Leading an Early Childhood Team Through the Quality Improvement Process

You are here

Quality early childhood programs have long been linked to positive outcomes for children (Jancart et al. 2021; Schoch et al. 2023). However, the path to achieving national accreditation or a high-quality rating from a state Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) is not easy. It requires careful planning, intentional practices, and strong leadership skills.

As a former teacher, center director, and early childhood education trainer and coach, I have experienced this process firsthand. As a teacher, I participated in compiling a portfolio and had an assessor observe my classroom. In my role as coach and trainer, I helped teachers set quality improvement goals and work toward meeting them. As a center director, I guided my staff through the accreditation and quality improvement process. In this article, I highlight strategies that leaders in small- to medium-size, birth-to-5 settings can tap to lead their teams through this process.

Reasons to Pursue Quality

Engaging in accreditation or a state’s Quality Rating and Improvement System can be one of the most rewarding tasks an educator undertakes. It helps to support and validate early childhood education as a profession (Goffin et al. 2015); it also grounds a program in quality standards set by state systems (NCECQA, n.d.) and those outlined in NAEYC’s foundational documents, including its standards and assessment items for early learning programs (2022). By participating in quality improvement efforts, programs help to ensure that

- children benefit from high-quality learning environments, curricula, and qualified and supported staff

- families benefit from programs that recognize the value of reciprocal partnerships around children’s education and care and that honor the strengths, interests, and experiences of all learners and their families

- teaching staffs benefit from professional development and other supports as well as effective leadership and management practices

- communities benefit from having consistent, high-quality child care available for families (Great Start to Quality, n.d.; Wechsler et al. 2016; NAEYC 2020)

Quality improvement and accreditation are meant to be journeys that help programs grow and strengthen over time. They are designed to incorporate reflection, planning, collaboration, and refined practice through implementation (see “Choosing How to Measure Quality” below). In the following sections, I outline specific steps early childhood leaders can take as they embark on guiding their programs through quality improvement efforts. These strategies are based on my experiences supporting both small early childhood programs (two classrooms, seven staff members) and medium-size ones (nine classrooms, 40 staff).

Choosing How to Measure Quality

Different options are available to early learning programs seeking quality improvement. These include accreditation (such as NAEYC’s), a state’s Quality Improvement System (QIS) or Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS), or assessments of learning and/or teaching environments. Each has its own requirements.

NAEYC accreditation, for example, entails site visits and the creation of rigorous documentation (see “Navigating Quality: One Public School System’s Approach to NAEYC Reaccreditation,” by Lori Blake and Monique Wilson Gibbs). QIS and QRIS requirements vary from state to state, but all include program standards and supports; financial incentives such as quality grants, refundable tax credits, and increased Child Care Development Fund subsidy reimbursement rates; quality assurance and monitoring; and consumer education (HHS, n.d.). Additionally, programs can tap research-validated tools to assess their learning environments and the quality of educators’ interactions with children. Examples include environmental rating scales for infant and toddler settings (ITERS) and for preschoolers (ECERS) and the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS).

Taking time to become familiar with these different criteria and tools can help programs identify existing areas of strength and opportunities for growth as they guide leaders in creating a plan for success.

Establish Why Quality Is Important

It is reasonable for educators to feel proud of the work they do. Embarking on quality improvement efforts may make them feel like they have to prove their worth, update their practices, and/or seek validation from an outside source. They may not be aware that families often look for databases of accredited or quality-rated programs when searching for settings for their children. Additionally, they may not know that funding often requires or is based on a program’s accreditation or quality rating. For example, in many states, the formulas for distributing COVID-19 pandemic relief funds were based on factors like enrollment capacity, state quality ratings, and inclusion of children with Individualized Education Programs. Taking time to help staff understand the value of these benefits can validate the pride they already have in their work. It can also support staff buy-in and minimize resistance or frustration.

