Our Proud Heritage. The Evolution of Family-Centered Services in Early Childhood Special Education

You are here

Those involved in the education of young children recognize the family as the primary institution in which young children are socialized, educated, and exposed to the foundations of their beliefs, values, and social and cultural identities. As such, families are young children’s first teachers as they learn about themselves and the world. Children’s enduring relationships with their families and their ongoing interactions within their routine environments are proximal processes that are “the primary engines of development” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris 2006, 797).

Because of the significant role families play in fostering young children’s development and learning, it is impossible to overemphasize the influence and importance of the interactions that young children experience within the context of their families. Family engagement in early childhood education is essential, as are strong, reciprocal relationships and collaboration among early childhood educators and families. Therefore, all involved in the education and care of young children should be invested in understanding and building on the progress that has been made in family-centered services.

During the early childhood years, many delays and disabilities are identified in young children. Early identification and intervention are key: they can be more effective than waiting until later in childhood and beyond. Everyone who interacts with the child during those early years will likely play a role in identification, creating plans, and/or implementing services. This includes early childhood educators who may vary greatly in training and experiences in early childhood special education. Therefore, all who are involved would benefit from having a foundational understanding of the history of family involvement in early intervention/early childhood special education (EI/ECSE) and its connection to current theories, policies, and practices.

This article highlights the evolution of family-centered services in EI/ECSE through which young children with delays and disabilities, birth through age 8, receive services. Multiple factors in the history of family services that have influenced the current emphasis on family-centered practices are recognized, including

- the changes in family characteristics in the United States

- the family movement to advocate for increased and improved services

- philosophical changes related to family engagement, teaming, and inclusion

- evidence-based practices for designing instruction and intervention that reflect a family-centered approach

- EI/ECSE and other professional standards that focus on family-centered practice

The expectation is that the increased focus on a family-centered approach will lead to improved services for all young children and families. When families are valued by professionals and collaborative relationships are developed among families and educators, children ultimately benefit. The need for strong collaboration among educators and families, as well as professionals representing multiple disciplines, is often intensified when considering young children with delays or disabilities. Additionally, families of young children with delays or disabilities have remained an instrumental force in ensuring quality services and moving the field of EI/ECSE forward.

Changes in Family Characteristics in the United States

The dramatic changes in the characteristics of families in the United States over the last several decades have influenced the evolution of family-centered services. For example, in the United States today there are many family configurations, including—but not limited to—adolescent (teen) parents, single-parent households, families with adopted children, families with foster children, grandparents or other relatives raising children, two parents of the same gender, blended families, and other constellations. Families also reflect the increased cultural diversity recognized in the US, which has implications for the values and beliefs that directly and indirectly shape how a child perceives, interacts, develops, and learns within their family and community (Turnbull et al. 2022).

Also represented in US society today is an increased number of hybrid families. Hybrid families are those that have redefined themselves and produced something new and different from their families of origin (Aldridge, Kilgo, & Bruton 2016). For example, in a hybrid family each parent may have a different ethnic and religious background. Rather than exclusively adopting the cultural and religious practices of one parent or the other, this type of family observes a blend of both cultures and religious practices that differs in many respects from either parent’s family of origin.

These changes in family configurations and social and cultural values, beliefs, and identities in current US society have added to the complexity of family-professional relationships (Hanson & Espinosa 2016). In the past, educators focused on teaching children what they thought they should learn without considering the desires and preferences of families or the influence of cultural and social contexts of families. As family characteristics have changed, all early childhood educators, including those involved with special education, have needed—and been called—to discover the most effective, responsive methods to provide individualized support and services within the social and cultural contexts of each child and family (Aldridge, Kilgo, & Bruton 2016). This has led to family-centered practices currently in place.

