Assessing Agency in Learning Contexts: A First, Critical Step to Assessing Children

You are here

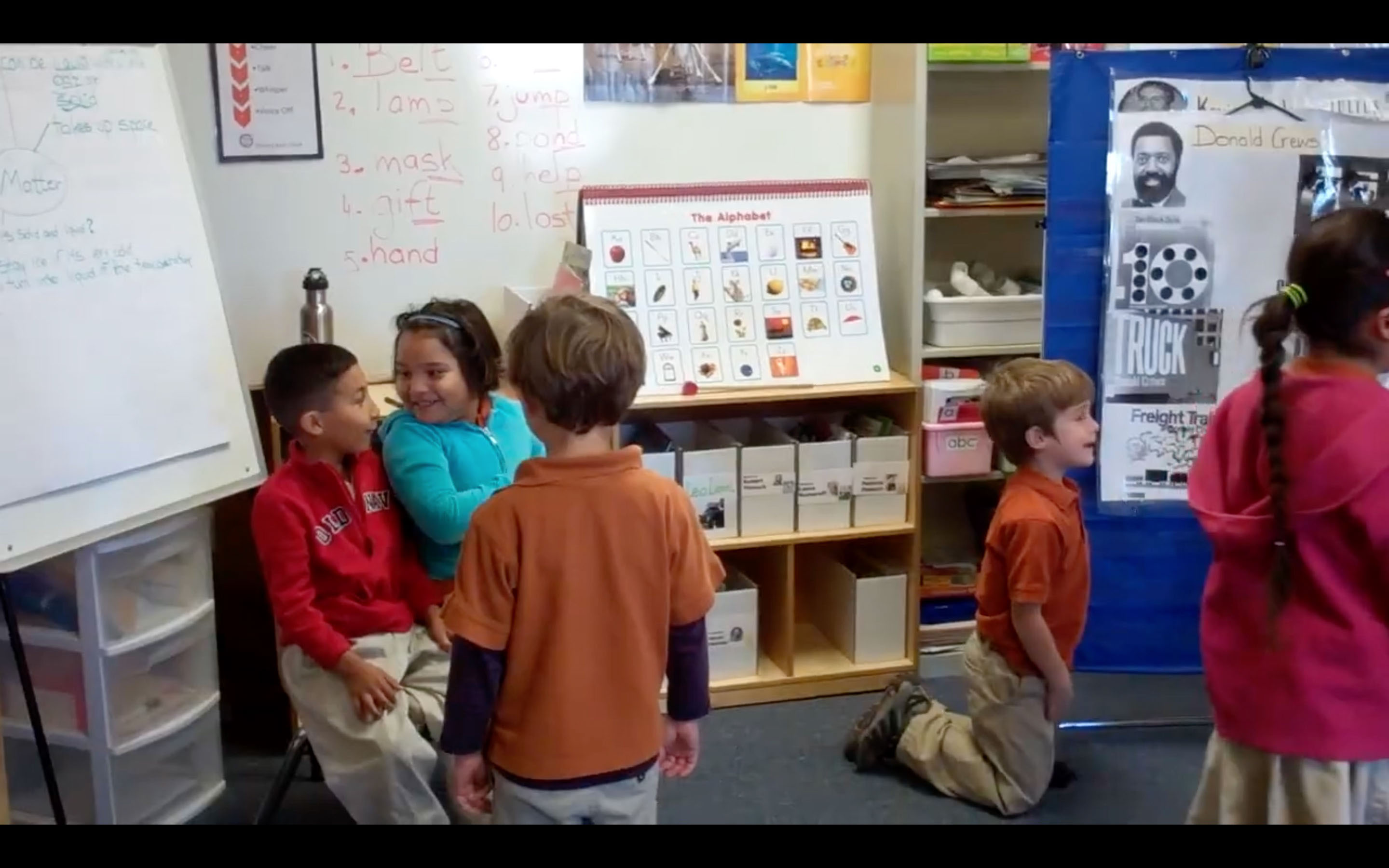

It’s center time, or “work time” as they call it in Ms. Amaya’s and Ms. Jackson’s pre-K inclusion classroom. A group of children are engaged with various materials and activities on one of the classroom rugs: Omar is putting together an airplane puzzle. Beto is building an aircraft with bristle blocks. Michael is alternating between reading a book aloud and playing. Ms. Jackson is sitting on the rug, holding up The Duckling Gets a Cookie!? by Mo Willems for Michael to read.

