Toward Pro-Black Early Childhood Teacher Education

You are here

Authors’ Note

Decisions regarding whether to capitalize Black and white as related to race, ethnicity and culture continue to evolve. Many reputable publishing sources, including NAEYC, capitalize both Black and White. However, the authors of this piece standardize the capitalization of the “B” in Black in all our writing when referring to people of African descent and not the “W” in white. The rationale for this position is that Black refers to not just a color but signifies a history and the racial identity of Black Americans. We do not capitalize white as capitalizing the word follows the lead of white supremacists, and white people in general have much less shared history and culture and don’t have the experience of being discriminated against because of skin color. We also draw from the work of Touré that intentionally changed the capitalization of white since white Americans identify as Italian American, Irish, Polish, and so forth, whereas Black Americans are unable to trace their precise lineage due to centuries of institutional slavery (2006). Likewise, Davis lowercases white as “a political move to draw attention to the destructive nature of racism and white privilege in the US” (2019, 154).

Conversations about race and racism and teaching racial histories can and must happen with our youngest children if they are to grow into adults who will create more equitable tomorrows.

—Early Childhood Education Assembly, National Council of Teachers of English

Young children recognize race. They talk about it and appropriate racialized views of people around them during and beyond their earliest years (Roberts & Gelman 2016). Because anti-Blackness is the most dominant form of racism in the United States (Dumas & Ross 2016), children cannot avoid absorbing messages of white superiority and Black degradation (Escayg, Berman, & Royer 2017) as our society surrounds them with “messages that affirm the superiority of whites and the assumed inferiority of Black people, like smog in the air” (Tatum 1997, 6). For some children, these messages are transmitted through the overt racist words and actions of adults around them. However, most children learn about race in more insidious ways—through the absence, marginalization, or misrepresentation of Blackness in their daily lives (Miller 2015). This includes learning from media, children’s books, the demographics of family friends, white Sunday School classes, advertisements, and many other sources.

As early childhood educators, we have a fundamental responsibility to counter these anti-Black messages and to build awareness of how these messages are reiterated in schooling (Boutte & Bryan 2021). This means that the work of early childhood teacher educators is critically important as we engage with and mentor prospective and in-service teachers to impact the lives of young children. Our positions demand our recognition that being “polite” and silent about the needs of Black children contribute to endemic curricular, instructional, symbolic, linguistic, and systemic trauma for African American children (Boutte & Bryan 2021) and an educational system that sends the message of white superiority to all children.

We (the authors) are early childhood teacher educators who work together as an Anti-Racist Collective (ARC), which is a collective of five faculty members at the University of South Carolina Department of Instruction and Teacher Education focusing on equity and countering anti-Blackness in our teaching, research, and service. We collaborate with each other in the ongoing development of an urban education cohort of 25 to 28 teacher candidates within our preservice program (Wynter-Hoyte et al. 2019), and we work with pre-K–12 educators around the country. In this article, we share a few practices (of many) that we use to prepare preservice teachers as anti-racist, pro-Black educators. We organize this piece around two areas:

- confronting anti-Blackness with pro-Black pedagogy

- preservice teachers’ growth

Although we describe our work with preservice teachers, we do the same work with in-service teachers and therefore encourage teachers reading this article to consider implications for their own self-study and classroom transformation. In addition, we highlight insights, through the work of preservice teachers, for the day-to-day teaching of young children.

Confronting Anti-Blackness with Pro-Black Pedagogy in Teacher Education

For preservice teachers to be able to teach in pro-Black ways, they must be able to identify anti-Black racism in educational institutions (policies, practices, curricula) and in individual dispositions and actions. To be clear, pro-Black does not mean anti-white or anti-other ethnic groups (Boutte et al. 2021). It simply declares an unapologetic, positive, proactive perspective regarding Blackness and Black people. The reality is that those experiencing anti-Blackness and other “isms” rarely have the luxury to prepare for the encounter or the power to change racial realities. Therefore, on behalf of those who experience anti-Blackness and in the quest for a more comprehensive and inclusive education for all children, we ask teacher candidates to engage in introspection (examination of self and institutions), to relearn histories, and to apply their knowledge in the teaching of young children.