The Family Movement in EI/ECSE

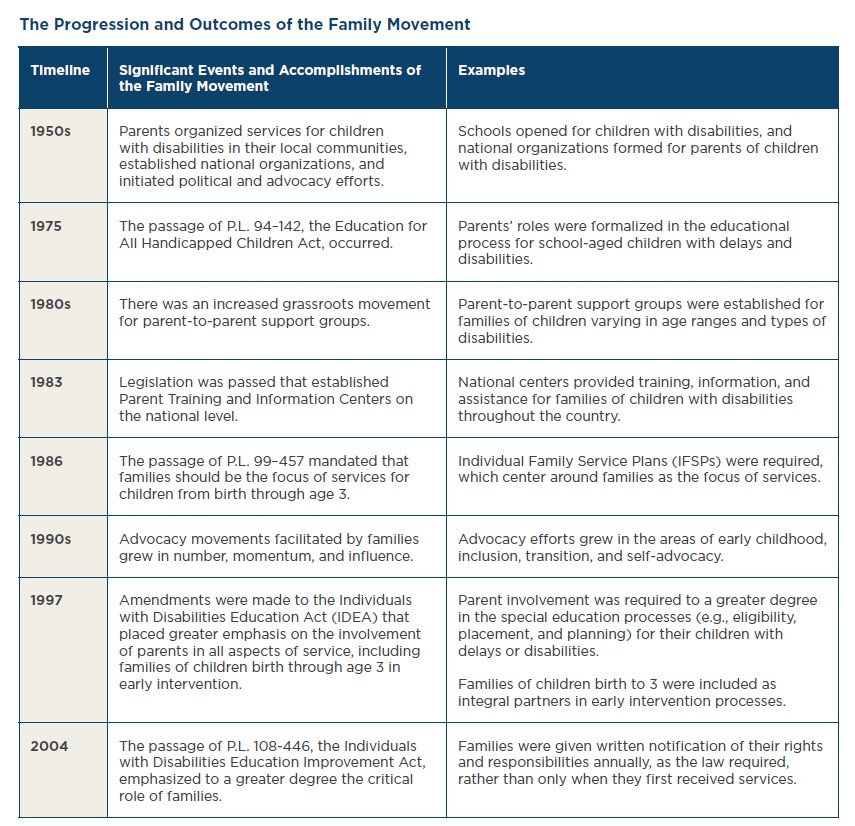

Family involvement and engagement in programs for children with disabilities is not a new concept. In fact, the history of family involvement in the education of young children with disabilities has occurred over many years, gaining increased attention in the 1960s in the United States. Many factors contributed to this emphasis in the 1960s and 1970s; among them were political, social, economic, and educational issues and events. Political movements—such as the civil rights and women’s rights movements, policy and advocacy work, and legislative actions—led to the current emphasis placed on the provision of high-quality programs for young children with delays and disabilities and their families provided by well-prepared professionals and grounded in evidence-based practices. A chronology of the family movement is represented in “The Progression and Outcomes of the Family Movement” below. This highlights the strong influence of parents in advocating for and shaping legislation and family-centered services in EI/ECSE.

Many family members have participated in professional and parent organizations, as well as in the provision of parent-to-parent supports. Parent-to-parent programs provide informational and emotional support to families of children with disabilities. Most often, this is done by matching one family who is new to the process or services with an experienced family who has a child with a similar disability. In these ways, families will continue to have a strong voice in advocating for legislation and services for their children with delays and disabilities (Turnbull et al. 2022).

Philosophical Changes

Key philosophical changes have also influenced the evolution of family-centered practices. In the mid-1980s, Ann Turnbull and Jean Ann Summers called for a major change in thinking in the disability field that was likened to a “Copernican Revolution”; that is, a change in common understanding of a specific topic (similar to when Copernicus revolutionized scientific thought by suggesting the sun was the center of the universe, not Earth). Turnbull and Summers stressed that the traditional view of early childhood services should no longer be the center of the special education “universe.” Instead, the child and family must be in the center of the universe, and special education services should be one of the many “planets” encircling each child and family to meet their individualized needs. This paradigm shift led to a new set of premises, practices, and options for services (Turnbull & Summers 1985, as cited in Edelman, Greenland, & Mills 1992), such as a family selecting the type of program or school setting for their child or what goals or outcomes to prioritize. A family-centered perspective today permeates all aspects of early childhood services, including assessment, program planning, instruction and intervention activities, transitions, and program evaluation (Gargiulo & Kilgo 2020).

The specific requirement of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) to enhance the capacity of families to meet the needs of their children also influenced the philosophical changes associated with a family-centered approach. This requirement explicitly acknowledged the family as the central focus of EI/ECSE services and the primary decision makers in the special education process (Trivette & Banerjee 2015; Dunst & Espe-Sherwindt 2016; Keilty 2016). The emphasis on the family, along with other philosophical and legislative changes, had major consequences for EI/ECSE programs and services (Johnson, Rahn, & Bricker 2015).

The Changing Role of Educators in Working with Families

These philosophical changes, among other factors, have strengthened the evolution to family-centered practices. Dunst and colleagues (1991) and Gargiulo and Kilgo (2020) traced the history of the role of educators in working with families of young children with delays and disabilities.

- The first approach Dunst and colleagues described was a professional-centered activity model where the professional was the sole source and dispenser of knowledge and expertise. They note that families were considered dysfunctional and incapable of addressing and resolving their own problems.

- The family-allied approach came next, where families were viewed as teachers of their children who should implement family interventions prescribed by the professionals.

