The Healing Power of Children’s Books for Children Experiencing Loss

You are here

Alex, a 5-year-old boy in the inclusive classroom where I teach, was absent from school on the first anniversary of his dad’s death. In the month he had been in my classroom, Alex hadn’t mentioned his dad once, and he avoided or left conversations about families. When he returned to school the next day, I chose to read The Invisible String, by Patrice Karst, for our whole-group read aloud. I hoped that the story would provide Alex with an example he could relate to and that it would also help children who felt sad, anxious, or upset about being away from home caregivers while at school. The story introduces the idea of an “invisible string” that keeps loved ones connected to each other no matter the situation or circumstance (even if, for example, one of them is deep underwater or in space, or they have an argument or do something wrong). One spread features a child asking if the string can reach his uncle in heaven. From conversations with Alex’s family, I knew that heaven was the term they used to describe where his dad was now. As I read aloud, Alex sat still and silent, staring at this spread.

During playtime later that day, Alex approached me, saying, “Ms. Emily, my dad is in heaven.” When I told him I also had a family member who had died, he looked stunned: “You have someone in heaven too? I thought it was just me.” The Invisible String offered Alex a way to connect his experiences to those of others. He brought up his dad multiple times after that, even discussing him with other children with a comfort and level of understanding I hadn’t expected. This underscores the crucial role that children’s books can play in fostering connections and understanding among children.

Conversations similar to the one I had with Alex happen often in my setting. I am an early childhood special education teacher in an inclusive setting in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Our school district is located just south of the city center. It has a small-town feel while also including a large military community near the Air Force Academy and Fort Carson Army Base. In our district, 46 percent of families qualify for free or reduced lunch programs, and many children have family members who serve in the military. Our district’s public preschool program is free for families in the community. An educational assistant and I teach morning and afternoon classes, with 16 children in each class. Half of the children have Individualized Education Programs and receive special education services within the classroom setting. The other half are children without disabilities who live in the community, though priority for these class placements is based on factors identified by our district/state, such as children from low-income or single-parent households, those in foster care, or emergent multilingual learners. My dad served in the Air Force, and I have developed an understanding of neurodiversity due to being diagnosed with a rare sleep disorder. Through my own experiences, I’ve seen how many of us need responsive and individualized practices for various reasons throughout our lives, and I can relate to many in my school community.

Working with the children in my setting, I’ve found that the transformative power of literature in education is undeniable. Books are my favorite resource for fostering connections and helping children make meaning of the diverse world around them. They are an important part of our inclusive environment and activities, and we integrate books about different aspects of diversity and inclusion. For example, we have books that mention different cultures and religions as part of a diverse world. As another example, when Ellie asked, “Why doesn’t Ryan talk?” we read The Girl Who Thought in Pictures: The Story of Dr. Temple Grandin, by Julia Finley Mosca, and discussed different communication methods. Books can also help children understand their own experiences, including loss. Dealing with loss is challenging, painful, and difficult. For a young child still developing an understanding of connection and relationships, talking about the death or absence of a family member is an important part of helping them process the situation.

Noah, a 4-year-old boy, experienced loss when his parents separated and his mom moved away. While he occasionally saw his mom, he struggled with the change in routine, missed her, and felt confusion about her absence. For Noah, the children’s book The Garden of Hope, by Isabel Otter, was a valuable resource to read with him individually. I appreciate this book’s broad context. It begins, “Things had changed since Mum had been gone,” without offering specific details about why Mum is absent. Readers can connect the story to their own individual experiences. Rather than focusing solely on Mum’s absence, the story explores how Maya and Dad move forward, struggle, and adapt to their new life. “Did the mom go to the hotel?” Noah asked. “My mom went to the hotel.” This was the first time Noah mentioned that his mom had left, despite my awareness of his family’s changes and my observations of changes in his behavior at school.

