Learning Stories: Observation, Reflection, and Narrative in Early Childhood Education

You are here

As an early childhood educator committed to equity of voice, I believe that educational activities with preschool children should be based on daily observations of children at play both in the classroom and outdoors. These observations should include teachers’ reflections and, as much as possible, families’ opinions and perspectives on their children’s learning, curiosity, talents, agency, hopes, and dreams. As a preschool teacher in a multi-language setting, I am required to conduct classroom observations to assess children’s learning. This has led me to the following questions:

- How can early childhood educators support and make visible children’s emergent cultural and linguistic identities?

- How can teachers embed story and narrative to document children’s growth and strengthen families’ participation in their children’s education?

In this article, I describe Learning Stories, a narrative-based formative assessment created by New Zealand early childhood education leaders. Learning Stories provide a way to document children’s strengths and improve instruction based on the interests, talents, and expertise of children and their families.

Learning Stories as Assessment

In New Zealand, educators use the Learning Stories approach to assess children’s progress. This narrative tool is a record of a child’s life in the classroom and school community based on teachers’ observations of the child at play and work. It tells a story written to the child that is meant to be shared with the family. Learning Stories serve as a meaningful tool to assess children’s strengths and help educators reflect on their roles in the complex processes of teaching and learning. As formative assessments, they offer the possibility of reimagining all children as competent, inquisitive learners and all educators as critical thinkers and creative writers, genuinely invested in their children’s work.

How Learning Stories Are Distinct

Learning Stories break away from the more traditional methods of teaching, learning, and assessment that often view children and families from a deficit perspective, highlighting what they cannot do. By contrast, Learning Stories offer an opportunity to reimagine children as curious, knowledgeable, playful learners and teachers as critical thinkers, creative writers, and advocates of play. Learning Stories are based on individual or family narratives, and they recognize the value of Indigenous knowledge. For native, Indigenous, and marginalized communities, the telling of stories or historical memoirs may be conceived as something deeply personal and even part of a “sacred whole,” as Maenette K.P. Benham writes. When we engage in writing and reading classroom stories—knowing how they are told, to whom, and why—we uncover who we are as communities and, perhaps, develop a deeper appreciation and understanding of other people’s stories.

Educators can use Learning Stories to identify developmental milestones with links to specific assessment measures; however, the purpose is not to test a hypothesis or to evaluate. At the root of any Learning Story is a genuine interest in understanding children’s lived experiences and the meaning teachers, families, and children themselves make of those experiences to augment their learning. As Laura Hope Southcott reminds us, “Teachers choose a significant classroom moment to enlarge in a Learning Story in order to explore children’s thinking more closely.”

Although no two Learning Stories will be alike, a few core principles underlie them all. The foundational components include the following:

- an observation with accompanying photographs or short videos

- an analysis of the observation

- a plan to extend a child’s learning

- the family’s perspective on their child’s learning experience

- links to specific evaluation tools

Suggested Format of a Learning Story

The following format is a helpful guide for observing, documenting, and understanding children’s learning processes at any given moment during the school day. It also may help teachers organize fleeting ideas into a coherent narrative to make sense of classroom observations or specific children’s experiences.

- Title: Any great story begins with a good title that captures the essence of the tale being told. Margie Carter suggests that the act of giving a title to a story be saved for the end, after the teacher has written, reflected on, and analyzed the significance of what has been observed, photographed, and/or video recorded.

- Observation: The teacher begins the story with their own interest in what the child has taken the initiative to do, describing what the child does and says. When teachers talk and write the story in the first person, they give a “voice” to the storyteller or narrator within. In their multiple roles as observers, documenters, and writers, teachers bring a personal perspective that is essential to the story. They write directly to the child, describing the scene in detail and narrating what they noticed, observed, or heard. Accompanying photographs, screenshots, or still frames of a video clip of the child in action serve as evidence of the child’s resourcefulness, skills, dispositions, and talents.

- What Does It Mean? (or What Learning Do I See Happening?): These are questions teachers can use to reflect, interpret, and write about the significance of what they observed. This meaning-making is best done in dialogue with other teachers. Multiple perspectives can certainly be included here; indeed, objectivity is more likely to be reached when the Learning Story includes a variety of voices or perspectives. Ask your coteachers or colleagues to collaborate to offer their pedagogical, professional, and personal opinions to the interpretation of the events.