Readings and Videos

We typically spend several courses building teacher candidates’ theoretical, historical, and contemporary knowledge so they understand why pro-Black teaching is necessary. For example, to help them understand the urgent need to respond to the disparate experiences that Black children encounter in schools, we share research identifying oppressive practices such as the over-referral of Black students to special education (Morgan 2020), under-referral to gifted programs (Ford 2013), and disproportionately harsh disciplining when compared to white students as young as preschool (US ED OCR 2016).

We provide readings and videos about

- anti-Black violence children experience in schools (Boutte & Bryan 2021)

- the importance of relearning history through an anti-racist and pro-Black lens (Wynter-Hoyte & Smith 2020)

- classroom examples of pro-Black teaching (Baines, Tisdale, & Long 2018; Boutte 2016)

We make decisions about these resources based on our own study of the rich history of scholarship around anti- and pro-Blackness informed by generations of Black scholars such as Molefi Kete Asante, Asa Hilliard, Joyce King, and Carter G. Woodson. (See "Further Resources" below for lists of these and other professional resources.)

Critical School Memoirs

In a 2018 video, Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz suggests that educators who engage in anti-racist teaching begin with an “archaeology of self.” She sees this as a critical step in developing the ability to recognize and “interrupt situations and events that are motivated and upheld by racial inequity.” During this exploration, we remind candidates that they may experience discomfort, but that disequilibrium (anxiety, guilt, and doubt) can be an initial step in learning something new. Boutte calls this a critical “learning edge” and explains that “if you retreat at this point, you may lose the opportunity to expand your understanding,” reminding learners to persevere because of an expressed commitment to the education of children (2016, 5).

