a success. (Kirby, n.d. a; Kirby, n.d. d).

These children lived near Chicago. They had seen the huge ocean liners on Lake Michigan. These boats were familiar and interesting, but the children knew little about their many parts and the people who worked on them. Their teacher, Betty Kirby, used Patty Smith Hill blocks to help them build their knowledge. She knew that children could learn accurate, meaningful information through their own research that would, in turn, inform their play—whether it was information about a ticket or a tugboat. She taught these children to become confident and capable learners who eagerly gained and shared knowledge through their work and play.

This article will introduce the Patty Smith Hill blocks and describe how they helped one teacher build a curriculum and intentionally plan and teach in ways that engaged children in deep study of topics they could learn about through firsthand experiences in their own community. These stories, pulled from Kirby’s own notes from her teaching in the early years of her career (1950–1954), describe different units that were explored over the course of a typical school year, which echo current understandings of developmentally appropriate practice.

M. Elizabeth Kirby

M. Elizabeth Kirby (1911–2005), otherwise known as Betty Kirby, was a 1933 graduate of the National College of Education in Evanston, Illinois. The Hill floor blocks were an integral part of teaching in the classrooms of The Children’s School, a nursery school through junior high school that served as a demonstration school for National College. Curriculum Records of the Children’s School, published by the college in 1932, includes three photographs of the kindergarten classroom. The Hill blocks appear in each of them with the comment that “the interest in construction and dramatic play has been encouraged by the availability of large floor blocks” (National College of Education 1932, 31). Kirby’s copy of this text has information about the blocks extensively underlined.

Kirby began teaching kindergarten in Riverside, Illinois, a Chicago suburb, in 1946 and continued until her retirement in 1975. Over the course of her long career, Kirby documented her teaching through classroom photographs, curriculum materials, and handwritten notes and plans. These materials provide a detailed picture of the many ways she integrated Patty Smith Hill blocks into her work with children. The use of Hill blocks as an essential part of classroom activity is indicated by one of Kirby’s goals for her children: “to help construct, play in and think through for a period of weeks group interests such as the making and operating of a store, a train, or an airport” (Kirby, n.d. c). The following stories from Betty Kirby’s classroom show how this goal was addressed through representative samples of her teaching in the early 1950s.

Patty Smith Hill Blocks

Patty Smith Hill (1868–1946) was a dynamic pioneer in early childhood education. She served as the first president of the National Association for Nursery Education, which later became the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). She brought the emerging science of child study and Dewey’s ideas of progressive education into the kindergarten classroom. Hill viewed children as competent thinkers who learned through “the dramatization of the activities of human beings in vital social relationships” (quoted in Sherwood & Freshwater 2013, 165).

To support this kind of playful and child-directed learning, Hill developed a new and innovative block system to encourage active and full-body play. Her description states: “The new blocks are much larger, some being a yard in length, and are made of heavier wood, in order to call into use the large fundamental muscles of the child’s whole body” (quoted in Sherwood & Freshwater 2013, 166).

The block system included various kinds of connectors and wheels that allowed the children to work together to build buildings and vehicles that were strong enough to climb on and play in, thus encouraging children to engage in ongoing explorations of the world of their everyday lives. Because of the blocks’ size, the children learned to collaborate to create structures for play, often based on a topic of common interest such as trains or a store. These structures supported ongoing play and would typically remain in a classroom for several weeks at a time (Snyder 1972, 261; Cuffaro 1999, 72).

For more on Patty Smith Hill, see “NAEYC’s First President: Patty Smith Hill” by Betty Liebovich, published in the March 2020 issue of Young Children.

An Approach to Teaching, Learning, and Setting Goals

Kirby created a list she titled “Goals for Each Kindergarten Child,” which summarized in 22 goals what she hoped to accomplish in her classroom over the course of a year. The first goal was for children “to learn to live freely, fairly, and happily in the group.” The final goal in the list was “to live life fully and well because this is a year of [their] life and not just a time to get ready to live” (Kirby, n.d. c). The remaining goals in the document showed how she hoped to help children reach those two bookending goals. These goals were remarkably aligned with aspects of what is considered developmentally appropriate practice in today’s early childhood settings. Kirby wanted children to make decisions, act on them, and evaluate the results. She wanted them to increase their vocabulary so they could “think accurately and converse intelligently” and to act on their curiosity.

Kirby believed it was her responsibility to provide careful, accurate information to her students. She also believed it was her responsibility to provide resources the children could use to find information for themselves. In the 1950s, that meant providing books, photographs, and other resources related to the topics they were studying. The Hill blocks gave the children the opportunity to use that information and process it through play. It was active play, but it was active thinking too.

