An Innocent Question Packed with Opportunity

You are here

As educators, we find ourselves constantly trying to navigate children’s questions. They can challenge our knowledge, perception of reality, beliefs, and lifestyles, and we may find ourselves trying to figure out the best approach to each of these inquiries. I have been in such a situation several times—no matter the country, the spoken language, the school, or the group of children—but it was not until six years ago that one of those questions changed me deeply.

In 2017, I was teaching a beautiful group of 3- and 4-year-olds in Louisville, Kentucky. One day, Kellen, an amazingly curious boy, approached me and asked, “Mrs. Maria, what color are you?” I stopped and sat with him to talk. During that time, we had a powerful conversation about differences in skin tones, countries, and languages. Yes, we were talking about identity! Throughout that day, other children joined the conversation too.

Me: What skin tone do you think you have?

Rebecca: I think I am kinda pink.

John: White?

Olivia: You don’t look white. You look yellowish with pink.

Me: I am from Peru, and in my country, we have different skin tones.

Ellie: Mrs. Maria, my dad is from Greece!

Christopher: And I am from China!

Kellen helped me understand myself during a specific transition in my life. This conversation happened when I was in my second year as an immigrant to the United States, and his question opened the door to understanding this new part of my identity. During those first two years, I filled out paperwork to become a resident (and eventually a citizen) that required me to identify my race and ethnicity, which was a new process compared to my country of origin. I thought, “I am not ‘White’ or ‘Native American.’ I am not ‘African American’ or ‘Pacific Islander.’ ” I did not know what to mark on those forms besides the obvious category of being Hispanic/Latina. I was amazed that such a simple question provoked so many thoughts about myself. My grandma was a White Spanish citizen; the rest of my family was Peruvian, which meant a mix of White Spanish with South American Indigenous origin.

On the other hand, the children at the center had been identified as White: their families were mostly White; their teachers were White; their neighborhood was mostly White. But when we discussed this category in the classroom, the children questioned the meaning behind this concept: Were they all White?; What does “being White” mean?; How does it relate to our concept of a color? As the only Hispanic educator on the team, I was still navigating this category myself and what it meant in this country. I came from a different background, so it was a new world for me to understand.

This preschool center welcomed more than a hundred families who shared similar beliefs and values. Teachers formed and maintained a strong and caring community using a curriculum focused on play, care, and relationships to promote children’s meaningful learning. While understanding diversity was, perhaps, one of the main challenges the center faced, the teachers’ willingness to change and adapt their attitudes and practices to address diversity had been a priority. I felt like I had a voice in the community and that I was embraced, supported, and provided with a safe space to share my thoughts, concerns, and cultural values.

Despite being embraced and included, I still faced many challenges as a member of a “different” community. I was an immigrant trying to find my place as a minority, and I had to prove that I was as capable and knowledgeable as any other member of the group. For the first time, I experienced the concept of otherness. This motivated me to clarify my beliefs, including about the quality of education I received in Peru, my accent, and the challenges I had to face as a bilingual person having uncomfortable conversations about fairness and equity in this country.

Kellen’s question about the color of my skin gave me the strength to talk about myself in an open, caring learning community. However, I was not alone in facing these challenges; I had a group of powerful children who were brave enough to speak up, ask questions, and respect each other. I had a wonderful teacher coleading with me. She listened to my fears, dreams, and concerns, and she encouraged me to share my passion for inclusion and my dream of a world where uncomfortable conversations could be accepted and valued.

After we had further conversations and did more research, Christopher, the child who shared that he was from China, had the confidence to tell his story. He was Chinese and had been adopted by a wonderful family in Louisville. He and I connected through the experience of immigration. For example, we both knew what finding a new home meant. We also both knew how life changes when you find loving relationships in a foreign community while leaving behind a country full of people who are important to you.

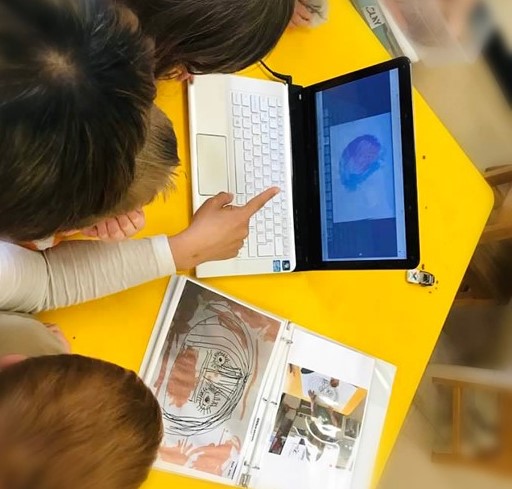

For six months, our class had small-group and whole-group discussions, video sessions with children in Peru, and learning experiences that included creating self-portraits, drawings, paintings, clay sculptures, and compositions with loose parts. We also did internet searches, read, and engaged in other opportunities to develop our complex thinking processes and a sense of belonging in our community. During one session, Christopher found the occasion and space to share about the beautiful moment when he found his American family. He told us how his parents picked him up at the airport, and together, they took a long flight to his new home. I invited his mom to assume an important part in this research on identity. She was beyond excited to share about some meaningful traditions. She and Christopher talked about the Chinese New Year and how they celebrated it at home. They also discussed how festive Beijing looked during this time of year and the symbolism behind dragons. That morning, we all got to know Christopher in a deeper way. We built a stronger relationship with his family, and we meaningfully explored the richness of our cultures.