Michael: (loudly and dramatically, reading the mischievous pigeon’s line) Nooooooooooo!

Ms. Jackson: That’s a long no, right Michael?

(Beto pauses his play to look at the book and listens as Michael continues his animated reading.)

Michael: (reading in mock frustration) It is not fair!

(Omar turns around to look at Michael, then looks at the book and laughs. Ms. Jackson laughs too as she turns the page. Beto smiles. As he continues to build, he starts adding dialogue to his play with the aircraft.)

Beto: “Hello? Knock, knock!”

Michael: (propped on his knees and reading as his body sways) Pigeons like cookies too! WHY DID YOU GET THAT COOKIE?

(Michael’s faked exasperation is met with more laughter.)

In this pre-K inclusion classroom in the southern United States, teachers are intentional about setting up the learning context—or the space, schedule, and expectations—to encourage children to initiate and influence engagements in their environment. Teachers “create and foster a community of learners” (NAEYC 2020, 15) in which children can build on skills, abilities, or competence by following their interests and ideas. During work time, children use their agency to interact with materials and each other in open-ended, child-directed ways. This allows teachers to observe and document their capabilities and skills authentically.

For Michael, a 4-year-old Black boy with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), this context fostered his joyful learning and created opportunities for him to achieve his full potential (NAEYC 2020, 5). Michael enacted his agency to read, express, and share something that he enjoys. He got to choose a book and take the lead in reading it from a spot that was physically comfortable and where he could move his body. His experience reading to his teacher and classmates both demonstrated and expanded a range of academic and social and emotional knowledge, skills, and talents. This allowed Ms. Jackson to encourage Michael with verbal and nonverbal feedback and to observe that

- he is an avid reader with a reading level and abilities that exceed grade-level expectations.

- he is expanding his ability to lift words from the page in a way that is engaging and exciting for him and his community.

- he explores the range of his voice, refines his reading abilities, and shares what he reads with peers who are playing around him.

- he experiences the joy of contributing to his classmates’ laughter and enjoyment.

In Michael’s classroom, he was able to exercise his agency regularly, with the knowledge that it would be welcomed instead of disciplined (Park et al. 2021). Yet in rigid, overly structured early learning environments that prioritize compliance and control, young children cannot show what they know and can do (Adair & Colegrove 2021). This is particularly true in state-funded programs that serve communities of color that are economically challenged (Early et al. 2010). In this article, we explain the need to assess learning environments to determine whether young children have the agency to demonstrate their full range of abilities, interests, and knowledge. We then lay out how educators can use these environments in their assessment practices. The examples described and documented are drawn from two multisite, large-scale studies: Agency and Young Children (Adair 2014; Adair & Colegrove 2021) and Civic Action and Young Children (McManus et al. 2019; Payne et al. 2020). These studies focus on the range of capabilities and communal and civic engagements young children of color demonstrate when they are provided ample amounts of agency in their daily schooling contexts.

Agency and Young Children

The Agency and Young Children Study was funded by the Foundation for Child Development and recently published as a book titled Segregation by Experience: Agency, Racism and Learning in the Early Grades. In this study, researchers spent one academic year in a first-grade classroom where children of Latino/a/x immigrants and African American children had an atypical amount of agency—or choices, freedom, time, and space to follow their interests and ideas. Children demonstrated a significant range of capability expansion that is hard or impossible to see in controlling, strict classrooms.

Now, in a study funded by the Brady Education Foundation, researchers are testing a culturally flexible tool that will support agency in classrooms so that more children—particularly children of color—will be offered dynamic and sophisticated learning experiences that support their agency and capability expansion. You can learn more about this work at http://sites.edb.utexas.edu/agency-and-young-children/.

