Authentic Identity Work in a Culture of Self-Reflection

You are here

“You know I’m only 4, right?”

Sadie is a 5-year-old with many titles: older sister to two younger brothers, avid artist, confident singer, vibrant dancer, and free spirit. Sadie has big feelings and lots of love for the people she cares about, and each day, her smile and energy fill the room with excitement. Today, she and Ms. Maggie are speaking about who Sadie is and how she sees herself—her identity. At one point in the conversation, Sadie straightens up in her chair, leans close to Ms. Maggie’s ear, and confidently whispers, “You know I’m only 4, right? I need people to remember that.”

Externally, Ms. Maggie raises her eyebrows in question; however, she is truly in awe. Sadie continues, “Well, I’m trying really hard to do things on my own, but sometimes I just want to be picked up. But when I turn 5, I think I’ll be too big to be picked up. Oh, but did you know that when I turn 10, I’ll probably lose my tooth, and the tooth fairy will come? So maybe it won’t be so bad if I don’t get picked up anymore. But for now, I’m only 4, okay?”

She nods approvingly and adds a few more hearts to the page she’s working on while humming an original song that, knowing Sadie, she is confident will be the next classroom hit.

As teachers of 4- and 5-year-olds at a Reggio Emilia-inspired early childhood education program, we are always looking for ways to guide children in conversations about themselves, others, and the world. These are key components of one’s identity, which starts to form in a child’s earliest years (UNCRC 2005).

At the beginning of the 2023 school year, we decided to use self-portraiture to introduce these discussions. However, things went a little differently than we planned.

It is October, and we are staring at a round table placed in the center of our classroom, feeling anxious and uneasy about what lies before us: two double-sided mirrors, black fine-tipped pens, and 4- by 6-inch rectangles of white cardstock. This is our sincere attempt at a provocation to draw a self-portrait, and because children’s identity development is so important, we want to get it right.

A child approaches the scene, looks on briefly, then wordlessly turns away and walks elsewhere. We panic, grab the materials on the table, and replace them with a set of magnetic tiles. We share a mutual nod of agreement, “We’re not ready!”

As if on cue, three children run over as we finish setting up the base of a tile tower. “We’re just not ready yet,” Vaidehi amends, as children build and build, all the way up to the ceiling of our classroom.

Entry Points: Starting with the Wide World Around Us

Following that anxiety-filled October morning, we decided to search for entry points, or places where the children’s interests might lead us into exploring new ideas. A few weeks later, we received an unexpected gift from one of our families: a paper wasp’s nest they found during a neighborhood walk. We put it on the table and added some magnifying glasses and mark-making materials. It was immediately evident that the children were fascinated. Eventually, we extended their engagement by using a digital microscope and projector that allowed us to see the nest up close and in detail.

This experience prompted the children to take an even closer look at the living things outside. As the season shifted, they began to take walks with Ben, our studio teacher, whose enthusiasm and insight about creatures and “critters” supported our emergent curriculum as it developed along unexpected and exciting paths. The children began regularly searching for new creatures, attempting to identify familiar ones, and imagining and building shelters and homes that they thought the animals might enjoy. We were eager to support the children’s intense interest and decided a trip to our school library was in order.

One of the most influential finds from our library was a book called Incredible Animals, by Dunia Rahwan and illustrated by Paola Formica. In it, each animal has unique superpowers—flying, swimming, and echolocation, to name just a few. These superpowers make them special. The book was a hit, and we revisited it day after day, week after week, building on our and the children's enthusiasm with new information.

The children imagined what it might be like to have these traits themselves. We soon found that these conversations (typically held during our whole-class gatherings) became entry points for discussions about perspective taking and recognizing and appreciating differences. Just like the animals in the book, we talked about how each member of our community had special and unique qualities that could be considered superpowers. When we asked the children what their superpowers were, their answers included everything from “extra strong” to "being a good friend.” Over time, these dialogues, which focused on our uniqueness and the strengths that each of us shared with our community, became commonplace. Incredible Animals was powerful—and so, inspired by this book, we decided to make our own text.

The Dinosaur Guidebook, as it eventually became known, was born of the children’s interests in creatures and animals, our class's interactions with informational texts, and a growing appreciation for a diversity of appearances, abilities, and lived experiences within our class and school communities. Inspired by our Reggio Emilia-inspired approach, we supported and encouraged the children to research, design, write, and illustrate the book mostly by themselves.

By the time winter had begun in earnest, and the children’s knowledge of one another, themselves, and our communal norms had deepened. With the children’s insight, we identified the tasks necessary for bookmaking—research, illustration, writing, cover design—then invited the children to opt into task-specific teams based on their interests. In these groups, the children brainstormed what they knew and what they needed to learn more about. They also identified strengths within themselves and their peers that helped the team as a whole. When inevitable challenges arose, like figuring out exactly where to find answers to tough questions, the children were able to corral their resources and find solutions that led them to reach out to other teams, other teachers and children in our school, and beyond. They even created a podcast—but that, perhaps, is a story for another time!

