Rocking and Rolling. Sharing Our Calm: The Role of Coregulation in the Infant-Toddler Classroom

You are here

In the infant room, Mateo begins to cry as he tries to roll over and gets “stuck” on his tummy. He lifts his head and makes eye contact with his teacher, Camila. “Oh boy, you’re having a tough time getting onto your back. Let’s see what we can do.” Camila gently helps Mateo roll onto his back. “There! All better!” Camila offers Mateo a rattle, rubs his belly, and stays with him until he is calm again.

In the toddler room, teacher Jevon is watching while Carlee attempts to turn the crank on the jack-in-the-box. She tries again and again, getting increasingly frustrated. Jevon stays close and says, “It’s tricky to turn the crank, isn’t it? Can you use this hand to hold the box while you turn with the other hand?” As she tries unsuccessfully again and pushes the jack-in-the-box away angrily, Jevon says: “I see you’re feeling a little frustrated. Would you like a hug?” Carlee folds herself into his arms for a quick cuddle. Jevon takes a few deep, slow breaths and notices that Carlee’s breathing is slowing down too. She steps away, sits down, and pulls the toy toward her again.

Picture any of a dozen challenging moments across an average day: Two toddlers are overwhelmed with sharing at the train table. A 6-month-old needs a diaper change. An 11-month-old sobs at drop-off, watching their grandma leave for the day. A child falls and bumps their knee on the playground. A toddler throws a block from the tower that just collapsed. Children encounter a range of challenges and move through the whole spectrum of emotions across an average day—turning to the adults in their world, especially their teachers, for help managing and coping with their big feelings and experiences.

Babies are born with little to no ability to regulate their emotional states. From birth to 3 years, they depend on the caregiving adults in their lives to soothe and calm them. The role of these adults is to remain attuned to a child’s early communications and respond sensitively, using their own voice, touch, and gaze to help the child cope with the intensity of their emotions (Housman 2017; Mänty et al. 2022). Through this process of “sharing our calm”—or coregulation—adults support babies and toddlers to begin understanding, expressing, and controlling their feelings and behaviors over time (Gillespie 2015).

One can think of coregulation as a precursor to self-regulation, or the ability to manage feelings, thoughts, and behaviors independently. This is because the development of self-regulation depends on very young children’s access to the predictable, responsive, and supportive relationships of a trusted adult (Housman 2017; Rosanbalm & Murray 2017; Mänty et al. 2022). These adults—who include family members and early childhood educators—play a critical role in supporting babies’ and toddlers’ regulatory capacity through everyday comfort and soothing.

The ability to regulate one’s emotions is foundational for healthy development and functioning (Paley & Hajal 2022). Studies show that people who demonstrate self-regulation as children tend to go on to enjoy higher incomes, better health, and greater life satisfaction (Schunk et al. 2022). Very early childhood is a particularly important time in the development of children’s emotion regulation because the foundation for this capacity is laid during the first three years. Young children mature from being highly dependent upon coregulation with caregivers toward an increasing capacity to manage their own emotional states (Paley & Hajal 2022).

Keeping Calm to Share Our Calm

Adults can help children build a foundation of self-regulatory skills (Murray et al. 2015) in three broad ways: through relational support, environmental support, and learning experiences focused on self-regulation. (See “Strategies for Coregulation” below.) Indeed, coregulation is so important for a child’s healthy development that it is considered a research-based intervention for enhancing self-regulation during early childhood (Murray, Rosanbalm, & Christopoulos 2016).

However, in order to consistently offer coregulation to children, programs need to ensure that teachers receive nurturing support for their own regulatory capacity and well-being. Coregulation requires that caregiving adults are able to manage their emotions effectively and constructively. Unless we find our own calm, we can’t share it with children.

Learning to stay centered during stressful caregiving moments is challenging. It helps when teachers have familiar and practiced tools they can immediately access in those moments. The better adults are at noticing and managing their own emotional states, the more effective they become at coregulating with babies and toddlers.

Coregulation requires that caregiving adults are able to manage their emotions effectively and constructively.

Strategies for Coregulation

Infant and toddler teachers can help children manage their big feelings and return to a state of calm in three broad ways (Rosanbalm & Murray 2017; Pahigiannis, Rosanbalm, & Murray 2019).

