14-Day Salad: Using Project-Based Learning to Grow Microgreens

You are here

In project-based learning, spontaneous conversations during lunch can lead to interesting learning experiences. We discovered that it is possible to grow a salad indoors, in the middle of winter, in under a month!

The sprouting of an idea

Over the winter, I was sitting with a group of pre-K children on a particularly cold and snowy day. They were eating a cafeteria-prepared lunch of pizza and salad. Amid the many conversations, one child asked, “Mrs. Barresi, can we grow a salad?”

I was not surprised by this question—there’s almost always something growing in our classroom. “That’s an interesting question,” I replied. Another child chimed in, “Not now, not in the snow!” A long conversation followed about plants and what they need in order to grow.

It’s true: vegetables won’t typically grow outside in the middle of winter, and especially not outside in Connecticut, where our preschool is! And even if we planted a garden in the spring, when the sun warms the soil, who would tend to it during the long, hot summer? Would it still be alive when we returned to school in the fall? As a Reggio Emilia-inspired school that embraces project-based learning, we decided to do some research.

After lunch we turned to the Smartboard, opened up Google, and asked, “Can we grow a garden in the winter?” This led us to information about building a cold frame (a box with a clear glass or plastic lid or cover used as a mini greenhouse). Cold frames are used for growing plants outdoors before the weather is warm. While that certainly was a possibility, building a cold frame was a big project. We kept digging.

“It’s warm in here,” said Thomas. “Can we grow a garden in our classroom?” So next we searched, “Can we grow a garden inside?”

That’s when we discovered microgreens! They can be grown indoors, any time of the year, and they don’t require a lot of space. The more we read about microgreens, the greater our excitement became.

What are microgreens?

Microgreens are young seedlings of edible plants (kale, radishes) that are harvested shortly after germination when the stem, seedling leaves, and first set of true leaves have grown. Much like our preschoolers, they are tiny and packed with energy—nutritional energy!

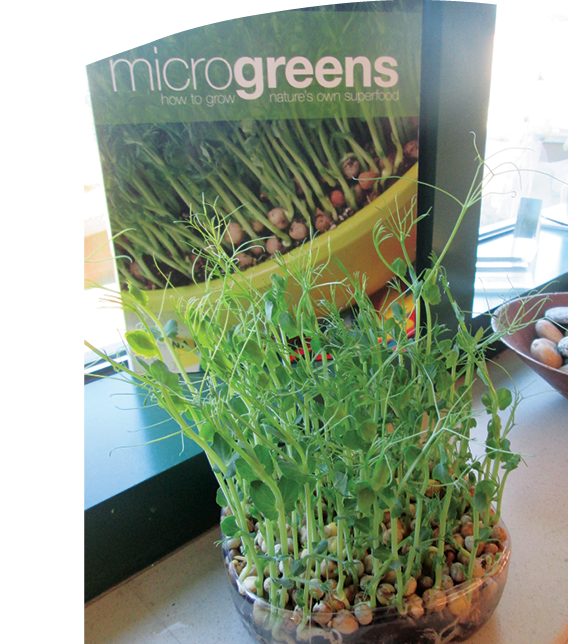

To learn even more about microgreens, we searched the local library catalog. We found the book Microgreens: How to Grow Nature’s Own Superfood, by Fionna Hill. I told the children that I would pick up the book at the library that evening.

In the meantime, we decided to make a K-W-L chart—a chart that helps organize information using three categories: What I KNOW, WONDER, and LEARNED.

The roots of a project

The next day, book in hand, we explored the vibrant pictures. The children looked in the book for answers to questions in the “What I Wonder” column of our K-W-L chart. We learned that we can eat the microgreens of most vegetables, herbs, and spices. Some other facts we learned:

- Unlike spacing seeds and planting rows in a traditional garden, microgreen seeds are planted in a layer sprinkled across the top of the soil.

- Since the plants don’t grow very big, neither does the root system, so the seeds can be planted in shallow containers.

- The first set of leaves are called seedling leaves; these are part of the seed and help to nourish the sprouting seed. Our salad greens could be harvested after the first set of true leaves emerged. True leaves are leaves that grow after the seed has sprouted.

- It usually takes 2 to 4 weeks to grow microgreens.

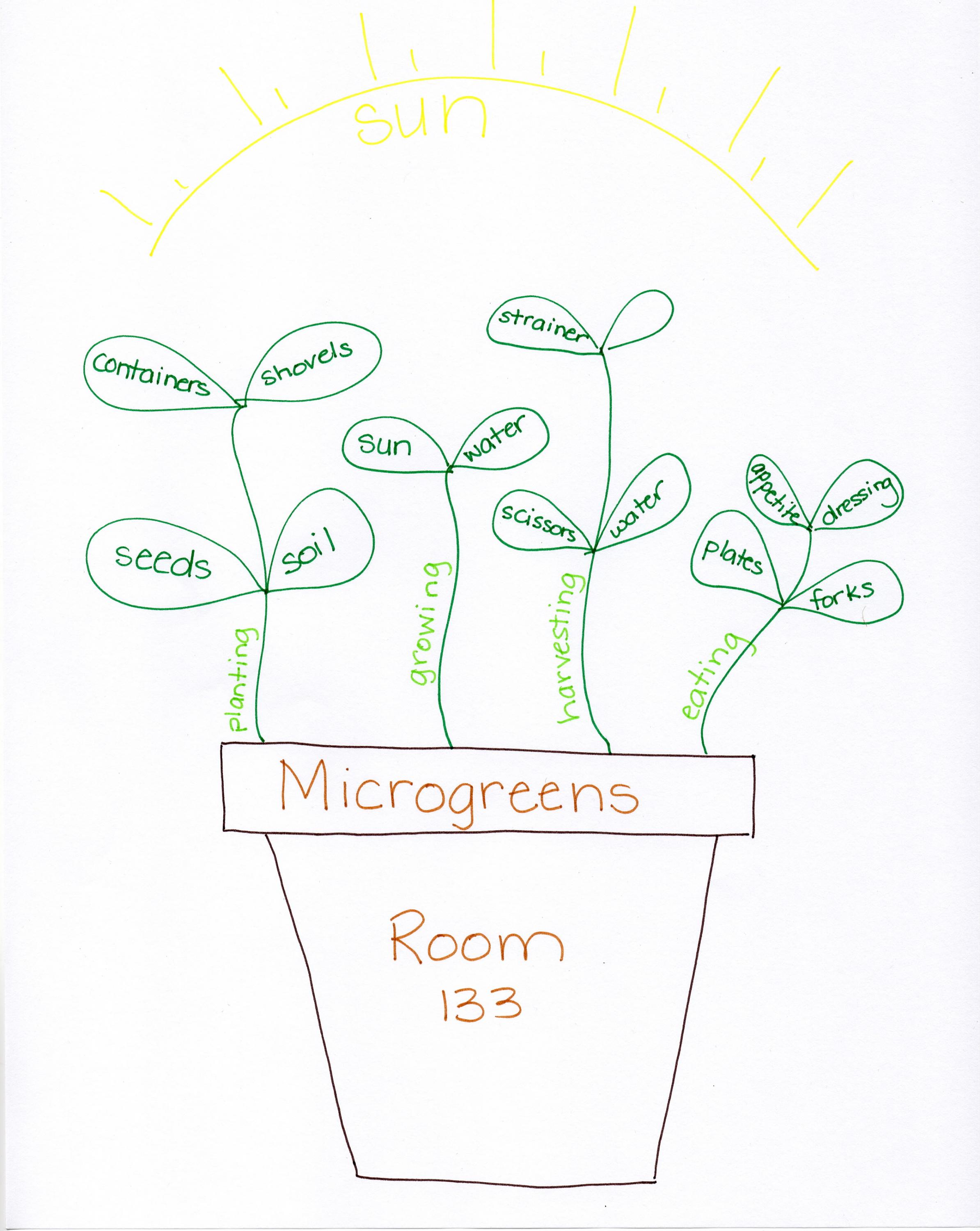

We decided to give microgreens a try. We made a planning web—or in this case, a planning plant—to help us organize our project.

“How are we going to conduct our investigation?” I asked the children.

“We need dirt!” one child answered.

“And something to grow in,” another child said.

“Oh, so we should make a list of supplies we need to plant our garden?” I asked the children.

