Digital Stories in Palestinian and US Preschools: A Cross-Cultural Inquiry Project (Voices)

You are here

Digital Texts in the US and Palestine: Introduction to Majida Dajani and Daniel Meier’s article | Barbara Henderson, Voices executive Editor

This article on digital storybooks used in early childhood settings provides an international collaboration comparing teachers’ and children’s interactions in two cultural settings. Both Majida Dajani and Daniel Meier are teacher educators who utilize teacher research approaches, so their piece keeps the reader very close to classrooms and teaching practices. It also demonstrates a beautiful ear for amplifying teachers’ and children’s voices.

Dajani’s work as a teacher educator in Jerusalem and the West Bank provides a model in the field for innovative and effective literacy practices. Within the article, she describes her work with a large number of early childhood education practitioners at a range of sites. Her examples show how the teachers—none of whom was familiar with digital texts—came to use this technological tool to provide children with a more playful and child-centered literacy approach.

In contrast, Meier, a longtime teacher educator from California, describes his work developing teaching relationships with one group of young children. Devoting himself to meaningful levels of volunteer work at early childhood sites has been his practice throughout his career. By embedding himself within the field and maintaining part of his identity as a teacher of young children, he remains grounded in current classroom practice and close to evolving school environments and children’s learning needs.

For Dajani and Meier, this international collaboration allows each of them to examine their own cultural setting through the eyes of their coauthor from opposite sides of the globe. At the same time, the cross-site analysis of their classroom data builds sophisticated analytic categories that examine how and why teachers can use digital texts to enhance children’s control, choice, and enjoyment in their literacy education. This kind of triangulation of rich data sources is the hallmark of high-quality teacher research in the qualitative tradition. Dajani and Meier’s international collaboration provides readers with new ideas for designing and embarking on their own inquiry projects, perhaps even with colleagues at the global level.

Young children from under-resourced communities in the United States and in Jerusalem and the West Bank continue to be viewed from a deficit perspective concerning print and digital literacy learning. In selected research and policy, these children are too often viewed as lacking proficiency in print or digital technologies and lacking the requisite baseline skills and knowledge to engage with high-quality, engaging literacy education. In turn, they are denied pedagogical opportunities with both print and digital technologies that speak to their cultural, communal, and personal talents, interests, and abilities.

Young children from under-resourced communities in the United States and in Jerusalem and the West Bank continue to be viewed from a deficit perspective concerning print and digital literacy learning. In selected research and policy, these children are too often viewed as lacking proficiency in print or digital technologies and lacking the requisite baseline skills and knowledge to engage with high-quality, engaging literacy education. In turn, they are denied pedagogical opportunities with both print and digital technologies that speak to their cultural, communal, and personal talents, interests, and abilities.

In the US, children from immigrant and multilingual communities are most likely to experience classroom technologies and media that incorporate repetitive, low-level literacy skills and primarily teacher-directed instruction. This contrasts with recent guidelines about advancing equity and developmentally appropriate practice for each and every child (NAEYC 2019, 2020). Even though early childhood policy documents and initiatives advocate for intentionally integrating technology with children’s play and developmentally appropriate practice, results have been mixed (NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media 2012; DE & HHS 2016).

Palestinian early childhood education continues to confront a set of difficult political, economic, and educational challenges. While the current Palestinian Education Sector Strategic Plan 2017–2022 has placed increased emphasis on employing digital technologies in K–12 Palestinian classrooms, the available digital resources primarily resemble traditional paper and print books and promote teacher-centered instruction. Palestinian education also faces the additional challenge of addressing “digital space and identity for a community and culture with severely constrained physical space and physical identity” (Traxler et al. 2019, 4).

In 2014, Majida and Daniel met through a mutual Palestinian colleague. The inquiry project we report on in this article marks our second collaborative work (Dajani & Meier 2018). For this yearlong joint project, we examined the novel introduction of digital texts to US and Palestinian classrooms with no history of digital technology resources or teaching. For the purposes of this project, we define digital texts as the use of video and electronic platforms using digitized books (such as ebooks and audiobooks) in multiple languages and facilitated by adults in classrooms for the purpose of augmenting traditional print books. Our goal was to examine how these texts might provide a complementary pathway for meaningful literacy engagement through increased student interest, control, and choice. We also were curious to see if children would experience an additional sense of pleasure and joy in their learning if they took on more control of their literacy learning through digital texts.