Over the following weeks, Noah continued to demonstrate connection-seeking behaviors, which often manifested as disruptive or aggressive, such as hitting me or his peers, yelling, and refusing to participate. After a particularly challenging week for Noah, I asked if he wanted to sit with me in my rocking chair. As a special education teacher, I have found that rocking chairs provide wonderful sensory input for many children. For Noah, this time offered an opportunity to connect. Sitting on my lap, he leaned his head against my shoulder.

“I noticed you’ve had a lot of feelings this week and seem to be having a hard time,” I began.

He simply nodded against my shoulder.

“I’m sorry to see you struggling. Did something happen?”

Cuddled on my lap, he responded, “My mom went back to the hotel again. I want to see my mom.”

For the next five minutes, we rocked back and forth, talking about him and his mom, what he enjoyed doing with her, and his hope to call her that night.

When I asked about his dad, his whispered response came with his head still on my shoulder.

“Dad said I’m being bad. I’m worried he won’t like me anymore.”

“Noah, you are amazing. Sometimes we all make hurtful choices, but you are still good. I love you, your teachers love you, your friends love you, your dad loves you, and your mom loves you, even when she’s not there. I’m so glad you’re part of our school family.”

He was silent, continuing to rock on my lap for a few minutes before wiping his eyes and saying he was ready to play. Over the next weeks and months, this process repeated as Noah made significant progress in self-regulation and emotional processing skills. About a month after our first rocking chair time, when Noah grew frustrated with a peer situation on the playground, I watched him take a deep breath and walk over to me instead of reacting physically.

“Ms. Emily, can you rock me in the chair when we get back to class?”

Our rocking chair times became less about regulation and more about enjoyable conversations and reading books together that he chose, connecting over those shared reading experiences for fun and comfort.

We all have unique experiences, and resources for teachers, families, and children constantly evolve. For example, I recently purchased Where Do They Go?, by Julia Alvarez. This book explicitly asks, “When somebody dies, where do they go?” and explores different ideas about an afterlife. These range from connecting with nature (“Do they turn into clouds and change every hour: a flamingo, a cat, a dancer, a flower?”) to staying close to a loved one (“Is it them that I feel, alive in my heart?”). While I haven’t yet used this book, it’s there for me to consider and use for specific reasons. And while no families raised concerns about the books I have shared, I know that, in general, resources surrounding loss vary—from books that center on vague connections to nature to those written for specific religious or cultural contexts. Where Do They Go? is a resource I can return to in the future, especially when supporting a child who is curious about the death of a loved one, a child who may be fearful of death, or a family unsure of how to talk about death with their child.

While I don’t have all the answers about a topic like death and grief, as a teacher, it’s my responsibility to assist children in seeking them. Our children spend their formative years in our settings and need support understanding the diverse world and their place in it. Like Alex and Noah, all children need to understand they are not alone in their struggles or experiences of loss. Children’s literature serves as an invaluable tool for fostering understanding, connection, and meaning making around challenging life experiences like loss. Teachers can continuously explore diverse book options that authentically represent children’s cultures and circumstances, create safe spaces for dialogue, and leverage the power of storytelling to help children process grief, build resilience, and find comfort in knowing they are not alone.

Further Resources

For more on the topic of navigating loss and grief with children, see these NAEYC resources:

- Life and Death in Nature: Outdoor Discoveries Bring the Topic of Death into a Preschool Classroom,” by Dani Porter Born, in the May 2019 issue of Young Children

- Helping Young Children Grieve and Understand Death, by David J. Schonfeld, in the May 2019 issue of Young Children

- How Early Childhood Educators Can Explain Death to Children, by David J. Schonfeld, in the Spring 2021 issue of Teaching Young Children

- 10X. Inclusive and Nurturing Grief Support for Young Children and Families, by Suzanne J. Bayer, in the Spring 2021 issue of Teaching Young Children

- The Toads: Refocusing the Lens (Voices), by Amanda Jo Messer, in the December 2020 issue of Young Children

