Harnessing Potential: Integrating Technology and Media in Preschool

You are here

Over the last 20 years, the presence of technology and screen media in the preschool classroom has shifted. It was once present as a large, clunky computer station with basic “educational” gaming programs and word processing, and it was used in a separate room or at designated times each week. Now, it is a tool integrated into the teaching and learning that occur throughout each day.

As technology rapidly advances, families, educators, policymakers, and others have expressed concerns with an increase in technology and media use in the classroom—and with good reason. Overuse of technology, excessive consumption of media, and inappropriate content all have the potential to negatively influence what and how children learn and develop. However, decades of research and professional practice point to the potential of technology and media, especially when the content is of high quality, created for educational purposes with young children, and used intentionally to enhance children’s experiences and expand their potential to create and communicate.

We (the four authors) are teachers at a laboratory preschool on an urban college campus, serving children from diverse social and economic backgrounds in inclusive, mixed-age classrooms. During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, our center closed for several months, launching even the most hesitant teacher into the world of technology. The aftereffects were felt throughout the school year, as we changed many of our teaching and family communication strategies. In retrospect, these adaptations made clear some of the strategies we had begun integrating into our practices—even before COVID-19—that involved intentional use of technology and media for teaching and learning. In this article, we share four impactful, research-supported practices involving technology and media, and we offer a look at each one in action from our classrooms.

Using Technology and Media for Creative Expression

Children demonstrate remarkable adaptability when using new forms of technology for their creative processes. For example, over the years, many children have shown incredible skill in and understanding of photography with digital cameras. Now that smart devices are available, they are branching out to include creating, recording, and editing movies, music, and animation. They seem to instinctively know the basics of how to do this, and when given the opportunity, they use digital expression as readily as other art tools.

We observed this when a child in Jennifer’s (one of the authors) class combined photography with digital drawing to create new art.

Four-year-old Clara begins using the classroom tablet to take a variety of pictures and view previous classroom photos taken by Jenn during the year. She wants to add drawings to these photos, so Jenn introduces her to the “markup tool” in the Photos app. She quickly masters its use, exploring the variety of lines, colors, and other edits that she can make. She begins taking photos of objects around the classroom to serve as the background on which she can lay additional digital drawings.

When Clara finishes her work, she wants to both display it in the classroom and take it home. After an initial tutorial by Jenn, she becomes adept at sending her work from the tablet to Jenn’s laptop for printing. Once printed, they make color copies so she can display her work in both settings. Soon, Clara gains such comfort and confidence with the device and apps that she is able to teach classmates how to do the same kinds of creative expressions.

Artwork by Clara

|

|

|

|

|

|

Using Technology and Media to Support Inquiry

Often, in the pursuit of new knowledge and deeper understanding, children ask adults for answers to their questions. Now, they can also ask Google or Siri. Many educators, hoping to empower children to answer their own questions, use methods that focus on the process of discovery rather than just the end result. While looking up answers through a search engine can be appropriate, other options provide a much more robust inquiry experience. Technology-based options include child-friendly microscope attachments for devices, informational videos on a wide variety of topics, virtual tours of hard-to-reach places, and the ability to chat with experts around the world.

Sarah (another author) and her preschool class used the video conferencing skills they had learned throughout the stay-at-home portion of the pandemic to research their interests during a yearlong study of growth across several animal species.

After the discovery of squirrels’ nests, one child wonders aloud, “Do crabs lay eggs?” When this question is posed to the larger classroom group, it inspires the creation of a list of more than 10 other animals the children are curious about.

The children begin their investigation by poring over texts like Laura Vaccaro Seeger’s First the Egg and Robin Page and Steve Jenkins’ Egg: Nature’s Perfect Package. Next, the children observe the life cycles of tadpoles and chickens firsthand. After these experiences, some of the children’s questions are still unanswered: “Do foxes lay eggs?” “Do sloths lay eggs?” “Do dinosaurs lay eggs?” They also wonder where exactly eggs originate in the animals and how baby animals get into the eggs.

The next step, Sarah determines, is to connect the children with an expert in the field. Normally, she would invite an expert into the classroom for rich, face-to-face dialogue. Due to COVID-related restrictions, she adapts this interview to a video call. She arranges for a virtual meeting between the children and a team of biologists from the University of Cincinnati. Prior to the call, the children dictate a list of questions for the team. During the call, which is cast from a laptop onto a classroom television, the scientists select questions from the list and share their knowledge about how animals are born. New questions also emerge during the interview (“Do crabs make nests?” and “Are lizards pollinators?”) and are discussed. The children then share about their observations of chicks hatching and introduce one of the baby chicks to the team. Technology allows for the biologists and children to make meaningful connections and discovery through lively dialogue.

