Embodied Land Acknowledgment: Connecting Children to Place Through Indigenous Wisdom and Playful Inquiry

You are here

In many societies, people spend less time in relationship with nature than past generations. Along with issues of equity, this has contributed to a significant disconnect between humans and nature.

Those of us who work with young children, however, are daily witnesses to the potential for children to make meaningful and empathic connections with nature. It is not an uncommon occurrence for preschool children to sing to flowers, declare their love for worms, and build cozy homes for spiders. These connections have implications for children’s learning and development—in the moment and over time.

As teacher researchers, we began to wonder how children’s playful nature explorations could interact with and be informed by the wisdom of Indigenous people who have lived in relationship with the land for millennia, and still do. Taking note of the honored place stories often hold in Indigenous communities and of our children’s affinity for story, we decided to offer the children in each of our contexts the opportunity to connect with the natural world and with Indigenous wisdom through the exchange of stories. In doing so, we embarked on a process of fostering authentic relationships with the land and with one another, moving beyond land acknowledgment in name only and toward an ongoing embodied practice, which we define in this piece as land acknowledgment not only in the mind but also through action.

Rooted in Place and Branching Out Together

Our work takes place in three diverse contexts: Missoula, Montana; Johor Bahru, Malaysia; and Gunnison, Colorado. Honoring the varying philosophies that exist within our early childhood contexts, each of our paths toward embodied practice took different forms. As the children in each of our settings engaged in playful, nature-centered inquiry, we began seeking out opportunities for connection with our local Indigenous communities—connecting with tribe members and educators, gathering literature, visiting museums and cultural centers, and exploring the cultural traditions of the land and its people.

- In Montana, Katie and the children at Peaceful Heart Preschool, a yoga-inspired program, connected with the nature tales and ecological wisdom of the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend D’Oreille tribes as they forged place-based links.

- In Johor Bahru, Jessica and the community at Forest of Stars Children’s Centre collected historical and nature stories of the Orang Asli of Malaysia; she connected with the Orang Seletar community at Kampung Sungai Temon alongside her two children.

- In Colorado, Amanda and the children at Songbird Schoolhouse, a family child care home, explored the cycles of mountain life scaffolded by the stories of the Ute peoples.

We were brought together by a shared desire to connect more deeply with the land while immersed in a master’s program at the University of Colorado Denver in the spring of 2022. Realizing we were embarking on a journey that would far exceed a single semester, we quickly learned that we needed to approach this work with openness, patience, and a genuine desire for meaningful relationships, while also taking care not to appropriate native culture and wisdom. The following stories are a few vignettes and reflections of our ongoing exploration of land acknowledgment and Indigenous wisdom with children.

Communicating with Trees in Missoula, Montana

Inspired by Salish nature stories, the children of Peaceful Heart Preschool begin exploring what it means to feel connected to other living things. While visiting a natural space near their school, the children’s attention is piqued by a large and stately tree. Leo (age 3-and-a-half years) declares, “I feel connected to that tree! Look how big it is!”

After some speculation about just how big it really is, the children decide the best form of measurement would be preschoolers. How many preschoolers can fit around the trunk of the tree? In measuring the tree in this way, the children not only playfully engage in creative problem solving (and discover that the circumference of the tree is exactly six preschoolers), but they also create a physical link between their bodies and the tree, literally embracing the tree in a hug of joyful inquiry.

This connection continued as the children took note of other trees and began to build curiosity about trees’ perspectives, emotions, and experiences. We (Katie and the children) regularly visited the trees around our school, noticing the subtle changes that occurred from week to week. We wondered how the trees communicated with one another, if they spoke to the grass and the dandelions, and what they looked like as babies.