- Gradually, the family-allied approach was replaced with a family-focused model. Families were viewed as competent and capable of collaborating with professionals; however, most educators believed that families needed their knowledge and assistance to be successful. Practitioners viewed families more positively than in the past, but unfortunately, they often misunderstood family practices and neglected the complexities of families’ lived experiences. They also did not give sufficient attention to the role of family-centered practices in “supporting and strengthening meaningful changes in child, parent, and family functioning” (Dunst & Espe-Sherwindt 2016, 38).

- The prevailing model today, the family-centered model, views the family as the center of the service delivery system. As such, services are planned around families with individualized support and resources and offered as desired (Trivette & Dunst 2005). This approach is consumer-driven, which means that families are not mere recipients of services but are active partners in planning and implementing service delivery processes (Gargiulo & Kilgo 2020).

To arrive at this prevailing model, influences have come from the fields of general early childhood education, special education, compensatory education (e.g., Head Start), and related service fields, as well as professional organizations. The Division for Early Childhood (DEC), NAEYC, and other professional organizations have developed evidence-based recommendations, standards, and policies concerning families. These documents emphasize that the benefits of family-professional collaboration early in children’s lives extend far beyond the early years.

Evidence-Based Practices

Research findings over time have provided evidence that family-centered practices have positive outcomes for young children with delays and disabilities and their families (Bruder 2010; DEC 2014). A variety of studies and syntheses of the research literature have contributed to current thinking and practices, highlighting the mutual benefits of such collaboration among families and educators who work together to reach shared outcomes and goals (Blue-Banning et al. 2004; DEC 2014; Trivette & Banerjee 2015; Dunst & Espe-Sherwindt 2016).

The DEC Recommended Practices (2014) were developed to help bridge the gap between research and practice by providing a guide for the practices that have been found to have better outcomes in EI/ECSE. They are grounded in evidence-based practices that reflect current research as well as professional and family wisdom and values. They clarify the parameters of family-centered practices, which provide the foundation for high-quality services for young children with disabilities and their families. The DEC Recommended Practices (2014) describe the three themes of a family-centered approach in EI/ECSE:

These evidence-based practices regarding family-centered services in the DEC Recommended Practices (2014) have empowered EI/ECSE professionals to deliver the most effective interventions available to improve services provided to young children and families.

EI/ECSE Professional Standards

In addition to evidence-based practices, the field of EI/ECSE has new Initial Practice-Based Professional Preparation Standards for Early Interventionists/Early Childhood Special Educators (Berlinghoff & McLaughlin 2022). The EI/ECSE standards are the culmination of many years of work in defining what early childhood special educators are expected to know and be able to do upon entry into the profession. These efforts involved many individuals and required tremendous commitment to the research, practice, policy, advocacy, and professional development that underlie these standards. These EI/ECSE standards represent the first stand-alone standards to focus specifically on the preparation of EI/ECSE professionals who work with young children with delays and disabilities, birth through age 8. They emphasize the distinctive skills and knowledge required for specialization in working with young children with delays or disabilities and their families.

The EI/ECSE standards emphasize the importance of family-centered practices (Berlinghoff & McLaughlin 2022). They include the knowledge and skills needed by EI/ECSE personnel to work in partnership with families and to effectively engage in teaming and collaboration. Family-centered practices are threaded throughout the standards, echoing the following elements (DEC 2020):

- an emphasis on families, especially as decision makers and partners in supporting children’s development and learning and strengthening family capacity

- recognition and respect for diversity as represented by the cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic conditions of families, staff, and programs

- an expectation for equity for all children and families

- an expectation for individualized, developmentally appropriate intervention and instruction based on sound knowledge of each child’s and family’s assets, needs, and preferences for services

- an emphasis on partnership, collaboration, and team interaction that influences the availability and quality of services for children and families, as well as team structures and processes for collaboration

Conclusion

The history of understanding, recognizing, and involving families in EI/ECSE has changed and improved over time. This evolution is connected to ongoing changes in legislation, policies, evidence-based practices, and standards for professionals. This has led to the family-centered practices, policies, and expectations for practitioners of today. The history and emergence of family-centered policies and practices are important for all those involved in early education to understand. Families will continue to play a major role in moving the field of early childhood forward as they engage in collaborative relationships with educators and advocate for appropriate policies, services, and practices for their children.

Therefore, moving forward, educators must realize the importance of considering each and every child within the context of their families, of valuing family-centered services, and of implementing practices to support families. Partnering with families of young children, both with and without disabilities, will create equitable early learning opportunities across multiple contexts (school, home, and community settings). As these policies and practices continue to evolve, everyone participating in the education and care of young children should be invested in furthering this progress and in ensuring the most effective services for every child.