Agency Supports Sophisticated Learning and Community Building

We (the authors) share identities and experiences as early childhood researchers, teacher educators, former early childhood teachers, and mothers. We also share the belief that children are smart, capable, and caring. They deserve to receive dynamic, sophisticated, community-rooted, and culturally sustaining learning experiences in their everyday schooling. We approach learning as an active endeavor in which teachers support young children’s agency to move, observe, initiate, and engage to see themselves as capable and competent.

Our backgrounds bring a range of perspectives. Natacha Ndabahagamye Jones (first author) is a Black immigrant woman, a doctoral candidate, and a past research participant in the Agency and Young Children Study led by Jennifer Keys Adair (third author). Amber T. Fowler (second author) is a Black woman born in the US and a doctoral student. She experienced her childhood as a foster child in the southern United States. Jennifer Keys Adair is a White woman born in the United States, a professor, and a researcher who has studied agency with BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people of color) communities for 15 years.

Assessing young children authentically requires educators to understand the various and complex ways children make meaning through the reciprocal relationships they have with adults, their learning environments, and multiple communities (Darling-Hammond & Snyder 2000; Carr & Lee 2012; NAEYC 2020). We take the position that teachers, administrators, and other educational stakeholders must assess, or evaluate, these learning contexts before requiring young children to be directly assessed. Doing so ensures that

- children are provided multiple and consistent opportunities to use their agency.

- children are able to show the full range of their capabilities.

- educators select and use strengths-based assessments that recognize and support children’s capabilities and the holistic ways they learn, including through play.

Along with our colleagues in the Agency and Young Children Research Collective, we have studied how agency impacts the learning and development of young children from African American and Latino/a/x immigrant and nonimmigrant communities (Adair 2014; Adair & Colegrove 2021). Our research and practice have shown that when young children have multiple and consistent opportunities to use their agency, they develop, demonstrate, and refine sophisticated knowledge-making skills that are essential to their learning and growth. These skills and ways of knowing include observation, inquiry, open-ended discussion, critical and creative thinking, problem solving, and initiative (Gopnik 2012; Helm & Katz 2016; Souto-Manning et al. 2019; NAEYC 2020). They are critical to child development and equitable learning.

Consistent access to agentic learning contexts fosters children’s ability to expand on their curiosity and their cultural, linguistic, and embodied experiences. It also enhances their knowledge, skills, and sustained learning engagements. Agency facilitates young children’s cocreation of caring and dynamic communities of learners, which provides many opportunities to show care; advocate for one another; negotiate and regulate their play, interactions, and access to resources; and balance individual needs with those of the community (Payne, Falkner, & Adair 2020). With agency, children demonstrate ownership of their learning and responsibility for each other’s well-being and for an environment that reflects and honors multiple ways of being and learning.

Assessment Practices and Inequitable Access to Agentic Learning

While many educators and families would agree that agentic practices are desirable for young children, accountability pressures that prioritize academic skills, formal testing, individualized learning, and fewer opportunities for holistic and playful learning have become standard—even in early childhood education (Bassok, Latham, & Rorem 2016). Early childhood teachers are often expected to assess children in ways that are not developmentally, culturally, or linguistically responsive (Paris 2012; Blessing 2019). This significantly limits the attention they can give to creating caring, agentic, equitable learning contexts where children can fully demonstrate their knowledge and skills (Adair & Sachdeva 2021; Muller et al. 2022).

Many schooling contexts for young children of color prioritize controlling, measuring, and intervening rather than providing learning environments with multiple ways and opportunities for children to show what they know and can do (Cervantes-Soon, Degollado, & Nuñez 2020; Wright 2021). Denying young children their agency in school means they do not have much time to collaborate, problem solve, work through conflict, or experience other kinds of community- or civic-building activities. Most importantly, severely limiting agency also limits how many capabilities children can demonstrate. Imagine that Michael, from the opening vignette, was only allowed to read independently, sit still during specific times, engage with books chosen by his teacher, and be formally assessed out of context. He might not show the same skills and enthusiasm. His teachers would not be able to see the breadth of his skills, and he might not be able to expand on them.