The children engaged all their senses through their dramatic play with the block structures; the songs and poems they learned related to the topic; the visual representation of their learning; and the planning, building, and cooperation required to use the Hill blocks. The children truly lived “fully and well” in her classroom.

Starting the Year: Building Background and a Market

We can build what we know. We can make what we need.

—Betty Kirby

Kirby would begin the kindergarten year as kindergarten teachers still do today. September was spent “learning control in transitions from one activity to another” and “rules for orange juice period,” as her records show. She helped children learn simple skills like using scissors and guided them as they began exploring and learning how to use the Hill blocks. Their play with the blocks started with more familiar and basic building, such as placing blocks flat on the floor to become roads for toy cars and constructing simple fences for toy farm animals. As the month progressed, Kirby showed the children ways to connect the blocks for more stability. They began to build walls and basic structures.

Toward the end of the month, Kirby began a study of fruits and vegetables by bringing in various kinds of produce sold at small fruit and vegetable markets from the community. Children began to study how fruits and vegetables grew and were harvested through reading books and examining the produce. Over several weeks, they began working together to build “markets” for sustained dramatic play. These were their first large-scale building structures with the blocks.

The children made fruits and vegetables out of construction paper to sell. Children took on the roles of shopkeepers, customers, and the farmers who delivered the produce—roles that were familiar to them. They created a wagon made from the blocks, and they stocked the market with a combination of real fruits and vegetables along with produce they made from construction paper and clay. At the workbench, they made baskets and boxes to hold the produce. Through this process, Kirby guided the children to recognize that they had the knowledge, skills, and resources for their market to be like a real one. For example, the children engaged in science by exploring real fruits and vegetables and playing with “piles of seeds” (Kirby, n.d. b). They sprouted corn and pumpkin seeds and were eventually able to sell pumpkins at their market for Halloween.

At the conclusion of the market unit, each child made a 12-by-18-inch poster with construction paper cutouts to illustrate “something true” about a fruit or vegetable to share what they had learned (Kirby, n.d. b). This might have been a detailed representation of an ear of corn or a tomato, demonstrating that they had learned to make careful observations and could share those observations with others.

The community market was a perfect way to introduce building a familiar structure with the unfamiliar blocks. It engaged children in a kind of role play connected to the larger social world of their town. It also gave them their first experience with documenting their own learning, something they continued to do with increasing complexity throughout the year. The children’s play and exploration were meeting Kirby’s goals for their learning by giving them the opportunity to work together using the Hill blocks to accurately recreate a piece of their familiar world in the classroom. This provided the setting for them to deepen their understanding of the roles of businesses and jobs in their community.

Let’s Build a Train! A Wintertime Unit on Transportation

They are ready for meaningful play, creative experiences, and an enlarged vocabulary that will broaden their concepts and help their limited thinking to become unlimited.

—Betty Kirby

Transportation was, and still is, a common topic to explore in early childhood classrooms. Many young children are fascinated by vehicles, and the children in Kirby’s classroom were too. This kindergarten’s location in a Chicago suburb made a train unit especially appropriate, as trains were part of children’s daily lives. Trains ran through the community regularly, and the local train station was within walking distance of the school. The children had family members who rode commuter trains to jobs in the city. Because many of the children rode trains to visit relatives over the winter holiday, Kirby identified January as a good time to learn more about them.

Kirby had 10 pages of detailed, handwritten notes and sketches that included information such as precise names for train cars and engine parts, job titles and responsibilities, signal light patterns, how track switches worked, and how the round house was used. One of her goals for each kindergarten child she taught was “to increase [their] vocabulary by leaps and bounds, so that [they] can think accurately and converse intelligently about what [they see and hear]” (Kirby, n.d. c). She made sure that she had accurate information to share to support the children in meeting this goal.

While a unit on trains occurred every year in her classroom, the children’s ideas, questions, and interests helped shape how the study unfolded in different ways. In a description of the train unit in 1950, Kirby wrote, “We vote to take down a large house and garage of blocks so there will be more room to play train . . . Billy says, ‘How will we make it?’ ‘We’ll make it any way we want it,’ I answer. ‘Maybe we will even make signals and gates.’ ‘Yes’, says Bill, ‘Gates . . . That’s going to be compalacated [sic]’” (Kirby 1950).

Kirby posted photographs of train engines and various kinds of train cars around the room, low enough for the children to examine them carefully. She had a large collection of fiction and nonfiction books about trains that she read to the children and made available for their use. Her class walked to the nearby train station to see what they needed to include in their constructions. The children learned the parts of the engine and the differences between a diesel engine and a steam engine through their observations of local trains and the many books and photographs Kirby provided. They learned to identify the different types of train cars. They listened to recordings of train sounds from her record collection, sang songs about trains, and listened for the sounds of trains traveling nearby. They began making paintings of trains and building simple representations of trains with the Hill blocks.

