Listen to What We Hear: Developing Community Responsive Listening Centers

You are here

Jasmine’s eyes light up as she hears her mother’s voice read a book in Arabic through the class tablet. Her teacher, Ms. Bloom, holds open the matching book as Jasmine and three of her classmates crowd around to see the pictures in Al-Alwan, Al-Ashkaal, Al-Arqam: Learning My Arabic Colors, Shapes, & Numbers, by Asma Wahab. “That’s Jasmine’s mommy reading to us,” squeaks Grace, one of the children crowded around the book.

“It is! We can listen to your grandma read next, Grace,” says Ms. Bloom.

Jasmine’s class is one of seven at the Rainbow Center in east-central Indiana that is taking advantage of new listening centers. Thanks to a 14-week partnership with Ball State University’s Early Childhood, Youth, and Family Studies Department, children at the Rainbow Center can now hear books read by members of their families and the community who share their cultural heritage.

Books and other texts have the potential to reflect identities, experiences, and communities (Bishop 1990). When they do, they can appeal to readers of all ages and prompt literacy enjoyment and growth. However, inequities exist in who is represented in these books and how they are portrayed. This disparity extends to the materials and learning centers found in early childhood classrooms.

We set out to address this challenge. In the fall of 2019, one class of 21 early childhood teacher candidates (with us, their teacher educators) partnered with 14 early childhood teachers at Rainbow Center to design and implement community responsive listening centers. The goal of this partnership was twofold: to offer a unique learning experience to future and current educators, and to support the center’s efforts to enhance its literacy and language resources to be responsive to the children and families it serves. Together, we created listening centers that aimed to achieve responsiveness through practices and materials supported by emergent literacy theories and current research.

Located in a rural setting near our university, Rainbow Center serves approximately 100 children from six weeks to age 5 in seven classrooms. Four languages are spoken at the center: English, Spanish, Arabic, and Mandarin. There are two preschool rooms (children ages 3 to 5 years), one infant room (children 6 weeks to 12 months), and four toddler rooms (children ages 1 to 3 years). Each room has two teachers and a varying number of children, depending on the mandated child-adult ratio. As part of our partnership, three teacher candidates were assigned to each classroom; they were intentionally paired with classroom teachers to design and implement a listening center specific and unique to that classroom of children. Their planning, practices, and reflections were guided by a single question: “How can early childhood teachers create listening centers that are community responsive and that foster early literacy development?”

Community Responsive Early Literacy: The Value of Listening Centers

Advancing equity and developing and sustaining anti-bias early childhood programs have been goals of the early childhood field for decades (NAEYC 1995, 2019; Derman-Sparks & Edwards with Goins 2020). This work includes tailoring learning experiences to the children in a classroom or program so that their funds of knowledge (Moll et al. 1992) and identities are affirmed. Building upon the ideas of being culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings 1995), culturally responsive (Gay 2000), and culturally sustaining (Paris 2012; Paris & Alim 2017), we refer to this work as being community responsive (Duncan-Andrade 2016). To be community responsive, educators must engage with and take into account the cultural demographics of their particular locales.

When children have access to culturally relevant literature, academic achievement significantly increases (Clark 2017). However, the landscape of children’s literature remains remarkably resistant to change. While demographic data show a “majority-minority” student population wherein Latino/a, Black, Indigenous, and Asian children surpass the number of White children in America’s public schools (NCES 2015), children’s literature remains overwhelmingly White (SLJ 2019).

Pre- and in-service teachers must be prepared to offer instruction and learning experiences that are relevant to the lives of all children. This is especially true for instruction that affirms previously ignored or denied identities and existences (NBPTS 2002; NAEYC 2019, 2020). Early childhood educators can offer inclusive language and materials that actively represent all children and families while simultaneously fostering the critical thinking and early literacy skills connected to academic success in kindergarten and beyond. These practices need to encompass all foundational early literacy skills, including oral language development (Paris 2005; NAEYC 2009; Dickinson, Nesbit, & Hofer 2019).

Explicit instruction in early literacy and language areas such as phonological awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and listening comprehension is necessary for literacy learning and success (Teale, Whittingham, & Hoffman 2018). The field has consistently recognized that enacting engaging, well-conceived listening centers is an effective way to promote these early literacy skills with young children (Schickedanz & Collins 2013; Fisher & Frey 2019). Listening centers are physical areas (or stations) in classrooms. They are designed to help children work collaboratively (in large or small groups) as they listen to oral stories, songs, rhymes, or books through technological means and then engage with what they listened to through exploring, discussing, or creating with others. Sometimes, children look at a written text that matches what they are hearing. Sometimes, they engage solely through listening, talking, and moving.