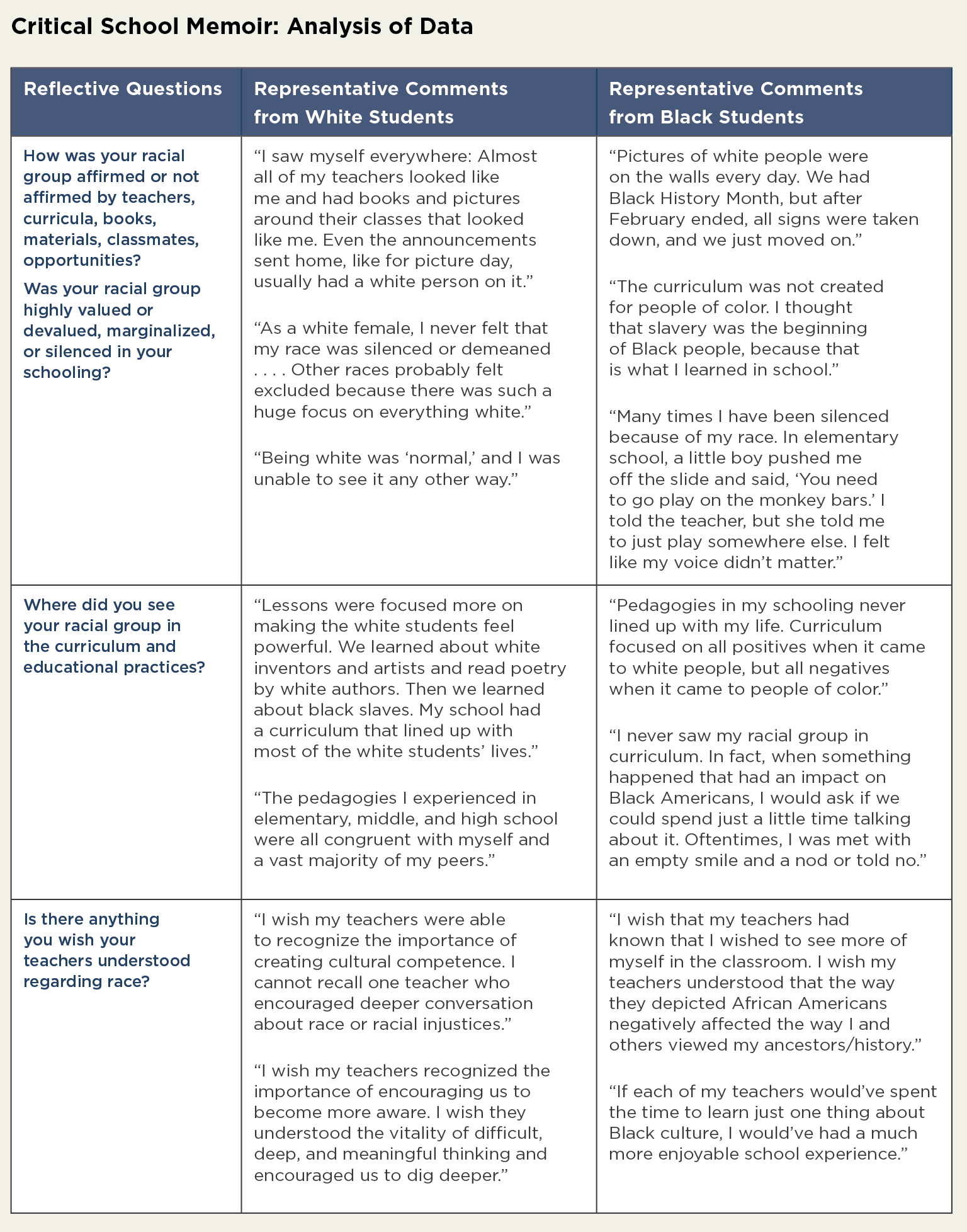

We use an assignment called Critical School Memoir as an entrée into the archaeology of self. Through it, we engage preservice educators in examining themselves and the institutions in which they were schooled as they learn to identify anti-Black racism. Building on an assignment originally developed by Tambra Jackson, we ask preservice teachers to examine messages received in their own schooling and to similarly engage someone from a racial background different from their own, and then to present those messages in a PowerPoint or class presentation. Focusing on a range of social identity factors (race, class, gender identification, sexual orientation, language), they and their interviewees take mental walks through the halls, classrooms, textbooks, and curricula of their own schooling. They also review school archives (news clippings, yearbooks, photos, websites), analyzing the dominance, marginalization, and absence of groups of people in these archives, and share these artifacts to illustrate the points in their presentations.

The preservice teachers share analyses of this experience in presentations that outline ways that schooling can affirm and thereby humanize students alongside ways it can oppress and dehumanize. Although powerful insights are gained across analysis of multiple forms of oppression, examinations of race are typically the most eye-opening. Our white teacher candidates tend to gain insights about racial realities that most have never considered, while Black teacher candidates often appreciate this as a space to make racial realities visible to their white peers and/or to examine their own learned and internalized negative views of Blackness. (See “Critical School Memoir: Analysis of Data” below for representative examples of these insights.)

