"What About People Like Me?" Teaching Preschoolers about Segregation and "Peace Heroes"

You are here

As part of the anti-bias curriculum at the preschool where I teach, we study the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. throughout the year. Learning about Dr. King’s life provides us with a wonderful opportunity to reflect on the principles he stood for. These are ideas my colleagues and I believe are very appropriate for preschoolers to explore and revisit often.

We focus on Dr. King’s desire for all people to be treated fairly regardless of the color of their skin. Solving problems with words; being fair, kind, and inclusive; appreciating similarities and differences among people—these are all ideas we include during morning meetings, small group activities, read alouds, and regular conversations.

In October of 2018, I began by reading a book to the 4- and 5-year-olds in my classroom that was written by a former teacher at our school. Titled Martin Luther King, Jr. and You, the book begins by describing Dr. King and his family, his work as a pastor, and his role in the community. One page introduces his work with Rosa Parks and states that the bus company had an unfair rule: “Their rule was that only some people could sit at the front of the bus.” The next page then shares how the community boycotted the bus company. The book does not explain segregation.

When I read this part of the book, I noticed that many of the children looked confused. I paused the read aloud and asked them to share their questions. Elena asked, “Who could sit at the front?” Then Jane wondered, “Why couldn’t Rosa Parks sit at the front of the bus?”

I wasn’t sure how to respond. I thought to myself, “Is it age appropriate to introduce them to segregation? How would I explain it?” I decided to respond by telling the children, “Our country has had a lot of unfair rules based on the color of people’s skin. There used to be a bus rule that said only White people could sit in the front. Black people had to sit in the back. Rosa Parks was a Black woman and she had to sit in the back.”

Many of the children looked shocked. Several shouted out, “That’s not fair!” and “That’s not okay!” One child put her hands over her ears and said, “This is scary. I don’t want to hear about it.”

Marie, a White child, then announced, “Oh, phew! That wouldn’t happen to me. I’m White!” Before I had time to think about how to reply to this statement, Elena, a multiracial child, exclaimed, “What about people like me? Like Sofia? That is not fair! We are your friends!”

I first responded by agreeing with the children that this was not a fair rule. I reminded them that the rule changed because Rosa Parks worked closely with Dr. King and their community to make it better. “They worked together, just like we do in our classroom community,” I told them. “If something unfair happens to someone in our community, it is all of our responsibility to help make change. People of all skin colors work together to make things fair.” Marie really listened. She then added, “I want to help my friends! I want to help change unfair rules!”

Reflections, questions, and a passion for developing leaders

As I reflected on our conversation later that day, I felt unsure about what I said and the role I should have played in this discussion. Had I given the children too little information? Too much?

Marie’s remark, “Oh, phew! That wouldn’t happen to me. I’m White!” really stood out. It reminded me that educators have lots of work to do in helping young children (and many adults) see that just because something may not directly affect us, that does not mean we should not care or should not do something about it.

I also thought about Elena’s response. She immediately shared her thoughts, standing up for herself and others as a leader. She helped Marie think about what she was saying and prompted the whole class to understand that working to increase fairness is about all of us and is everyone’s responsibility. As her teacher, it was wonderful for me to see her confident self- identity. In a moment in which I hesitated, she was willing to take a risk to speak up about unfairness. She was showing her competence—and she answered my inner question showing that, yes, these are topics children can handle.

I also thought about Elena’s response. She immediately shared her thoughts, standing up for herself and others as a leader. She helped Marie think about what she was saying and prompted the whole class to understand that working to increase fairness is about all of us and is everyone’s responsibility. As her teacher, it was wonderful for me to see her confident self- identity. In a moment in which I hesitated, she was willing to take a risk to speak up about unfairness. She was showing her competence—and she answered my inner question showing that, yes, these are topics children can handle.

Using the Thinking Lens (which you can learn more about in my last TYC article) to reflect further on my role with the children, families, and colleagues, I thought about the following:

What is my role as the children’s teacher?

I would like to learn alongside the children as well as be a leader in helping to guide their critical thinking and problem solving around social justice issues. I want them to be well prepared for their future history and civics classes and, as an essential part of that preparation, I want them to develop their power to make the world better.

What do children want to know? What do children already know and understand?

Children have questions about what is happening in the world today and about history. I planned to observe, listen, and think deeper with the children about these questions.

What is developmentally appropriate and socially and emotionally appropriate for young children?

As I listened to the children’s questions, I thought about the best way to answer. How much should children know about past and present injustices? How much background knowledge did I need to provide for them to think meaningfully about social justice issues? Was I telling them enough? Was I going too far? I planned to do research and collaborate with my colleagues and the children’s families to agree on what is appropriate for the different age groups.