- Opportunities and Possibilities (or How Can We Support You in Your Learning?): In this section, teachers describe what they can tentatively do in the immediate or distant future to scaffold and extend the child’s learning. How can they cocreate with children learning activities that stem from individual or collective interests? This section might also reveal teachers’ active processes in planning meaningful classroom activities while respecting children’s sense of agency.

- Questions to the Family: This is an invitation for a child’s family to offer their opinions on how they perceive their child as a competent learner. It is not uncommon for a child’s family to respond with messages addressed to the teacher. However, when teachers kindly request family members to reply directly to their child, they write beautiful messages to their children. Sometimes, the family might suggest ideas and activities to support their child’s learning both at home and school. They might even provide materials to enhance and extend the learning experience for all the children in the class.

- Observed Milestones or Learning Dispositions: Here, teachers can link the content of a child’s Learning Story to specific evaluative measures required by a program, school district, or state. They also can focus on the learning dispositions reflected in the story: a child’s curiosity, persistence, creativity, and empathy. The learning dispositions highlighted in a Learning Story reflect the emerging values of children and the values and beliefs of teachers, families, schools, and even the larger community.

Learning Stories in Practice

My preschool is part of the San Francisco Unified School District’s Early Education Department. Our school reflects the ethnic, economic, cultural, and linguistic mosaic of the school’s immediate neighborhood, which consists primarily of first- and second-generation immigrant families from Mexico, Central America, and Asia. When children enter our program, only about 10 percent feel comfortable speaking English. The others prefer to speak their home languages, meaning Spanish, Cantonese, and Mandarin are the most common languages in our school.

One child, Zahid, revealed his story-telling skills by sharing the story of his father’s attempt to cross the border between Mexico and the United States. (See “Waiting for Dad on This Side of the Border” and “Under the Same Sun” below.) The resulting Learning Stories provided a structure for documenting Zahid’s developmental progression over time and for collecting data on his language use, funds of knowledge, evolving creative talents, and curiosity for what takes place in his world—all of this in his attempt to make sense of events impacting his family and his community.

The Learning Stories framework honors multiple perspectives to create a more complete image of each learner. These include the voice of the teacher as narrator and documenter; the voice, actions, and behaviors of children as active participants in the learning process; and the voices of families who offer—either orally or in writing—their perspectives as the most important teachers in their children’s lives.

Waiting for Dad on This Side of the Border

May 2017

What happened? What’s the story?

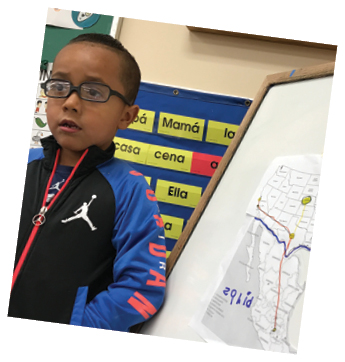

Zahid, I admire your initiative to tell us the tale of the travels your dad has undertaken to reunite with you and your family in California. On a map you showed us Mexico City where you say your dad started his journey to the North. You spoke about the border (la frontera), and you asked us to help you find Nebraska and Texas on our map because that’s where you say your dad was detained. We asked you, “What is the border?” and you answered: “It is a place where they arrest you because you are an immigrant. My dad was detained because he wanted to go to California to be with me.”

What is the significance of this story?

Zahid, through this story where you narrate the failed attempt of your dad to get reunited with you and your family, you reveal an understanding that goes well beyond your 5.4 years. In the beginning you referred to the map as a planet, but perhaps that’s how you understand your world: a planet with lines that divide cities, states, and countries. A particular area that called your attention was the line between Mexico and the United States, which you retraced in blue ink to highlight the place where you say your dad crossed the border. It is indeed admirable to see you standing self-assured in front of the class ready to explain to your classmates your feelings and ideas so eloquently.

What activities could we plan to support you in exploring this topic that you are so interested in?

Zahid, we could invite you to share with your classmates the tale of your dad’s travels and invite your friends to share the stories of their families too. We could take dictations of what it means for you to be waiting for Dad on this side of the border. We could support you to put into practice your interest in writing so that you could write a letter or message to your dad. Perhaps you would be interested in making a painting on a canvas representing your ideas and feelings with paint strokes and acrylic colors.