Planning and Implementing Community Responsive Listening Centers: One Program’s Journey

The children at Rainbow Center have a variety of interests, strengths, needs, and characteristics. Because of this and the number of languages spoken, each listening center had to be unique. We wanted to create centers based on the specific children at this center rather than on the generic, monolithic, identity-based assumptions or stereotypes that can occur in early education settings (Gilliam et al. 2016). To ensure this occurred, our teacher candidates embarked on a study of community engagement and culturally responsive and sustaining practices before they were paired with Rainbow Center teachers. They also undertook a systematic analysis of power and privilege and considered how each of these factors shapes educational experiences and outcomes.

Once paired, Rainbow Center’s classroom teachers brainstormed with teacher candidates about what they would ultimately like to see in a listening center. They shared current and ideal literacy resources in the classroom; they gathered information to learn more about children’s interests, current knowledge, and prior experiences; and finally, they thought through how to design each listening center to best utilize classroom space.

Each team also interviewed families, explaining the idea behind building listening centers in the classrooms. Families excitedly shared about their children, what they (the adults) would like to see in a new listening center, and how they would best like to be involved. Besides interviewing families at drop-off and pick-up times, informational fliers and questionnaires were sent home with children to encourage families to offer additional ideas.

Designing the Listening Centers

Each classroom team first assessed the strengths and gaps in their current classroom materials. They then began planning the design and content of their listening centers. As the overseers of this partnership, we (the authors) asked the teams to consider several factors, including

- children’s progression in early literacy and language development

- current classroom resources

- family interview results

- children’s interests

- effective literacy practices

- effective community responsive practices

We wanted the centers to be inviting spaces for children. We also requested that they offer a wealth of materials, including oral stories, songs, rhymes, and both digital and print books. The latter needed to include board books, interactive books, and wordless books, all from a variety of genres.

Acquiring Funding

Because listening centers require materials and resources, we (the authors) applied for and obtained a grant through the university. This grant allowed each room to buy a 12-inch tablet, $400 in furniture (tables, rugs, and storage), $100 in interactive materials (scarves, puppets, felt boards, and balls), $100 in technology supports (tablet stands, tablet covers), and $400 in books. While the funding was useful and exciting to all participants, listening centers can be created with fewer resources. All that is really needed is a recording device, the public library, and community connections.

With their budget in mind, each team developed a plan for the physical layout, technological needs, and interactive materials needed for their listening center. Although every team had to consider where to place their centers, what furniture they needed, and what technology and interactive materials best fit the needs of the children, each classroom required a different plan. For example, a toddler room may be better served by a sound system, circle rug, and scarves and balls to encourage movement; meanwhile, a classroom of 4-year-olds may be better served with a sound system, large tablet for interactive storybooks and oral storytelling, and a child-sized circular table and chairs for increased engagement and collaboration.

When all their planning was complete, each teaching team drew a blueprint of their classroom’s listening center and compiled a list of materials to buy. However, the most important item could not be bought. For the voices that would narrate our books, we turned to the community.

Finding Storytellers

To incorporate effective literacy practices and ensure community responsiveness, listening center content must be inclusive and unique to each classroom. Before purchasing reading material, our teams of teacher candidates and classroom teachers compiled lists of potential books using well-established and respected lists of quality children’s literature. These included the American Library Association Youth Media Awards, the International Board on Books for Young People Honour List, and the Social Justice Books Booklists.

Books were evaluated using several criteria, including

- the extent to which the experiences and identities of children in the classroom were reflected

- the extent to which the books reflected the interests of families

- the extent to which books offered new windows into the experiences of others

- the extent to which books were written in “own voices”

Teams then searched for and acquired access to developmentally appropriate, high-interest, and community-relevant materials for each listening center. (For instance, because the barbershop was a central meeting place in this community, teachers intentionally selected Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut, by Derrick Barnes.) Yet as they searched through book and song recordings available online or from commercial vendors, our teams noticed something: the majority of items available were read, talked, or sung by people who did not look or sound like the children and families of Rainbow Center. Given what we know about the lack of representation of diverse social identities in children’s books, this “finding” was expected. Rather than rely on these existing materials, we decided to ask families and community members to record the listening center content on our tablets.