Designing Pro-Black Curriculum

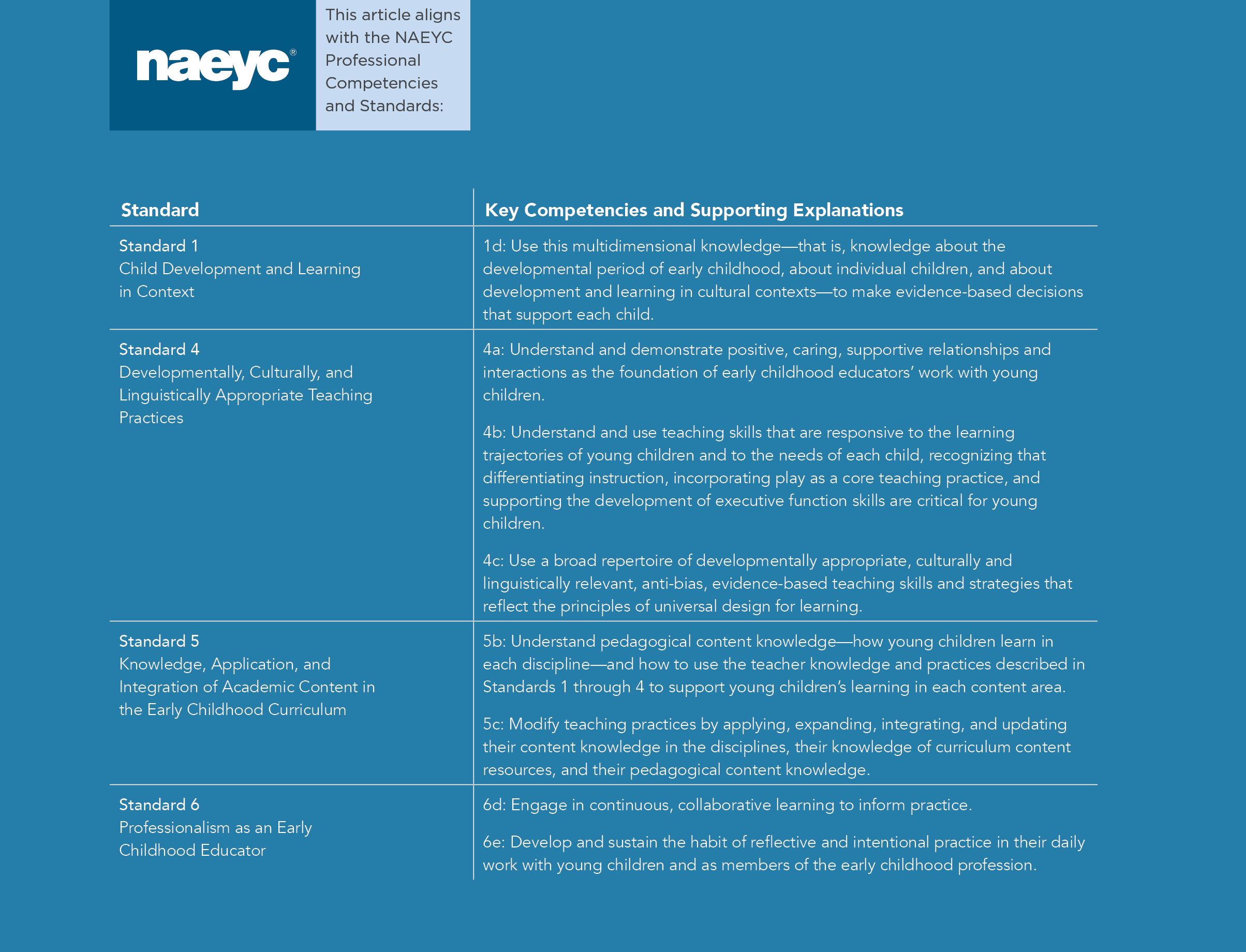

As teacher candidates develop the ability to identify anti-Blackness in themselves and their own schooling, they begin to understand more about the need for pro-Black curricula. To support that, we require them to create and teach pro-Black lessons to children in pre-K–grade three classrooms. While these lessons involve engaging preservice teachers in understanding and upholding NAEYC’s position statement on developmentally appropriate practice—specifically, the idea that curriculum should be “culturally and linguistically responsive” (2019, 26)—we go further by emphasizing specificity around race, an action that we see as critical for NAEYC and other organizations.

Thus, while a range of ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups are represented in these learning experiences, one set of lessons requires a focus on the African, African Diaspora, and African American contributions to the world’s knowledge (Wynter-Hoyte et al., in press). This focus on often hidden histories and people teaches counternarratives to the traditional and often negative and stereotypical depiction of Africans and African Americans. The goal is for preservice teachers to experience broadening white-dominant curricula by normalizing Black joy; that is, “the love, collegiality, and collectiveness that Black people have exhibited throughout history” (King 2020, 338) and the accomplishment, agency, and resistance of Black people.

