Rainy Day, Let’s Play! Outdoor Learning for All (Voices)

You are here

Playing to Learn in an Urban, Public School: An Introduction to Two Teacher Narratives

Ben Mardell, Maleka Donaldson, and Barbara Henderson, Voices Executive Editors

Briya Public Charter School in Washington, DC, is a two-generation family educational program that serves immigrant families. Young children attend Reggio-inspired early childhood experiences, and their parents receive English literacy instruction and support. At the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, educators at Briya were challenged to continue providing safe, in-person learning for children and their families. They met the challenge with creativity, curiosity, and wonder—engaging with nature and supporting playful learning for both children and staff.

In the following pieces, which were first published in the Fall 2022 online compilation of Voices of Practitioners, Briya early childhood educators reflect on how meeting these challenges led to embracing the benefits of outdoor education and recommitting to a play-based curriculum. In “Rainy Day, Let’s Play! Outdoor Learning for All,” Lena Johnson and Lydia Mackie recount children’s active engagement and learning in Briya’s outdoor classroom spaces, even during rainy weather. Lena has worked in Germany, Spain, South America, and the United States in the field of inclusive education, playful learning, and the connection between nature and play. She holds a doctorate and is the director of early childhood at Briya. Lydia was a classroom teacher and the outdoor curriculum and student support specialist at Briya. She has taught young learners in Istanbul and Washington, DC, and recently completed a master’s degree at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

In “Planning to Play: Empowering Teachers to Empower Children,” Kerstin Schmidt and Noelani Mussman convey the wonder and joy that children and educators experienced when play was the basis of both children’s learning and teachers’ professional development. Kerstin teaches pre-K at Briya. She earned her master’s degree from Pacific Oaks College in Pasadena, California. Before joining Briya, Kerstin taught pre-K and kindergarten in Chicago, in California, and in the DC area. She is an active member of the DC-Project Zero network and has facilitated workshops at NAEYC, Bank Street, and the Progressive Educators Network. Noelani, MEd, is director of professional development at Briya. She has served as a teacher, charter school leader, and early childhood program director in DC, San Francisco, and Baltimore, MD. Previously, she was assistant principal of a dual language elementary charter school, and she launched a national early childhood literacy program site at a community college in San Francisco. She earned her master’s degree from Johns Hopkins University.

Both pieces make clear that it is possible to meet the language and literacy needs of emergent multilingual children and to support their cognitive, social, and emotional development through rich opportunities for play.

Both also reflect an initiative taken over the past two years by the Voices executive editors: we continue to feature teacher research but are doing so alongside teacher narratives; that is, first-person accounts from practicing educators. These two formats—teacher research and teacher narratives—provide valuable and complementary insights into the workings of early childhood settings. Each approach lends new perspectives to understanding the current landscape of early learning and teaching, and each approach foregrounds the insights and wisdom of practicing educators, appreciating them for the knowledge creators and advocates they are.

Indeed, teacher narratives focus on a story that highlights an individual’s lived and felt experience, and the following teacher narratives exemplify the lived and felt experiences of early childhood professionals committed to promoting creativity and agency for every child through playful, equitable learning. To read more about how playful learning can be supported for children of varied social and cultural identities and contexts, visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop/dec2022.

During the pandemic, educators at Briya Public Charter School in Washington, DC, aimed to provide families with a safe, in-person option to continue academic instruction, which led to a decision to move our pre-K program outdoors. Despite the challenges that come with working in an urban environment, we found space for nature play in grassy lawns, gardens, makeshift garden beds, pavement, and a tiny swath of urban forest. Our quest to learn outdoors started off mostly as a logistical challenge. As teachers felt more comfortable with learning outdoors, they began to share reflections about the ways that they were discovering the outdoors with the children. Through these qualitative data, patterns emerged:

- Children seemed calmer during circle time and transitions because they had spent hours in movement and sensory play in the mornings.

- Children ate more at lunch and fell asleep more quickly during naptime, and families shared that they jumped out of bed to come to school in the morning.

- Language and inquiry felt more authentic and child directed as children discovered new textures, living creatures, and natural phenomena.

In this article, we discuss the benefits of children and educators having access to nature. We illustrate how children in our setting joyfully explored the outdoors despite the challenges presented by the weather, incorporating the rain and puddles into their play. We describe teachers’ reflections on how our response to COVID-19 turned into a new realm of unanticipated richness in play, exploration, critical thinking, and wonder in the ever-changing world outdoors.