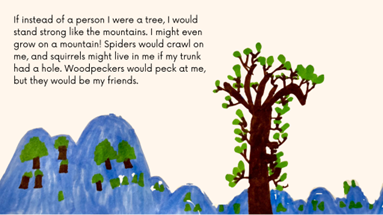

After reading the book If Instead of a Person, by First Nations author Courtney Defriend, which explores the wisdom that can be gained from taking the perspective of a tree, the children were inspired to create their own version of the story. As we structured our story, we speculated that if we were trees, we would be friends with the flowers, talk to other trees using our roots, grow fruit to share with all of our friends, and that we would “have a really good family and be beautiful.” Through this exploration, the children not only felt more connected to the trees in our place but began to blur the lines of disconnection and “otherness” that too often exist between humans and nature.

Emotional Connections to Crocodiles in Johor Bahru, Malaysia

"Tapi awak tak kacau dia, dia tak kacau awak” (If you don’t disturb it, it won’t disturb you), Dewi says playfully as we (Eddy Salim, his wife, Dewi, Jessica, and her two children, Liam and Anya) sail along the banks of the mangrove forests. We are on a boat ride with Eddy, a leader from the Orang Seletar community, and the children are eagerly hoping to catch sight of crocodiles. They have their eyes peeled as Eddy shares how crocodiles like hiding in dark water. Eddy explains that the Orang Seletar people have historically had a deep spiritual connection to nature. Prior to hunting, they would conduct rituals and offer prayers to the spirits of the ocean (sometimes manifesting as bubbles on the water’s surface). They would only take what they needed. Nothing more. As we drift by a vast blanket of bubbly waters, Liam thinks he spies a crocodile's tail.