This new way for children to virtually meet with experts in their community has proved to be just as meaningful as a face-to-face meeting—and is now easier and more available to do than ever. Educators like Sarah have found this new skill and comfort with this type of meeting to be a silver lining of the pandemic, adopting it as a tool to support and expand teaching and learning.

Using Technology and Media to Document and Communicate

Many teachers have become comfortable using technology to document and showcase children’s learning and to maintain contact with families. Additionally, the immediate ability to review digitally captured images and recordings encourages children to reflect upon and extend their work, as well as collaborate and share with others across time and space. (To read more about documenting and sharing children’s learning, see Experiences Can’t Go Home in Cubbies: Using Digital Technology and Documentation to Connect with Families by Stephanie Haney.)

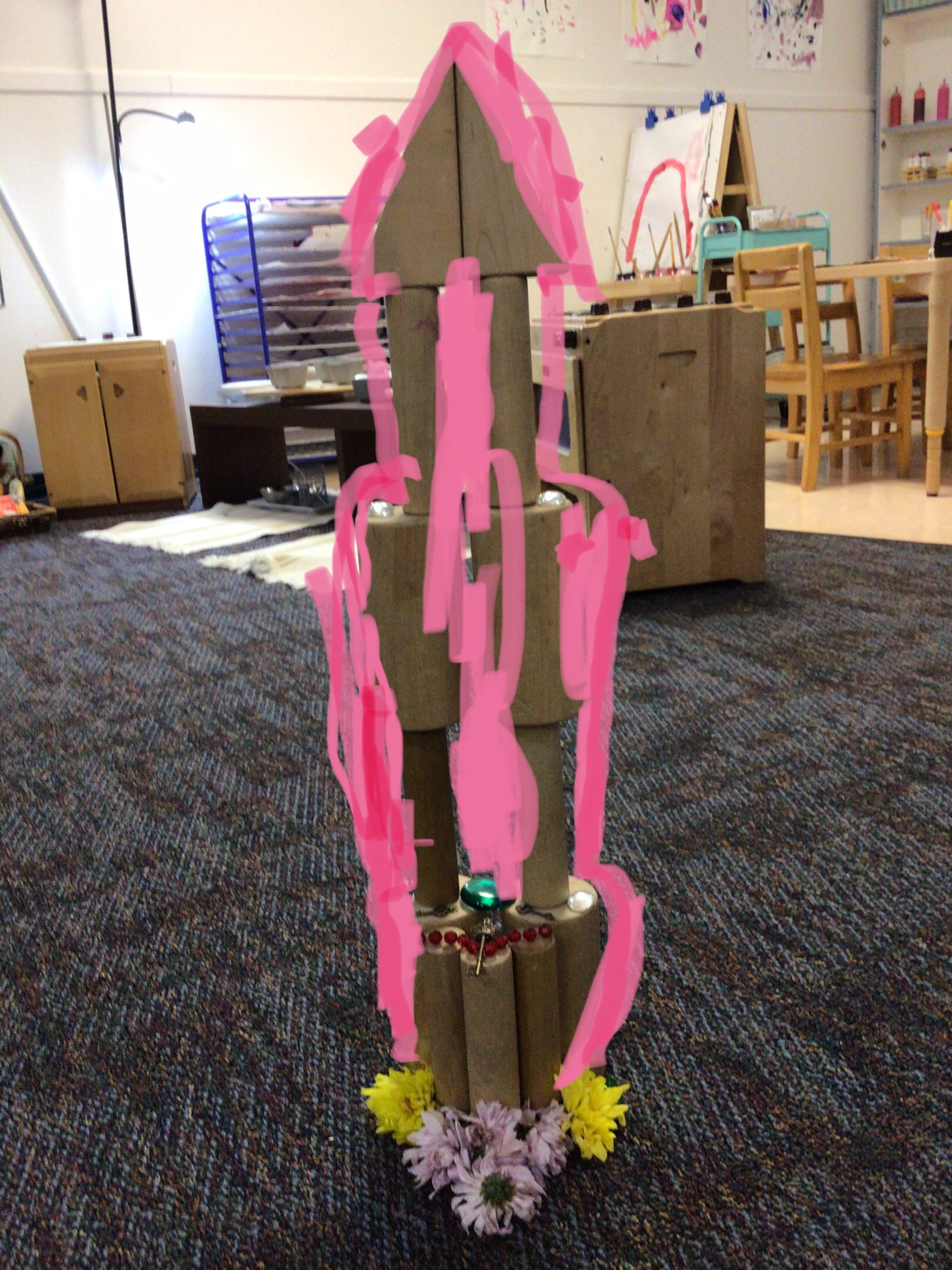

A child in Jenn’s class accessed these affordances as he built upon the drawing skills honed by Clara:

Inspired by her work, Marcus asks Clara to teach him about her digital drawing process. Once he masters it, Marcus enjoys making this new creative technique his own. He begins to document the life of the classroom: photographing classmates, occasionally giving directions to stage the shots, and labeling his work using the markup tool. As part of his process, Marcus always asks the children if he can photograph their work. In addition, he wants them to know that they can refer to his work in the event that they need to remember specific details, which echoes a regularly used classroom practice of creating and revisiting documentation in support of deepening children’s work.

Artwork by Marcus

The digital nature of the children’s work made it very easy to share with their families. This was especially important to do during the pandemic since families were not allowed to enter our center. Communication apps such as ClassDojo and photo sharing websites like Shutterfly allowed Jenn to send work to families in real time, with input from children to select which pieces to share and dictating any language to accompany the work.

Using Technology and Media to Enhance Curriculum Resources

Teachers can also use technology and media to enhance classroom curriculum materials, increasing accessibility for children and families. A digital library of familiar children’s books, such as Eric Carle’s Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? and The Very Hungry Caterpillar, are readily available through classroom devices and programs and are read aloud in many of the home languages our children speak. They benefit both multilingual and monolingual children in a variety of ways, including fostering language and literacy skills, expanding content knowledge, and building community through shared learning experiences.

In addition, websites designed as “virtual hubs” for classrooms strengthen the connection between home and school contexts. They house high-quality resources, feature classroom events, document projects, and provide consistent communication. The website for Carmen’s (another author) class included many resources that children and families could regularly access, and it was developed and updated based on the needs and feedback of families.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Carmen’s class is designed as a hybrid model: some children attend in-person, some attend virtually, and some attend both ways based on the needs of the families throughout the year. Bridging the gap between the two learning environments and building community among the children have motivated Carmen to find ways to bring interactive materials into a virtual experience for all. So every Wednesday, during a joint group time, the groups interact with each other via video conferencing displayed on a large screen.

During one Wednesday class, Carmen uses a digital presentation program (Google Slides) to create a class voting graph based on their read-aloud experiences. On the class website, she posts a link to the graph, which displays images of three of Eric Carle’s books, and she encourages children to move their digital name tag above the book they vote as their favorite. At-home learners vote before group time, and in-class learners can vote online before they come to school or by writing their names on a large paper graph (identical to the virtual graph) when they arrive at school. During group time, the votes are tallied, and the results are discussed in real time on the physical graph for those in the room and on Google Slides for those at home.

Children in both settings can actively engage with the chart and voting graph, providing a common experience to discuss during class meetings. Additionally, families of children learning in both contexts can access the chart, offering the unique opportunity for them to view and play with it together at their convenience.

The enthusiastic feedback from families and the interest of the children inspired Carmen to continue this practice into the future. The needs may adjust, but the benefits remain in a post-COVID classroom as one of many opportunities to capitalize on the affordances of technology to build community and enhance shared experiences for children and families.

Conclusion

Through reflection and intentional planning, technology and media can cease to be an additional curricular area to address or something to fear including in the classroom. Incorporating these as tools in the ways we have discussed here empowers children and educators to actively learn and grow with the support of technology and media.

Photographs: courtesy of Jennifer Horwitz and Carmen Rietta.

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See permissions and reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

This article supports the following NAEYC Early Learning Programs standards and topics

Standard 2: Curriculum

2J: Creative Expression and Appreciation for the Arts

Standard 8: Community Relationships

8B: Accessing Community Resources

Rachel Konerman is a pedagogical leader and studio teacher at the Arlitt Center for Education, Research, and Sustainability and an instructor for the University of Cincinnati’s Early Childhood Education Program.

Jennifer Horwitz is a classroom teacher and Head Start education coordinator at Arlitt Child Development Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Sarah Clancy is a lead preschool teacher at the Arlitt Center for Education, Research, and Sustainability at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Carmen Rietta worked as a lead teacher at the Arlitt Center for Education, Research, and Sustainability at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio.