Tapping Playful Research to Create an Inclusive Classroom Community (Voices)

You are here

Morgan is a third-grade student at the International School of Billund in Denmark. Not long after he joins my class, I notice that he struggles with navigating relationships, moderating his emotions, and following classroom rules. My coteacher, Rasmus, and I know that Morgan’s social difficulties are not new. Since kindergarten, he has had a hard time making the compromises needed for play, and his classmates view his behavior as unpredictable, with angry outbursts. In addition, Rasmus worked with Morgan last year and has seen his struggles firsthand.

Morgan loves to spend focused time drawing and painting, working with various materials, and making books. Yet when it is time to move on to a new activity, he often refuses. On this day, he is reluctant to leave the art center. After 30 minutes of negotiation and conflict, he agrees to participate in our new classroom activity, then spends only five minutes on it. Not knowing how to interact with or support him, the other children tend to avoid him. Morgan has a circle of three friends he made in kindergarten, who he is still close with, but he is not branching out socially.

In my school, the International School of Billund (ISB) in Jutland, Denmark, we value playful education. Learning through play, for us, means offering playful experiences designed to make everyone feel included as they grow, learn, and engage in the community of learners. The design of these experiences is driven by choice, wonder, and delight, which are our indicators of playful learning (Baker & Salas 2018).

ISB values teacher inquiry. Since 2014, the teacher researchers at our school have teamed with university-based researchers from the Pedagogy of Play Project at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education to develop a shared understanding of what it means to make play the heart of our school. Since joining ISB in 2016 as a primary years teacher, I have participated in teacher research. For the past two years, I have facilitated a teacher research study group, where teachers can research questions about playful learning based on their interests and classroom needs. In these groups, teacher researchers reflect on and inquire into topics that can help both their practice and students’ experiences.

This year, the focus of our teacher research group has been playful education and how to build a culture of learning in our classes. Some teachers have focused on creating this culture by examining how students follow the instructions they give. Others have focused on the importance of viewing mistakes as learning opportunities rather than failures. Still others have examined how to build kind and tolerant learning environments where everyone is included and accepted.

During the first meeting of our study group, I described my interest in inclusion and how I puzzled about supporting Morgan, who has a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Based on my observations and interactions with him and his classmates, I discovered that he felt left out of the classroom and had a hard time participating in class activities. Classmates felt that he was unpredictable in his reactions so they preferred to avoid interacting with him. How, I wondered, could I develop an inclusive classroom that would celebrate Morgan’s strengths and encourage him to engage with the other children?

Throughout the year, ideas from the study group helped inform my strategies to create an inclusive setting for each and every child in my class. In this article, I share what my coteacher and I did to support Morgan’s feelings of inclusion. I outline the background and methodology of my research, share the documentation we collected, and reflect on our outcomes.

Essential Components of an Inclusive Learning Community

Since I started engaging in teacher research, I have been interested in the way our school can support and accommodate children with barriers to learning; specifically, how playful education, agency, and choice can affect and promote inclusion.

How to educate and care for each and every child have become priorities around the world. This connects with one of the tenets of developmentally appropriate practice—that learning experiences should be meaningful, accessible, and responsive to children both collectively and individually (NAEYC 2020). Along with efforts related to race, culture, gender, and income level, many have worked to create policies and use practices to protect, educate, and support individuals with learning barriers or disabilities. One particular philosophy is that children with and without disabilities should be educated together and that there are benefits for everyone in an inclusive educational system and classrooms (Brillante 2017; Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, n.d.).

Inclusion is critical for learners with diverse abilities, strengths, and needs. There are a few reasons why: Research shows that when children with disabilities experience an effective, inclusive early education, they “are able to fully access and participate in opportunities to learn, develop, and connect” (Catlett & Soukakou 2019). Studies also show that when children without disabilities experience an effective, inclusive early education, they are able to grow and connect with their peers (Odom, Buysse, & Soukakou 2011; Green, Terry, & Gallagher 2014; HHS & ED 2015). In contrast, not including children with disabilities can have long-term, negative effects on them (Meyer & Ostroksy 2013; Wells 2014). This means that inclusion is essential to achieve equity in education.

In Denmark, the focus on inclusion is great. Due to the Folkeskole reform (Nusche et al. 2016), fewer students are joining special schools each year and are instead participating in inclusive educational settings. Yet despite this and other encouraging trends worldwide, stigmas remain, and obstacles continue to exist. Too often, children with disabilities are excluded from high-quality experiences that will help them grow, learn, and engage with others as well as feel accepted for who they are (Agena, Boecker, & Churchill 2021).

Features of Inclusive Environments

To ensure that children with disabilities are welcomed and supported within the classroom environment, the philosophy of inclusion needs to be translated into practice. It is not enough just to have children with and without disabilities together in the same setting. More has to be done to ensure their participation, progress, and social and emotional access. As Brillante (2017) states, children with disabilities need “a diverse group of peers and adults with whom to form relationships and friendships and learn social interactions” (32).

Effective inclusive early learning environments share several features. These include

- a sense of belonging. A major goal of inclusive settings is to promote a sense of belonging, membership, and positive social relationships for children with and without disabilities (DEC/NAEYC 2009, 2). Individual differences are acknowledged and celebrated, and each member of the learning community has ample opportunities to participate and have agency in their learning and interactions. Each child should feel physically and psychologically safe to be who they are in their early learning environments (Sreckovic et al. 2018; Catlett & Soukakou 2019).

- a focus on each child’s strengths and interests. Not only does an inclusive environment recognize individual differences, it also taps into the assets and interests of each learner (NAEYC 2019). Inclusive teachers learn about children’s unique skills, talents, and passions and use that information to create engaging learning experiences. They use a learner’s strengths to individualize these experiences rather than planning and teaching from a deficit-based perspective (Sreckovic et al. 2018).

- playful education. Play is a crucial part of teaching and has an effect on classroom engagement (Walsh, McMillan, & McGuinness 2017). Research on learning through play and the benefits of it beyond early childhood has increased in recent years (Zosh et al. 2017; LEGO Foundation 2017). In Denmark, supporters of this movement include the International Baccalaureate Organization (2016) and the Danish Folkeskole, or public schools (Undervisnings Ministeriet 2010).

Having delved into the literature, I began to look at specific ways to help me understand and promote an effective, inclusive classroom. Based on my initial wondering about Morgan, I crafted three research questions to gauge the effects of a playful, inclusive classroom on his sense of belonging:

- How can I draw on and plan for Morgan’s strengths and interests to develop his sense of belonging and engagement in this classroom community?

- How can a playful learning approach help?

- How will this playful approach influence Morgan’s relationships with others in the learning community?

Methodology

Since 2014, ISB has participated in Playful Participatory Research (PPR). Just as children experience agency, wonder, and delight when learning through play, teacher researchers can also integrate playfulness into their work. PPR encourages us to imagine possibilities, experiment with materials and ideas, and have a positive and inquisitive stance in our work. It is a reflective and playful way to explore a puzzle or to try out a new idea in our teaching. (For more about PPR, see “Inquiry Is Play: Playful Participatory Research” in the November 2018 issue of Young Children and the Pedagogy of Play website at pz.harvard.edu/projects/pedagogy-of-play.)

Setting and Participants

In Denmark, education begins as early as 9 months, when most children join a publicly funded early learning program. By age 3, 98 percent of children join public kindergartens. In both of these venues, the emphasis is on developing social skills. When children reach age 6, they begin their first year of primary school, where testing and rankings are avoided. Rather, children are challenged to think creatively and to work in groups. Instead of memorizing facts, they are taught to solve problems and grow in their critical thinking.

At ISB we follow the International Baccalaureate Programme, which is a student-centric approach that focuses on developing caring, inquiring, and knowledgeable young adults (ibo.org/about-the-ib). Our school serves children ages 3 to 16. More than 54 countries are represented, and 75 percent of our students come from outside of Denmark. I teach 20 third graders (8-year-olds) who come from all five continents and represent 14 countries.

For this project, I focused on my class and on Morgan, who was diagnosed with ADHD before joining ISB at the end of kindergarten. Children with ADHD have trouble self-regulating. They may demonstrate restless and/or impulsive behaviors and have difficulty paying attention (Brillante 2017, 109). During first and second grades, Morgan received one-on-one, in-class support. As he began third grade, he received support outside of the classroom, meaning he missed participating in the classroom community. As a school, we soon shifted to having a third teacher, who provided in-class support for Morgan and the other students in our classroom.

Inclusion is critical for learners with diverse abilities, strengths, and needs.

Besides myself, the adults involved in this inquiry included Morgan’s parents; my teacher research study group; a child psychologist, Bent Hougaard, who observed in the classroom; and my coteachers, Rasmus and later Sonia. Rasmus is an experienced teacher who worked in different countries before joining us in Denmark. She worked with this group of children in second grade, which was especially helpful at the beginning of the year: the children already had an established relationship with her, and she was aware of any learning and social issues. During this time, Rasmus was also conducting teacher research focused on inclusion. We found the interconnectedness between our two projects helpful, as they both had an impact on the progress made by Morgan and his peers. After the winter break, Sonia, a first-year teacher, joined us to provide further classroom support.

Data Collection

To gauge how play could create a more inclusive environment for Morgan, I decided to create independent tasks and projects that he would enjoy and that would connect him with his peers. Engaging in an iterative process, I documented these experiences, analyzed them with Rasmus and my teacher study group, then created new opportunities for Morgan and his classmates to build upon.

In order to collect my data, I used the following materials and techniques:

- Observations in and out of the classroom. At least twice a week, Rasmus and I took short videos and observed the classroom in relation to Morgan. While there were no set times for these, we always carried an iPad or sticky notes to record Morgan’s interactions. This helped us and the child psychologist to understand the dynamics of the group and Morgan’s reactions to specific situations. We were also able to gauge Morgan’s interactions with his peers and note any changes in his sense of belonging. I used the videos we took to look deeper into the way the children talked to each other. I sometimes showed them to the children, and I often took the recordings to my teacher research group to get their feedback.

- Interviews. We conducted four sets of formal interviews with Morgan throughout the school year to get his input about his engagements and his interactions. Rasmus and I developed a list of questions ahead of time. These were primarily open-ended so we could listen to Morgan’s ideas and sense of engagement and belonging. Interviews occurred during times that worked best for Morgan; both Rasmus and I were present with him.