To further illustrate, consider another instance from Ms. Amaya’s and Ms. Jackson’s pre-K inclusion classroom.

One day at recess, Ms. Smith, a “floater teacher” who prioritizes control and compliance over agency and learning, is supervising the children’s play. Michael is playing on a concrete accessibility ramp with a truck he brought over from the sand area. Ms. Smith tells him to keep the truck by the sand. Michael follows her instructions, but a minute later, he carries the truck to the ramp again. Ms. Smith scolds him and tells him to take the truck back. When he doesn’t, she walks over and pulls Michael by the hand to the sand area. Moments later, Michael tries to move the truck again. Ms. Smith scolds him again.

Ms. Amaya (the lead teacher) comes back from break and notices what Michael is doing. Ms. Smith leaves. Michael takes the truck back to the top of the ramp and pushes it down. He squeals with excitement and runs to get it. He goes back to the top, then pushes it again.

Meanwhile, a group of girls are chasing each other on the ramp. One of them, Nicole, notices when the truck hits her feet and stops. Her feet have become a barrier. She moves her feet and opens them wide so that the truck can pass through. Michael runs to the bottom of the ramp, retrieves the truck, and runs back to the top. Nicole prepares for the truck to go through her legs again. She stands with her feet wide, trying to align them perfectly with Michael’s truck. Michael pushes the truck, and it goes through Nicole’s legs. Nicole starts moving all over the ramp so that Michael has to move and aim the truck to go through her legs. This experiment continues until Nicole runs off to the sand area. Ms. Amaya watches as Michael continues to push the truck down the ramp with children moving in and out of the scene.

During these interactions, Ms. Amaya observed that Michael demonstrated inquisitive and cognitive skills as he gained an emerging understanding of force, motion, gravity, friction, and velocity. However, she was most impressed by Michael’s capabilities to include others in his play and to adapt what he was doing to the interests of those around him. Because he has ASD, Michael often played in isolated ways and struggled to include others. Pushing the truck down the ramp with Nicole demonstrated a range of expanded capabilities across many domains. Most importantly, Michael included others and contributed to a group endeavor.

If Ms. Smith had remained in charge, Michael’s capabilities would not have been observed. This is not because he did not have them; rather, the learning context under Ms. Smith’s direction did not allow Michael to show his full range of knowledge and interests. Likewise, if Ms. Smith had been the floater teacher when Michael started reading The Duckling Gets a Cookie!?, Michael might not have experienced the joy and contribution he did with Ms. Jackson. He might not have been able to demonstrate all of his skills, nor would his teachers have been able to observe them.

Assessing Contexts: Pushing Back Against Bias

Children are assessed in contexts assumed to be neutral; however, even well-intentioned adults may hold biases and assumptions about children’s families, communities, and social identities (such as race, culture, languages, and abilities). Young children’s “social identities bring with them socially constructed meanings that reflect biases targeted to marginalized groups, resulting in differential experiences of privilege and injustice” (NAEYC 2019, 14). In addition, the tools and methods used to assess young children can reinforce deficit views about children of color and their communities. This can occur even when the practices and materials used appear to be developmentally appropriate and/or culturally sustaining.

These deficit views are compounded by historical and ongoing individual and structural racism. Narratives of an “achievement gap” position children of color as deficient compared with White children and as problems to be “fixed” instead of a more accurate view: seeing the gap as an educational manifestation of social inequalities that are worsened by narrow, one-size-fits-all learning experiences (Boykin & Noguera 2011). Redressing these inequities refocuses our understanding of young children’s knowledge making and curriculum as rooted in relationships and engaged participation. “Assessing a Learning Context for Agency” above offers some guidance on ensuring that learning contexts are caring, agentic, and equitable.

Assessing a Learning Context for Agency

Here are some questions we can ask ourselves as educators to assess whether our learning context supports children’s agentic practices.

Do I/we

▢ provide a range of opportunities for children to generate and share ideas?