How can I help children feel safe with all the scary things going on in our world?

Often children come to school and share knowledge they have learned at home about our current political climate or about violence in their communities or other places. What is my role when these conversations emerge? How can I help them develop their sense of safety?

How can I introduce powerful “Peace Heroes” in a positive way?

An important part of my anti-bias teaching is exposing children to a diverse group of leaders we call Peace Heroes from history and from today. I purposefully select Peace Heroes from around the world, such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malala Yousafzai, and Mahatma Gandhi, and also from our community, such as Harvey Milk (California’s first openly gay elected official). I know I have to provide context to explain these leaders’ accomplishments, but should I include information about the violence that was often a part of these people’s stories? If yes, how might I do that?

Asking big questions and developing powerful knowledge

After our initial conversation about segregation, we embarked on a seven-month journey learning about important Peace Heroes in our world and what our role could be in making this world a better place. Several weeks in, I realized that our investigation was about so much more. The children had big questions. They wanted to have real conversations and understand why things happen in our world. They asked about life, death, fairness, skin color, and race.

Recently, I was asked by a colleague, “What’s your favorite thing about your work with young children?” I answered, “The spontaneous conversations we have about how the world works.” As I continue my journey as an anti-bias educator, I think often about what is hard and what is rewarding about this work. Although I love engaging in real conversations with the young children in my classroom, it is challenging. I don’t know when these conversations will arise or what children will say or ask. My hope is that I can be as prepared as possible and answer children in a way that is honest, is developmentally appropriate, respects their competence and point of view, helps them feel safe, and shows them their power to change the world.

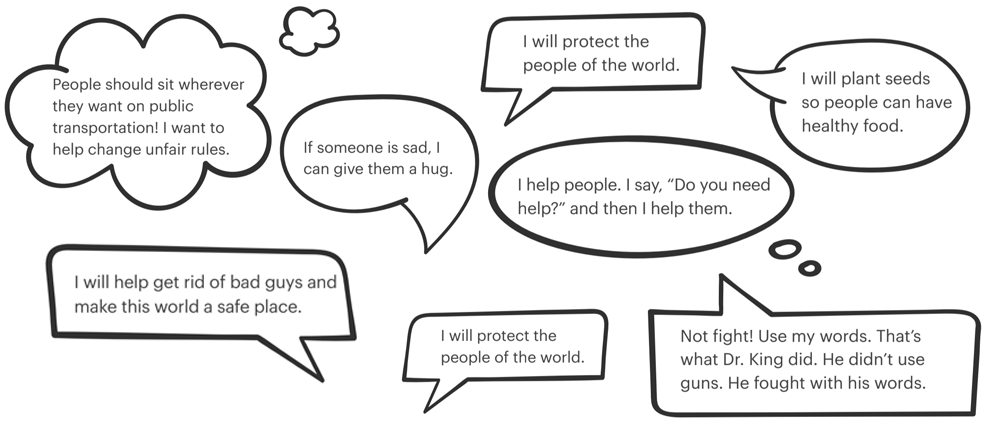

The rest of the school year, the children, my colleagues, and I thought together about what our roles are and what we can do as Peace Heroes in our communities to make this world a better place. We often sang the song “What Can One Little Person Do?,” by Sally Rogers (it’s available for free and includes several Peace Heroes for the children to learn about).

The children answered that question, What can one little person do?, with many ideas that give me hope for the future:

STANDARDS 2: CURRICULUM; 3: TEACHING; 6:STAFF COMPETENCIES, PREPARATION, AND SUPPORT

2L: Social Studies

3B: Creating Caring Communities for Learning

6B: Professional Identity and Recognition

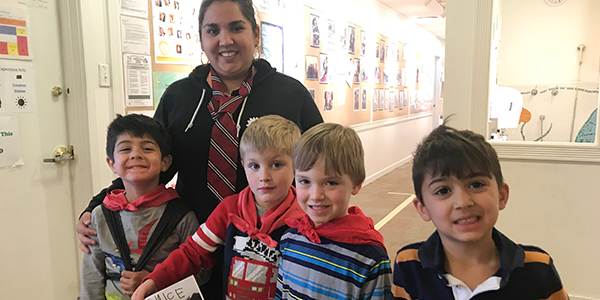

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Nadia Jaboneta is pedagogical leader at Pacific Primary preschool in San Francisco, California. She has 25 years of experience in early childhood education. She has written articles and a book focused on anti-bias education practices, You Can’t Celebrate That! Navigating the Deep Waters of Social Justice Teaching.