An essential and required component of each lesson is the inclusion of criticality as teacher candidates engage children in thinking about why these elements have been left out of the curriculum and why it is essential to make these concepts foundational. By the end of their junior year, our students have developed a collection of over 25 lessons depicting hidden African, African Diaspora, and African American histories focused on mathematicians, scientists, inventors, explorers, artists, and more. Simultaneously, we engage in this work with in-service teachers who often become the candidates’ internship mentor teachers or coaching teachers. This collaboration means that a broad range of educators is able to challenge Eurocentric curricula, and many of those who graduate from our program do so with the ability and confidence to incorporate pro-Black teaching as foundational across the year.

Developing Pro-Black Book Collections

Key components in pro-Black pedagogy are the books that fill classrooms. Statistics continue to show that we have a long way to go to normalize books by Black authors and about Black people’s stories, languages, issues, and contributions (Fernando 2021). When working with future and current educators, we make the point that it is not enough to add a book or two about Africans to the classroom library. To truly normalize Blackness, there should be as many books about African and African descendant people as there are about Europeans and European Americans (Baines, Tisdale, & Long 2018). Across most courses, we introduce books weekly that honor Blackness. See "Further Resources" below for lists of such books, intended to support both preservice and in-service teachers.

Without considering the other elements of pro-Black pedagogy described throughout this article, it is easy for preservice and in-service teachers to think that, once they build a diverse book collection, they have engaged in pro-Black teaching. This is only one small element in countering anti-Blackness. To normalize Blackness, classrooms require rich representations throughout the day and the curriculum—in computer programs, songs, and music, using books and posters about Black architects in the block center, Black artists in the art center, Black inventors in the science center, and in books used as instructional texts and assessment.

Learning to Ask Critical Questions

Another foundational element in pro-Black pedagogy is the development of teachers’ and children’s critical eye. This means recognizing when voices and peoples are omitted, marginalized, degraded, or misrepresented and when other voices and peoples dominate and hold the power. Early childhood educators are aware of young children’s ability to discern fairness, injustice, and power—for example, when they ask “Why does my friend have more snacks?” or “Why does my classmate get to be line leader?” Yet few educators use the children’s keen understanding of equity in general as a bridge to conversations more specifically about racial equity (Baines, Tisdale, & Long 2018). Gloria Ladson-Billings (2017) refers to this as a critical consciousness and notes that it is the least utilized tenet in her culturally relevant approach to pedagogy. However, when a critical habit of mind becomes foundational in classrooms, children quickly learn to notice whose voices are prioritized, minimized, or absent in learning experiences, films, books, music, social media, local and world events, and even in their play (Kinard et al. 2021).

The following questions can help educators and children identify racial injustices and act for change—for example, writing letters to people who order classroom materials or, as did the kindergartners of one of our graduates, writing to police to express their concerns about the killing of Black people.

- Who are the people in this text? What roles do they play? Who is shown to be beautiful? Nice? Smart? Leaders? Important? Who is not? Is that fair? Why?

- Where do you see Black joy, beauty, and accomplishment?

- Do you see Black people treated fairly? Unfairly? How?

- How does the text make you feel? Other people? Why?

- Is there a need for change? What? How?

One way these questions can be introduced is by examining picture books such as The House That George Built, by Suzanne Slade. The book describes how George Washington built the White House, barely mentioning the significant role that enslaved Africans played in the building’s construction. In contrast, Charles R. Smith Jr.’s children’s book, Brick by Brick, provides a more historically accurate narrative. These types of texts encourage teachers and children to use critical questions to transform passive acceptance of messages of white superiority to rejection and action, which can be empowering for children (Muller 2021). Practicing with texts, children can then use critical questions to identify racial injustices in other settings, such as current events and other elements of school and community life.

Preservice Teachers’ Growth

The development of the preservice teachers’ abilities to recognize anti-Blackness and teach in pro-Black ways often involves changes in their outlooks on the world. Many in our program describe having never been asked to consider normalcy outside of white, Christian, middle class norms. One candidate’s words capture the feelings of many white students with whom we have worked:

I feel as if I came into the college with a very narrow, blinded view of life. I was so oblivious to all the hurt but also the beauty that was around me. [These courses have] broadened my perspective and helped me see the rich culture that is all around me. The cohort helped shape my views on race and racial issues.

