Now Read This! Books that Promote Race, Identity, Agency, and Voice

You are here

Editors’ Note: This is the first article in a two-part series that explores promoting children’s identity, agency, and voice regarding race through picture books. Included in this article are three exemplary books that early childhood educators can use to foster critical conversations and to address children’s developing and unknown biases.

It’s the first day of preschool. The class is getting ready for their morning meeting, and Niles, a 4-year-old Black boy, and Rachel, a 4-year-old White girl, sit next to each other on the carpet after playing together in the dramatic play area. Mr. Hawkins (a White male and first-year teacher) rings a chime to get the children’s attention and announces, “Boys and girls, the letter of the day is B. It makes the sound buh, and it’s the first letter in boy, bat, baseball, bright, balloon, and ball.” Without raising his hand, Niles blurts out, “And, and BLACK!” Upon hearing Niles’s outburst, the other children begin laughing. Arie says, “Black, yuck!” and Noah comments, “I hate that color.” Olivia says, “Eww, you’re Black, Niles!” Cody (a 4-year-old White boy) then shouts, “My Dad said Black people get shot a lot!”

Feeling embarrassed and sad by these reactions, Niles pushes back from the group and puts his head in his lap. With a look of shock on his face, Mr. Hawkins immediately says to the class, “We don’t treat our classmates that way,” and, one by one, he asks the children who commented on Niles’s statement to apologize to him. As they each apologize, Niles, barely looking up from his lap and with tears in his eyes, feels Rachel’s hand on his back comforting him.

Uneasy and unprepared to move forward, Mr. Hawkins asks the students to return to their seats and draw, and he requests that Niles come talk to him outside the classroom door.

Frequently, first-year teachers like Mr. Hawkins enter classrooms unprepared to appropriately address topics related to race. They also may lack cultural competence (in terms of their knowledge, skills, and dispositions) to engage children in complex matters about race and cultural differences—especially differences that depart from the White-centered ways of knowing and being that are usually unacknowledged and are operating in educational settings (and beyond). Even teachers who have been teaching for many years can be uncomfortable talking about matters of race(ism) and discrimination in their classrooms.

Because most early childhood educators are White and female, their ability to engage young children in honest and developmentally appropriate conversations about race(ism) and discrimination is vital. It is especially critical in light of the recent racist events involving the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Rayshard Brooks and countless others.

How can teachers like Mr. Hawkins help children move beyond mere apologies when they make hurtful comments involving race and other “isms”? How can they prepare to go beyond surface-level statements like “We don’t treat our classmates that way” to get to the heart of the matter? Cases like the opening vignette, which involves race, the policing of Black bodies, and stereotypes that center on anti-Blackness, require much more than swift admonishments and apologies.

Reading and discussing carefully selected picture books is one way to address matters of race(ism) and discrimination and to promote self-identity, agency, and voice in young children. Using multicultural children’s books that focus on sensitive topics requires consideration of children’s ages to determine developmentally appropriate ways to present the content. Defaulting to the belief that a child is too young is not an option; racial bias can start as early as 2 1/2 to 3 years of age.

Reading and discussing carefully selected picture books is one way to address matters of race(ism) and discrimination.

Therefore, teachers are encouraged to engage with multicultural children’s books in various formats, such as through a read aloud followed by a small group or one-on-one instruction to explore and talk about a book’s pictures, setting, characters, key problems or events, and solution. There is also an opportunity to vary (based on the ages of the children involved) the rigor of and exposure to new vocabulary and concepts such as race, racism, discrimination, inequality, and social justice. Doing so encourages children to challenge and disrupt their own racial biases and those that manifest in classrooms and society.

Here are three exemplary books that early childhood teachers can use to do just that.

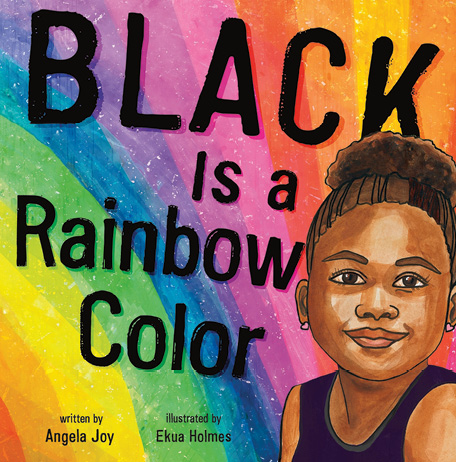

BLACK is a Rainbow Color

by Angela Joy, provides an authentic celebration of Blackness and offers all children—Black children in particular—with an opportunity to develop racial pride in the color of their skin. In the vignette, Niles’s confidence in sharing his association of the letter B to Black implies he has learned positive things about what it means to be Black, but some of his classmates have not.

by Angela Joy, provides an authentic celebration of Blackness and offers all children—Black children in particular—with an opportunity to develop racial pride in the color of their skin. In the vignette, Niles’s confidence in sharing his association of the letter B to Black implies he has learned positive things about what it means to be Black, but some of his classmates have not.