Learn More About a Family-Centered Approach to EI/ECSE

-

Division for Early Childhood (DEC) Recommended Practices

This is a set of practices developed by DEC based on the most current research as well as the wisdom and experiences of those in the field. These practices guide professionals and families on the most effective ways to promote development and learning for young children with delays or disabilities. -

Early Childhood Technical Assistance (ECTA) Center

This center provides an array of resources to assist early intervention and early childhood special education programs in developing high-quality services, implementing evidence-based practices, and improving outcomes for young children with delays or disabilities and their families. -

IRIS Center

This module addresses the importance of engaging families of children with disabilities in the educational process. Highlighted are some key factors that affect families along with suggestions for creating and developing relationships among families and professionals. -

PACER Center

This is a national information center for families of individuals with all disabilities, from birth to young adults. It offers publications, training, and other resources related to education and other services that families may need in making decisions about and for their children with disabilities.

Photograph: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Aldridge, J., J. Kilgo, & A. Bruton. 2016. “Beyond the Brady Bunch: Hybrid Families and Their Evolving Relationships with Early Childhood Education.” Childhood Education 92 (2): 140–148.

Berlinghoff, D., & V. McLaughlin, eds. 2022. Practice-Based Standards for the Preparation of Special Educators. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Blue-Banning, M., J. Summers, H. Frankland, L. Nelson, & G. Beegle. 2004. “Dimensions of Family and Professional Partnerships: Constructive Guidelines for Collaboration.” Exceptional Children 70 (2): 167–184.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & P. Morris. 2006. “The Bioecological Model of Human Development.” In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Models of Human Development, 6th ed., eds. W. Damon, & R.M. Lerner, 793–828. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Bruder, M. 2010. “Early Childhood Intervention: A Promise to Children and Families for Their Future.” Exceptional Children 76 (3): 339–355.

DEC (Division for Early Childhood). 2014. DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education 2014. Report. https://www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices

DEC (Division for Early Childhood). 2020. Initial Practice-Based Standards for Early Interventionists/Early Childhood Special Educators. Report. https://www.dec-sped.org/ei-ecse-standards

Dunst, C., & M. Espe-Sherwindt. 2016. “Family-Centered Practices in Early Childhood Intervention.” In Handbook of Early Childhood Special Education, eds. B. Reichow, B. Boyd, E. Barton, & S. Odom, 37–56. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Dunst, C., C. Johanson, C. Trivette, & D. Hamby. 1991. “Family-Oriented Early Intervention Policies and Practices: Family-Centered or Not?” Exceptional Children 58 (2): 115–126.

Edelman, L., B. Greenland, & B.L. Mills. 1992. Building Parent/Professional Collaboration: Facilitator’s Guide. Baltimore, MD: Kennedy Kreiger Institute.

Gargiulo, R.M., & J.L. Kilgo. 2020. An Introduction to Young Children with Special Needs: Birth through Age Eight, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hanson, M., & L. Espinosa. 2016. “Culture, Ethnicity, and Linguistic Diversity: Implications for Early Childhood Special Education.” In Handbook of Early Childhood Special Education, eds. B. Reichow, B. Boyd, E. Barton, & S. Odom, 455–472. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Johnson, J., N.L. Rahn, & D. Bricker. 2015. An Activity-Based Approach to Early Intervention, 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Keilty, B. 2016. The Early Intervention Guidebook for Families and Professionals: Partnering for Success, 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Trivette, C., & R. Banerjee. 2015. “Using the Recommended Practices to Build Parent Competence and Confidence.” In DEC Recommended Practices: Enhancing Services for Young Children with Disabilities and Their Families (DEC Recommended Practices Monograph Series No. 1), 66–75. Washington, DC: Division for Early Childhood.

Trivette, C., & C. Dunst. 2005. “DEC Recommended Practices: Family-Based Practices.” In DEC Recommended Practices: A Comprehensive Guide to Practical Application in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education, eds. S. Sandall, M. Hemmeter, B. Smith, & M. McLean, 107–120. Washington, DC: Division for Early Childhood.

Turnbull, A.P., R.H. Turnbull, G.L. Francis, M. Burke, K. Kyzar, S.J. Haines, T. Gershwin, K.G. Shepherd, N. Holdren, & G.H.S. Singer. 2022. Families and Professionals: Trusting Partnerships in General and Special Education, 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson.

Dr. Jennifer L. Kilgo is professor and coordinator of the Graduate Program in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Jennifer is the principal investigator of the Project TransTeam grants that provide interdisciplinary education. She works on the national level with the Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children. [email protected]