Black students in our program frequently express that, while painful, they are grateful that race is an integral part of our program. On several occasions, after relationships were built as a result of these experiences, Black students explained to their peers just how life-and-death these issues are for anyone who will be teaching Black children.

Through this work, preservice teachers also come to appreciate young children’s abilities to identify racial injustice. As one student articulated, “I see that children are not as unaware as we think. Children are brilliant. . . . They understand inequality and fairness as well as power and race.” This understanding of young children’s abilities prepares preservice teachers to advocate for pro-Black teaching, not as a burden or to be checked off a list, but as a joyous pursuit in service of all children.

Toward Pro-Black Early Childhood Teacher Education

We believe in facilitating classrooms where children can “live part of their dreams within their educational spaces” (Freire & Macedo 1987, 127). However, school practices regularly hinder Black children from fully living their dreams and white children from being fully educated by not including Black knowledge and experience. While excellent pro-Black work is being done (Baines, Tisdale, & Long 2018; Jackson et al. 2021; Wynter-Hoyte et al. 2021), it is far from the norm and often implemented superficially as teachers proclaim: “I teach my children to love one another.” Professions of love do not constitute pro-Black teaching when they are not joined with attention to issues of power, oppression, marginalization, and misrepresentation. Pro-Black love involves what Pitts (2020) describes as “truth-telling.”

Through this work, preservice teachers also come to appreciate young children’s abilities to identify racial injustice.

Reflecting on what all of this means for developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) in early childhood classrooms and teacher education programs, we offer a loving critique for teachers, teacher educators, and the profession: Race should be at the forefront of planning, teaching, assessing, and reflecting to foster children’s development and learning across domains and across the curriculum. For instance, drawing from decades of research by Black scholars such as Asa Hilliard, Janice Hale, and Amos Wilson, we understand that Black children’s development in all five domains is influenced by children’s racial identities and contexts in significant ways (Broughton 2020; Boutte & Bryan 2021). It is essential to name race and its centrality to young children’s development in the United States.

Standing alongside the position statement on advancing equity and other foundational documents, the DAP framework (2020) continues to be generative—as it has been and should be. A discussion related to race is currently included within the position statement on DAP. For example, within Principle 1, there is an acknowledgment of “Black and Latino/a children, as well as children in refugee and immigrant families, children in some Asian American families, and children in Native American families, having been found to be more likely to experience ACEs [adverse childhood experiences] than white non-Latino/a and other Asian American populations of children (Sacks & Murphey 2018), reflecting a history of systemic inequities” (8). It also includes a discussion of the negative impacts of racism, such as the long-term effects of racial trauma. Yet these points could more explicitly inform early childhood educators’ practices, beliefs, and decisions—and the practices, beliefs, and decisions of the teacher educators who work with them—if they were listed as a principle in and of itself. Regardless, our goal is to call attention to these important points so that they are more explicitly understood by educators.

Standing alongside the position statement on advancing equity and other foundational documents, the DAP framework (2020) continues to be generative—as it has been and should be. A discussion related to race is currently included within the position statement on DAP. For example, within Principle 1, there is an acknowledgment of “Black and Latino/a children, as well as children in refugee and immigrant families, children in some Asian American families, and children in Native American families, having been found to be more likely to experience ACEs [adverse childhood experiences] than white non-Latino/a and other Asian American populations of children (Sacks & Murphey 2018), reflecting a history of systemic inequities” (8). It also includes a discussion of the negative impacts of racism, such as the long-term effects of racial trauma. Yet these points could more explicitly inform early childhood educators’ practices, beliefs, and decisions—and the practices, beliefs, and decisions of the teacher educators who work with them—if they were listed as a principle in and of itself. Regardless, our goal is to call attention to these important points so that they are more explicitly understood by educators.

