Framing: How We Think About Our Work

You are here

Being literate in today’s digital world demands a bear-hug-sized embrace of intellectual curiosity and imagination. Curiosity and imagination allow us to envision a world in which people routinely use media ethically and effectively and enable us to see what young children need to learn to make that vision real.

Early childhood educators especially need imagination because when advocates first described media literacy as the ability “to access, analyze, and produce information for specific outcomes,” they mostly had adolescents and young adults in mind (Firestone 1993, 6). Though there have been a few notable efforts to engage primary students in media literacy (e.g., Bazalgette 2010 or ProjectLookSharp.org), we are only beginning to explore which common practices for teaching older children will need to change in order to engage toddlers and preschoolers (see “What to Expect: Media Literacy Is Literacy” below).

At this moment in history, the boundaries of media literacy in early childhood education are fluid, which means there are wide open opportunities to forge new pathways. We are like wilderness scouts. To create new trails, we need a clear idea of where we are headed and also knowledge of the existing landscape—in this case, child development, education, and media. Imagination opens us to visions of new paths, especially as the landscape changes, and we need to adapt.

Like everything we teach, media literacy education is a response to a perceived need. Disagreements over just what that need is have led to a diverse and sometimes contradictory array of practices (Huguet et al. 2019). Understanding the disagreements provides important context for understanding the practice of media literacy education.

This article walks you through key disputes among early childhood professionals, so you can be clear about your own approach and how it influences potential outcomes. It is adapted from Chapter 4 in Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates, which was recently published by NAEYC. The book explores much more about media literacy education for engaging children ages 2 to 7, including the importance of visual literacy, using media literacy skills and knowledge to analyze media effects research, how to lead a media analysis without telling children what to think, and many conversation examples and activity ideas.

What to Expect

Media Literacy Is Literacy

People use the label media literacy to describe a lot of different things. When pared down to its core, media literacy is primarily an expansion of traditional literacy that includes all the ways we communicate today—digital media but also printed books, posters, product packaging, logos, jigsaw puzzles, recorded music, signs, and so much more. Any form of communication that is mediated—with something between the sender and receiver of a message—is media.

Like traditional literacy, media literacy includes learning how to decode symbol systems that allow us to “read” and “write” using multiple forms of media.

Framed as literacy, media literacy includes emotional awareness, ethics, discernment, and complex concepts such as

- epistemology—uncovering the sources of our ideas

- metacognition—awareness of how we know what we know and how we learn

- reason—using evidence and logic to arrive at conclusions

Even young children can engage in these very substantive pursuits, especially if, like traditional literacy, we weave media literacy into nearly everything we teach. In this aspect, media literacy is as much a method as it is a subject area.

Pedagogy as Frame

If you paint or take photographs or videos, you know that the way you frame your subject is important. All media makers use framing to include and exclude information. That makes framing a powerful tool. It can change the way we see the world and the way that others see us.

If you paint or take photographs or videos, you know that the way you frame your subject is important. All media makers use framing to include and exclude information. That makes framing a powerful tool. It can change the way we see the world and the way that others see us.

The concept of framing also applies to thinking. The way we frame an issue or a task influences the way we think about it. When we apply that process to education, we call it pedagogy. Our pedagogy is our approach to teaching—the set of actions that stems from and expresses our beliefs about these aspects of teaching:

- children’s capabilities and vulnerabilities

- the appropriate role of a teacher

- the learning process

- cultural values

- professional ethics

- our general worldview (what we hope the world will be and how we envision children functioning in it when they are grown)

Like all early childhood education, media literacy pedagogy is grounded in the awareness that “early childhood (birth through age 8) is a uniquely valuable and vulnerable time in the human life cycle. The early childhood years lay the foundation and create trajectories for all later learning and development” (NAEYC 2019, 13). As the Annie E. Casey Foundation (2013) aptly explains, “What happens to children during those critical first years will determine whether their maturing brain has a sturdy foundation or a fragile one” (1).

So if everyone agrees that the early years are vital, why are there wildly differing visions for developmentally appropriate media literacy education? The answer is that there are conflicting beliefs about how best to address the growing presence of media technologies in our lives.