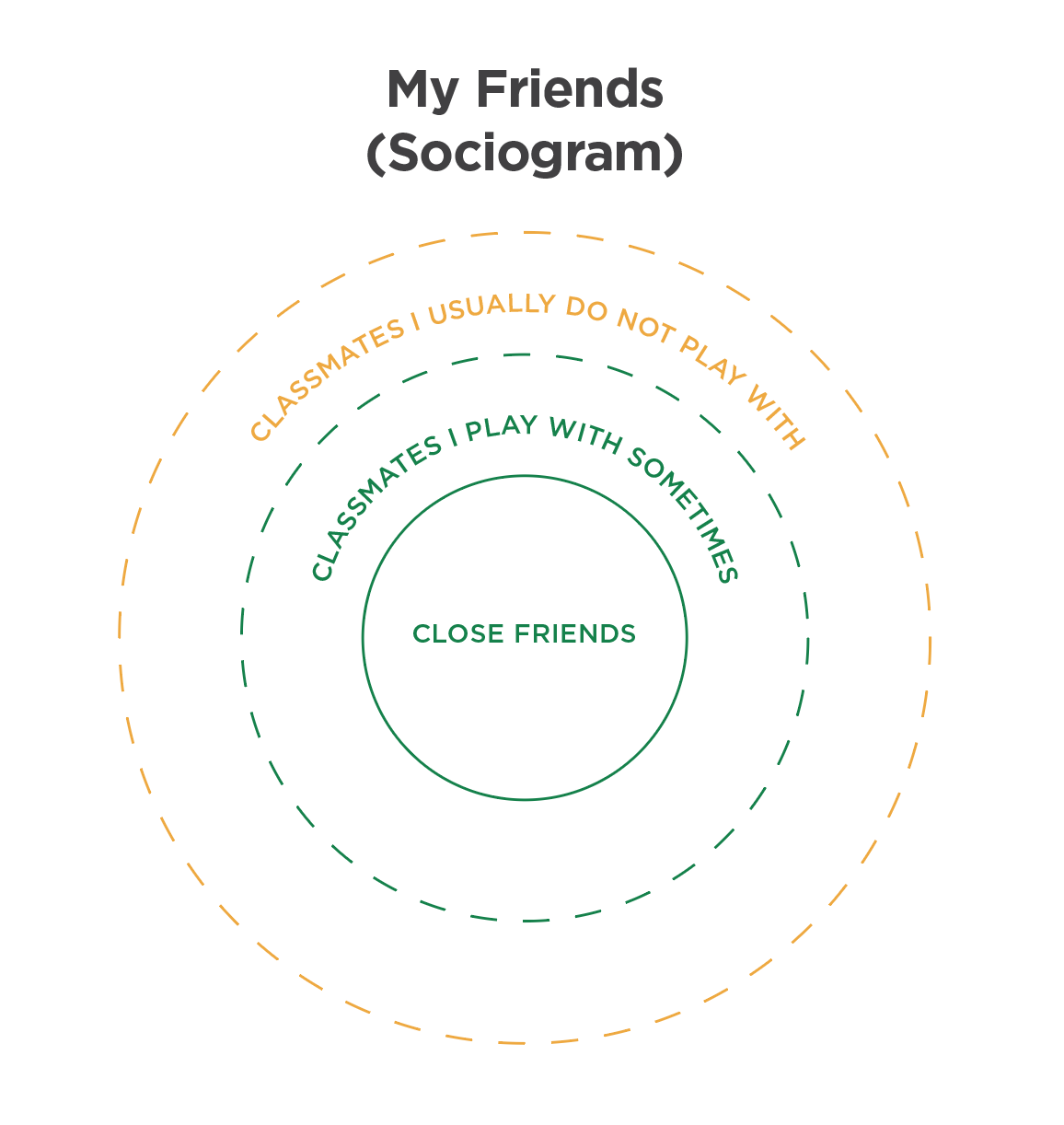

- Sociograms. We asked the whole class to fill out sociograms at the beginning of the year. This was intended to assess the number of relationships already formed among our students and to make sure everyone had a person close to them in class. Students revised these in February and in April, which helped us gauge the sense of community our class was developing.

- Conversations (narratives and notes). We filmed or transcribed conversations among our students inside the classroom and during breaks. We used these to reflect on our teaching, to plan next steps, and to understand the children’s relationships. Watching children and listening to the way they talk to each other or describe knowledge is a great tool for teachers.

- Children’s work samples. We took three to four photos of students each day. Besides showing their actual work, these photographs also included pictures of their wonderings and any “aha” moments they had as part of the learning process, along with connections to prior knowledge and specific interests.

Analysis

Rasmus and I met weekly for 30 to 45 minutes to look at and reflect on our documentation. Drawing on a technique from PPR, we began each of our meetings with a playful “replay” of something from our classroom interaction with the children in connection to inclusion. This replay took many forms: sometimes we would narrate a playful situation we observed; other times we would role play, write a song, draw a picture, or show a video from our class or our documentation. We would then take one piece of documentation and study it, using various protocols. To keep track of our notes, we created a shared, virtual document that we titled “Inclusion.”

We also took our documentation to our study group meetings, where group members examined it, then engaged in role playing to appreciate the children’s emotions and the ways they experienced different situations. This helped us as we discussed difficulties in moving toward inclusion and new steps that we could take to ensure that each and every child had a positive classroom experience. For example, during one of our first meetings, I explained that for the past three years, I had focused on supporting individual students’ efforts to build relationships. One of my colleagues, Kathy, said, “What about focusing on the whole class this year?” This is how I came up with more ideas about how to grow and maintain a supportive classroom environment.

Findings and Discussion

Through our data collection and analysis, we noticed new relationships developing among students. By drawing on and planning for Morgan’s strengths in a playful way, he became more settled, and the other children grew more keen to approach him. A discussion of our findings—tied to our three research questions—follows.

Belonging and Engagement

Research Question: How can I draw on and plan for Morgan’s strengths and interests to develop his sense of belonging and engagement in this classroom community?

As stated earlier, Morgan loved to create things out of loose parts and materials, draw, paint, and make books. We worked to build upon these interests to create special projects that would help him feel connected with his peers and the classroom.