Connecting with Families and the Community While Socially Distanced

Learning occurs in many settings, including in homes and communities. Particularly now, as we reemerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, listening centers can embrace and showcase the learning that occurred at home, while many early learning programs were closed. In this way, educators can connect to families’ and communities’ funds of knowledge to foster children’s learning in the classroom.

When children, families, and other adults cannot physically enter classrooms, teachers must be creative in connecting home and school life. Community responsive listening centers are a great way to bring families and community members into classrooms safely:

- Ask families to send in videos or audio of them greeting the class.

- Have families send in video or audio recordings of them reading their favorite books from home or a book their child borrowed from the classroom library.

- Send a tablet home and ask families to make recordings, then return the tablet. Children can hear, sing, and read along with the important adults in their lives while still being safe during a pandemic or other challenging time.

To attract community interest and involvement, Rainbow Center sets up an open house at the adjacent elementary school. Teacher candidates and classroom teachers transform the library into a book display and recording studio. As people mill about, one of the teacher candidates approaches an adult she does not know.

“Hi!” she says. “We are creating listening centers for all the classrooms at the Rainbow Center next door. Would you like to read a book or tell a story? I’ll record it on the tablet, and then the children will get to hear it read to them as they look at the book.”

The adult stops and looks at all the books, a small smile on her face. “I can read any of these, and the kids will get to hear my voice reading?” She picks up I Love My Hair, by Natasha Tarpley. “You have my favorite book.”

She then turns to her elementary school-age children, who are browsing the tables full of books. “They can read too,” she says, thereby extending Rainbow Center’s outreach to community members of all ages.

Teacher candidates held “recording sessions” at Rainbow Center, the local community center, and the elementary school. Community members selected books from a diverse collection of high-quality children’s texts to read and record (see Books Chosen for Listening Centers below for a sampling), or they brought a favorite book to read. Some also generously and spontaneously shared oral histories of the neighborhood and sang songs. The listening centers were now filled with meaningful content shared through the voices of family and community members rather than people with whom the children had no connection.

Launching the Centers

Ms. Dean, one of Rainbow Center’s toddler teachers, waves a bright blue scarf high in the air as Ms. Cassidy (a teacher candidate) points to the blue gondola car in Freight Train/Tren de Cargo, by Donald Crews. Narrated by Juliana’s dad, the book plays on the tablet in both English and Spanish while Juliana and three of her classmates wave their own blue scarves vigorously.

As Juliana’s father’s voice introduces the purple box car, Ms. Cassidy turns the page. Ms. Dean quickly puts down the blue scarf to pick up the purple one, swishing it around to create big loopy circles in the air. Juliana and the other toddlers immediately scurry to find their own purple scarves on the floor and attempt their own loopy scarf-circles. Neither Ms. Dean nor Ms. Cassidy speaks Spanish, but they both smile with encouragement and joy as Juliana shouts out the Spanish word for each color as she finds scarves to match the train cars in the book.