At this moment in history, the boundaries of media literacy in early childhood education are fluid, which means there are wide open opportunities to forge new pathways.

Divergent approaches to media are not new. Debates about media harms have accompanied the introduction of every form of mass media throughout recorded history. As British researcher Amy Orben (2020) describes in an insightful overview, there is a recurring panic cycle: A swift rise of a new media form is followed by concerns about the inordinate amount of time youth spend with that new media. This provokes attention from people in power, who fund research into the problem. The research concludes that adults’ preferred media is fine, but the new media that young people use (whatever it is), leads to physical, mental, and/or moral harm. Looking back, we know that previous predictions of doomed generations were mostly wrong. Radio, comic books, dime novels, and the like didn’t destroy humanity. That should provide some comfort to those who fear the effects of today’s digital media technologies. The most sensational claims will almost certainly prove to be unfounded.

That said, we need not abandon legitimate concerns in order to learn from history. As Orben suggests, we can refine research methods to avoid past mistakes (2020).

Current claims about media technologies range from complete moral panic (media will destroy children’s brains and the fabric of society) to media as salvation (there is no harm and, by the way, the particular media I am selling will guarantee children a fabulous future). Not surprisingly, reality is more complex than either of these extremes. This piece’s purpose is not to settle the debate, but rather, to explore how our approach to media influences our practice.

Choosing a Frame for Media Literacy

In a 2019 TED Talk, eminent researcher Sonia Livingstone (2019) observed that digital technologies have “become the terrain on which we are negotiating who we are, our identities, our relationships, our values, and our children’s life chances.” She was speaking about parenting, but her observation applies equally well to early childhood educators.

The stakes are incredibly high, encompassing every aspect of who we are and who we hope our children will be. Our media decisions are not just about media, they are an expression of our deepest anxieties and hopes. So, our choice of pedagogy for media literacy education is not trivial.

It is interesting, then, that historically, when it comes to dealing with media, early childhood education has focused on media effects rather than pedagogy. We will not—and should not—abandon concerns about media in our lives. But in order for media literacy education to be effective, we need to transition from an effects-centered model to one that is centered around teaching and learning.

Our History: A Public Health Paradigm

The pedagogy that has historically dominated early childhood education’s approach to media and children is based in a medical, public health paradigm. In this framing, the paramount need is to keep children safe and healthy, and the essential question is how best to do that. Because health and safety are the goals, a public health prism naturally directs educators’ attention to the ways that media pose a threat to children’s well-being.

Concerns are broad and substantive: materialism, a weakening of democracy, and environmental sustainability, along with an array of conditions that are typically the domain of health professionals. Susan Linn, founder of Fairplay (formerly the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood), cites media use as a cause of childhood obesity, eating disorders, sexualization, youth violence, family stress, depression, low self-esteem, underage drinking and tobacco use, and more (Linn 2010). Proponents see media use as displacing vital activities like physical movement, interacting with real people, and handling three-dimensional objects. In keeping with a medical framing, some pathologize such displacement with labels like “play deficit disorder” (Levin 2013, 35) or “nature deficit disorder” (Louv 2005).

Like most public health initiatives, the public health paradigm is concerned with prevention. Young children need to be protected now, in the crucial years that their brains, bodies, and foundational relationships are developing or, advocates argue, the negative effects of too much media will follow children their entire lives.

For guidance on strategies, educators acting from a public health paradigm primarily turn to medical sources. One familiar example is Caring for Our Children (CFOC), the National Health and Safety Performance Standards Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), together with the American Public Health Association (APHA) and the University of Colorado College of Nursing’s National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education (NRC) (AAP, APHA, & NRC 2019). Its 2019 standards and guidelines—specifically, “Standard 2.2.0.3: Screen Time/Digital Media Use”—recommend that digital media should not be used at all with children younger than 2 and should be used for no more than one hour total (including time at home) with children ages 2 to 5. That single hour must be “high-quality programming,” which the standard defines as free of ads, violence, and “sounds that tempt children to overuse the product.” And this “high-quality” fare must be “viewed with an adult who can help children apply what they are learning to the world around them.”

The standard adds several restrictions for which there are broad consensus and substantial supporting research. No digital media during snacks, meals, and nap time. And no media on in the background (that is, when it’s not the focus of the activity) because “media can be distracting, and reduce social engagement and learning.”