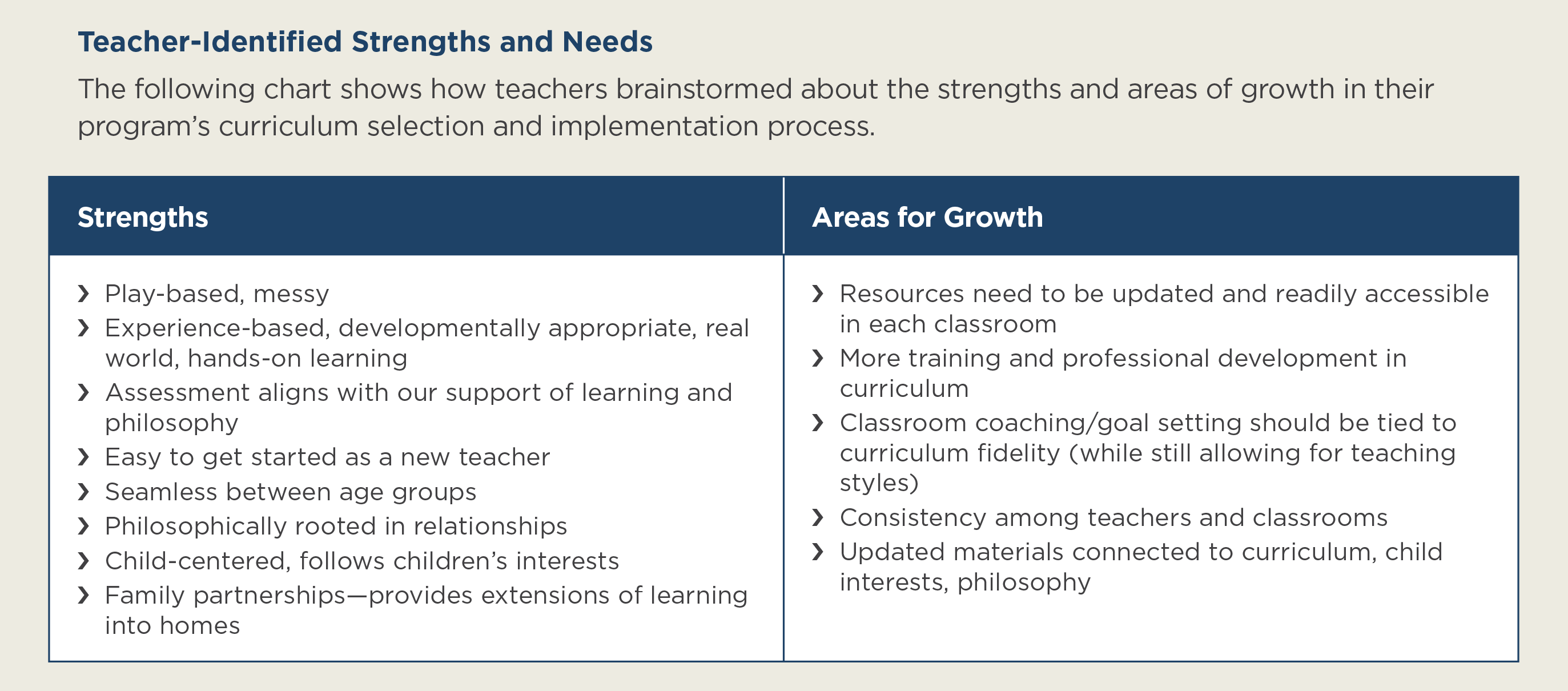

By acknowledging and celebrating existing strengths, educators begin to understand that any areas targeted for improvement are directly connected to existing values and identified growth areas (Douglass, Kirby, & Malone 2023). For example, in one program I led, I asked staff members to brainstorm and list the program’s strengths, needs, and the impact a quality improvement process could have. One area of growth these educators identified was curriculum selection and implementation (see “Teacher-Identified Strengths and Needs” below). Our brainstorming helped staff see how exploring new curricula could meet their self-identified areas for growth. It also helped me ensure that we maintained current strengths while working toward the goal of a high-quality rating and NAEYC accreditation.

In addition to brainstorming, we explored the differences between required rules and regulations (teacher-child ratios, fire safety protocols, sleep practices) and those recommended for quality implementation, validation, and advisory or supplementary guidance (family engagement, staff professional development, and environmental quality). For most staff, this exploration motivated them to engage in more than just basic required practices. However, some staff needed support to understand the added value of quality recommendations. Building this awareness included a lot of visioning about what we wanted for children. We engaged in learning sessions and book studies to unpack our philosophy and to visualize what quality measures would look like in practice. Establishing the importance of quality is an ongoing cycle of reflection: Are current practices reflective of a program’s values, or is there room for improvement?

Involve Staff

The quality improvement process is a team effort. While led by a program administrator or leader, many others can contribute meaningfully to the process. As Douglass noted, “For too long now, early childhood educators have been seen as an object of change rather than the architects and co-creators of change” (2017, 5). People are more likely to participate in and embrace change when it feels like it is happening with them instead of to them.

When the program I led began seeking NAEYC accreditation, we established several committees to engage staff. These included

- a NAEYC accreditation committee, which facilitated the accreditation process. Staff focused on understanding the process, coordinating resources, anticipating a timeline, and finding answers to initial questions.