▢ listen to and follow up on children’s ideas?

▢ provide a range of opportunities for children to influence lessons, investigations, play, and other activities?

▢ offer multiple opportunities for children to work with each other?

▢ provide multiple ways for children to contribute to and shape the classroom community?

▢ observe and listen to children before intervening?

▢ offer a range of opportunities to use space flexibly and move around often and in different ways?

▢ support children using a variety of materials (natural or manmade) in a variety of ways?

▢ give children time to explore what they are interested in within their environment (indoors and outdoors)?

▢ encourage and welcome children’s initiatives on how they advocate and care for one another and for their environment?

If we answer yes to any of these questions, we can also reflect on whether we make these experiences accessible to all children equitably or whether we make children earn or prove they are worthy of such experiences.

Agency Is a Requirement for Demonstrating Social and Collective Capabilities

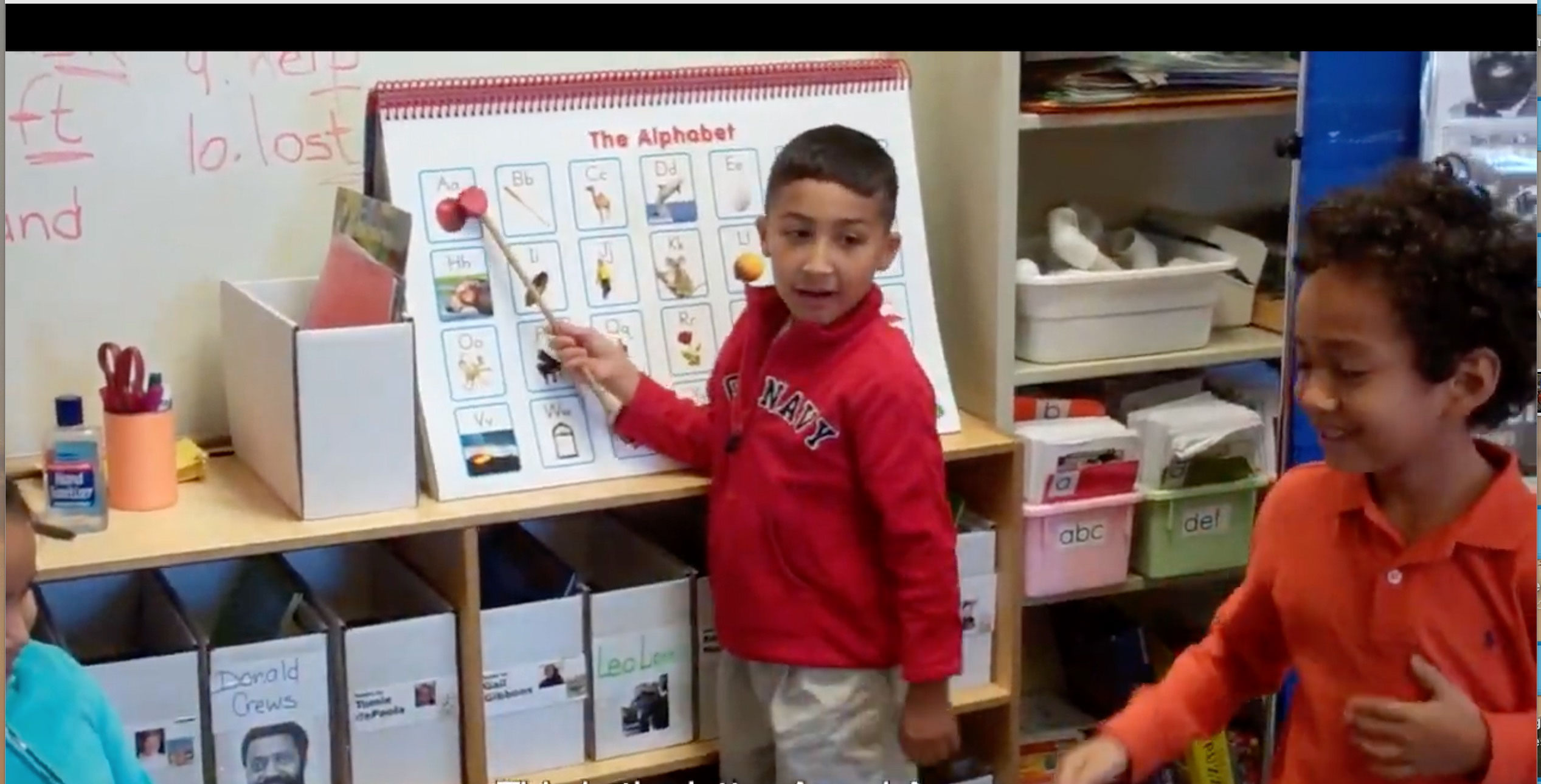

It is transition time in Ms. Bailey’s first-grade classroom. While she sets up for science, a group of children gather near the corner of the room where the class meets for mini lessons, read alouds, and other whole-group activities. Celeste and Robert are both sitting in their teacher’s chair with the numbered craft sticks that Ms. Bailey uses for various activities. They are singing “Hickety Pickety Bumblebee” and disagree over the song’s lyrics.

Celeste: It’s hickety!

Robert: I said pickety! (He continues singing “Pickety pickety bumblebee.”)

Celeste: (smiling and modeling the proper lyrics patiently) Look. Hickety, pickety bumblebee.

(They continue singing. Robert eventually gets up from the chair, and Celeste takes over the chant. She gains the attention of a few more classmates.)

Celeste: Hickety, pickety bumblebee . . .

Diana: Who can sing their name for me?

Ms. Bailey pauses in her work and begins to watch the children. As she observes, Celeste shuffles through the craft sticks in search of Diana’s number. Like most of the children, she has memorized her classmates’ numbers and easily finds Diana’s. Diana now sits in the teacher’s chair with the craft sticks. She repeats the chant and calls on Kata, who is across the room. Kata comes immediately to sit in the teacher’s chair.