Digital Texts: A Review of the Literature

Digital texts are increasingly common in homes and early learning programs and schools. Researchers and practitioners have found both challenges and benefits connected to their presence and use in these settings. Digital texts are most problematic when children have few opportunities to link engaging stories with their peers and adults in meaningful discussion, social interaction, and literacy-related activities (Vasquez & Felderman 2012; Hinostroza 2018). But when digital texts are both well-designed and thoughtfully implemented, they can support children’s literacy development by promoting

- multimodal, active, and engaged learning (Lisenbee & Ford 2017; Rohlfing & Müller-Brauers 2020) and visual processing (Moody, Justice, & Cabell 2010)

- vocabulary knowledge (Gremmen, Molenaar, & Teepe 2016; Strouse & Ganea 2017) and children’s conversations (Kosara & Mackinlay 2013)

- story comprehension (Takacs, Swart & Bus 2015) and knowledge of story elements (Robin 2008)

(To read more about effective features in digital texts, see Smeda, Dakich, & Sharda 2014 and Bikowski & Casal 2018.)

Children especially benefit from engaging with digital texts that encourage playful opportunities and occur within the broader frame of developmentally appropriate and equitable practices (NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center 2012; NAEYC 2016, 2019, 2020). Evidence also underscores the important role that adult guidance and instruction can play in influencing how children interact with digital texts and the extent to which they learn from them (Korat, Segal-Drori, & Klein 2009).

Methodology

Our project utilized practitioner inquiry, whereby teachers view themselves as experts on their own teaching and develop their own local knowledge of effective instruction (Castle 2012). Teacher inquiry involves a systematic process for educators to engage in a collaborative, cyclical process of observation, documentation, and reflection (Johanson & Kuh 2013; Johnston, Hadley, & Waniganayake 2020). One of its central goals is making visible children’s talents, interests, and capabilities and highlighting how educators are researchers who improve practice through inquiry, documentation, and reflection (Cochran-Smith & Donnell 2006; Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2012). Prominent approaches to collaborative early childhood teacher inquiry can be found in New Zealand (Carr & Lee 2012), the Reggio Emilia schools in Northern Italy (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2012), and a range of other international contexts (Kroll & Meier 2015).

For our project, we specifically examined the extent to which children took the lead in selecting digital texts, talking with each other and with adults about the texts, and choosing to engage in more playful, pleasurable, and artistic story-related activities. Central inquiry questions included

-

How can digital stories promote children’s choice and initiative taking in their literacy learning?

-

How can digital stories promote playful, pleasurable, and artistic opportunities for meaningful literacy engagement?

Setting and Participants

Daniel had no prior experience working with digital texts in classrooms, and digital texts had never been used in the US classroom chosen for this project. Majida also had no prior experience working with teachers using digital texts, nor had any of the Palestinian teachers involved in the project.

In the project’s Palestinian preschools, Majida took on the role of a teacher inquirer and collaborated with 10 teachers in 10 different kindergarten classrooms in Jerusalem and the West Bank. In terms of children’s ages, Palestinian kindergartens are the equivalent of US preschools. Like many of their US counterparts, they are situated in their own standalone settings and have a curriculum separate from that found in elementary schools.

A total of 254 children (103 males and 151 females) participated across the 10 classrooms. A total of 33 Arabic storytelling sessions were conducted in each of the classes, with three sessions devoted to each of 11 digital texts. Arabic was the language of instruction in all of the classrooms; digital texts came from the publicly available Asafeer website (http://3asafeer.com). Asafeer is a free site designed to help teach children, preschool through second grade, to read. It classifies books according to their level of difficulty.