- an assessment committee, whose members explored and selected a child assessment tool informed by requirements from state quality systems and NAEYC accreditation. This included reviewing state-approved options and determining what would fit best with our philosophy.

- a curriculum committee, which was designed to explore and select new curricula. Similar to the process we followed to choose a child assessment tool, this committee reviewed state-approved curricula and chose one that most closely aligned with our existing philosophy and learning facilitation.

- a diversity committee, which was tasked with improving anti-bias education and diversity, equity, and inclusion practices during the quality improvement process.

Staff had the autonomy to join one, many, or none of these groups. This was a great time to optimize the strengths and interests of our team. Those who participated were able to take on leadership roles outside of the classroom; as the process advanced, representatives from each class began to take the lead on certain accreditation elements, such as creating classroom portfolios.

When staff members are included in decision-making processes, they are more motivated and engaged (Douglass, Kirby, & Malone 2023). This is especially true as early childhood education programs begin the quality improvement process. Classroom teachers may not be familiar with long-term, comprehensive improvement plans. Giving them access to the implementation plan as well as tools and resources can build perspectives and reduce how abstract the process may feel. Consider creating a dashboard, sharable files, or other accessible tools, so staff can see progress. In our program, we used shared Google files to ensure everyone had access to the same information.

Address Conflict

Going through the quality improvement process can be stressful and overwhelming at times—for both leaders and staff. This may result in tension if staff members believe that work is unfairly distributed, information is not well-communicated, deadlines are missed, or other responsibilities are taking a backseat to quality improvement tasks.

It is important for leaders to address tensions as they arise and use them as opportunities to develop and hone communication and problem-solving skills. While it may feel time consuming, engaging in productive conflict resolution can produce many benefits, including improved outcomes, better relationships, and increased job satisfaction (Gallo 2017). For example, our curriculum committee was tasked with reviewing state-approved assessment and curricula and choosing one for the center to implement. During this process, people sometimes had strong feelings about overall change or the tool that was selected. Slowing down and taking time to allow them to express their feelings and talk through any uncertainties reduced stress and built empathy among staff to support each other through the process.

Engage External Stakeholders

While a program’s staff may spend the most time engaging in quality improvement activities, it is equally important for leaders to connect with families and other stakeholders, such as volunteers, board members, or investors. This can be done by

- surveying families to gauge how they have experienced program practices. This may include asking for feedback regarding family engagement opportunities, interactions and communication with staff and administration, and access to information and resources. Programs can survey families in a number of ways to ensure maximum participation: Paper surveys can be distributed at pickup or drop-off times; families can be surveyed using a web-based or other technology platform; and listening sessions (both virtual and in-person) can be scheduled. Resources and opportunities should be provided in the primary languages staff and families speak.

- seeking input from practitioners who applied to work in the program but declined employment offers. What barriers did they face?

- asking families who are not enrolled in the program—those either on the waitlist or who declined to enroll—about their needs and perspectives.

- inviting community members (agencies, nearby businesses) to give input on the program’s presence in, impact on, and relationship with the community.

While it may take time to gather all of this information, the effort can provide insights that extend beyond daily interactions and observations. We used data from our family surveys to inform changes in operating hours, adjust our menus and meal offerings, and assess the frequency and format of communicating developmental information to families. Knowing families’ communication preferences was especially helpful when we were choosing a child assessment tool that would exist on a family engagement platform.

Make Time to Check In

Educating and caring for children while also navigating change can be daunting. As such, it is crucial for program leaders to build in time for staff to share how they are feeling. This may include scheduling meetings with individual teachers, teaching teams, and/or the entire staff. Leaders might want to host mixed-group listening sessions to allow people in different roles to hear each other’s perspectives. Gathering ideas and feedback via digital tools (video chat sessions, surveys, anonymous digital suggestion boxes) is also helpful. For example, during implementation of a new child assessment tool, we created drop-in office hours for staff to come and talk about any challenges they were facing. This approach helped us meet their individual needs but also informed our adjustments to timelines and processes.

Frequent opportunities for discussion and feedback can result in new solutions and ideas (Douglass 2017). When leaders open themselves to gathering staff members’ perspectives, they learn how to support them more effectively. They may also gain new ideas: When we were trying to come up with engaging ways to become familiar with NAEYC’s accreditation standards, one of our lead teachers suggested a “focus of the week” model so that staff could familiarize themselves with the standards over time. Asking for—and listening to—feedback ensured teachers’ commitment to and participation in the quality improvement journey.

Celebrate Progress

The path toward continuous quality and improvement is made up of small steps. As you work through this process, it is worth celebrating the advances made and the goals that are met along the way. We periodically reviewed “small wins” (purchasing new materials or books that better represented the diversity of children and families we served) and “big wins” (purchasing tablets for each classroom to use the child assessment tool and family engagement app).