Robert has moved over to face the alphabet chart and is using an apple-ended pointer to point to the letters. “This is A,” he says, “and A says /a/. This is B, and B says /b/.” Before Robert can get to letter C, Peter tries to pull the pointer from him but is unsuccessful. Peter holds his chest and smiles in defeat, then goes behind the easel to get a different pointer. Robert resumes the phoneme sounds.

Children learn best when they find relevance and connections to the learning and their environment (Souto-Manning 2014). Even in unplanned and transitional activities, children benefit when they have ample amounts of agency. They can “experience responsive interactions that nurture their full range of social, emotional, cognitive, physical, and linguistic abilities” (NAEYC 2019, 5), expand their multidimensional capabilities, and support the cocreation of a caring community of learners.

As seen in the vignette, the students in Ms. Bailey’s class were able to move, explore, and be playful, even during transitions. The classroom tools they had access to also facilitated their learning and connections. As they engaged with one another and their environment, Ms. Bailey observed and documented a range of mathematical and early literacy skills and knowledge—some emerging, and some reaching mastery. For instance,

- Celeste and Robert demonstrated phonological awareness skills with the rhyming song.

- Robert demonstrated one-to-one correspondence, the ability to read left to right and sweep to the next line, letter recognition, and phonemic awareness as he tapped and said the name and sounds of each of the letters on the alphabet chart.

- Celeste could identify one- and two-digit numbers and match those numbers to the corresponding classmate’s name.

Ms. Bailey was also able to observe and document communal, interpersonal, and social and emotional skills and engagements:

- Celeste and Robert were able to initiate an activity and share materials, including the teacher’s chair.

- Celeste listened to her peer’s chant and patiently corrected his error.

- Celeste knew which craft stick was Diana’s. She sought it in the cup with an intent to call on her friend within the rules of the game they had established.

- Diana demonstrated an ability to expand a child-led activity to her class community when she chose Kata’s craft stick.

- Kata’s eagerness to join the game demonstrated she felt enjoyment and belonging as a community member.