In the United States, Daniel worked as a practitioner inquirer with one class of preschoolers in a public school district in the San Francisco Bay area. This is a school where Daniel has worked both as a part-time literacy teacher and as a volunteer over the past 20 years. In consultation with the head teacher, Daniel conducted whole-class read alouds of high-quality children’s literature, then worked with small groups of children to discuss the same read-aloud books as well as the introduction of digital texts. He also supported the children as they drew and dictated in personal journals. (For a more complete account of Daniel’s work in this classroom, see Meier 2020.)

The majority of the children in Daniel’s class were of Latino/a descent. Other children were of African American and Asian heritages. The digital texts were selected from a privately created platform that provided access to high-quality digital stories written in English by a range of international authors and illustrators. The platform was created by Dror Matalon, a software developer interested in testing the platform as a way to introduce digital texts from around the world to young children. Over the course of this project, Daniel and Dror often worked together in the classroom: Daniel worked with small groups of children with both print and digital stories, and Dror observed children as they interacted with the digital platform. The two often compared notes on the platform’s ease of use and fine-tuned its features to improve children’s access and engagement with the books.

Documentation and Data Analysis

Documentation and Data Analysis

Both Daniel and Majida worked in their respective classrooms for an entire year. During that time, we documented children’s initiative taking and decision making as emerging agentic learners (Adair 2014; Moore & Adair 2015; Adair, Colegrove, & McManus 2018; Yoon & Templeton 2019). We relied on Adair, Colegrove, and McManus’s definition of agency as “the ability for students to influence or make decisions about how and what they learn so as to expand their capabilities” (3).

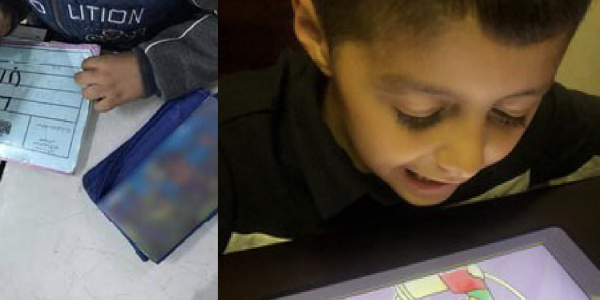

Majida employed classroom observation to observe teachers’ use of digital texts and the children’s interactions, discussions, and activities related to them. She documented these data sources through written observational notes and photographs, as well as through collecting children’s drawings and dictation and conducting informal interviews with teachers. Daniel used observational notes, photographs, and audio recordings to document his whole-group read alouds of print books, as well as the children’s discussions when they shared digital stories in small groups. Daniel also regularly collected children’s drawings and dictations from their personal journals, noting the date of each entry and any additional notes about particular comments and actions from each child.

As an international inquiry partnership, we also wrote analytical data memos (Saldaña 2021) on our own, then compared our memos with each other to reflect on patterns both within and across each international context. We collaboratively reviewed our observational notes, audio transcripts, and children’s art samples by coding for evidence of increased children’s initiative taking, playfulness, and pleasure in their digital story engagement. We utilized in vivo coding, which involves looking for verbatim language such as key words and phrases that we felt illustrated important ideas and actions from both the children and teachers. We also used emotion coding, which involves noting emotions both displayed by the participants and inferred from data from our perspectives as co-inquirers. We then held collaborative analyses sessions to theme the data by looking for patterns across the in vivo and emotion codes. (For a complete discussion of this coding and themeing, see Saldaña 2021.)

Questions to Ask when Evaluating Digital Texts

- Can the digital story be used across the curriculum?

- Is there ample potential in the digital story for rich dialogue, conversation, and interaction to promote agency?

- Is the story rich in language, including vocabulary, rhyming words, sight words, synonyms, and antonyms?

- Does the story pique children’s curiosity and invite them to explore different issues?

- Can the story create empathy to facilitate children’s understanding of shared values and social relations?

Findings

Based on our analysis of classroom observations, three themes emerged:

- an expanding awareness of engaging digital texts

- an increased playfulness and creativity with early literacy learning

- a new sense of artistry and sense of aesthetics

A discussion of each follows.