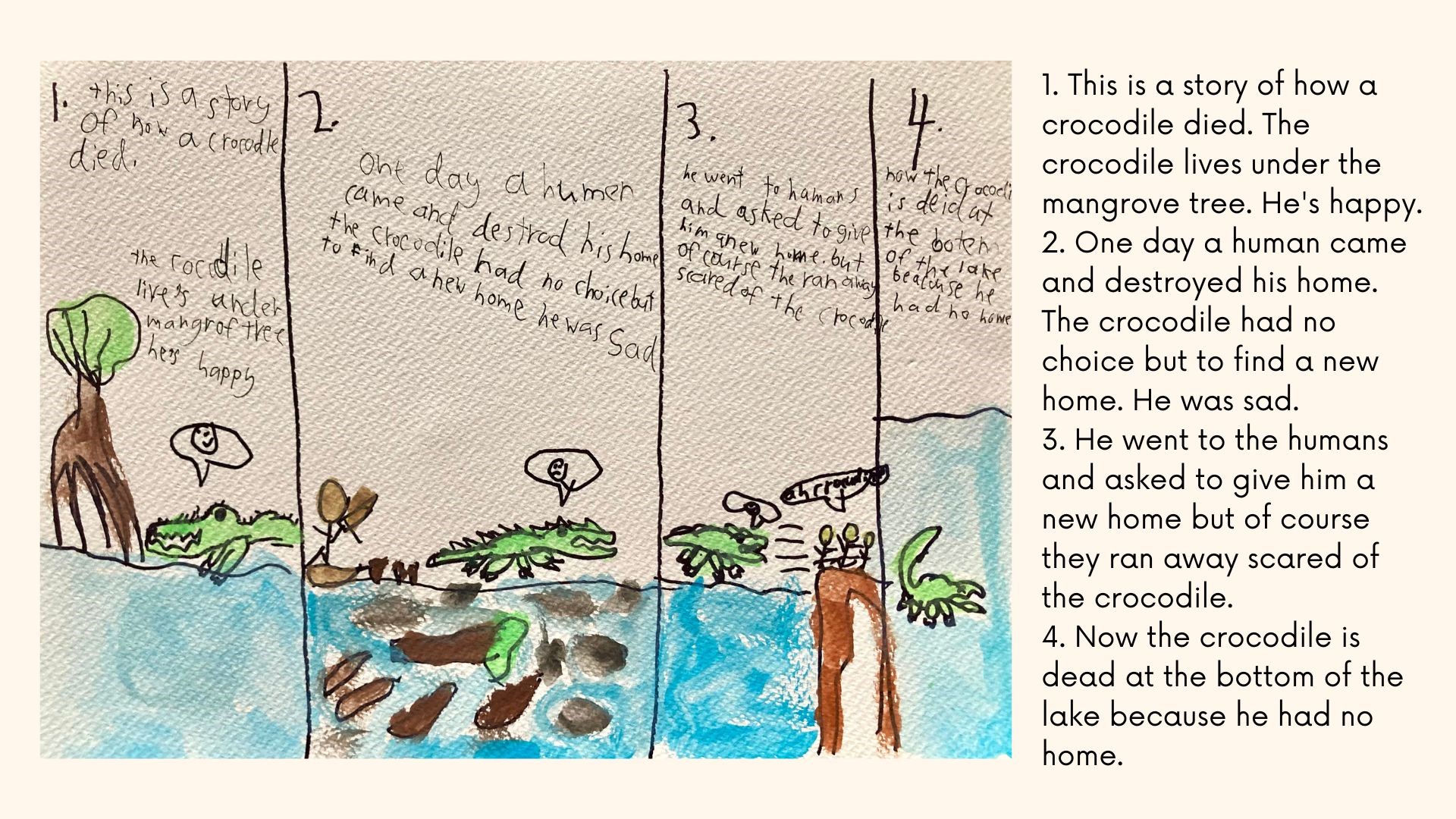

The learners of Forest of Stars Children’s Center began collecting stories to deepen their understanding of the Orang Asli community in Malaysia. One of these stories, from Eddy’s brother, Jefree Salim, was about how crocodiles are now seen in the open waters of the village due to commercial clearing of mangrove forests. After encountering this story, Liam (age 8 years) was clearly affected and found a space in his artwork and story writing to reflect, as shown in the photo below. His focus on the emotional plight of the crocodile protagonist speaks to children’s propensity to connect deeply to the more-than-human and to the natural world.

Our commitment to support children's intrinsic connection to nature guided us beyond our comfort zones and into a spirit of community, leading to connections with the Salim family and other nature-focused educators. As we began to spend more time beyond the walls of our classroom, our families expressed enthusiasm toward engaging in nature as a community, and our initial doubts began morphing into possibilities.

Exploring Cycles of Mountain Life in the Colorado Rockies

At the foot of a barely budding aspen tree, children bend, stretch, and balance their bodies this way and that. They form themselves into the varied shapes of mountains, pointed peaks, flat mesas, and narrow buttes as they explore their ideas and experiences through collaboration and movement.

Each day, as the children of Songbird Schoolhouse look around the Gunnison Valley, they see mountains of all shapes and sizes. Mountains that are not only their home but the home of myriad other species. Going beyond land acknowledgment and into inquiry and action, they also began to link the mountains with the Ute Tribe, whose ancestral homelands encompass the Gunnison Valley and beyond. Inspired by the invitation of Regina Lopez Whiteskunk, a member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, to seek connection by offering “a story for a story,” we began exploring a variety of Ute tales. As a result, the children started to imagine another side of Bear, who visits garbage cans at night, and Coyote, who peeks out from the dark roadway. They identified Spruce, Cottonwood, and Cedar not just as trees but as homes and protectors, reflecting on their own relationships with mountain life, as well as others’.

Instead of following thematic units, I (Amanda) encouraged children’s innate desire to observe nature, adding an intentional observation practice to our days, especially in relation to the cycles of change within our valley home. As we engaged in this process of looking closely at change, themes of weather, plant life, and wildlife began to appear in the children’s play.

One day while exploring clay alongside natural materials, children began to tell stories about the ways mountain homes offer protection to wildlife and humans alike, as well as the reciprocity, protection, and reverence that humans should extend to the natural world.

The children spent many days building mountain homes with blocks and loose parts. Through this playful inquiry, they began to see mountains not only as landforms, but as places of abundant life with connections to people, past and present.