Kirby posted photographs of train engines and various kinds of train cars around the room, low enough for the children to examine them carefully. She had a large collection of fiction and nonfiction books about trains that she read to the children and made available for their use. Her class walked to the nearby train station to see what they needed to include in their constructions. The children learned the parts of the engine and the differences between a diesel engine and a steam engine through their observations of local trains and the many books and photographs Kirby provided. They learned to identify the different types of train cars. They listened to recordings of train sounds from her record collection, sang songs about trains, and listened for the sounds of trains traveling nearby. They began making paintings of trains and building simple representations of trains with the Hill blocks.

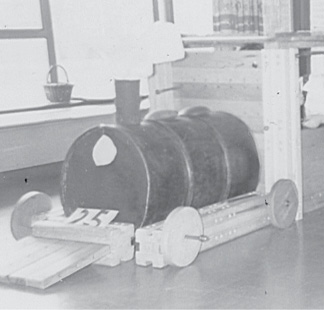

As their knowledge and experience grew, they worked together to build a train they would use for dramatic play for several weeks. Photographs show that the trains built with the Hill blocks varied from year to year. Sometimes, children built steam locomotives; other times, diesel engines. They added passenger cars, lounge cars, and dining cars, all constructed as accurately as possible with the Hill blocks. Some years there were crossing gates, crossing signs, and signal lights. They built a station ticket window from the blocks and made the tickets and the money to buy the tickets using construction paper and crayons. They even learned what the whistle signals meant. As Kirby noted, “During conversation and story time, we stop and listen whenever a train whistles. It is easy to hear them even far away when we are train minded, and it proves trains are real and all around us” (1950).

Children took on the many roles involved in train travel, taking turns being the engineer, the conductor, the brakeman, and even passengers. A conductor would call out “all aboard” and punch tickets. As many as 10 to 12 children were often involved in the various roles of collaborative play. Their play clearly fulfilled Hill’s goal of “enacting vital social relationships” through engagement with the block constructions.

Kirby had the children document their learning by making books and collaborating on murals of freehand cuttings. Freehand cuttings were pictures similar to mosaics that the children made with construction paper. It was a common activity in the 1940s and 1950s. Their in-depth study of trains and play with the Hill blocks over four or more weeks gave the children the deep knowledge needed for accurate representations. They knew about the form and function of the elements that made a train as well as what went with it—track, signals, and more. The freehand cutting books and murals were used “to help children organize their thinking; to clarify concepts and provide the opportunity for referring to pictures and books for accurate information (research)” (Kirby, n.d. b).

Kirby’s ability to guide children in learning about the details of the jobs, equipment, and materials associated with railroads gave the children a much deeper understanding of the familiar world of train travel.

Look Up! It’s a Plane: A Springtime Unit on Air Travel and Transportation

Accurate aviation information and vocabulary used with the children during the airplane unit in explaining pictures and in conversation help with the dramatic play.

—Betty Kirby

Kirby describes the beginning of an airplane unit in 1954 as follows:

While playing outdoors with kites, the children notice the many planes flying over the school. We begin talking about planes and the nearby airport. They build simple little planes from blocks. The children sat in these and played alone or in groups of two or three all over the kindergarten floor. Ed [custodian] brought in a three-sided wallboard tower that had been discarded by the scouts [who met at the school]. The children put a set of steps in the tower and began to play control tower with their block planes.

Because the children were not as familiar with airplanes as they were with trains, Kirby offered different experiences and materials so that they learned more about air travel before constructing an airplane and airport with the Hill blocks for sustained play. She filled the library table with plane and airport books and mounted photographs of many types of planes onto the walls for “reference, research, and study” (Kirby 1954). She sent information to families suggesting nearby locations to see planes. Kirby encouraged the children and families to bring in photographs of planes from magazines and newspapers for study.

Children’s knowledge about parts of planes, the jobs of people who work with planes, and what happens at airports increased through questions about planes flying overhead, pictures, experiences, and stories. They enlarged their dramatic play area and added equipment. The children learned from their research and the many small planes they built about the essential elements of planes. Using that information, they constructed a large, accurate plane with the Hill blocks to stand beside the terminal they had built for ongoing play (Kirby, n.d. d; Kirby, n.d. e). They covered their constructions with paper and painted them to make them look more realistic.

Children’s knowledge about parts of planes, the jobs of people who work with planes, and what happens at airports increased through questions about planes flying overhead, pictures, experiences, and stories. They enlarged their dramatic play area and added equipment. The children learned from their research and the many small planes they built about the essential elements of planes. Using that information, they constructed a large, accurate plane with the Hill blocks to stand beside the terminal they had built for ongoing play (Kirby, n.d. d; Kirby, n.d. e). They covered their constructions with paper and painted them to make them look more realistic.