Expanding Awareness

The introduction of digital texts in both Palestine and the US created a way for teachers to use digital texts as additional literacy pathways and for children to gain greater control, choice, joy, and pleasure in their early literacy engagement.

Palestinian Context

In introductory sessions with teachers on conceptualizing the introduction of digital texts into the existing literacy curriculum, Majida collaborated with them to brainstorm instructional ideas based on several prompts. (See “Questions to Ask When Evaluating Digital Texts,” above.) For teachers new to the inquiry process and to digital stories, these planning sessions introduced foundational ideas for inquiry, documentation, and reflection. They also emphasized the value of intentionality in the selection of high-quality digital texts to motivate children to own their learning processes individually and with peers.

For example, Majida and the teachers chose the digital story Listening to My Body, by Gabi Garcia, for its engaging and interactive storyline, versatility in teaching varied science themes, promotion of phonemic awareness, and rich Arabic vocabulary and rhyming words. After sharing this digital story with the children, one teacher reflected, “Learning to make smart, thoughtful decisions about digital stories and their pedagogical value is an important skill for teachers.”

US Context

In the US classroom, Daniel discovered how digital stories featuring high-quality international children’s literature can expand content, language, and familiar visuals for young children. The digital texts provided a new, expanded international portrait of a variety of child, family, and community routines, adventures, and story scenarios. Similar to those used in the Palestinian context, these digital stories contained rich and varied vocabulary words and concepts. For instance, in Akai’s Special Mat, by Ursula Nafula, the young girl Akai searches for her “grandmother’s manyatta” and sits under an “edome tree.” These terms prompted Daniel and the children to discuss what a manyatta and an edome tree look like and how they contrast with the homes and trees familiar to the children.

Second, the digital texts depicted intergenerational relationships that prompted children to make connections to their own families and to reflect on how their families interact and work together on household tasks. In Grandma’s Bananas, by Ursula Nafula, the granddaughter learns the secret to how her grandmother ripens bananas and cassava for selling at the market. This led to a discussion between Daniel and the children on the relationship between the grandmother and granddaughter, the special time they spent together, and how this connects with the children’s own family relationships.

Increased Playfulness and Creativity

Najah, a Palestinian teacher, engages children in a read aloud of the digital version of A Rainbow of My Own, by Don Freeman and translated by Wia’m Ahmad. In this book, a child sees a rainbow from his window and runs outside to catch it. Before she begins the digital story, Najah asks the children what they think it will be about, if they have ever seen a rainbow, and what they know about rainbows. While reading, she asks a range of prompts to stimulate the children’s thinking and group dialogue:

Najah: How will the boy catch the rainbow?

Children: By the hand of his father . . . By using a ladder . . . By going to the flower garden.

Najah: What does the boy do before he goes outside?

Children: Puts on his raincoat, hat, and boots.

Najah: Why does he put on his raincoat, hat, and boots?

Children: It is cold, rainy . . . He puts on his raincoat, hat, and boots to protect himself . . . To be ready to catch the rainbow . . . He always puts on his raincoat, hat, and boots when he goes out.

After sharing the digital story, Najah implements various teacher-guided activities that also involve playful learning. She points out the letter “Raa” in Arabic (R in English) since it appears in all of the words related to the rainbow’s colors. She points out how the letter R can appear at the beginning, middle, or end of a word. Children are encouraged to think of other words containing R from digital texts that were read earlier. They then play the game of thumbs up (if R is in the word) and thumbs down (if R is not in the word), and they trace the letter (ر). Najah takes advantage of the digital text’s visuals and sounds, as well as the motor movements associated with certain prompts, to encourage children to act out specific elements of the story.

Palestinian Context

Palestinian Context

As seen in the vignette, digital texts enabled teachers to step back from their traditional, teacher-directed roles by helping children understand the meaning of the stories within the existing literacy curriculum. The digital stories gave children a new measure of control and choice because they were encouraged to choose and read their favorite texts as many times as they wished. As the sole authority controlling story selection and access, this enabled the children to assume some of the teachers’ roles. Once teachers realized their children’s newfound capabilities in using the platform and their increased agency in selecting the stories, they were more likely to stand back, observe, and adopt a more playful and curious stance—both toward the texts and the children’s literacy and social engagement.