Relationally:

- Get to know each child as an individual. Each baby or toddler has a different temperament (which includes qualities like emotional intensity and frustration tolerance). Educators can observe children to learn how they express a range of feelings (including distress) and to discover their different preferences for soothing.

- Understand that each child is part of a family and a community. Talk with family members about children’s temperaments and the strategies they use to calm their children.

- Use a calm voice and gentle touch to comfort babies and toddlers. Rock, hold, and cuddle them, and slow your own breathing to help them return to a regulated state.

- Name children’s feelings (“You are so disappointed that it’s raining and we can’t go outside.”).

- Offer a “lovey” to cuddle (for children 1 year and older).

Environmentally:

- Use daily routines to provide a sense of safety and consistency in the environment.

- Create a place in the learning setting where children can go when they feel overwhelmed, like a “comfort corner” or “peace tent.”

- Ensure infants and toddlers have access to regular, active play.

- Provide access to sensory experiences that can be calming and regulating to children (infant massage, textured toys, sand and water play, art experiences, music play).

Experientially:

- Ensure all teaching staff understand that aggressive behaviors are normal and expected for toddlers. Agree upon a consistent response to behaviors such as hitting or biting that helps children learn more appropriate ways of expressing their feelings and needs. (See “Understanding and Responding to Children Who Bite” for more information.)

- Provide experiences that help children learn to recognize and name a range of emotions.

- Model regulatory strategies, like taking deep breaths, to help children calm themselves (see zerotothree.org/resource/mindfulness-practices-for-families for resources).