While we acknowledged milestones during a staff meeting, there are other ways of celebrating and honoring progress. Before diving into a season of change, program leaders can survey staff members to find out how they would like to be thanked, supported, or rejuvenated after reaching certain goals. This might include handwritten notes, a snack bar or staff meal, an event for staff and families that highlights successes, or a newsletter or bulletin board that documents and describes the milestones achieved. Such acknowledgments will spark renewed energy for the next step in the quality improvement process and keep stakeholders excited.

Avoid Other Big Changes

Organizational change is more successful if everyone puts energy toward the same goal (Douglass 2017). If too many changes occur at once, staff can feel confused, overwhelmed, or disengaged. For that reason, it is best to avoid making other program-wide changes that are unrelated to a quality improvement plan.

For example, COVID-19 occurred in the middle of our quality improvement and accreditation process when I led the University of Michigan Health System Children’s Center. This meant we had to slow things down, identify our priorities, and focus on managing pandemic-related stresses and procedures. Besides helping teachers to avoid feeling overwhelmed, this shift underscored that the process of quality improvement was a group effort. We adjusted our timeline for accreditation, pausing during the initial onset of COVID and then engaging in the self-study process when we felt we had the time and energy. We maintained our state quality improvement process because we had more elements in place. We continued to center both efforts in our decision making, knowing that our long-term goal was to stay on track and in alignment with the highest standards.

You Are Not Alone!

Facing any big change or project can be daunting. However, connecting with others who have experienced the process or are currently going through it can provide insights and motivation. Leaders can connect with local programs by searching their state’s system or NAEYC’s accreditation database. They can also tap social media or public forums like NAEYC’s HELLO! platform to find other programs seeking quality improvement. These can be great sources for gathering information and expertise and for processing any feelings of stress or confusion.

Engaging in quality improvement is a rewarding process. By approaching it with intention, reflection, and commitment, leaders help ensure that everyone in their early childhood programs—including children, families, and stakeholders—gets the most out of the process.

Photograph: © Getty Images

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Douglass, A.L. 2017. Leading for Change in Early Childhood Programs: Cultivating Leadership from Within. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Douglass, A.L., G. Kirby, & L. Malone. 2023. Theory of Change of Early Care and Education Leadership for Quality Improvement. OPRE Report #2023-097. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/theory-change-early-care-and-education-leadership-quality-improvement.

Gallo, A. 2017. Harvard Business Review Guide to Dealing with Conflict. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Goffin, S.G., R.E. Allvin, D. Flis, & A. Wat. 2015. “Advancing Early Childhood Education as a Professional Field of Practice.” Child Care Aware of America.

info.childcareaware.org/blog/fulfilling-the-promise-of-early-childhood-education-advancing-early-childhood-education-as-a-professional-field-of-practice.

Great Start to Quality. n.d. “High Quality Care Builds a Foundation for Success.” Accessed April 13, 2024. greatstarttoquality.org/why-high-quality-matters.

HHS (US Department of Health and Human Services). n.d. “QRIS Resource Guide.” Accessed July 22, 2024. ecquality.acf.hhs.gov/about-qris.

Jancart, K., J. Vecchiarelli, A.M. Paolicelli, & K. McGoey. 2021. Long-Term Outcomes of Early Childhood Programs: Evidence on Head Start, Perry Preschool Program, and Abecedarian. Research summary. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

NAEYC. 2022. NAEYC Early Learning Program Accreditation Standards and Assessment Items. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/user-126377/2022elpstandardsandassessmentitems-compressed_2.pdf.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

NCECQA (National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance). n.d. QRIS Resource Guide. Accessed April 13, 2024. ecquality.acf.hhs.gov.

Schoch, A.D., C.S. Gerson, T. Halle, & M. Bredeson. 2023. Children’s Learning and Development Benefits from High-Quality Early Care and Education: A Summary of the Evidence. OPRE Report #2023-226. Washington, DC: Administration for Children and Families. acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/%232023-226%20Benefits%20from%20ECE%20Highlight%20508.pdf.

Wechsler, W., H. Melnick, A. Maier, & J. Bishop. 2016. The Building Blocks of High-Quality Early Childhood Education Programs. Palo Alto, CA: The Learning Policy Institute. files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606352.pdf.

Christine Snyder, MA, has worked in the education field since 1999 as a teacher, administrator, professor, author, and trainer/coach. She is pursuing a PhD in educational studies. Christine is currently director of child and family care at the University of Michigan, a lecturer at Eastern Michigan University, and an independent early childhood consultant.