Public Libraries Harness the Power of Play

You are here

Sara, a librarian at a Texas library, closes The Seals on the Bus by Lenny Hort, a book she has just read with a group of 2- and 3-year-olds. Seated on the floor around her, the children each wear a name tag in the shape of a car. With their parents and caregivers nearby, the children sit calmly, listening to books about transportation and occasionally answering questions or making comments. In between books, Sara leads them in rhymes and songs about cars and buses.

This peaceful and relaxed scene soon changes: Sara pulls out rolls of masking tape, bowls of tiny plastic road signs, and bins of toy cars. The parents and children spring into action. At Sara’s suggestion, the adults construct roads on the carpet using the masking tape, and the children put up the signs and drive their cars. Within minutes, a tangle of roads crisscrosses the floor.

“Do you know what this means?” one mother asks, pointing to a yield sign. “It says yield, which means you let the other car go first.” She has her child wait while another child drives his car through. “Can you put the stop sign at the intersection?” a father asks. His child looks back at him. “The intersection is the place where the two roads meet,” he explains.

Other words pop up as the adults and children play: road, wheels, grocery store, traffic jam, crash, direction, stacked up. The parents and caregivers start their own conversations about intersections with traffic jams, the parking lot at the grocery store, monster trucks, remote-controlled cars, drained car batteries, and directions to various places. The children echo these conversations as they play: “Here comes a monster truck!” “Get out of the way, you’re about to crash!”

While it seems spontaneous and carefree, the din erupting in this library community room is actually a carefully planned strategy to strengthen parents’ (and other caregivers’) abilities to help their preschool children develop early language and literacy skills. Thanks to a nationwide parent education initiative called Every Child Ready to Read (ECRR), an increasing number of librarians are focusing on helping parents interact with their young children in meaningful ways to increase vocabulary development. These parent–child interactions in libraries involve activities in addition to reading books, such as the play session in the vignette. What looks like play, however, is actually an important part of helping parents—and other family members and caregivers—prepare their young children for later success in school. (It is important to note that while we often refer to parents and related terms like parent engagement, we believe in an inclusive concept of the parenting role. Many children are raised by adults other than their parents, including grandparents, other family members, fictive kin, etc.)

Why parent engagement?

The idea of fostering parent engagement is not new to public libraries. Family literacy has been a focus since at least the late 1980s, when a national movement emerged following the publication of “A Nation at Risk” (National Commission on Excellence in Education 1983). Since then, librarians in both formal programs and informal interactions have encouraged families to read and learn together.

Children learn more words when they have opportunities to respond to adults’ questions.

Every Child Ready to Read emerged with this movement. Developed in a joint effort by the Public Library Association and the Association for Library Service to Children, the program’s principles are seemingly simple: reading is an important life skill, learning to read starts at birth, and parents play instrumental roles as children’s first and best teachers. Librarians encourage parents to engage with their children using five practices crucial to literacy development: talking, singing, reading, writing, and playing. While these practices are already part of many families’ daily routines, ECRR librarians see their role as affirming that, and explaining why, parents are important to children’s literacy development.

The ECRR initiative, adopted in some capacity by nearly 50 percent of the 9,000 libraries throughout the United States, is rooted in a wealth of research showing that parent–child interactions are critical to children’s cognitive and social development, and are also a key predictor of later success in school (Neuman & Roskos 2007; Guttentag et al. 2014). The amount of speech parents direct toward infants influences the amount of language and vocabulary children develop (Weisleder & Fernald 2013). Many of the words children hear come during playful activities. The time parents and children spend singing, drawing, or playing games, for example, can positively impact a young child’s language growth and future literacy, since this time tends to increase vocabulary (Weigel, Martin, & Bennett 2006). Likewise, large motor activities that adults and children engage in together, such as jumping and marching, can aide in literacy development (Kirk et al. 2014). “By combining physical activity with lesson plans, teachers can work on both cognitive skills and physical activity, engaging children in ways that keep them active during the learning process” (Kirk, Fuchs, & Kirk 2013, 158). Games like Simon Says allow teachers to intentionally combine academic content, like new vocabulary or math concepts, with movement (2013).

Still, researchers caution that, for children to really learn vocabulary, the emphasis must be on the quality of the interactions, not just the quantity. Children learn more words when they have opportunities to talk, use novel words, and respond to adults’ questions. The key is conversation. Conversations are beneficial because they provide natural opportunities for adults to repeat the use of new words and give feedback to children (Wasik & Hindman 2015); they also engage children in trying to use new words, including placing them in the proper context. Reading together is a great way to spark conversations and introduce new words, making parent–child read-alouds particularly crucial in developing a rich vocabulary (Mol, Bus, & de Jong 2009). (For more details on the importance of reading to children from birth and throughout the early years, see the statement released by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2014.)