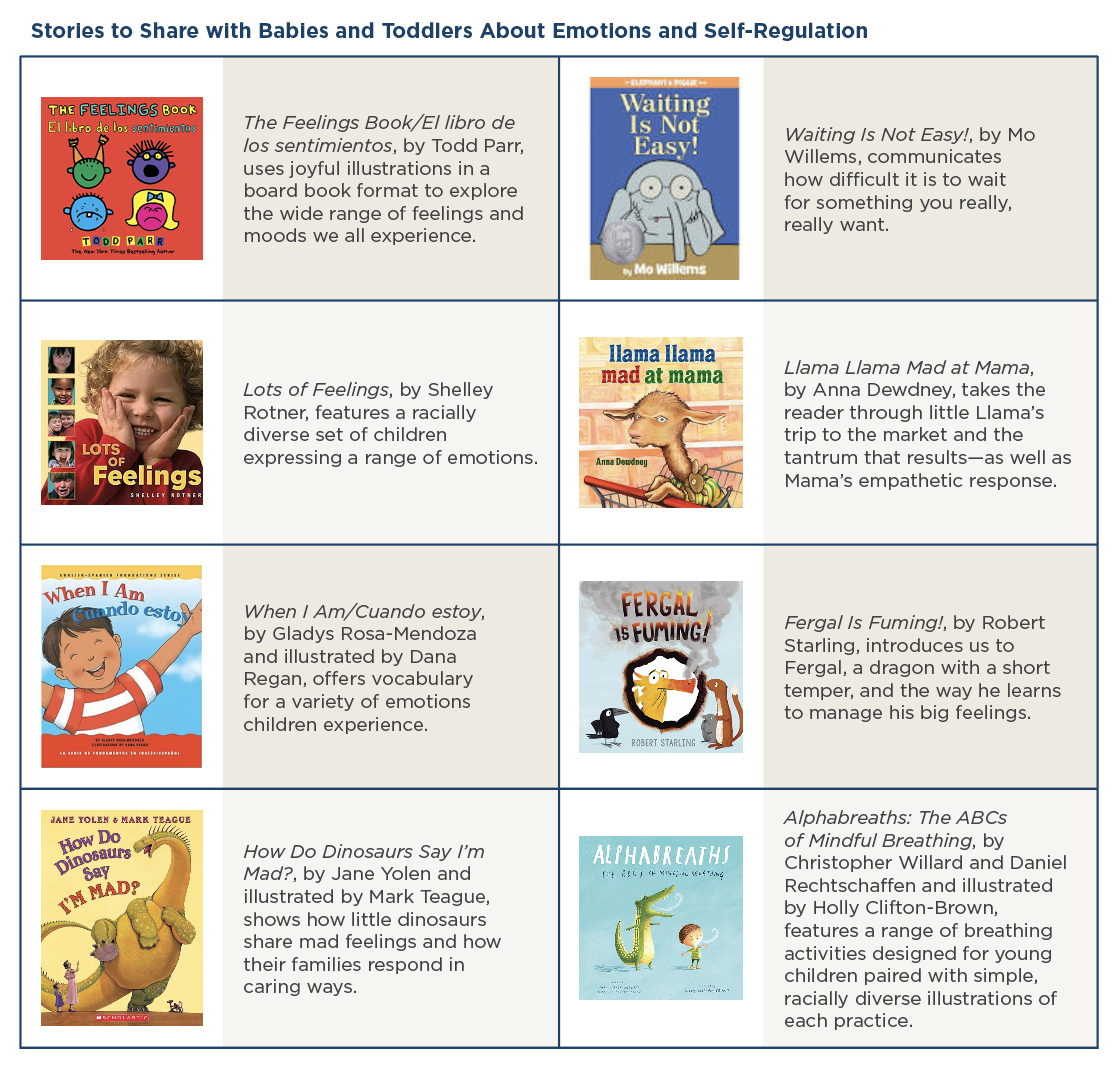

- Incorporate songs, oral storytelling, and children’s literature that focus on themes of emotional awareness and self-regulation (see “Stories to Share with Babies and Toddlers About Emotions and Self-Regulation” at the end of this article). Also consider using social stories to prepare children for new or challenging experiences, such as sharing, resolving peer conflicts, or preparing for a fire drill or field trip. These stories clearly describe important parts of a social activity or event, including what might happen, how the child might feel, how others might feel or respond, and appropriate behavior expectations (Office of Head Start 2023).

What Does This Practice Look Like?

First, early childhood educators should pause and notice their feelings, paying attention to what rises up: anger, frustration, helplessness, isolation, stress, or being overwhelmed. Educators can scan their bodies to notice where they sense stress or tension. It is also helpful to consider basic needs: Are they tired, hungry, or thirsty?

Next, teachers can take action by doing something to care for themselves in the moment: Take three deep breaths. Shake out the tension in their shoulders. Have a glass of water (besides hydration, drinking water forces us to breathe slowly through our nose, which promotes calming). In especially tough moments, a teacher might ask their coteacher or assistant to take over while they recenter.

Finally—once the teacher is calm—they can help the child calm and regulate. They might cuddle the child, stay close while the child cries, rub the child’s back, or rock them and sing a song.

This process describes how mindfulness can be used in early education settings. Mindfulness allows teachers to be aware of what they are sensing and feeling without judgment (ZTT 2023). It has a role in early childhood education because it helps professionals attune to children’s communications and needs, and it gives them tools for staying focused, present, and compassionate with children. A mindfulness practice helps teachers develop the skills needed to regulate their own emotions effectively in tense or stressful situations. These capacities help professionals offer young children access to a coregulation partner, or someone children can trust to help them return to a regulated state when their emotions are overwhelming.

Emerging research indicates that mindfulness practices support early childhood teachers by offering them concrete strategies to be more present and less emotionally reactive and exhausted at work (Hatton-Bowers et al. 2021; Hatton-Bowers et al. 2022). Mindfulness and self-compassion practices also contribute to early childhood educators’ abilities to create and maintain high-quality classroom environments and supportive relationships with challenging children (Jennings 2014). Making mindfulness a routine part of the day promotes overall well-being and increases the likelihood that these practices will be “top of mind” during stressful moments.

Conclusion

When infant-toddler educators help babies and young children coregulate, children learn that their upset feelings don’t last forever. They learn that they will feel calm again with the help of the trusted adults in their world. Over time, these nurturing responses from teachers and family members also help children learn ways to calm themselves during stressful moments. Supporting children in this way builds a strong foundation of emotional regulation, which is a gift they take with them into each new room they enter for the rest of their lives.

Think About It

- Who do you turn to when you are overwhelmed? What does this person do to support your ability to return to a calm state?

- Reflect on your ability to regulate your own thinking and emotions. How does it change across the day? What are some of the situations or events that influence your ability to regulate your emotions?

- Think about a time you noticed a baby’s or toddler’s emotional cues or communications. How did you use these as an opportunity to coregulate?

- How might the quality of the relationship you share with a child influence your ability to engage in coregulation?

- What are some different strategies you use to help children calm themselves? How do these strategies change as children grow?

Try It

- Take a few minutes each day to be fully present with each child in your classroom. Notice their individual cues and ways of communicating. What times of the day and what activities or routines appear to be most challenging for them? Ask family members how they observe their children communicating needs (and how they respond).