By spring, the children were comfortable with the resources available to them in the classroom. Kirby noted that “some children go to the workbench to attach wooden spools to a board to make a control panel. The children use strips of fabric to make safety belts and add navigation lights with colored construction paper” (Kirby 1954). Their dramatic play begins to incorporate the vocabulary and the accurate information gained throughout the unit as they assume the duties of ground crew, pilots, copilots, stewardesses, passengers, ticket clerks, and mechanics. Kirby noted that she added posters, photographs, and books about planes to the “airport waiting room” to further support the idea of reference, research, and study. The children even learned to identify the planes flying overhead from the photographs on the wall (Kirby, n.d. e).

Once again, the children concluded their study of airplanes by creating individual construction paper cut-out books of things they knew to be true about planes. Photographs of Kirby’s classroom document the airport and plane built from Hill blocks during the springtime unit, while photographs of the wintertime train study show just a ticket booth as the only structure used to support play. The photographs from the plane study exemplify how the children grew in their ability to create a setting for more complex play.

Ongoing Adventures

This is a year of [their] life and not just a time to get ready to live.

—Betty Kirby

Throughout her career, Kirby varied how the kindergarten children concluded the year. As noted in the opening vignette, they often did a unit on boats, as Chicago was a major route for large ships. Other years, they learned about riding stables at a nearby park and built their own stable with four stalls and a simple corral. They used the classroom workbench to build horses to ride. A major unit during her final years of teaching involved using the Hill blocks to create a shopping center with a snack shop, theater, and supermarket. It was a long journey from the fruit and vegetable market in her early years of teaching and was indicative of her lifelong commitment to helping children explore and understand their world through, as Patty Smith Hill wrote, “the dramatization of the activities of human beings in vital social relationships” (quoted in Sherwood & Freshwater 2013, 165).

What Can Early Childhood Educators Learn from Betty Kirby’s Teaching?

Kirby viewed children as competent individuals capable of rich and complex learning. Her teaching back then echoes some of the key practices and current thinking about developmentally appropriate practice today (NAEYC 2020). She guided children in building—both literally and intellectually—on their prior knowledge and experiences outside of school in order to learn more. She believed that accurate information and rich vocabulary supported dramatic play and meaningful learning. Kirby taught children that paying attention to details was worthwhile and made play more interesting.

While we no longer have Hill blocks, we can follow Kirby’s lead and make what we need as we help children learn. A dramatic play area can become a fire station with a fire truck made of boxes. Children can go beyond fire hats, coats, and hoses and use cardboard to make the many tools firefighters have. They can learn about and use accurate “firefighter vocabulary” in their play. Their play can be transformed with new knowledge. Pre-K, kindergarten, and primary-grade children can engage in many kinds of rich, complex, long-term investigations to connect with the world around them. This will allow children to “live fully and well” as they meet curriculum standards in ways that include them as curriculum builders learning about their world.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Cuffaro, H.K. 1999. “A View of Materials as the Texts of the Early Childhood Curriculum.” In Issues in Early Childhood Curriculum, eds. B. Spodek & O.N. Saracho, 64–85. Troy, NY: Educators International Press.

Kirby, M.E. n.d. a. “Boats.” Curriculum notes, Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. n.d. b. “Typical Kindergarten Program.” Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. n.d. c. “Goals for Each Kindergarten Child.” Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. n.d. d. “Photograph Collection.” Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. n.d. e. “Unpublished Notes and Ephemera.” Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. 1950. “Train Unit.” Curriculum notes, Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. 1954. “May Plans 1954 Planes.” Curriculum notes, Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

Kirby, M.E. 1957. “April Plans 1957 Planes.” Curriculum notes, Margaret Elizabeth Kirby Papers, private collection.

National College of Education. 1932. Curriculum Records of the Children’s School. Evanston, IL.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/developmentally-appropriate-practice.

Sherwood, E., & A. Freshwater. 2013. “Patty Smith Hill and the Case Study of Betty Kirby.” In The Hidden History of Early Childhood Education, ed. B. Hinitz, 159-180. New York: Routledge.

Snyder, A. 1972. Dauntless Women in Education, 1856–1931. Washington, DC: Association for Childhood Education International.

Elizabeth A. Sherwood, EdD, is a professor in early childhood education at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. She teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in inquiry learning, curriculum approaches, and science education. She has written for numerous publications about early childhood science and the history of early childhood education. Betty Kirby was Elizabeth A. Sherwood’s aunt. [email protected]