Try this! Teachers can proactively engage children with positive depictions of the color black, as portrayed in Joy’s book. They can also challenge widely held anti-Black sentiments used in everyday expressions, such as “the black sheep of the family,” and stereotypical attitudes and beliefs that “black is bad” and/or “dirty.” Also, teachers can celebrate Black people’s contributions beyond a “tourist approach” (e.g., as an add-on in February for Black History Month) to fully integrate the experiences and contributions of Black people throughout the school year. In doing so, children are exposed to the concept of curriculum as windows and mirrors, which encourages positive self-identity and positive perceptions and representations of others in the minds of all children.

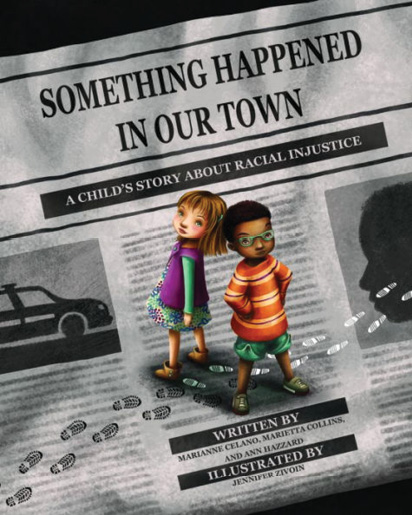

Something Happened In Our Town:

A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice

by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard, invites children to participate in a candid discussion about the many ways they are exposed to race(ism). The book deals with the sensitive topics of race(ism) and police brutality as understood from different perspectives. The two youngest characters, Emma (a White girl) and Josh (a Black boy), learn from their families about matters of race(ism) and discrimination. The book concludes with an extensive “Note to Parents and Caregivers” that provides general guidance for addressing racism with children.

by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard, invites children to participate in a candid discussion about the many ways they are exposed to race(ism). The book deals with the sensitive topics of race(ism) and police brutality as understood from different perspectives. The two youngest characters, Emma (a White girl) and Josh (a Black boy), learn from their families about matters of race(ism) and discrimination. The book concludes with an extensive “Note to Parents and Caregivers” that provides general guidance for addressing racism with children.

Try this! This book could have helped Mr. Hawkins respond to Cody’s comment about Black people and their interactions with police officers. It is important to note that police officers regularly come up in early childhood classrooms as community helpers. Teachers like Mr. Hawkins must understand that modeling open and honest developmentally appropriate conversations with young children about racial, ethnic, and cultural differences—including during a study of community helpers—is the foundation for talking about racism and discrimination. Children can be encouraged to identify injustice and take action (e.g., design a campaign to demonstrate for equality) in their community.

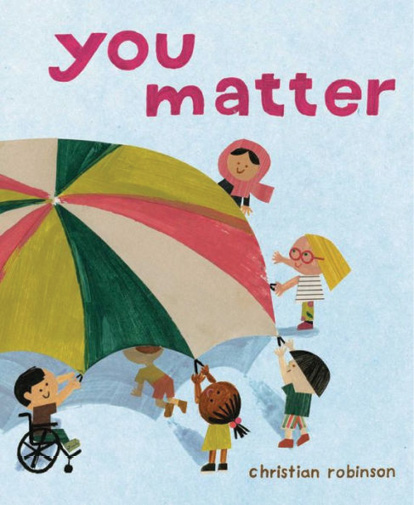

You Matter

by Christian Robinson, invites young children to see their cultural worlds in new and different ways and conveys to children what it means to matter, to have a sense of belonging, and to become whatever they believe is possible for themselves.

by Christian Robinson, invites young children to see their cultural worlds in new and different ways and conveys to children what it means to matter, to have a sense of belonging, and to become whatever they believe is possible for themselves.

Try this! Teachers can emphasize the different ways we are connected and why and how everyone matters. Mr. Hawkins could use this book to approach and join local and national discussions about the #BlackLivesMatter movement. In addition to saying, “We don’t treat our classmates that way,” he and his students could discuss the experience of being made to feel like you don’t matter because of the way you think, speak, or act. Such reflections can help children understand how people like Niles may feel when negative comments are made about the color of their skin.

Finally, it’s okay to let your students know in the moment that you will not always know or have the answers. Resources such as the books presented in this article can help teachers and children have meaningful conversations about matters of race(ism), identity, and culture. Educating children about the world in which they live serves to promote a healthy self-identity, agency, and voice that prepares and empowers our youngest citizens to advance equity in society.

Photographs: © Getty Images.

Brian L. Wright, PhD, is an associate professor and program coordinator of early childhood education in the Department of Instruction and Curriculum Leadership in the College of Education at the University of Memphis. He is also the coordinator of the middle school cohort of the African American Male Academy at the university. Dr. Wright is author of The Brilliance of Black Boys: Cultivating School Success in the Early Grades, with contributions by Shelly L. Counsell, which won the National Association for Multicultural Education's 2018 Phillip C. Chinn Book Award. [email protected]