What I Know

- Plants need dirt

- Plants need water

- Plants need sun

- Plants start with seeds

What I Wonder

What I Wonder

- Where we can get the seeds

- What kind of seeds we should get

- How we plant the seeds

- How big they will grow

- How long it will take

- How our plants will taste

- How we will know when to eat the plants

What I Learned

- We ordered the seeds online

- We ordered seeds of food we like

- Microgreen seeds are planted in a layer, not spread out

- The plants had seedling leaves and one set of true leaves when we harvested them

- The peas grew 3”, the other plants grew 2” tall

- They took two weeks to grow

- They tasted like salad, the peas were sweet

Acquiring seeds and supplies

Next, we needed to locate a source for seeds. Seed packets found in most garden centers contained a very small amount of seeds; purchasing those would have been cost prohibitive for our project. We went to the Smartboard again, typed in “microgreen seeds,” and found several suppliers.

Next, we needed to locate a source for seeds. Seed packets found in most garden centers contained a very small amount of seeds; purchasing those would have been cost prohibitive for our project. We went to the Smartboard again, typed in “microgreen seeds,” and found several suppliers.

There were so many different kinds of seeds to choose from, but we narrowed our selection down to three: carrots, peas, and clover. First we brainstormed a list of vegetables the class liked to eat, then children voted for their top two; carrots and peas were favorites. We chose clover because we were surprised that we could eat it and we wanted to try it. We placed our order and eagerly waited for our seeds to arrive.

While waiting for the seeds, we referred to our planning plant: it was now time to gather our tools and supplies so that we were ready when our seeds arrived. We wondered together where we might get some of the things we needed. One child suggested, “My mom has a garden. Maybe I could ask her.” This, of course, prompted several other children to chime in, “Me too!” We decided to write a letter:

While waiting for the seeds, we referred to our planning plant: it was now time to gather our tools and supplies so that we were ready when our seeds arrived. We wondered together where we might get some of the things we needed. One child suggested, “My mom has a garden. Maybe I could ask her.” This, of course, prompted several other children to chime in, “Me too!” We decided to write a letter:

Sure enough, our parents rose to the challenge and provided us with the supplies we needed to grow our own salad—including some recipes for salad dressing!

Harvesting our idea

We were so excited when our seeds arrived! After opening the packages, we immediately noticed that the pea seeds looked just like peas, while the carrot and clover seeds were very tiny. Following the directions we had read in the book and online, we prepared our microgreen garden. Each child took a turn adding soil to the planters and sprinkling seeds across the surface. Careful not to overwater the plants, we set up a watering station and used mister spray bottles every day. The children documented the growth of our plants in two ways: 1) some chose to take pictures with the iPads and create a photo documentary, while 2) others drew observations in their nature journals.

In two weeks, we were able to harvest our microgreens and enjoy salad with our lunch while we looked out over our snow-covered outdoor learning environment!

Try this with your class!

Here’s what you need to get started:

Sunny window: microgreens need at least four hours of direct sunlight a day.

Sunny window: microgreens need at least four hours of direct sunlight a day.

Shallow dish: seed starting trays or other shallow containers, like shallow food storage containers, recycled Styrofoam take-out containers, recycled rotisserie chicken trays, or a jelly roll pan.

Seeds:

- Salad greens (kale, arugula, mustard, sorrel)

- Leafy vegetables (radishes, beets, carrots, peas)

- Herbs (cilantro, basil, chervil, parsley)

- Edible flowers (zucchini blossoms, violets, rose petals)

Potting soil: seed-starting medium (made up of ingredients other than soil—things like milled sphagnum moss, peat, vermiculite, or perlite) or potting soil; avoid soils with fertilizers mixed in because they include chemicals that aren’t good for children to eat.

Spray bottle/mister: small bottles for little hands that mist instead of soak.

STANDARD 2: CURRICULUM

G: Science

H: Technology

K: Health and Safety

S.60.8: Demonstrate an understanding of how living things grow and change through predictable stages (e.g., birth, growth, reproduction, death)

S.60.2: Engage in collaborative investigations to describe phenomena or to explore cause and effect relationships

Photographs: © Getty Images and courtesy of the author

Jean Barresi taught preschool for over 30 years before “graduating” to kindergarten. She teaches at Riverside Magnet School at Goodwin College, in East Hartford, Connecticut.