The standards also make recommendations that are not universally accepted, such as treating use of screen media and play (or conversations) as if these are mutually exclusive. Or dismissing entertainment media as always in competition with, rather than part of, family time.

The standards also include this explanatory note, “For the purposes of this standard, “screen time/digital media” refers to media content viewed on cell/mobile phone, tablet, computer, television (TV), video, film, and DVD. It does not include video chatting with family.”

The unmistakable intent of these suggestions is to support the health of young children, but this final note reveals an obstacle that the public health paradigm cannot overcome. Public health education methods only work well when the information that needs to be conveyed and the desired action are simple and concrete.

The Centers for Disease Control’s anti-smoking campaign is a good example: cigarette smoking is likely to kill you, so don’t smoke. There is no need for nuance or a wide array of personalized alternatives. And the evidence of the campaign’s success is all around us. Smoking cigarettes is now banned in nearly all public indoor spaces, and the once common habit is now undertaken by only 15 percent of adult Americans (Blakemore 2015).

But public health education methods fail when the messaging or actions are complex. This is, in part, what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, with official recommendations about masks and vaccines changing as the science and availability of supplies evolved. Spokespeople disagreed in public, and directives applied to different groups of people at different times, leading to confusion even among those who wanted to comply.

Media literacy messaging is similarly complex. In our digital world, where screens are now necessary for many daily routines and social media serve as an online digital commons for political discourse and cultural expression, the simplicity that is necessary for public health messaging does not exist. This forces public health educators into a reductionist approach that doesn’t serve children very well.

The limitations are reflected in the final note of the CFOC standards, which narrows the discussion to digital and screen media and then further limits it to noninteractive viewing (specifically exempting video chatting, for example). The CFOC standards do not address the use of voice assistants, digital play, cameras, audio recorders, or other screen-based media- or art-making tools. And they don’t mention “media literacy,” even though they encourage use of media like books and puzzles, and they recognize that media such as classroom posters can convey stereotypes (CFOC Standard 2.1.1.8). This gap is mirrored in other popular guidelines. For example, neither the widely used Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS) nor recent Head Start guidelines address media literacy at all.

When use of screen media and well-being are positioned as mutually exclusive, the resulting risk assessment is obvious: the risks posed by screen media greatly outweigh any potential benefits. The logical strategy, then, is to limit “exposure,” as if screen time is, to borrow researcher Karen Wohlwend’s skeptical language, akin to toxic radiation (2011). It is a pedagogy of avoidance.

In some versions of the paradigm, this means a total ban. Others, like the CFOC standards, approach screen media more like a drug. Children can benefit from using a proper dose, but too much is dangerous, so adults impose significant limits. And on the infrequent occasions when media are used, adults are always included. Children are never permitted to use media by themselves.

To find “high-quality programming,” those who act from a public health paradigm rely on children’s media researchers to determine the efficacy of the media “drug.” Series, apps, or games that demonstrate positive results are differentiated from potentially problematic entertainment fare, which is to be avoided. This limits acceptable children’s media choices to those that are noncommercial and researcher-approved.

In a public health paradigm, if there are media literacy lessons at all, they typically are designed to inform children about media dangers, usually via direct instruction. The consistent message to children is that there are always better ways to spend their time than to use screens.

The Education Paradigm

The challenge of the public health paradigm for media literacy educators is not its concerns about media effects. Rather, the challenge is that counting screen minutes is not an education strategy. It doesn’t help children develop media literacy skills, knowledge, or habits.

Everyone agrees that keeping children safe and healthy is a basic, nonnegotiable responsibility, even when we disagree about the exact nature of the risks or about how much risk is acceptable. The two paradigms are not stand-ins for opposing sides of the debates over media effects. Actually, most media literacy educators and advocates are involved in media literacy because we believe it is important to pay significant attention to the role of media in our lives. Given the prevalence of media, it would be foolhardy to do otherwise.

In the United States, nearly all children 8 and under live in a home with at least one television and mobile device. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, screen time estimates for this age group averaged about two-and-a-half hours per day (Rideout & Robb 2020).