For example, at one table, children collaborated on drawing a character from the story. At a second table, children brainstormed together to suggest a new title for the story. Children also mimed (or drew) part of the story while others tried to guess which story it was. During these child-directed activities, teachers used general prompts like “Remember to share with your peers” and “Work and think together.” If children had difficulty interacting with peers, teachers discussed together the steps they could take to involve these children more effectively.

Although not all 10 Palestinian classrooms reached the same level of integration, all the teachers combined traditional teacher-led instruction with newly conceptualized child-centered activities and discussions. A key strategy in this process was to use leveled questions to promote story comprehension before, during, and after digital text reading—both with the whole class and in small groups. Leveled questions addressed basic story elements (who, what, where, when, how, and why) and also utilized certain concepts, such as past (“did”), possibility (“can”), probability (“would”), prediction (“will”), and imagination (“might”). Because the digital format combines voice, image, and print, teachers were able to stimulate children’s thinking and dialogue about the text.

US Context

Daniel worked with small, mixed-age groups of children. He combined direct teacher support with child-centered, playful strategies to enhance digital story comprehension and engagement. The digital platform gave children a new sense of individual and collective control in selecting their favored digital texts without always involving an adult for direction or intervention. This child-centered control occurred in four distinct ways:

- Children themselves selected stories for the group to read and listen to from the platform’s selection of over 75 books. Children could control the computer’s trackpad and scroll through the easily recognizable visuals of book covers. As they did so, they often spontaneously discussed favorite books that they wanted to read together. The platform’s images of all the books in one window allowed the children to quickly scroll down the screen to see all the book covers, which let them preview the books more quickly than the physical collection of print books in their classroom library.

- Each child who wanted to act as the reader for their small group activated the digital text by clicking on the computer’s trackpad to “turn” the story’s pages. This interactional format offered a motivating measure of child control and physical involvement not found during more traditional, teacher-led read alouds with conventional print books. The electronic platform also allowed Daniel to ask the child acting as reader to pause the digitally read story at any point so that Daniel or any of the children could highlight and discuss a specific story element, word, phrase, or visual. The digital texts expanded children’s repertoire of how they interacted with the stories.

- Since a computer-generated voice “read” the book, Daniel and the children were freer to speak over the narration to refer to story elements and actions or to make a connection to children’s interests and experiences. Similarly, children had greater freedom to talk over the computer-generated voice without interrupting the (absent) traditional adult reader. This provided a new kind of layering of discourse and social interaction not afforded by traditional teacher-controlled read alouds of print books.

- The computer-generated narration helped both Daniel and Majida support children’s interests in dramatizing certain aspects of the digital texts. This provided a playful, pleasurable, artistic, and memorable experience. For example, in Tortoise Finds His Home, by Maya Fowler, Katrin Coetzer, and Damian Gibbs, a tortoise searches for his house and befriends several animals who climb onto his shell and join the search. Daniel drew on the multimodal features of the digital text to talk over the digital narration, encouraging children to act out specific elements of the story together. When the digital voice read “He looked into the distance and squinted at the grass,” Daniel (hands freed from not having to hold a printed book) asked the children to slightly cup their hands above their eyes to shield the sun and squint. As the tortoise met a snail, a sparrow, a ladybird, and finally a mouse, the children and Daniel heralded the arrival of each animal by dramatizing certain traits in unison.

A New Sense of Artistry

The digital stories that became beloved favorites were most effective at expanding the children’s aesthetic engagement.

Palestinian Context

The Palestinian teachers learned to emphasize a new sense of artistic playfulness with digital texts by introducing open-ended, arts-based activities. They created new story scenarios based on prompts such as “What if . . . ” and “Imagine if . . . ” Children extended their engagement with the digital stories through art (drawing, coloring), drama (playing roles, miming), playful movements (clapping the syllables of some words), and music (rhyming words). For example, playing the character of Tamtoum from Tamtoum (https://3asafeer.com), one child explained that he had to shout loudly to express the character’s anger. When compared with the static illustrations in traditional storybooks, this shows how repeatedly reading and listening to digital stories can facilitate multimodal responses to and learning from the stories.