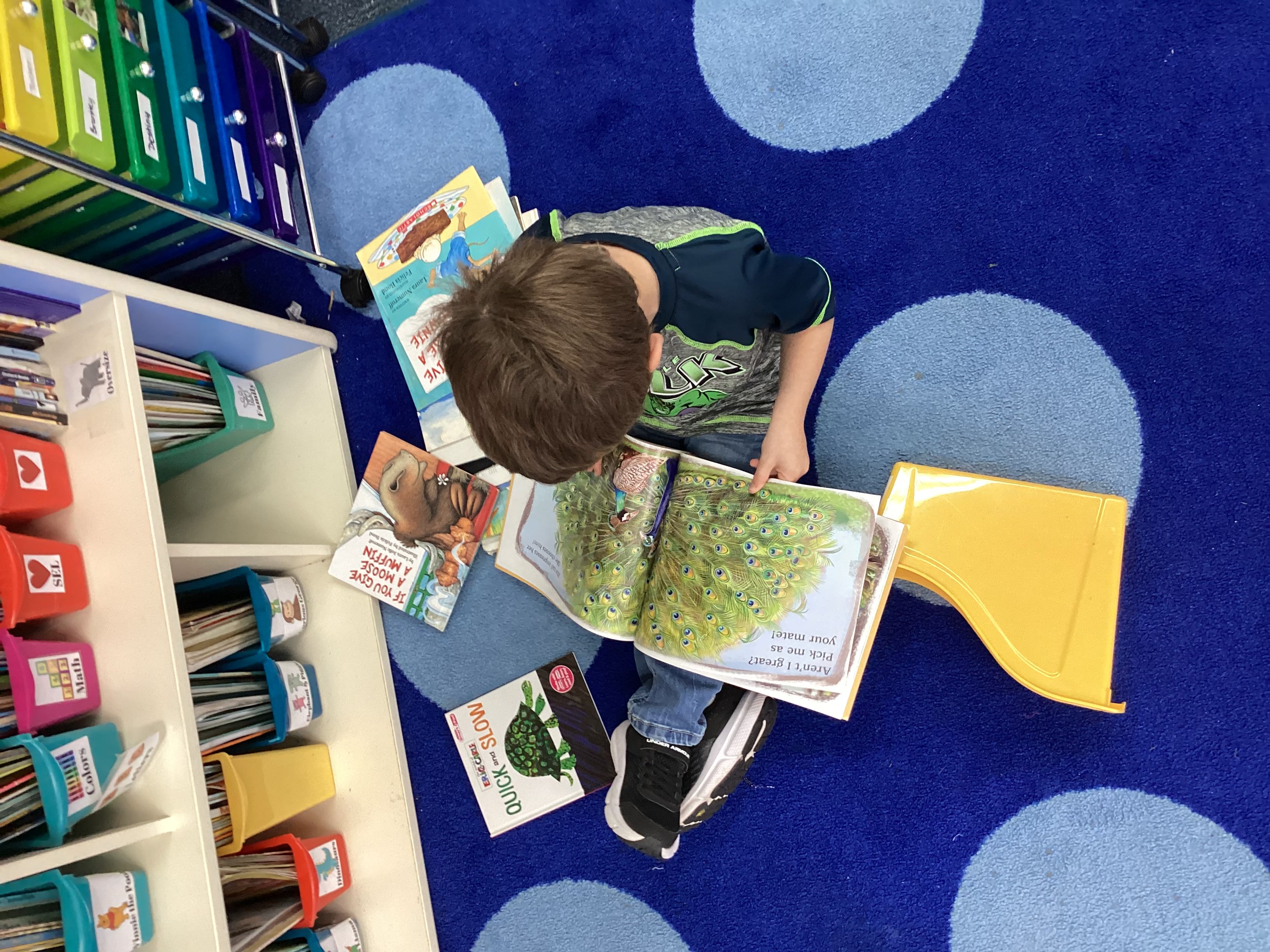

Photographs: Header image © Getty; photos 1 & 2 courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Emily Sturt is an early childhood special educator and inclusive preschool teacher in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Emily has teaching experience in multiple countries and is an alumna of Teach Plus, advocating for education policy for the state of Colorado. [email protected]