In the public health paradigm, these observations manifest as the argument that children are already spending too much time in front of screens, so let’s not add to the problem by using screen media in child care settings or primary school. In an education paradigm, the ubiquity of screens (and other media) is exactly what makes the integration of media essential.

Given the reality that media are integral to our culture, it seems odd to expect educators to respond by intentionally excluding media from our work. Just as it would be absurd to suggest that we could help children become print literate by keeping them away from books, it is counterproductive to suggest that we can help them become media literate by keeping them away from screen media. That is why an education lens shifts the discussion from if we should use media (or for how many minutes) to curriculum-based decisions about how, what, when, and why. It is what the NAEYC and Fred Rogers Center position statement on technology calls “intentional use” (2012, 5).

This shift also changes how we evaluate our work. In a public health approach, success is measured by how well adults keep children away from screens. An education approach measures children’s progress. It starts with the goal of creating a media-literate society and asks what skills and knowledge are needed to reach that goal. Success is determined by children’s acquisition of the knowledge and skills that we identify as appropriate for their developmental level.

The education frame accepts that no matter the choices we might wish families and care providers would make about screens, nearly all children are using media technologies, and they will continue to use them with or without us. From an education vantage point, it is better for children to use devices with us. Otherwise, their technology habits are likely to come from marketers, peers, or others who may not share our expertise or our concern for children’s well-being. So, while a health frame says brains develop better if we wait to introduce screen media until children are older, the education paradigm says that media, used appropriately, can open up new worlds and nurture healthy brain development. Besides, if we want to help children establish healthy habits, it does not make sense to wait until behavior patterns are entrenched. Asking children to unlearn bad habits is harder than helping them establish good routines in the first place.

The paradigms also view children’s essential nature differently. A public health frame casts children as vulnerable to harmful influences, including media, so little ones are given no independent opportunities to use media the way they might independently play with blocks or dolls.

The education frame agrees that young children are uniquely vulnerable but responds by asking educators to help children gradually build the skills and knowledge they need to make them less so. The foundational assumption of the teaching-learning process assumes that children are essentially capable and that educators help children gain a sense of independence and control by providing opportunities to apply what they have learned. It is impossible to provide those opportunities if your primary goal is to keep children away from media. Our views of children’s nature always translate into practice.

The education paradigm relies on a constructivist model in which adults build on the skills and knowledge that children already possess. In contrast, the job of a public health educator is to transmit information, so lessons often are grounded in a “sage-on-the-stage” or “banking” model, with adults telling children (who are assumed to know little or nothing about media) what to think.

For example, in one common lesson using a health frame, an adult explains to children that advertisers are fooling them. The activity positions adults as the media interpreters and children as fools. Children learn that they cannot trust their own judgment (because they have been fooled) and that they cannot ever trust advertisers. On the surface, that might seem like an important message, but it turns out to be a problem when children encounter public service announcements that we want them to trust (like following rules about masks and social distancing during a pandemic).

Educators avoid those outcomes by changing the language. They let children in on advertisers’ “secret code” by teaching clues that children can look for to find out what an ad might really be saying. This positions children as capable of analyzing ads for themselves and begins to give them the skills to do so. A small shift in the way we frame a lesson can make a huge difference in what children learn, not only about the topic, but also about themselves. It is not that we do not teach about advertising or explain that advertisers are more likely to be serving their own rather than children’s best interests. It is that when we use an education frame, we do it differently. How we teach is as important as what we teach.

One of the most striking differences between the paradigms is what they mean by the word “media.” In a public health frame, media nearly always refers to electronic screens. In an education frame, the task is literacy the way that Paulo Freire conceived it—reading and writing the word and the world. In a child’s world, media are not restricted to screens.

The education paradigm’s approach to screen use flows from there. It includes providing children with opportunities to think more deeply about the media they routinely encounter—including screen media that wouldn’t qualify as “high quality” or “educational.” If it is part of their world, it is important to create spaces where we can help them grapple with it.

This is particularly true for little ones, who do not automatically apply information learned about one thing to another. If all we ever model is analyzing books, then we make it seem like thinking deeply about other media is unimportant. If we exclude screens, we send exactly the opposite of our intended message that it is important to question all media, perhaps especially screen media.

Increasingly there is also a concern that the term “screen time” is not meaningful anymore (for example, see Daugherty et al. 2014; Reeves et al. 2019; Strauss 2019; Whitlock & Masur 2019). Because we now do so many different things with screen technologies, the phrase is too broad to be scientifically or practically helpful. Media scholars Sonia Livingstone and Alicia Blum-Ross add that measuring time spent “may work in the field of health, where less sugar or more exercise is generally useful advice. But in relation to digital technologies, where neither less nor more is the obvious answer in a thoroughly digitally mediated age, a different approach is needed” (Livingstone & Blum-Ross 2020, 44).

As the NAEYC and Fred Rogers Center position statement on technology puts it, “Not all screens are created equal” (2012, 3). What children are actually doing with media technologies is a much more salient variable than time spent. Effective education is not about counting screen minutes; it is about making screen minutes count. Even the media policy of the AAP (2016), often cited to justify limits on media use, calls for media literacy education for children ages 5 and older, recommending that pediatricians “advocate for and promote information and training in media literacy.”

Who Are We in This Moment? Who Do We Want to Be?

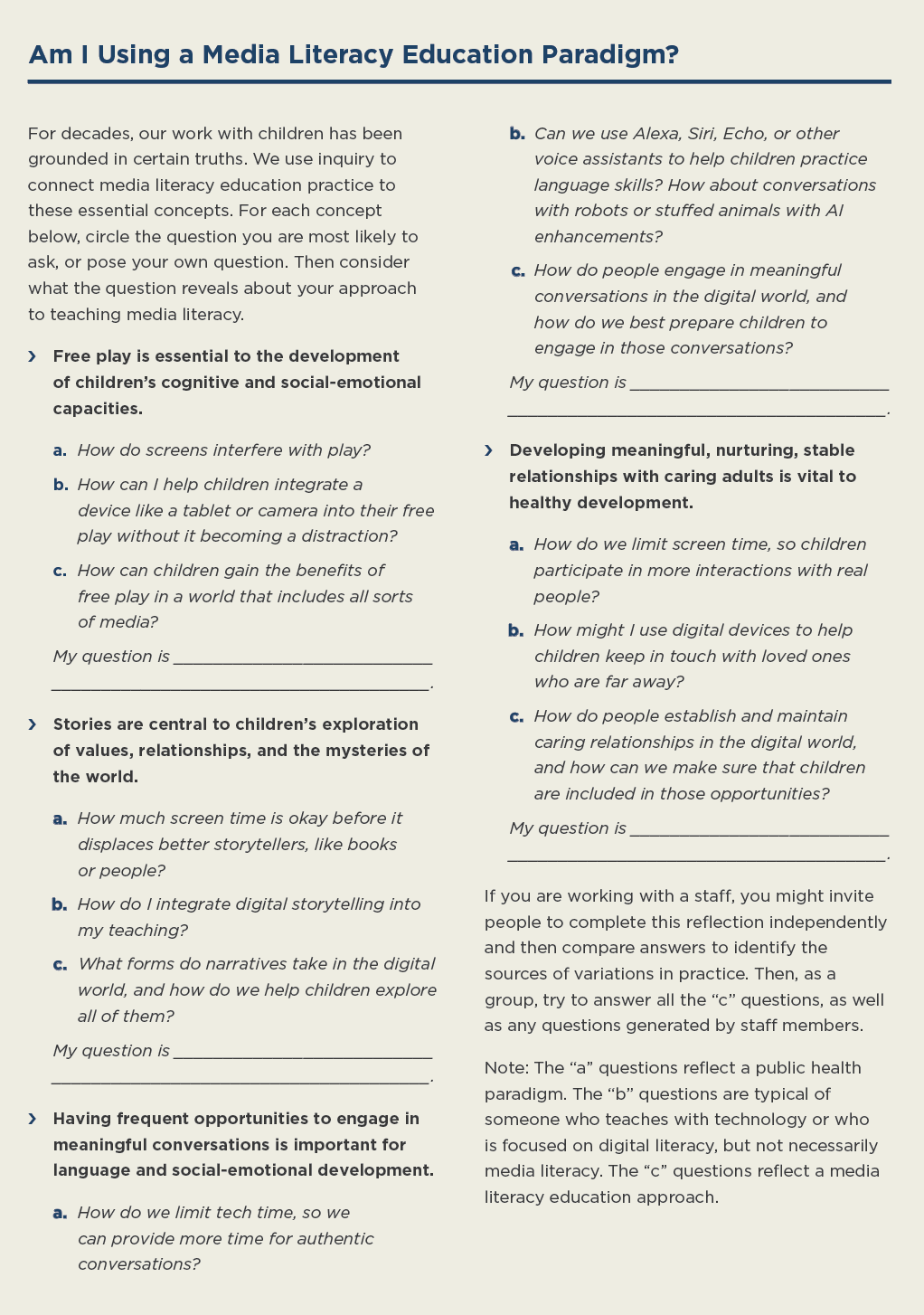

The frame we choose influences which parts of ourselves we bring to the task of teaching media literacy. (See “Am I Using a Media Literacy Education Paradigm?” below.)

We can enter the relationship from a place of anxiety about media, but that means taking the risk that our guilt and apprehensions seep into the design of teaching practices, even unintentionally.

It is exhausting to be in a constant state of alertness, thinking that we must police media use because we worry that every minute of screen time puts children in greater peril. Play is out of the question because in the dualism of a public health paradigm, authentic play—which is healthy—happens only separate from screens—which are unhealthy. When our practice is infused with anxiety, media literacy education is not much fun, and neither are we.

We have a responsibility to challenge media that make it harder to raise healthy, ethical, engaged children. But we also have a responsibility to make sure that we aren’t just imposing our tastes or preferences on those who do not share them.

An education frame asks us to approach the task differently. It requires us to bring the parts of ourselves that are creative and hopeful, even playful, as we craft activities that empower children through skill building. In an education paradigm, media literacy activities invite a sense of wonder and exploration, and we share in children’s amazement and delight as they master new skills or understand important ideas for the first time. It is easy for our joy to overshadow whatever anxiety we might feel.

Effective early childhood education is based on cultivating a positive relationship with each individual child. Barriers that prevent children from sharing with us significant aspects of their daily lives and cultures—including media—can sabotage that process.