Children benefit from engaging with digital texts that encourage playful opportunities and occur within the broader frame of developmentally appropriate and equitable practices.

US Context

In the US classroom, children used personal journals to draw and dictate the connections they made to stories. From earlier work with Daniel using conventional print books, they had learned that they could use a metal clip to secure pages so that everyone in a small group could see a page for drawing. The digital story platform enabled the child reader to control when and how to return to a favorite page in the digital text and to invite classmates to look at one or more illustrations for their drawing and dictation. Their collective interest in drawing helped the children understand, interact with, and revisit the digital stories in a shared, communal manner that reinforced both literary and social connections on the children’s own terms.

Many of the children eagerly engaged with digital text illustrations for journal drawing and dictation. Sometimes, a single character captured a child’s interest, as in the following vignette.

Singing in the Rain, by Mala Kumar and Manisha Chaudhry, tells the story of a singer who meets a music-loving dinosaur. Four-year-old Brian wants to draw something about the dinosaur. This is Brian’s first time working in his personal journal, so Daniel helps him ease into the activity. After reading the digital story, Daniel advances it until Brian selects an illustration.

“I don’t know what to draw,” he says.

Daniel suggests that Brian draw the eyes. Brian does, then says he wants to draw the scales. Daniel holds Brian’s hand and slowly guides the marker for him. “Up down, up down, up down makes the scales,” Daniel says.

While Brian could have carried out the same drawing and dictation activity with a print book, this particular digital text holds special interest for him. The other children love interacting with the story on the platform, and Brian wants to share that communal enjoyment in an artistic way.

Interpreting Findings in Both Contexts

Our one-year qualitative research project indicates that digital stories can promote new pedagogical space for increased child agency and a sense of playfulness and pleasure in literacy learning (Genishi & Dyson 2015). In both the US and Palestinian settings, digital texts increased access to an expanded repertoire of high-quality children’s books and varied characters, settings, content, vocabulary, and literary language. With this increased access, children selected and revisited stories on their own social and intellectual terms and added a new layer of child-initiation and control to their literacy experiences.

Digital texts enabled teachers to step back from traditional roles by helping children understand the meaning of the stories within the existing literacy curriculum.

This contrasts with the time-honored routine in Palestine, the US, and many other global contexts of teachers controlling the transmission and interpretation of story content, discourse, visuals, and interpretation. In these instances, children are often passive recipients of teachers’ oral reading, and they lack access to multiple modalities to broaden and deepen their physical, social, cognitive, and aesthetic engagement with stories.

In addition, the multimodal capabilities of digital stories encourage children to take on new, more active roles as the selectors and readers of texts. They also promote new forms of adult-to-child and child-to-child interaction and discourse. For instance, the ability for teachers to talk over digital narration provides more pedagogical space for teachers and children to converse about a story and with each other. Children sense there is no risk of interrupting a teacher because the teacher no longer serves as a traditional keeper of reading and narration. By pausing or stopping a story at will, the interactional parameters are expanded and encourage more and different forms of story engagement and discourse. Both teachers and children can try on new roles as more equal co-constructors of language, discourse, and games.

Next Steps for Teachers

Next Steps for Teachers

The sense of playfulness, meaning, and pleasure that digital texts provide are elements often omitted in literacy policy and curriculum for children from under-resourced communities globally.

Based on this project, we recommend the following next steps for teachers and those who support their development:

- Introduce the use of digital texts in preservice teacher education and in-service professional development. In light of COVID-19’s global persistence and the possibility of a return to full or partial remote learning, teachers need early exposure to both the challenges and benefits of digital stories on varied platforms.

- Create new avenues for cross-cultural and cross-professional dialogue about how digital texts can be used with children and families. We encourage educators to share digital platforms for exchanging inquiry-based data and to collaborate within inquiry group formats both locally and internationally.