Thus, as we prepare teacher candidates to think about addressing racial inequities through their teaching of young children, we challenge early childhood teacher educators to overturn the status quo by dismantling and rebuilding unjust systems. We offer questions for self-examination in support of that work:

- Do I take an unequivocal stand with my colleagues in support of identifying anti-Blackness and countering it through pro-Black teaching?

- Do I access a wide range of Black educators to inform my understandings of racial realities, history, literature, science, mathematics, and early childhood education?

- Do I regularly examine my attitudes and behaviors as they contribute to or combat anti-Blackness? Do I engage preservice and in-service teachers similarly?

- Do I build students’ understandings about Black joy, brilliance, and contribution and require them to use that knowledge as fundamental in early childhood classrooms?

We invite educators at all levels to engage in truth-telling love in the work to establish pro-Black teaching in early childhood classrooms and teacher education.

Further Resources

Check out the following resources for more information and further reading on how to incorporate pro-Black teachings into your classroom, with both young children and teacher candidates.

- This webpage lists a plethora of pro-Black children’s literature options: https://africandiasporaliteracy.weebly.com/childrens-literature.html

- This webpage, compiled by the authors, offers resources for families to engage in pro-Black, anti-racist discussions with their children using a variety of media: antiracistcollective.weebly.com/resources-for-families.html

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Baines, J., C. Tisdale, & S. Long. 2018. "We've Been Doing It Your Way Long Enough": Choosing the Culturally Relevant Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Boutte, G. 2016. Educating African American Students: And How are the Children? New York: Routledge.

Boutte, G., & N. Bryan. 2021. "When Will Black Children be Well? Interrupting Anti-Black Violence in Early Childhood Classrooms and Schools." Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 22 (2): 232–43.

Boutte, G., J.E. King, G.L. Johnson, Jr., & L. King. 2021. We Be Lovin’ Black Children: Learning to Be Literate About the African Diaspora. Gorham, ME: Myers Education Press.

Broughton, A. 2020. “Black Skin, White Theorists: Remembering Hidden Black Early Childhood Scholars.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood: 1–16.

Davis, S.M. 2019. “When Sistahs Support Sistahs: A Process of Supportive Communication About Racial Microaggressions Among Black Women.” Communication Monographs 86 (2): 133–157.

Dumas, M.J., & K.M. Ross. 2016. “ ‘Be Real Black for Me’ Imagining BlackCrit in Education.” Urban Education 51 (4): 415–42.

Escayg, K., R. Berman, & N. Royer. 2017. "Canadian Children and Race: Toward an Antiracism Analysis." Journal of Childhood Studies 42 (2): 10–21.

Early Childhood Education Assembly. 2015. “Race Talk in the Early Childhood Classroom”. National Council of Teachers of English. http://www.earlychildhoodeducationassembly.com/uploads/1/6/6/2/16621498/race_talk_in_the_early_childhood_classroom__1_.pdf

Ford, D.Y. 2013. Recruiting and Retaining Culturally Different Students in Gifted Education. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Fernando, C. 2021. Racial Diversity in Children’s Books Grows, but Slowly. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/race-and-ethnicity-wisconsin-madison-childrens-books-480e49bd32ef45e163d372201df163ee

Freire, P., & D. Macedo. 1987. Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Jackson, J., S.N. Collins, J.R. Baines, & V. Gibson. 2021. “Say It Loud—I’m Black and Proud: Beauty, Brilliance and Belonging in Our Homes, Classrooms, and Communities.” In We Be Lovin Black Children: Learning to Be Literate About the African Diaspora, eds. G.S. Boutte, J. King, G. Johnson, & L. King, 13–24. Gorham, ME: Myers Educational Press.

Kinard, T., J. Gainer, N. Valdez-Gainer, S. Long, & D. Volk. 2021. “Interrogating the ‘Gold Standard’: Play-Based Early Childhood Education and perpetuating White Supremacy.” Theory into Practice 60 (3): 322–32.