The child who comes into our care with a favorite TV character emblazoned on their backpack or t-shirt is sharing with us an important part of their identity. Likewise, a child who bonds with a parent—especially a noncustodial parent—by playing a video game or watching sports or movies on TV may be eager to tell stories about that media experience as a way to share a significant aspect of their life with us. Same thing with a child whose immigrant family uses digital technologies to provide hard-to-find daily lessons that strengthen family ties by teaching native language, religion, or cultural traditions (Livingstone & Blum-Ross 2020). If we respond to these screen-based activities with disapproval instead of curiosity, we make it harder to develop a trusting relationship.

Television shows, songs, movies, and games function as cohort markers. In later years, they serve as common ground, allowing strangers to bond over shared memories of favorite characters or music. When early childhood educators signal that discussions of media are off-limits, we risk shutting out conversations that can be an important conduit for connection.

This is not about staying silent in the presence of danger or surrendering our professional judgment. We have a responsibility to challenge media that make it harder to raise healthy, ethical, engaged children. But we also have a responsibility to make sure that we aren’t just imposing our tastes or preferences on those who do not share them.

As media scholar David Buckingham (2011) has pointed out, often objections to particular media are more about asserting a moral authority based in class privilege—and I would add racial and religious privilege—than any real proof of harm. Before we act on our instinct to protect children against media that we find troubling, we need to pause and be clear that we aren’t simply replicating the power dynamics of existing social structures or imposing our own cultural preferences on families whose cultures differ from our own.

Conclusion

Media literacy education invites us to bring our best selves to the table. It provides a way to act on our concerns about media by engaging as a guide rather than in the role of compliance officer or judge. Being a guide allows us to strengthen relationships by welcoming and cultivating children’s media-related questions and conversations, and it grows children’s skills in the process. The book Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates provides examples of what that looks like in practice.

This article is excerpted from NAEYC’s recently published book Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates. To read more about the book, visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/books/media-literacy.

This article is excerpted from NAEYC’s recently published book Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates. To read more about the book, visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/books/media-literacy.