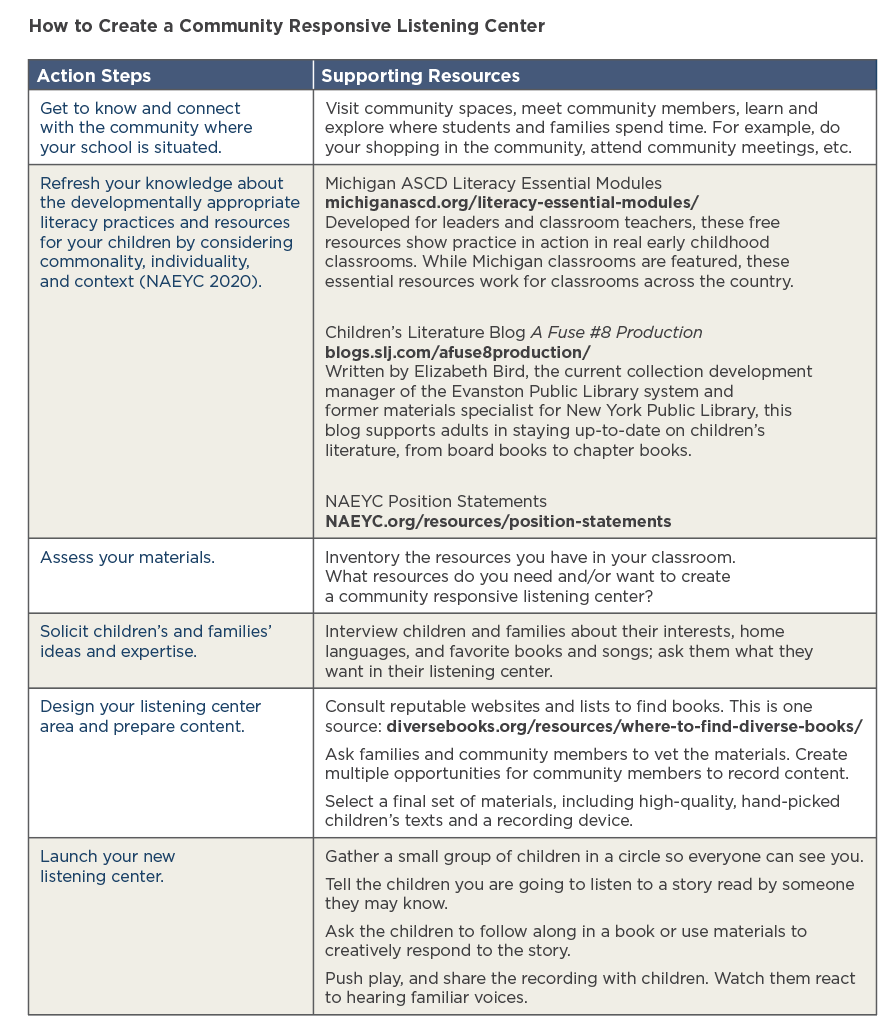

Too often, educators may believe that families and communities are not interested in engaging in literacy practices or that it will be too difficult to tailor classroom experiences to the cultures and contexts of children’s lives. Our project with Rainbow Center disproves these ideas. Families and community members like Juliana’s dad were thrilled to be involved—especially when treated as partners who can significantly and meaningfully participate in children’s learning. (See How to Create a Community Responsive Listening Center above.)

Too often, educators may believe that families and communities are not interested in engaging in literacy practices or that it will be too difficult to tailor classroom experiences to the cultures and contexts of children’s lives. Our project with Rainbow Center disproves these ideas. Families and community members like Juliana’s dad were thrilled to be involved—especially when treated as partners who can significantly and meaningfully participate in children’s learning. (See How to Create a Community Responsive Listening Center above.)

It took about 14 weeks from idea to inception for the children at Rainbow Center to begin using their listening centers. Once they became part of the classroom, centers were predominately used with an adult to coincide with each classroom’s curriculum themes, schedules, and student requests. At the end of the project, families and community members were invited to browse through the listening centers during an open house, where the teaching teams showcased their centers and offered opportunities for families to use the materials with their children.

Listening Centers as a Community Reflection

So often, we may forget that families are experts in their own right. This project influenced how current and future early childhood teachers thought about and engaged with their community as an asset to children’s development and learning. The listening centers they created were uniquely reflective of the children in a particular classroom: each center authentically incorporated classroom families and the larger community while effectively applying emergent literacy theories and research-based literacy practices.

Early literacy has everything to do with linking school and culture together in meaningful ways.

Teacher candidates and classroom teachers came to understand the political nature of early literacy, taking seriously the potential and real harm done to children when literacy practices—and schooling more broadly—attempt to separate children’s funds of knowledge and cultural wealth from their learning (Freire 1970, 1985, 2000; Moll et al. 1992; Yosso 2005). As one of the teacher candidates participating in this partnership said: “Early literacy has everything to do with linking school and culture together in meaningful ways. We wanted there to be a space where the children could hear their community represented inside the classroom as well as the different cultures within their families.”

To promote genuine literacy learning experiences, educators need to be knowledgeable of and responsive to the strengths, interests, values, and needs of a community. They need to be attuned to children’s and families’ cultures, identities, and home environments. In practice, this means that educators must affirm, introduce, value, and reinforce multiple forms of literacy and refrain from normalizing only dominant ways of knowing (Kirkland 2013; Paris & Alim 2017). It also means that educators need to dig into the community and work to build authentic and deep relationships with families.

“I’m learning a lot about what being a community responsive teacher means,” a teacher candidate said. “It is an ongoing process that needs constant attention and adjusting. All of these ideas and philosophies and strategies need to be something that is not only a part of who I am as a person and a teacher and a part of my belief system, but something I do and enact in my day-to-day life and in the classroom.”

Choosing Books for Listening Centers

When evaluating books for inclusion in a listening center, it is important to ask three key questions:

- Does this book reflect the children in my classroom?

- Does it offer an important window into a different perspective that they may not have experienced?

- Is it responsive to children in my class and the surrounding community?