Giving Identity Another Go

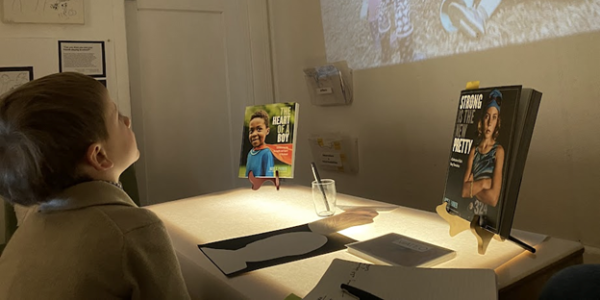

By March, we finally felt ready to dive into investigations of identity and portraiture, which had felt foundational to our teaching practice and had intrigued us since early fall. We began anew with two anchor texts—The Heart of a Boy: Celebrating the Strength and Spirit of Boyhood and Strong Is the New Pretty: A Celebration of Girls Being Themselves; both are photography books by Kate T. Parker. On each page, a portrait of a child is paired with the child’s words about themselves. We treated these images as visual texts, pointing out that photos only reveal a small piece of who a person is. We wanted to emphasize to the children that there is more to a person than meets the eye and that this is true for everyone.

When it was time for more intimate conversations, we decided to set up shop in the cozy room—a small nook in our classroom where we could close the sheer, gauzy curtain and invite deep focus. These conversations, we intuited, would necessitate vulnerability and reflexivity, best served by a degree of privacy. As we had done in October, we once again, we intentionally chose an array of materials: the books mentioned above, individual family photo albums (collected at the beginning of the year), and a printed picture of each child (also from the beginning the year). Each picture was attached to a blank canvas and could be flipped up to reveal the canvas underneath. Above the small table, where the children sat, we projected pictures of them, taken over the course of the year. While the children took in the photographs, we invited their commentary, using prompts such as

- “When people see or meet you, they can only see things like your face, eyes, and hair. However, they don’t see what’s inside your beautiful mind and heart. What would you like to share with others about yourself?”

- “What is your story?”

- “What do you care about?”

- “Tell me about some of your strengths. What about some challenges you face?”

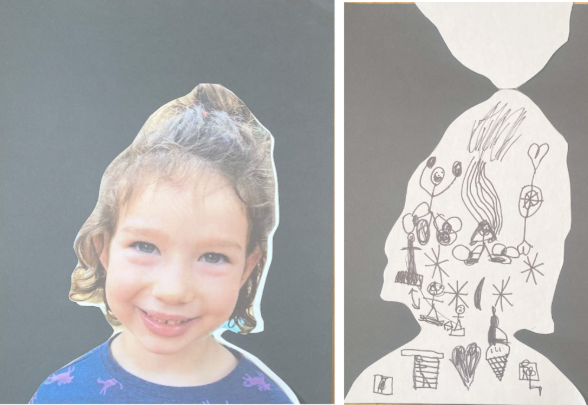

We created space and provided support for the children to share about themselves through their own drawings and words (see “Farryn’s Story” below). Then, we listened as they worked and took notes, which became our documentation.

Farryn’s Story

There is love inside my heart.

I also love ice cream.

I like to look at stars—it looks like movies: the moon and stars.

I love going to the children’s museum—it gets my brain excited. My favorite is the climbing structure.

I am good at climbing and drawing.

I want to learn to run fast. I want to run races like Mama. I was so tired when I was running the race in Arizona. I don’t want to be so tired when I run.

My favorite thing to play with Finlay is making a pillow pile and playing Floor Is Lava.

I don’t always like being the big sister because I have to do everything, like today I had to pick up all the toys.

We end this story as we began, with a note from Sadie. She would like readers to know the following: “I have got lots and lots of love. It means I have a lot of cares in my body. Sometimes, I give the caring to people who aren’t even nice because maybe they are just shy or something.”

Photographs courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

UNCRC (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child). 2005. “Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood.” General Comment No. 7. United National Digital Library. digitallibrary.un.org/record/570528#record-files-collapse-header.

Vaidehi Desai, MEd, holds degrees in special education and early childhood education and is a teacher at Newtowne School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She has worked as a special education and early childhood educator in different settings, including preschools in India and the United States. Vaidehi’s work is deeply rooted in anti-bias education and supportive social learning. This helps her to critically evaluate her practices in the classroom and to develop a strong image of the child, honoring them as valuable citizens with inherent and undeniable rights. [email protected]

Margaret Oliver is a graduate of Clemson University’s College of Education. She is committed to working with inclusive programs that embrace diversity and equity. She channels her passion for the arts to design engaging activities while integrating these core values into all aspects of her work. Margaret is currently a lead prekindergarten teacher at Newtowne School, a Reggio Emilia-inspired program in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is pursuing a master’s degree at Boston University in the Curriculum and Teaching Program. [email protected]