Photographs: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics) Council on Communications and Media. 2016. “Media Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents.” Pediatrics 138 (5): e20162592.

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics), APHA (American Public Health Association), & NRC (National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education). 2019. Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs. 4th ed. Itasca, IL: AAP. nrckids.org/files/CFOC4%20pdf-%20FINAL.pdf.

Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2013. The First Eight Years: Giving Kids a Foundation for Lifetime Success. Policy report. Baltimore: Annie E. Casey Foundation. aecf.org/resources/the-first-eight-years-giving-kids-a-foundation-for-lifetime-success.

Buckingham, D. 2011. The Material Child: Growing Up in Consumer Culture. Malden, MA: Polity.

Bazalgette, C., ed. 2010. Teaching Media in Primary Schools. London: Sage & Media Education Association.

Daugherty, L., R. Dossani, E.-E. Johnson, & C. Wright. 2014. “Moving Beyond Screen Time: Redefining Developmentally Appropriate Technology Use in Early Childhood Education.” Policy brief. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR673z2.html.

Firestone, C. 1993. “Introduction.” In “Media Literacy—A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy,” P. Aufderheide. Proceedings of the Aspen Institute National Leadership Conference. eric.ed.gov/?id=ED365294.

Huguet, A., J. Kavanagh, G. Baker, & M.S. Blumenthal. 2019. Exploring Media Literacy Education as a Tool for Mitigating Truth Decay. Report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3050.html.

Levin, D.E. 2013. Beyond Remote-Controlled Childhood: Teaching Young Children in the Media Age. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Linn, S. 2010. “The Commercialization of Childhood and Children's Well-Being: What Is the Role of Health Care Providers?” Paediatrics & Child Health 15 (4): 195–97.

Livingstone, S. 2019. “Parenting in the Digital Age.” Talk presented at TEDSummit 2019 in Edinburgh, Scotland. ted.com/talks/sonia_livingstone_parenting_in_the_digital_age.

Livingstone, S., & A. Blum-Ross. 2020. Parenting for a Digital Future: How Hopes and Fears About Technology Shape Children’s Lives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Louv, R. 2005. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

NAEYC. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/resources/position-statements/equity.

NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media. 2012. “Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8.” Joint position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. NAEYC.org/resources/topics/technology-and-media/resources.

Orben, A. 2020. “The Sisyphean Cycle of Technology Panics.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 15 (5): 1143–57.

Reeves, B., N. Ram, T.N. Robinson, J.J. Cummings, C.L. Giles, J. Pan, A. Chiatti, M. Cho, K. Roehrick, X. Yang, A. Gagneja, M. Brinberg, D. Muise, Y. Lu, M. Luo, A. Fitzgerald, & L. Yeykelis. 2019. “Screenomics: A Framework to Capture and Analyze Personal Life Experiences and the Ways that Technology Shapes Them.” Human-Computer Interaction 36 (2): 150–201.

Rideout, V., & M.B. Robb. 2020. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight, 2020. Report. San Francisco: Common Sense Media. commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/2020_zero_to_eight_census_final_web.pdf.

Strauss, E. 2019. “Why We Should Stop Calling It ‘Screen Time’ to Our Kids.” CNN Health, November 14. cnn.com/2019/11/14/health/screen-time-rename-parenting-house-wellness-strauss/index.html.

Whitlock, J., & P.K. Masur. 2019. “Disentangling the Association of Screen Time with Developmental Outcomes and Well-Being: Problems, Challenges, and Opportunities.” JAMA Pediatrics 173 (11): 1021–22.

Wohlwend, K.E. 2011. “Constructing the Child at Play: From the Schooled Child to Technotoddler and Back Again.” Paper presented at the National Council of Teachers of English Annual Convention, in Chicago, IL.

Faith Rogow, PhD, is an independent scholar and longtime media literacy education advocate and innovator. She has written or coauthored a number of books and articles, most recently Media Literacy for Young Children: Teaching Beyond the Screen Time Debates (NAEYC 2022). She also occasionally blogs as the Media Literacy Education Maven at TUNE IN, Next Time. You can find a link to the blog and also contact information on her website: InsightersEducation.com. Comments welcome.