- Utilize inquiry tools to integrate traditional teacher-directed instruction with child-centered and discovery-based literacy practices involving digital texts. We recommend educators seek administrative support for the time they need to plan and collaborate on integrating teacher inquiry around curriculum and assessment. (See the professional process of melding inquiry groups and learning stories as described in Escamilla et al. 2021. This text provides resources for starting inquiry groups.)

- Discuss and share inquiry-based data from digital texts in both home and school settings and critique their use via recent NAEYC position statements on developmentally appropriate practice and equity and anti-bias education

-

Consider engaging in cross-cultural professional connections with international colleagues by participating in internationally available webinars. These include

-

Educa

geteduca.com -

ChildCare Exchange

childcareexchange.com -

Reggio International

reggiochildren.it/en/loris-malaguzzi-international-centre

-

Educa

The international inquiry journey is both personally satisfying and provocative for one’s professional growth as curious adult learners across our entire careers.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- peruse an archive of Voices articles

- read the Fall 2021 Voices compilation

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teachers and children who participated in this study in both international contexts. We also thank Dror Matalon and Amro Abu Humaidan (https://3asafeer.com) for creating the electronic platforms used in our project.

Photographs: courtesy of Majida Dajani; © Getty Images

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Adair, J.K. 2014. “Agency and Expanding Capabilities in Early Grade Classrooms: What it Could Mean for Young Children.” Harvard Educational Review 84 (2): 217–241.

Adair, J.K., K.S.S. Colegrove, & M. McManus. 2018. “Troubling Messages: Agency and Learning in the Early Schooling Experiences of Children of Latina/o Immigrants.” Teachers College Record 20 (6): 1–40.

Bikowski, D., & J.E. Casal. 2018. “Interactive Digital Textbooks and Engagement: A Learning Strategies Framework.” Language Learning & Technology 22(1): 119-136.

Carr, M., & W. Lee. 2012. Learning Stories: Constructing Learner Identities in Early education. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Castle, K. 2012. Early Childhood Teacher Research: From Questions to Results. New York: Routledge.

Cochran-Smith, M., & K. Donnell. 2006. “Practitioner Inquiry: Blurring the Boundaries of Research and Practice.” In Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research, eds. J.L. Green, G. Camilli, & P.B. Elmore, 503–518. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Dajani, M. & D. Meier. 2018. “The Role of Narrative in Culturally Responsive Literacy Education: A Collaborative Project in US and Palestinian Preschools.” International Journal of Early Years Education 27 (3): 1–14.

DE, & HHS (US Department of Education and US Department of Health and Human Services). 2016. Early Learning and Educational Technology Policy Brief. Washington, DC: DE and HHS. https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/

Education Sector Strategic Plan 2017–2022: An Elaboration of the Education Development Strategic Plan III (2014-2019). 2017. Ramallah-Palestine: Ministry of Education and Higher Education.

Edwards, C., L. Gandini, & G. Forman, eds. 2012. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. 3rd ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Escamilla, I., L. Kroll, D. Meier, & A. White. 2021. Learning Stories and Teacher Inquiry Groups: Reimagining Teaching and Assessment in Early Childhood Education. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Genishi, C., & A.H. Dyson. 2015. Children, Language, and Literacy: Diverse Learners in Diverse Times. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gremmen, M.C., I. Molenaar, & R.C. Teepe. 2016. “Vocabulary Development at Home: A Multimedia Elaborated Picture Supporting Parent–Toddler Interaction.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 32 (6): 548–560.

Hinostroza, E.J. 2018. “New Challenges for ICT in Education Policies in Developing Countries: The Need to Account for the Widespread Use of ICT for Teaching and Learning Outside the School.” In ICT-Supported Innovations in Small Countries and Developing Regions, ed. I.A. Lubin, 99–119. New York: Springer International Publishing.

Johanson, S. & L. Kuh. 2013. “Critical Friends Groups in an Early Childhood Setting: Building a Culture of Collaboration.” Voices of Practitioners 8 (2): 1–16.

Johnston, K., F. Hadley, & M. Waniganayake. 2020. “Practitioner Inquiry as a Professional Learning Strategy to Support Technology Integration in Early Learning Centers: Building Understanding Through Rogoff’s Planes of Analysis.” Professional Development in Education 46 (1): 49–64.