- Robert and Peter figured out child-centered resolutions to seeking the same pointer. While some might conclude that the boys lacked self-regulation because they were fighting over the pointer, we see the opposite: the boys figured out a solution with no adult direction in order to return to the alphabet chart or move on to other activities.

Documenting Agency

Anecdotal observations and authentic assessments are useful ways to document children’s individual and communal capabilities, such as the ones described above. (See “Being a Keen Observer of Young Children” below.) In addition to the formal assessments and benchmarks required by the state, Ms. Bailey included her observations about children’s capabilities in the portfolios she kept for each child.

When young children have opportunities to use their agency, they develop, demonstrate, and refine skills that are essential to their learning and growth.

She also used anecdotal notes to document academic skills, her students’ interests and wonderings, and information shared by families and other caregivers pertaining to their children’s interests, strengths, and developing capabilities. Observations of children’s agency supplemented formal and informal assessment tools. Not only did they help Ms. Bailey authentically and strategically assess multiple knowledge and skills across disciplines, they also informed her lesson planning.

Being a Keen Observer of Young Children

Often when we observe children, we watch them with the intent (conscious or not) to evaluate them. Keen observation is different. We are keen observers when we observe children’s capabilities, interests, and relationships as well as where they spend time, what materials animate them, and what kinds of contributions they enjoy making to the classroom community. Replacing our evaluatory eyes with curious ones means we can focus on young children as human beings with interests, desires, struggles, and cultural values. We can then offer even more agency because we know them better and trust them more.

Keen observation comes from the Learning Through Observation and Pitching In (LOPI) research conducted by scholars throughout the world. This research has found that children in many Indigenous communities learn and contribute by observing and giving keen attention to what is going on around them. Visit learningbyobservingandpitchingin.sites.ucsc.edu to see videos of young children using their keen observation and to learn more about LOPI.

Conclusion

While agency is not a prescriptive framework, there are certain markers that are observable and can indicate the breadth and depth of the agentic experiences children are afforded in school. We have learned from partnerships with educators that when they receive support in recognizing and intentionally creating opportunities for children’s agentic learning, they themselves are empowered to offer a wider variety of educational experiences that welcome children’s multiple ways of learning. They become skilled in connecting curriculum to children’s existing knowledge, and they prioritize the development of exploration and critical skills over teacher-centered, standardized, and narrow learning expectations.

As a field, we need to get better at observing, recognizing, and documenting children’s strengths and capabilities. We also need to advocate for and create the types of agentic learning contexts that allow young children to show their full range of capabilities, interests, and knowledge. Instead of constantly trying to “fix” children—especially children of color—we must examine how disparities in systems and bias in ourselves deny young children their agency. Children cannot show and develop a range of talents and skills when they are consistently denied opportunities to move, talk, tell stories, take initiative, create projects, experiment, and work through conflicts. All children deserve to see themselves as capable learners and contributors to their communities.

Photographs: p. 17 © Getty Images; pp. 16, 21 courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Adair, J.K. 2014. “Agency and Expanding Capabilities in Early Grade Classrooms: What It Could Mean for Young Children.” Harvard Educational Review 84 (2): 217–241.

Adair, J.K., & K.S. Colegrove. 2021. Segregation by Experience: Agency, Racism, and Learning in the Early Grades. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Adair, J.K., & S. Sachdeva. 2021 “Agency and Power in Young Children’s Lives: Five Ways to Advocate for Social Justice as an Early Childhood Educator.” Young Children 76 (2): 40-48. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/summer2021/agency-and-power?r=1&...

Bassok, D., S. Latham, & A. Rorem. 2016. “Is Kindergarten the New First Grade?” AERA Open 2 (1).

Blessing, A.D. 2019. “Assessment in Kindergarten.” Young Children 74 (3): 6–13.

Boykin, A.W., & P. Noguera. 2011. Creating the Opportunity to Learn: Moving from Research to Practice to Close the Achievement Gap. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Carr, M. & W. Lee. 2012. Learning Stories: Constructing Learner Identities in Early Education. London: SAGE.

Cervantes-Soon, C.G., E.D. Degollado, & I. Nuñez. 2020. “The Black and Brown Search for Agency: African American and Latinx Children’s Plight to Bilingualism in a Two-way Dual Language Program.” In Bilingualism for All? Raciolinguistic Perspectives on Dual Language Education in the United States, eds. N. Flores, A. Tseng, & N. Subtirelu.199–219. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Darling-Hammond, L., & J. Snyder. 2000. “Authentic Assessment of Teaching in Context.” Teaching and Teacher Education 16 (5): 523 –545.

Early, D.E., U.I. Iruka, S. Ritchie, O.A. Barbarin, D.M. Winn, G.M. Crawford, P.M. Frome, R.M. Clifford, M.B. Howes, D.M. Bryant, & R.C. Pianta. 2010. “How Do Pre-Kindergarteners Spend Their Time? Gender, Ethnicity, and Income as Predictors of Experiences in Pre-kindergarten Classrooms.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25 (2): 177–193.

Gopnik, A. 2012. “Scientific Thinking in Young Children: Theoretical Advances, Empirical Research, and Policy Implications.” Science 337 (6102): 1623–1627.

Helm, J.H., & L. Katz. 2016. Young Investigators: The Project Approach in the Early Years. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

McManus, M.E., K. Payne, S. Lee, S. Sachdeva, A. Falkner, K. Colegrove, & J. Adair. 2019. “Expanding Video Cued Multivocal Ethnography for Activist Research in the Civic Action and Young Children Study.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 50 (3): 348– 355.

Muller, M., E.G. Braden, S. Long, G.S. Boutte, & K. Wynter-Hoyte. 2022. “Toward Pro-Black Early Childhood Teacher Education.” Young Children 77 (1): 44–51.

NAEYC. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents

Paris, D. 2012. “Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Needed Change in Stance, Terminology, and Practice.” Educational Researcher 41 (3): 93–97.

Park, S., L. Sunmin, M. Alonzo, & J.K. Adair. 2021. “Reconceptualizing Assistance for Young Children of Color with Disabilities in an Inclusion Classroom.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 41 (1): 57–68.

Payne, K.A., J.K. Adair, K.S. Colegrove, S. Lee, A. Falkner, M. McManus, & S. Sachdeva. 2020. “Reconceptualizing Civic Education for Young Children: Recognizing Embodied Civic Action.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 15 (1): 35–46.

Payne, K.A., A. Falkner, & J.K. Adair. 2020. “Critical Geography in Preschool: Evidence of Early Childhood Civic Action and Ideas About Justice.” Teachers College Record 122 (7): 1–34.

Souto-Manning, M. 2014. “Making a Stink About the ‘Ideal’ Classroom: Theorizing and Storying Conflict in Early Childhood Education.” Urban Education 49 (6): 607–63.

Souto-Manning, M., B. Falk, D. López, L.B. Cruz, N. Bradt, N. Cardwell, N. McGowan, A. Perez, A. Rabadi-Raol, & E. Rollins. 2019. “A Transdisciplinary Approach to Equitable Teaching in Early Childhood Education.” Review of Research in Education 43 (1): 249–276.

Wright, B.L. 2021. “What About the Children? Teachers Cultivating and Nurturing the Voice and Agency of Young Children.” Young Children 76 (2): 28–32.

Natacha Ndabahagamye Jones is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Texas at Austin. Natacha’s teaching experience as a bilingual and ESL elementary school teacher and as an early childhood teacher guides her research, which focuses on equitable pedagogies, community-rooted practices, and providing sophisticated educational experiences for all young children, especially for communities of color that have historically been marginalized. [email protected]

Amber T. Fowler, MEd, is a current doctoral student in the Early Childhood Curriculum and Instruction Department at the University of Texas at Austin. Amber has taught kindergarten for six years, is studying early childhood teaching practices, and is interested in children’s early childhood experiences. [email protected]

Jennifer Keys Adair, PhD, is professor of early childhood education and director of the Dynamic Innovation for Young Children Collective at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Adair is an expert on the impact of agency and racism on young children’s learning and development. [email protected]