- Share information with families about coregulation strategies that you have found effective with their children in the learning setting. Ask what families do at home to comfort and soothe their children.

- Use feelings words and share stories about emotions with babies and toddlers. Narrate how you are managing your own feelings: “I feel so frustrated that I spilled the milk! Oh dear! I’m going to take a deep breath and then get a paper towel.”

- Ask a colleague to observe you with two different children at two different times of day. What coregulation strategies did you use? How was your approach the same with each child or different? What might these observations tell you about these children and your relationship with each of them?

- Try including a mindfulness practice in your daily routine for a week or two. Notice how this practice impacts you: Do you feel calmer? More focused? Less stressed? Do you feel more prepared to respond to children’s emotional cues and communications?

Rocking and Rolling is written by infant and toddler specialists and contributed by ZERO TO THREE, a nonprofit organization working to promote the health and development of infants and toddlers by translating research and knowledge into a range of practical tools and resources for use by the adults who influence the lives of young children.

Photographs: courtesy of CaShawn Thompson

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Gillespie, L. 2015. “It Takes Two: The Role of Coregulation in Building Self-Regulation Skills.” Young Children 70 (3): 94–96.

Hatton-Bowers, H., C. Clark, G. Parra, J. Calvi, M. Yellow Bird, et al. 2022. “Promising Findings that the Cultivating Healthy Intentional Mindfulness Educators’ Program (CHIME) Strengthens Early Childhood Teachers’ Emotional Resources: An Iterative Study.” Early Childhood Education Journal 51 (7): 1291–1304.

Hatton-Bowers, H., E.A. Virmani, L. Nathans, B.A. Walsh, M.J. Buell, et al. 2021. “Cultivating Self-Awareness in Our Work with Infants, Toddlers, and Their Families: Caring for Ourselves as We Care for Others.” Young Children. 76 (1) 30–34.

Housman, D.K. 2017. “The Importance of Emotional Competence and Self-Regulation from Birth: A Case for the Evidence-Based Emotional Cognitive Social Early Learning Approach.” International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy 11. ijccep.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40723-017-0038-6#citeas.

Jennings, P.A. 2014. “Early Childhood Teachers’ Well-Being, Mindfulness, and Self-Compassion in Relation to Classroom Quality and Attitudes Towards Challenging Students.” Mindfulness 6 (4): 732–43.

Mänty, K, S. Kinnunen, O. Rinta-Homi, & M. Koivuniemi. 2022. “Enhancing Early Childhood Educators’ Skills in Coregulating Children’s Emotions: A Collaborative Learning Program.” Frontiers in Education 7. doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.865161

Murray, D.W., K.D. Rosanbalm, & C. Christopoulos. 2016. Self-Regulation and Toxic Stress Report 4: Implications for Programs and Practice. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Murray, D.W., K. Rosanbalm, C. Chrisopoulos, & A. Hamoudi. 2015. Self-Regulation and Toxic Stress: Foundations for Understanding Self-Regulation From an Applied Developmental Perspective. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Office of Head Start. 2023. Social Stories. eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/children-disabilities/article/social-stories.

Pahigiannis, K., K. Rosanbalm, & D.W. Murray. 2019. Supporting the Development of Self-Regulation in Young Children: Tips for Practitioners Working with Toddlers in Classroom Settings. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Paley, B., & N.J. Hajal. 2022. “Conceptualizing Emotion Regulation and Coregulation as Family-Level Phenomena.” Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 25 (1): 19–43.

Rosanbalm, K.D., & D.W. Murray. 2017. Caregiver Coregulation Across Development: A Practice Brief. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US. Department of Health and Human Services.

Schunk, D., E.M. Berger, H. Hermes, K. Winkel, & E. Fehr. 2022. “Teaching Self-Regulation.” Nature Human Behaviour 6 (12): 1680–90.

ZERO TO THREE. 2023. Mindfulness Toolkit or HealthySteps Specialists. Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE.

Rebecca Parlakian MA Ed, is senior director at ZERO TO THREE, where she leads a project portfolio on child development, parenting, and high-quality

teaching. She has coauthored five curricula, including the Early Connections parent café curriculum and Problem Solvers, an early math curriculum. Rebecca holds a master’s degree in infant/toddler special education from George Washington University. [email protected]