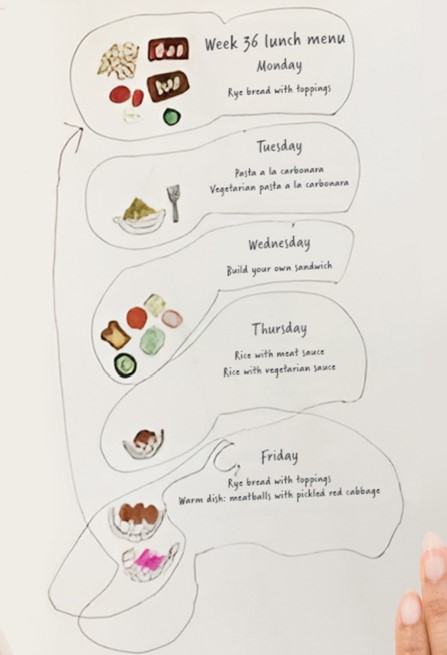

The first idea for an independent project came from Morgan’s mother. During one of our meetings, she shared that Morgan might enjoy drawing pictures next to items on the school lunch menu. Two days later I had this conversation with him:

Athina: Hey Morgan, what do you think about designing our lunch menu?

Morgan: Me?

Athina: Yes. You have awesome drawing skills so the leadership team suggested you could take on this task. This way, the younger students who don’t read yet can understand what we have for lunch each day.

Morgan: Oh yes! That makes sense! Sure, I will start now.

Athina: Thank you so much for helping out with this!

Every Monday, Morgan went to the canteen to display his illustrated menu.

One day, the kindergarten children were there when he arrived. They ran up to him and exclaimed over his pictures: “This is so cool”; “How are you so good at drawing?”; “Look, there is pasta this week!”

Morgan was so happy. He was able to see how helpful his menus were. During break time outside, I overheard him telling one of his classmates, “I am so happy the leadership team chose me to help the kindergartners with lunch. They cannot read yet; it is important.”

Inclusive teachers learn about children’s unique skills, talents, and passions and use that information to create engaging learning experiences.

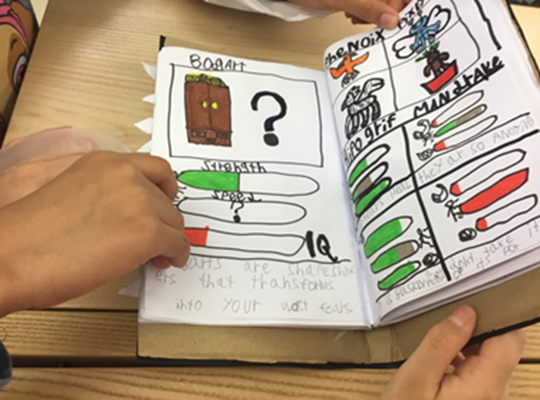

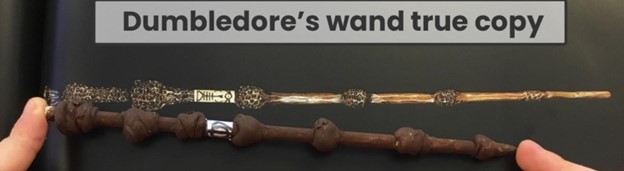

Our second project aimed to engage Morgan’s love of Harry Potter. He already had spent time creating artifacts from the movies, and with the help of Rasmus, he had written a book that our librarian displayed in the school library. Morgan made a second book nearly by himself, then a third and a fourth.

The librarian published all of them and put the books in circulation. Morgan was proud of his work, and there was much interest from our other students. Every day, someone would borrow a book and take it home to read, which made Morgan happy.

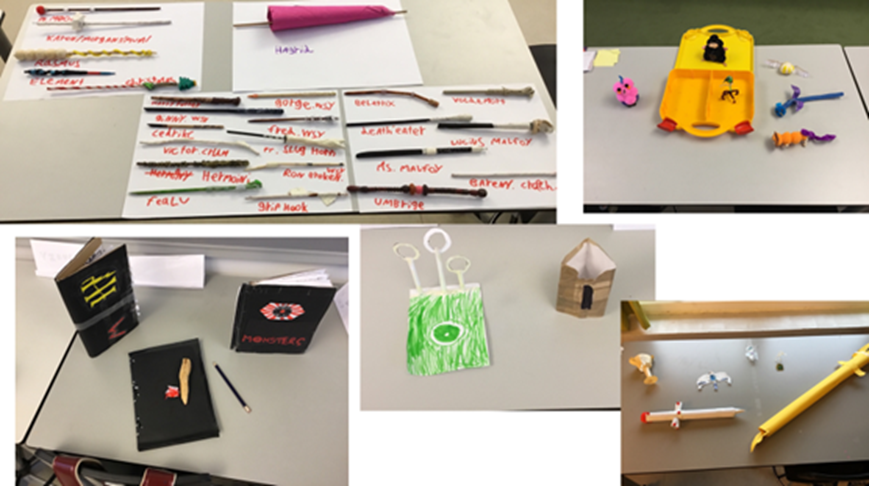

To honor this interest and highlight his strengths, we asked Morgan to make a classroom exhibit about Harry Potter:

Athina: I think this would be a great exhibition for everyone to see. What do you think?