Once again, the bravery of the children helped me feel brave enough to share my own story and tell them about my own country—how much I missed my family there and about the school I used to work in. One child excitedly requested, “We want to see your old school!” This led to a powerful video session when we connected with a group of Peruvian children who were part of the school where I taught. “Look! They have paint and magnifying glasses just like us!” the children said, noticing the similarities between their schools. During that hour, the children in both classes found their own ways to communicate their thoughts and ask questions to engage with each other. They were able to integrate both Spanish and English in such a natural way that it seemed like they were all bilingual.

Rinaldi (2000) states that teachers have an opportunity to witness and reflect upon the many ways children learn, which involves more than “. . . the use of only one language (the verbal language) . . .” (3). Throughout this exploration, I found certain questions to be as pertinent as ever: How do children in my classroom learn? What are the concepts behind these conversations? What languages can I offer to promote those relationships? If I lack resources to offer, I might just need some time to pause and reflect on how children find their own way to build relationships. Like the day Belle, a 4-year-old child in our class, asked, “Mrs. Maria, what language does Grant use?” Grant was a boy diagnosed with Down syndrome who was learning to communicate through sign language.

Me: Grant uses sign language.

Belle: What is sign language?

Me: It’s another way to communicate while using gestures with your hands and body.

Belle: I wish I could learn sign language to tell him that I love him so much.

I have been deeply touched by these meaningful conversations that represent seeds of understanding and appreciation for each other. Kellen’s innocent question became an opportunity to explore powerful concepts such as identity, culture, self-perception, differences, and similarities that connect us all.

Along with the spaces of dialogue, the materials we used to communicate became a fundamental part of our research on identity. Children were offered multiple tools and techniques that would develop their thoughts and deepen their understanding of powerful concepts. They were exposed to complex learning contexts that would promote exploration and dialogue. Meanwhile, I was inspired by the complexity of their thinking and decided to document every session to make their thinking processes visible. I realized once again that my role as an educator goes beyond teaching a specific set of skills or knowledge. Learning happens all the time, and exploring our social identities is a foundational part of any curriculum.

The children and I shared our explorations and learning with the whole community through discussions and documentation. We realized how important this process was to understand each other and build our community based on anti-bias values and culturally responsive practices (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, with Goins 2020). As educators, we need to make sure that the voices of children and their families are being heard by promoting a safe environment for them to share their heritages and diversity, to ask questions, and to explore the complexity of their social identities, all within an environment built on the foundation of kindness and respect.

Engaging Children and Families in Anti-Bias Practices

Together, the children and I understood each other, our identities, and our place in our community. It was a deeply reflective process that helped me discover three specific ways to engage children and their families in anti-bias practices and to reflect on my identity in my teaching and community contexts.

- Use a variety of materials. As an educator, I see the need to promote the use of a variety of multicultural materials in the classroom to promote a better understanding of diversity around the world. Introducing diverse classroom materials can help children, teachers, and families understand their identities, value their cultures, and develop a deep sense of belonging.

- Create space for dialogue. It is not easy to implement anti-bias practices, but it has positive benefits on children’s development. Therefore, it is crucial to create spaces for dialogue. As Derman-Sparks, LeeKeenan, and Nimmo (2023) state, “Anti-bias endeavors are part of a proud and long educational tradition—one that continues to seek and to make the dream of justice and equality a reality. It happens day by day, and calls on our best teaching, relationships, and leadership skills” (183). As educators, we can promote reflective practices and critical thinking with care and respect when we support children to freely share their thoughts and beliefs. Further, we can document their dialogue, so their ideas are visible and their voices are shared with the community.

- Engage families. It is crucial to engage families and develop spaces where family members can connect and support each other. Families have voices that should be part of the school’s culture, and my role as an educator is to remind them that they are fundamental.

After years of working with children, families, and administrators, I have concluded that talking about identity does not create division. Instead, it builds bridges that connect people in a deeper way. We are all indeed different and valuable, and children are aware of this. They are ready to talk about it and bring important questions to their learning communities. Rather than ignoring children’s questions or pretending they don’t understand, we should respond to their inquiries respectfully and flexibly, creating an atmosphere of kindness and bravery.

Photographs courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Derman-Sparks, L., & J.O. Edwards. With C.M. Goins. 2020. Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Derman-Sparks, L., D. LeeKeenan, & J. Nimmo. 2023. Leading Anti-Bias Early Childhood Programs: A Guide to Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Rinaldi, C. 2000. “The Significance of Being Here Together.” Rechild: Reggio Children Newsletter. Accessed October 24, 2023. reggiochildren.it/assets/Uploads/Rechild-Maggio-2000.pdf

Maria Jose Beteta, MS, is an early childhood coordinator at LEARN, a regional organization in Connecticut. Maria has worked as a consultant, promoting the implementation of culturally responsive practices and the project-based approach. She also supports Hispanic educators throughout the United States.