“The Sky Is Orange!” Reflecting on an Investigation of Light and Shadows

You are here

During the 2020 California wildfires, the sky above Transbay Child Development Center in San Francisco turned orange. It was dark during the day as visibility was reduced. Several of the children in our center were afraid to come to school and were reluctant to participate in outdoor play. They didn’t know what to expect. Others asked repeatedly, “Why is the sky orange?”

During the 2020 California wildfires, the sky above Transbay Child Development Center in San Francisco turned orange. It was dark during the day as visibility was reduced. Several of the children in our center were afraid to come to school and were reluctant to participate in outdoor play. They didn’t know what to expect. Others asked repeatedly, “Why is the sky orange?”

Rather than offering reassurances or explanations, we used their reactions to the absence of natural light as a provocation for a tinkering investigation into light and shadows. We offered them different light sources and materials, so they could begin investigating how light as a material can be blocked, bent, and bounced.

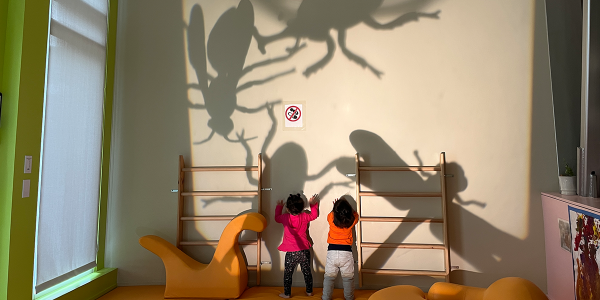

Transbay serves children 18 months to 6 years old. That’s a wide range of ages and skills, so we had to consider different materials, learning goals, and levels of choice and support that were responsive to each learner. For example, toddlers love movement. To integrate this with an exploration of light, we shined a light projector on a blank wall in the area we use for tinkering. During their play, they unintentionally blocked the light and cast shadows on the wall as they moved back and forth in front of the projector. As they began making connections between their movements and the changes in light and shadows, they started doing this intentionally. Our 4- and 5-year-olds explored a variety of materials to produce quality shadows and to investigate how the color and thickness of materials affect light. Because family participation supports children on their journey of tinkering, we invited families to send us pictures of shadows they discovered at home.

Choice and the environment are so important in tinkering explorations. There is intentional structure—we don’t use materials that aren’t safe; children are taught to respect each other’s space—but there’s flexibility within that structure. Children must have the right to choose the materials they need and the freedom to create and problem solve. Some educators consider the environment the child’s third teacher, and I agree. It must be a stimulating, flexible space, and it must be organized. For our light and shadows exploration, we kept all the materials that block light in one area. We put materials that light can pass through in another area. Sources of light (flashlights, block lights, different colored lights) were in a third. This intentionality supported children in making connections and constructing knowledge about the properties of light regardless of a material’s texture, size, weight, or shape. For example, a piece of fruit and a piece of cardboard will both cast solid shadows even though one is edible and spherical and the other is not.

Tinkering lasts as long as children are interested. In our setting, the children dictate the pace and the length of a project with the educator as a facilitator. It’s important to remember that interest is different from excitement. Excitement fizzles out: a child sees a plane, shouts, “Yay! A plane!”, then goes on to another activity once the plane flies away. Interest is quiet and slow and needs time and space. Because it requires hard work, concentration, and repeated failures, it evokes a range of feelings that may not always be positive. You can see the mental wheels turning. This is curiosity-driven play, and you know an exploration is succeeding the moment children start asking themselves, “I wonder what will happen if . . . .” This shows they are deliberately owning their own actions as part of the exploratory process.

The tinkering cycle begins with planning and reflecting on an idea you want to launch. Reflection is important throughout the exploration: Are children meeting the goals you set? Are they having meaningful conversations? Are they able to articulate new knowledge? The answers to these questions may lead you to relaunching an idea, so your investigation can go deeper. During our light and shadows investigation, something that confused our older children was where shadows would be cast. At the beginning of the study, they drew pictures of shadows, but the shadows weren’t aligned with a light source. Reflecting on their drawings, we decided to relaunch the project, specifically asking: “Where is the light source located?”; “Where is your shadow?” After these more detailed explorations, the pictures they drew had the shadows in the right places. The children really understood what was happening and exhibited this by making their thinking visible in their drawings.

This speaks to the idea of failure while tinkering. When the questions start, failure is simply part of the process. The children are investigating and making “intelligent” failures: for the scientist, failing is just one more way of knowing how not to do something. During a STEM exploration, educators need to ask themselves, “How do I support children to overcome their frustrations and discover the ‘aha’ moment that is around the corner?”

If you haven’t tried tinkering with the children in your setting, you should. It’s so fulfilling. It’s really joyful. It stretches children as well as educators, as it requires adaptability, flexibility, creativity, and problem-solving skills, to name a few. There is a wide range of skills children can develop by engaging in tinkering that will stretch throughout the learning day.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 2: Curriculum

2G: Science

2H: Technology

Ihuoma Iheukwumere is the site manager of Transbay Child Development Center in San Francisco, California.