Morgan: Like me making an exhibition for the class?

Athina: Yes! We could take time and set it up, and you could show all of these beautiful creations to your classmates. What do you think?

Morgan: Yes, I could do that, but I need to set up during break so people do not touch it and ruin it. I need two more days to finish . . . and then I can do it.

Athina: Super! I am so looking forward to it, and of course, we can help you set up.

Morgan spent a lot of time at home and school creating all of the Harry Potter wands and other materials based on the stories.

His classmates were amazed by his exhibition and had a great time talking about Harry Potter and how good Morgan was at crafting. After Harry Potter, Morgan created materials and new presentations about Pokémon and Avatar, which also engaged his classmates.

As we continued to give Morgan opportunities throughout the year to exercise his strengths and interests, we observed that he started going outside with his peers during breaks rather than staying in class with the teachers. After the winter break, he was asked to play by different children, and he created items that they could play with. During the weekly goal-setting meetings we had with him, Morgan was more accurate on what he needed to work on and was able to specify different strategies he would use to achieve his goal. This was an area of significant progress for him.

Learning Through Play

Research Question: How can a playful learning approach help?

As stated earlier, teachers at ISB strive to create playful learning experiences that promote choice, wonder, and delight. While Morgan did not always participate in our planned activities, he worked on content area skills in other ways during his play. For example, he practiced making graphs and representing data in various forms when he wrote his Harry Potter books. He experimented with size and diameter when he created different types of Pokémon balls. Because many of his projects incorporated writing, he became more aware of his writing and spelling; for example, he started using a dictionary, writing in lowercase, and incorporating punctuation.

Providing Morgan with playful experiences and allowing him to have his own space (with his crafting tools nearby) shifted his behavior. Because he felt more comfortable and settled, his interactions with others became more positive. Morgan said in our interviews that doing these projects made him feel proud and more confident. This was in contrast to the constant conflict we encountered when pushing Morgan to do the same tasks as the rest of the class. However, in our weekly documentation of attendance and participation, we observed that Morgan was also beginning to participate in classroom activities more often.

Establishing Relationships

Research Question: How will this playful approach influence Morgan’s relationships with others in the learning community?

During one of our study group meetings, a teacher researcher asked, “Do the other students ask to run their own projects?” This question really touched me; surprisingly, no other child in my classroom had asked to work on a project that was separate from what the rest of the class was doing. In addition, no one complained about Morgan’s independent activities. The reflection spurred by this question showed me how much the children understood Morgan’s situation—a sign that we were creating an inclusive classroom.

Rasmus and I saw big differences in Morgan as the year went on. The children appreciated Morgan’s creations, and new relationships developed. Carl, a child in our class who avoided Morgan at the start of the year, began playing with him during breaks. “Morgan is really creative,” he shared during a walk to our canteen. “He puts so much effort in his projects and stays so focused.” In February, when we asked children to fill out sociograms, I was delighted to see Morgan and Carl list each other in the “close circle of friends” space. This had never happened before.

Providing Morgan with playful experiences and allowing him to have his own space shifted his behavior.

Morgan’s peers—as Carl’s quote illustrates—started appreciating him for his strengths. Morgan began feeling more settled, and his creativity grew with his acceptance. He became less emotionally volatile, and he continued to explore his new relationships.

Reflections on the Research

Playful education and PPR helped me find ways to support Morgan in feeling settled and included. Of course, it was not always easy. In the beginning, we wasted a lot of time trying to convince Morgan to join in whatever the class was doing. Eventually, though, we understood his learning strengths, interests, and needs, and we let him choose when and how to do assignments. While we anticipate challenging behaviors from Morgan, we do not take it personally, and we do not hold on to that power. We calmly listen to his ideas, express what we would like to see, and ask what he needs help with.