Zahid, we could invite you to share with your classmates the tale of your dad’s travels and invite your friends to share the stories of their families too. We could take dictations of what it means for you to be waiting for Dad on this side of the border. We could support you to put into practice your interest in writing so that you could write a letter or message to your dad. Perhaps you would be interested in making a painting on a canvas representing your ideas and feelings with paint strokes and acrylic colors.

What’s the family’s perspective?

Zahid is not very fond of writing, but he talks a lot and also understands quite a lot. He doesn’t like drawing but maybe with your support here at school he could find enjoyment in drawing or painting. —Mom

Under the Same Sun

May 2017

What happened? What’s the story?

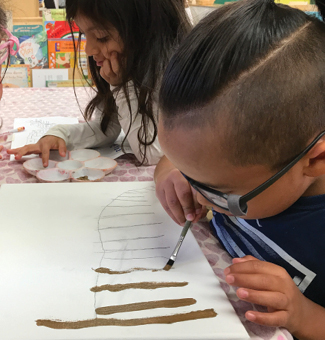

Zahid, of the several options we proposed to you to continue exploring the topic of the journey of your dad from Mexico to the United States, you chose a canvas, skinny paint brushes, and acrylic colors to represent the word frontera. Until now, you had hardly showed any interest in using painting tools, the process of writing, or making graphic representations of your ideas. Your preferred mode of expression was to communicate orally, and you have been doing it quite well! The fact you chose paintbrushes and acrylic paints reveals that every child should have the right to be an active participant when it comes to making decisions about their individual learning.

Zahid, of the several options we proposed to you to continue exploring the topic of the journey of your dad from Mexico to the United States, you chose a canvas, skinny paint brushes, and acrylic colors to represent the word frontera. Until now, you had hardly showed any interest in using painting tools, the process of writing, or making graphic representations of your ideas. Your preferred mode of expression was to communicate orally, and you have been doing it quite well! The fact you chose paintbrushes and acrylic paints reveals that every child should have the right to be an active participant when it comes to making decisions about their individual learning.

What is the significance of this story?

Zahid, I’m very pleased to see your determination to make a graphic representation of the word frontera. After so many sessions singing the initial sounds corresponding to each letter of the alphabet in Spanish, I thought you would be inclined to sound out the word frontera phoneme by phoneme and spell it out to write it on paper, but that was not the case. Instead, you decided to undertake something more complex, and you chose a paint brush and acrylic colors to represent (write) la frontera the way you perceive it based on the experiences you have lived with your family and, especially, with your dad.

What possibilities emerge?

Zahid, you could perhaps share with your classmates and your family your creative process. Throughout the entire process of sketching and painting you demonstrated remarkable patience since you had to wait at least 24 hours for the first layer of paint to dry before applying the next one. You chose the color brown to paint the wall that divides Mexico and the United States because that’s what you saw in the photos that popped out in the computer screen when we looked for images of the word frontera. You insisted on painting a yellow sun on this side of the wall because according to you, that’s what your dad would see on his arrival to California, along with colorful, very tall buildings with multiple windows. I hope one day you and your dad can play together under the same sun.

What’s the family’s perspective?

What’s the family’s perspective?

I think it is good for my son to have support from his teachers at school and that he can express what he feels or thinks. Although sometimes I wonder if it’s better to avoid the topic altogether. These months have been very difficult for everyone in the family but especially for him because he is the eldest. He says that he misses his dad even though he hasn’t seen him in a long time. And he says that he wants to go to Mexico when he’s older to be with Dad. —Mom

This article is an adaptation of “Learning Stories: Observation, Reflection, and Narrative in Early Childhood Education,” by Isauro M. Escamilla, published in the Summer 2021 issue of Young Children.

Also, check out the latest NAEYC book, Learning Stories and Teacher Inquiry Groups: Reimagining Teaching and Assessment in Early Childhood Education. You’ll learn more about how to integrate the Learning Stories approach and teacher inquiry groups into your setting.

Photographs: Header Image © Getty Images; Photos courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 4: Assessment of Child Progress

4A: Creating an Assessment Plan

4B: Using Appropriate Assessment Methods

4D: Adapting Curriculum, Individualizing Teaching, and Informing Program Development

Isauro M. Escamilla, EdD, is assistant professor in the Elementary Education Department of the Graduate College of Education at San Francisco State University. [email protected]