King, L.J. 2020. "Black History is Not American History: Toward a Framework of Black Historical Consciousness." Social Education 84 (6): 335–41.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 2017. "The (R)Evolution will not be Standardized: Teacher Education, Hip Hop Pedagogy, and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0." In Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World, eds. D. Paris & H.S. Alim, 141–56. New York: Teachers College Press.

Miller, E.T. 2015. "Race as the Benu: A Reborn Consciousness for Teachers of our Youngest Children." Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 30 (3): 28–34.

Muller, M. 2021. “Preparing Black Children to Identify and Confront Racism in Books, Media, and Other Texts: Critical Questions.” In We Be Lovin Black Children: Learning To Be Literate About The African Diaspora, eds. G.S. Boutte, J. King, G. Johnson, & L. King, 37–46. Gorham, ME: Myers Educational Press.

Morgan, H. 2020. "Misunderstood and Mistreated: Students of Color in Special Education." Voices of Reform: Educational Research to Inform and Reform 3 (2): 71–81.

NAEYC. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity

Pitts, J. 2020. “What Anti-Racism Really Means for Educators.” Learning for Justice. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/what-antiracism-really-means-for-educators

Roberts, S.O., & S.A. Gelman. 2016. "Can White Children Grow Up to be Black? Children’s Reasoning About the Stability of Emotion and Race." Developmental Psychology 52 (6): 887.

Sacks, V., & D. Murphey. 2018. “The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences, Nationally, by State, and by Race or Ethnicity.” Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. 2018. “The Archaeology of the Self.” Video. https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/media

Tatum, B.D. 1997. Why are all the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations About Race. London, UK: Hachette.

Touré. 2006. Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness? What It Means to Be Black Now. New York: Simon & Schuster.

US Department of Education Office of Civil Rights. 2016. 2013–2014 Civil Rights Data Collection: A First Look. Report. www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/2013-14-first-look.pdf

Wynter-Hoyte, K., S. Long, J. Frazier, J. Jackson. In press. “Liberatory Praxis in Preservice Teacher Education: Claiming Afrocentrism as Foundational in Critical Language and Literacy Teaching.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education.

Wynter-Hoyte, K., & M. Smith. 2020. “‘Hey, Black Child. Do You Know Who You Are?’ Using African Diaspora Literacy to Humanize Blackness in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Literacy Research 52 (4): 406–31.

Wynter-Hoyte, K., E.G. Braden, S. Rodríguez, & N. Thornton. 2019. "Disrupting the Status Quo: Exploring Culturally Relevant and Sustaining Pedagogies for Young Diverse Learners." Race Ethnicity and Education 22 (3): 428–47.

Wynter-Hoyte, K., M. Muller, N. Bryan, G. Boutte, & S. Long. 2019. “Dismantling Eurocractic Practices in Teacher Education: A Preservice Program Focused on Culturally Relevant, Humanizing, and Decolonizing Pedagogies.” In Handbook of Research on Field-Based Teacher Education, ed. D. Virtue, 50–60. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Meir Muller has earned rabbinical ordination as well as a doctorate in the area of early childhood education. Dr. Muller serves as an assistant professor in the College of Education at the University of South Carolina. [email protected]

Eliza G. Braden, PhD, is an associate professor of elementary education at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. Eliza has worked to affirm a pro-Black pedagogy in preparing preservice teachers for the classroom. [email protected]

Susi Long, PhD, is professor of instruction and teacher education at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, South Carolina, focusing on culturally relevant, humanizing, anti-racist, decolonizing practices in early childhood education. Her five books, numerous articles, course/program development, and professional development activities focus in these areas. Honoring this work, she was recently awarded the U of SC Martin Luther King Jr. Faculty Social Justice Award.

Gloria Swindler Boutte, PhD, is a Carolina Distinguished Professor at the University of South Carolina. Committed to equity methodologies and pedagogies, she is the coauthor of five books and nearly 100 articles.

Kamania Wynter-Hoyte, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of South Carolina. She teaches culturally relevant pedagogy, literacy methods, and linguistic pluralism courses. Her scholarship is anchored in African Diaspora literacies that foster liberation in teacher education and early childhood. [email protected]