The teaching teams at Rainbow Center selected over 90 books for their listening centers. Here are some that may help you start your own list.

- Baby Goes to Market, by Atinuke (2017). Set in a busy Nigerian marketplace, this beautiful book offers rhythmic language, humor, and an introduction to numbers.

- Love Makes a Family, by Sophie Beer (2018). By showing simple, joyful activities done by many different kinds of families, this inclusive book demonstrates that the most important part of a family is the love they share.

- Little You, by Richard Van Camp and illus. by Julie Flett (2013). An enchanting book that can be read or sung to the smallest children, this heartfelt text won the 2016 American Indian Library Association Award for Best Picture Book.

- What Is Light, by Markette Sheppard and illus. by Cathy Ann Johnson (2018). A lyrical book that emphasizes the salient moments and simple pleasures in children’s lives, this text reveals all types of light in the world.

- Holi Colors, by Rina Singh (2018). In this board book of bright photographs and playful rhymes, Holi (the Hindu celebration) is featured as a magnificently fun way for children to explore colors.

Photographs © Getty Images; courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Clark, K. 2017. “Investigating the Effects of Culturally Relevant Texts on African American Struggling Readers’ Progress.” Teachers College Record 119: 1–30.

Derman-Sparks, L., & J.O. Edwards, with C. Goins. 2010. Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Dickinson, D.K., K.T. Nesbitt, & K.G. Hofer. 2019. “Effects of Language on Initial Reading: Direct and Indirect Associations Between Code and Language from Preschool to First Grade.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 49: 122–137.

Duncan-Andrade, J. “All Together Now: Academic Rigor and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy.” YouTube video, 1:21:48. Teach for American Events. February 11, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzNl4unAe20

Fisher, D., & N. Frey. 2019. “Listening Stations in Content Area Learning.” The Reading Teacher 72 (6): 769–73.

Freire, P. 1970/2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 30th anniversary edition. New York & London: Bloomsbury Press.

Freire, P. 1985. “Reading the World and Reading the Word: An Interview with Paolo Freire.” Language Arts 62 (1): 15–21.

Gay, G. 2000; 2010. Culturally Responsive Teaching. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gilliam, W., A. Maupin, C. Reyes, M. Accavitti, & F. Shic. 2016. Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions? New Haven, CT: Yale University Child Study Center.

Kirkland, D. 2013. A Search Past Silence: The Literacy of Young Black Men. New York: Teachers College Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. 1995. “Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy.” American Educational Research Journal 32 (3): 465–491.

Moll, L.C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, & N. González. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory into Practice 31 (2): 132–41.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 1995. “Responding to Linguistic and Cultural Diversity: Recommendations for Effective Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

———. 2009. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children Birth through Age 8.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

———. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

———. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. 2002. What Teachers Know and Should be Able To Do. Arlington, VA: NBPTS.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2020. “Racial/Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools.” Accessed May 2020, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cge.asp.

Paris, S. 2005. “Reinterpreting the Development of Reading Skills.” Reading Research Quarterly 402 (2): 184–202.

Paris, D. 2012. “Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Needed Change in Stance, Terminology and Practice.” Educational Researcher 41 (3): 93–97.

Paris, D., & S. Alim, eds. 2017. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. New York: Teachers College Press.

Schickedanz, J.A., & M.F. Collins. 2013. So Much More than the ABCs: The Early Phases of Reading and Writing. Washington, DC: NAEYC .

School Library Journal. n.d. “An Updated Look at Diversity in Children’s Books.” Accessed June 19, 2019. https://www.slj.com/?detailStory=an-updated-look-at-diversity-in-childrens-books.

Sims Bishop, R. 1990. “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom 6 (3): ix–xi.

Teale, W.H., C.E. Whittingham, & E.B. Hoffman. 2018. “Early Literacy Research, 2006-2015: A Decade of Measured Progress.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 20 (2): 169–222.

Yosso, T. 2005. “Whose Culture has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race, Ethnicity, and Education 8 (1): 69–91.

Emily Brown Hoffman, PhD, is assistant professor in early childhood education at National Louis University in Chicago. She received her PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago in Curriculum & Instruction, Literacy, Language, & Culture. Her focuses include emergent literacy, leadership, play and creativity, and school, family, and community partnerships.

Kristin Cipollone, PhD, is associate professor of curriculum and instruction in the Elementary Department at Ball State University and the director of the Schools Within the Context of Community program. Her research interests include the development of equity-focused educators, preservice teacher dispositions, and the ways in which inequality is (re)produced in and through schooling.