Engaging in Research and Moving from Agenda Toward Reciprocity

As the children engaged in playful research and we each forged connections with our respective Indigenous communities, we came to understand that there is not one right way to connect to land and to people, but rather an endless list of nuanced possibilities. These possibilities, however, can be obscured by systems and biases in the dominant culture and in ourselves. As non-Indigenous women reaching out to Indigenous populations, we feel the tension that comes with confronting historical trauma and injustice. It is only by passing courage back and forth to each other, listening deeply, and striving for reciprocity that we have found our own joy amid the challenge. Our experiences have taught us that the practice of land acknowledgment is ongoing and should not be rushed, perhaps evolving over a lifetime.

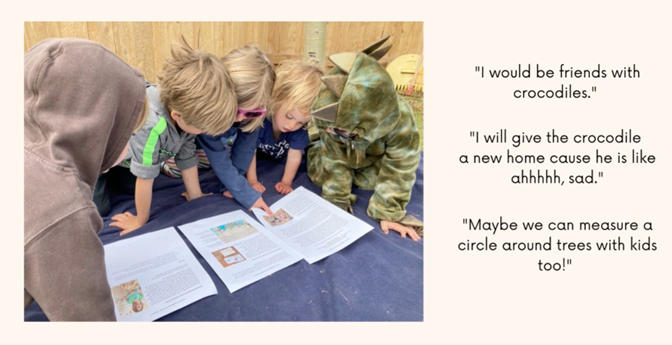

Though our research was conducted across three diverse, geographically distanced contexts, our experiences were united by a deepening connection to land, plant life, and wildlife, and highlighted children’s growing ideas around empathy, interconnection, reciprocity, and protection. Our research showed that children can explore complex subject matter through play, often guiding adults toward new perspectives. As we shared our documentation across our three schools, the children embraced curiosity about the work of their long-distance collaborators, expressing their desires to discuss their feelings for crocodiles, turn their bodies into mountains, measure trees with preschoolers, and visit a mangrove forest.

The Beginning of a Much Longer Story

The story of our collaboration is only the beginning and has no finish line and no prescribed destination. We will continue allowing it to unfold in evolutionary and serendipitous ways, continually renewing our commitments to disrupting bias and stepping outside of comfort and into complexity. We see now that disconnection from nature need not be our fate. We can look to the wisdom of children and Indigenous peoples to help mend our relationships with the earth. We invite you to join us in interconnecting children, Indigenous communities, and the land where you reside because, in the words of Robin Wall Kimmerer, “Action on behalf of life transforms. Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the earth, the earth heals us” (2015, 340).

Further Resources

- Sia, W., & S. Yap. 2021. Solastalgia: Forest, Crafts, and the People. Gerimis Art.

- Seletar Cultural and Arts Society, Kampung Sungai Temon. m.facebook.com/Seletar-Cultural-Center-243431199039727

- Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. utemountainutetribe.com

- Southern Ute Tribe. southernute-nsn.gov/history

- Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation. utetribe.com

- Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes. csktribes.org

- Séliš-Ql̓ispé Culture Committee. csktsalish.org

The authors can be reached at [email protected].

References

Kimmerer, R.W. 2015. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis; MN: Milkweed Editions.

Katie Whorrall, MA ECE, is the lead teacher at Peaceful Heart Preschool, a yoga-inspired school located on Salish, Kootenai, and Pend D’Oreille land now known as Missoula, Montana. She has devoted her teaching career to holistic, nature-centered education, and is in the process of creating a nonprofit interconnecting young children, the land, and social justice. [email protected]

Jessica Xiao Ping Lam, MA ECE, is the founder of Forest of Stars, a toddler center and creative arts space for children, where she has been committed to honoring children’s natural capacities for learning and expression over the past 10 years, realizing that a deep connection to nature is imperative to education. Forest of Stars is located on the customary territories of the Orang Seletar in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. [email protected]

Amanda Birdsong, MA ECE, is the founder and educator at Songbird Schoolhouse, a family child care home, where her teaching has become increasingly grounded in nature and place over the past 12 years. Songbird Schoolhouse is located in what is now known as Gunnison, Colorado and recognizes the Ute Tribes as the original stewards of the Gunnison Valley. [email protected]