Nature-Based Learning for Each and Every Child

Our story starts with a common occurrence that many preschool teachers know too well: a rainy day. Rainy days can be some of the most difficult for practitioners. Being stuck indoors requires spending the day managing children’s needs for movement, engagement, and sensory stimulation. But what happens when a change of perspective gives educators and children a sunny outlook on the grayest of days?

E.O. Wilson, the Harvard biologist and naturalist, coined the term biophilia to describe humans’ instinctive draw toward nature. He explains that we have a propensity to look to nature to understand patterns and systems, as well as for emotional and mental well-being. These benefits are jeopardized by our growing disconnection from nature (Wilson 1984). From a developmental perspective, studies show that nature-based education can positively influence children’s prosocial development, physical activity, and language development along with instilling a greater respect for nature (Kuo & Jordan 2019). However, children from racially and ethnically marginalized groups and those from families with low incomes have significantly less access to nature compared to White children or those from families with high incomes (Sprague, Berrigan, & Ekenga 2020). The Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens national survey found similar underrepresentation of students with special needs and dual language learners (Natural Start Alliance et al. 2017).

What happens when a change of perspective gives educators and children a sunny outlook on the grayest of days?

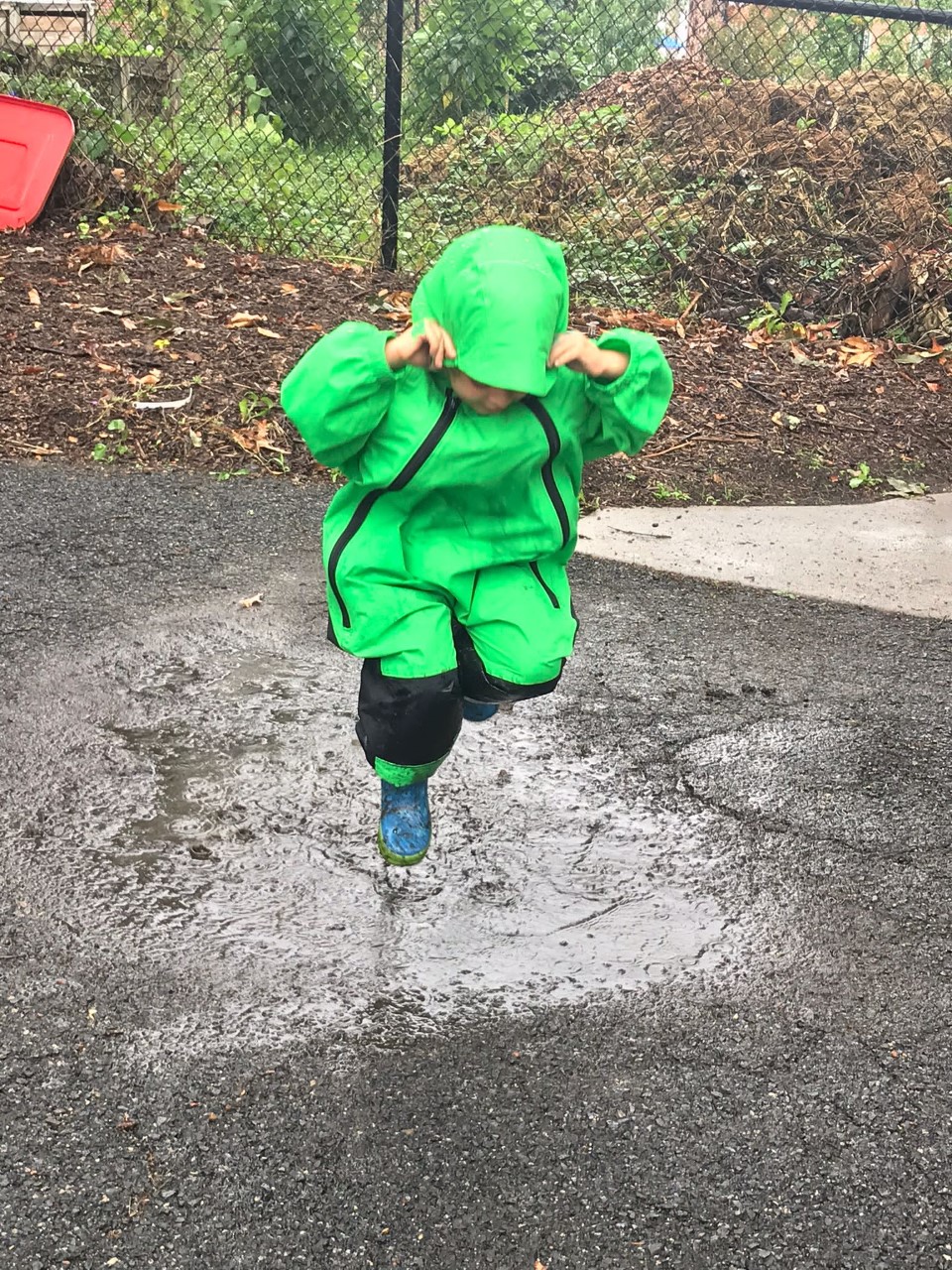

While Washington, DC, may be known for its monuments and parks, it is still very much a city, and green space can be hard to find. To move outdoors for the pandemic, we looked to any patch of grass, sidewalks, and empty parking lots to offer children a way to safely learn outdoors. Along the side of the school buildings and in parking lots, we added gardening beds, log seats and tables, tents, sandboxes, and sensory tables. Briya invested in rainy weather gear as part of our outdoor learning infrastructure, and each class received sets of rainsuits and rain boots in different sizes to fit the growing children in our mixed-age classrooms. Thus, on a rainy day last fall, the children arrived ready to play.

Active Engagement and Learning on a Rainy Day

The sky was gray outside, and the rain pitter-pattered against the windows and pavement on the chilly November day. Families dropped off children at the classroom indoors, where the class gathered for breakfast and a morning circle before spending the rest of the morning outside. Rain boots squeaked at the door while children excitedly hung their backpacks and communicated in English and Spanish: “Did you see the rain?”; “So much rain, yes!” After breakfast, bathroom breaks, and a morning circle, children pulled on their rain boots and rainsuits, ready for the adventures ahead. The teachers and children walked to the parking lot where we set up our outdoor classroom, and immediately four children headed toward the biggest puddle. “How deep is it?”; “Should we jump?” Without hesitation they jumped into the puddle and started to stomp, splash, and laugh at the impact of their bodies on this little body of water. Oliver, who was reluctant to touch water, looked to the other children, their beaming smiles an invitation to play. He ran and jumped into the puddle, his boots landing in firm unison with a splash. “I did it!” he exclaimed proudly.

Silvia and Amelia noticed that the tarp covering the sandbox was filled with water, an impromptu urban lake. Benjamin, who was just beginning to use oral language, knelt quietly next to the sandbox, observing raindrops falling into the water, creating a world of tiny splashes and concentric circles. He picked up a leaf and put it into the water, observing it float on the surface. Isabella quietly joined him, squatting down next to her classmate in this quiet meditation. Other children approached, and they slowly started collecting other materials around them, gathering leaves, sticks, rocks, and acorns. “I need a boat!” Luis exclaimed as others joined the play. “How could we make a boat?” asked their teacher, Alejandra. The children chimed in: “We can use this stick!”; “Or this paper—I can show you.” The children ran to the table under the outdoor tent to fold paper, experimenting with different techniques.

The children responded while they engaged in this rainy world. They showed us how to live in the moment and how we as teachers could slow down and explore with them.

Alejandra watched, offering observations and ideas. The children brought their boats to the water, eager to test them out. Alejandra both narrated their play and asked questions, like the following, to extend their thinking:

- “Ah, I see that you made a boat. How did you make that?”

- “What do you think will happen?”

- “Why do some float and others don’t?”

- “Hmmm, I wonder why some boats float for some time but once they are wet, they sink?”

The children responded while they engaged in this rainy world. They showed us how to live in the moment and how we as teachers could slow down and explore with them. Then the next day, a whole new world awaited us! The puddles and lake were gone, and we found large chunks of ice and a new frozen landscape instead. “What happened?!” children exclaimed, fascinated and ready to play.

The Power of Reflection

Briya has a rich practice of reflection in our daily, weekly, and monthly check-ins. During the first months of learning outdoors, teachers at our four sites shared challenges and tips along with questions and concerns: “Will the children run into the road? What about bathrooms? What about rain?” There were undoubtedly logistical challenges to moving outdoors. But as the logistics fell into place, teachers began to share their surprises and observations about the ways that children interacted with the world. They also noted how much easier it felt to extend their learning: “Is it just me, or do the children seem calmer? Yesterday they watched the ants, and one child wanted to read to them.”; “At our site we are doing a bird study, and they found a nest, and they were trying to guess what kind of bird it would be.”

Briya has a rich practice of reflection in our daily, weekly, and monthly check-ins. During the first months of learning outdoors, teachers at our four sites shared challenges and tips along with questions and concerns: “Will the children run into the road? What about bathrooms? What about rain?” There were undoubtedly logistical challenges to moving outdoors. But as the logistics fell into place, teachers began to share their surprises and observations about the ways that children interacted with the world. They also noted how much easier it felt to extend their learning: “Is it just me, or do the children seem calmer? Yesterday they watched the ants, and one child wanted to read to them.”; “At our site we are doing a bird study, and they found a nest, and they were trying to guess what kind of bird it would be.”

We reflected on the ways we spent rainy days before: Anxious to keep children busy, pre-K teachers dug into their years of experience to offer children back-up activities. They relied on sensory trays, exercise routines, tricycles in spare meeting rooms, and stretching breaks. We sang “Rain, Rain, Go Away” and hoped for drier days.

When Briya moved outdoors, we slowly discovered a shift in our understanding of the possibilities for learning outside the walls of the classroom. Teachers shared observations about rainy days at their respective sites and how they integrated different skills into the moment. Tin cans and raindrops became musical instruments and an opportunity to practice counting: “How many raindrops will fill the can?” In another class, a teacher observed a child using a traffic cone to catch rain off the roof and funnel it into a bucket. This child invited others to help him fill buckets, and they formed an impromptu assembly line to catch rain in buckets and pour it through traffic cones into bigger buckets. This required the children to use knowledge and skills from across developmental domains as they engaged in a game rich in problem solving, communication, and measurement. We reflected that the children seemed to learn just as much from each other as they did from the teachers, and each moment was packed with opportunities for discovery. For practitioners, there was more freedom to discover with the children.

Natural environments engage, inspire, and provoke children in ways that surprise us daily.

We learned to start small. We were first occupied with the logistics of moving outdoors; it took time to become comfortable with finding a routine that worked. Successful outdoor learning involved the participation of the entire school, including families, support staff, teachers, administration, and other stakeholders. For example, families trusted the school to keep their children safe, and the school shared the plan to use rainsuits and rain boots to keep the children dry. With practice, we as practitioners learned to slow down, step back, and listen. As children lead their own play with natural materials, teachers have more time and space to learn from nature as the third teacher. And finally, we learned to embrace these surprises. Natural environments engage, inspire, and provoke children in ways that surprise us every day. While going outside daily is a new and sometimes challenging experience for teachers and parents, seeing the deep play children engage in when outside (with the right gear) is eye-opening and inspiring.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- peruse an archive of Voices articles

- read the Fall 2022 Voices compilation

Photographs: courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Kuo, M., & C. Jordan. 2019. “The Natural World as a Resource for Learning and Development: From Schoolyards to Wilderness.” Frontiers of Psychology 10: 1763.

Natural Start Alliance, Eastern Region Association of Forest and Nature Schools, NINPA (The Northern Illinois Nature Preschools Association), & The Washington Area Nature Preschools Association. 2017. Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens 2017 National Survey. naturalstart.org/sites/default/files/staff/nature_preschools_national_survey_2017.pdf.

Sprague, N., D. Berrigan, & C.C. Ekenga. 2020. “An Analysis of the Educational and Health-Related Benefits of Nature-Based Environmental Education in Low-Income Black and Hispanic Children." Health Equity 4 (1): 198–210.

Wilson, E.O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lena Johnson, PhD, is the director of early childhood at Briya Public Charter School, a two-generation public charter school in Washington, DC. She has worked in Germany, Spain, South America, and the United States in the field of inclusive education, playful learning, and the connection between nature and play. [email protected]

Lydia Mackie, EdM, was a classroom teacher and the outdoor curriculum and student support specialist at Briya Public Charter School. Lydia has taught young learners in Istanbul and Washington, DC, and recently completed a master’s degree at Harvard Graduate School of Education.