Korat, O., O. Segal-Drori, & P. Klein. 2009. “Electronic and Printed Books with and Without Adult Support as Sustaining Emergent Literacy.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 41 (4): 453–475.

Kosara, R., & J. Mackinlay. 2013. “Storytelling: The Next Step for Visualization.” Computer 46 (5): 44–50.

Kroll, L.R., & D.R. Meier, eds. 2015. Educational Change in International Early Childhood Contexts: Crossing Borders of Reflection. New York: Routledge; Washington, DC: Association for Childhood International.

Lisenbee, P., & C. Ford. 2017. “Engaging Students in Traditional and Digital Storytelling to Make Connections Between Pedagogy and Children’s Experiences.” Early Childhood Education Journal 46 (1): 129–139.

Meier, D.R. 2020. Supporting Literacy for Children of Color: A Strength-Based Approach to Preschool Literacy. New York: Routledge.

Moody, A.K., L.M. Justice, & S.Q. Cabell. 2010. “Electronic Versus Traditional Storybooks: Relative Influence on Preschool Children’s Engagement and Communication.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 10 (3): 294–313.

Moore, H.C., & J.K. Adair. 2015. “‘I’m Just Playing iPad’: Comparing Prekindergartens’ and Preservice Teachers’ Social Interactions While Using Tablets for Learning.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 36 (4): 362–378.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children) & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media. 2012. “Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8.” Joint position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/ps_technology.pdf

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 1996. “Technology and Young Children Ages 3 Through 8.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity-position

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/dap-statement_0.pdf

Robin, B. 2008. “The Effective Uses of Digital Storytelling as a Teaching and Learning Tool.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy Through the Communicative and Visual Arts (vol. 2), ed. J. Flood, S. Heath, & D. Lapp, 429–440. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rohlfing, K., & C. Müller-Brauers C., eds. 2020. International Perspectives on Digital Media and Early Literacy: The Impact of Digital Devices on Learning, Language Acquisition and Social Interaction. New York: Routledge.

Saldaña, J. 2021. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Smeda, N., E. Dakich, & N. Sharda. 2014. “The Effectiveness of Digital Storytelling in the Classrooms: A Comprehensive Study.” Smart Learning Environments 1 (1): 6.

Strouse, G.A., & P.A. Ganea. 2017. “A Print Book Preference: Caregivers Report Higher Child Enjoyment and More Adult-Child Interactions when Reading Print than Electronic Books.” International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 12: 8–15.

Takacs, Z.K., E.K. Swart, & A.G. Bus. 2015. “Benefits and Pitfalls of Multimedia and Interactive Features in Technology-Enhanced Storybooks: A Meta-Analysis.” Review of Educational Research. 85 (4): 698–739.

Traxler, J., Z. Khaif, A. Nevill, S. Affouneh, S. Salha, A. Zuhd, & F. Trayek. 2019. “Living Under Occupation: Palestinian Teachers’ Experiences and Their Digital Responses.” Research in Learning Technology 27.

Yoon, H.S., & T.N. Templeton. 2019. “The Practice of Listening to Children: The Challenges of Hearing Children Out in an Adult-Regulated World.” Harvard Educational Review 89 (1): 55–84.

Vasquez, V.M., & C.B. Felderman. 2012. Technology and Critical Literacy in Early Childhood. New York: Routledge.

Majida “Mohammad Yousef” Dajani, PhD, is an assistant professor at Al-Zaytouna University of Science and Technology, a teacher educator, a researcher, and a trainer. Majida has worked on several early childhood education programs, including RTI and the Early Grade Reading Project. [email protected]

Daniel R. Meier, PhD, is professor of elementary education at San Francisco State University. His publications include Critical Issues in Infant-Toddler Language Development: Connecting Theory to Practice (editor), Supporting Literacies for Children of Color: A Strength-Based Approach to Preschool Literacy (author), and Learning Stories and Teacher Inquiry Groups: Reimagining Teaching and Assessment in Early Childhood Education (coauthor).