I recognize that my Denmark setting affords flexibility that might not be possible in the United States or other countries. However, play is a powerful strategy for learning and for changing mindsets. So is engaging in teacher research. Both approaches helped me gain insights into children’s individual strengths, interests, and needs as well as how to plan, adapt, and improve my practice to create an effective, inclusive setting for each child. ISB has created a teacher toolbox that outlines ways to plan, manage, and reflect on playful learning environments (isbillund.com/academics/pedagogy-of-play). These tools, combined with playful teacher research, can open doors for creating community among all young learners, regardless of the setting.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- peruse an archive of Voices articles

- read the Fall 2022 Voices compilation

Photographs: header, 5, and 6 © Getty Images; 1–4 courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Agena, J., G. Boecker, & H. Churchill. 2021. “The Effects of Stigma on Students with Learning Disabilities and Inclusive Classroom Practices.” Reprinted from The Community Psychologist 54 (3). communitypsychology.com/effects-of-stigma-on-students-with-learning-disabilities.

Baker M., & G. Salas. 2018. “Inquiry Is Play: Playful Participatory Research.” Young Children 73 (5): 64–71.

Brillante, P. 2017. The Essentials: Supporting Young Children with Disabilities in the Classroom. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Catlett, C., & E.P. Soukakou. 2019. “Assessing Opportunities to Support Each Child: 12 Practices for Quality Inclusion.” Young Children 74 (3): 34–43.

DEC (Division for Early Childhood) & NAEYC. 2009. “Early Childhood Inclusion.” Joint position statement. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute; Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/ps_inclusion_dec_naeyc_ec.pdf.

Green, K.B., N.P. Terry, & P.A. Gallagher. 2014. “Progress in Language and Literacy Skills Among Children with Disabilities in Inclusive Early Reading First Classrooms.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 33 (4) 249–259.

HHS (US Department of Health and Human Services), & ED (US Department of Education). 2015. “Policy Statement on Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Early Childhood Programs.” Joint policy statement. Washington, DC: HHS & ED. https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/earlylearning/joint-statement-full-text.pdf.

IBO (International Baccalaureate Organization). 2016. “Challenging the Definition of ‘Play’.” The IB Community Blog, Jan. 22, 2016.

The LEGO Foundation. What We Mean by: Learning Through Play, June 2017, https://cms.learningthroughplay.com/media/vd5fiurk/what-we-mean-by-learning-through-play.pdf.

Meyer, L.E., & M.M. Ostrosky. 2013. “An Examination of Research on the Friendships of Young Children with Disabilities.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 34 (3): 186–196.

NAEYC. 2019. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

Nusche, D. et al. 2016. OECD Reviews of School Resources: Denmark 2016. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Odom, S.L., V. Buysse, & E. Soukakou. 2011. “Inclusion for Young Children with Disabilities: A Quarter Century of Research Perspectives.” Journal of Early Intervention 33 (4): 344–56.

Pedagogy of Play Research Team. “Playful Participatory Research: An Emerging Methodology for Developing a Pedagogy of Play” (working paper, Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA, 2016).

Sreckovic, M.A., T.R. Schultz, C.K. Kenney, & H. Able. 2018. “Building Community in the Inclusive Classroom: Setting the Stage for Success.” Young Children 73 (3): 75–81.

Walsh, G., D. McMillan, & C. McGuinness, eds. 2017. Playful Teaching and Learning. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publishing.

Welcome to the Danish Folkeskole. 2010. Undervisnings Ministriet. uvm.dk/publikationer/engelsksprogede/2010-welcome-to-the-danish-folkeskole.

Wells, M. 2014. “Predicting Preschool Teacher Retention and Turnover in Newly Hired Head Start Teachers across the First Half of the School Year.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 30: 152–59.

Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. n.d. “Inclusive Classroom Climate.” Accessed March 2023. https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/ClassClimates.

Zosh, J., E. Hopkins, H. Jensen, C. Liu, D. Neale, K. Hirsh-Pasek, L. Solis, & D. Whitebread. “The LEGO Foundation Learning Through Play: A Review of the Evidence.” 2017. White paper. https://cms.learningthroughplay.com/media/wmtlmbe0/learning-through-play_web.pdf.

Athina Ntoulia, MSc, is a homeroom teacher at the International School of Billund. Athina has worked with different primary year levels during the past seven years and has led Playful Participatory Research in collaboration with Project Zero. [email protected]