Given how crucial reading together is for language and literacy development, public libraries should have a major role in helping parents and children interact and play in meaningful ways to increase children’s vocabulary. Located in nearly every community in the country, libraries are open during the evening, on weekends, and throughout the summer to accommodate busy families. What’s more, their services are free. Filled with books and other resources, they offer print-rich environments full of novel words and experiences where families are increasingly coming to play, read, and learn together.

Investigating libraries

As part of a three-year study, the authors set out to determine how public libraries, particularly those that have embraced ECRR, are fostering parent engagement. From 2013–2016, we visited 36 library systems and 57 different branch libraries throughout the country. We selected 20 to serve as target libraries (10 were strong implementers of ECRR and 10 had not adopted the program at all), located in a variety of settings: urban (7), suburban (4), and rural (9). At each library, we collected the following data:

- Space observation: We examined each library’s physical space to see how environments were arranged to encourage parent–child interactions. We logged available play areas, toys, play objects, and computers; comfortable seating for parents and children; and activity stations where parents and children could interact. We also noted any type of sign, poster, or brochure that encouraged parents to interact with their children.

- Story-time observation: We observed the ways librarians used story-time programming to foster parent interaction and promote talking, singing, playing, reading, and writing. We noted if and to what extent free play, music, large muscle movement, and/or small motor activities were incorporated along with storybook reading.

- Programming analysis: We systematically documented the amount and types of programming offered during a typical month at each site, using library websites and calendars, and corroborating our findings by contacting librarians. We coded types of programs offered, such as programs for children from birth through age 5 or programs targeting STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), to better understand libraries’ priorities and approaches.

Our findings

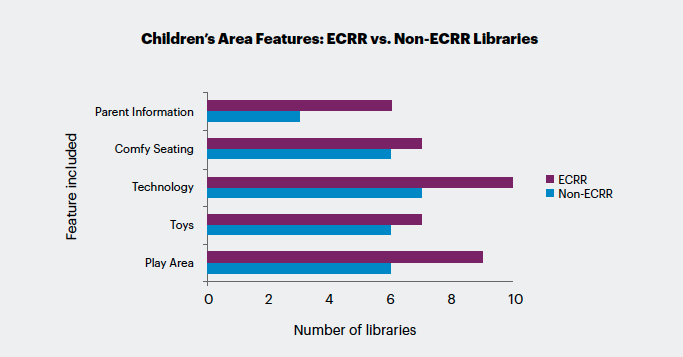

Our findings indicate that many libraries are providing wonderful opportunities for the children and families they serve. What initiatives such as ECRR are adding, however, is a strategic focus on the important role that parents have in their children’s education and literacy development. While many libraries are incorporating various elements of parent engagement, we found that the ECRR libraries are leading the way. For example, in our analysis of the libraries’ physical spaces, we found that the ECRR libraries were more likely to provide parent information about early literacy, areas with comfortable seating, technology, toys, and an area specifically devoted to play. (See “Children’s Area Features: ECRR vs. Non-ECRR Libraries.”)

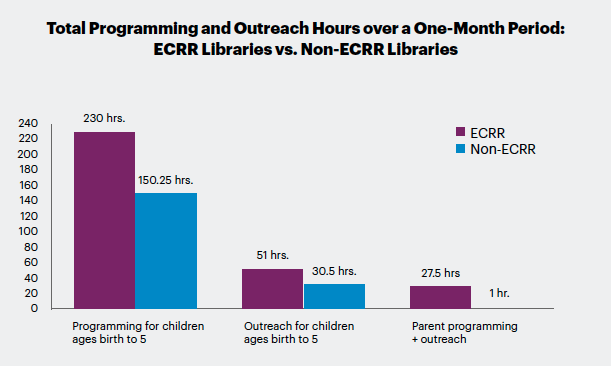

Our analysis of programming hours shows that all the libraries we visited are devoting a significant amount of time to programming for children birth through age 5, both in-library and off-site (e.g., doing outreach in community centers, schools, and parks). The ECRR libraries, however, are offering significantly more programs, thus providing more opportunities for parents and children to interact and play together. They also provide more parent-only workshops, designed to explain to parents the important role they play in their children’s early literacy and to show parents effective strategies for enriching their reading, play, and conversational time with their children. (See “Total Programming and Outreach Hours over a One-Month Period: ECRR Libraries vs. Non-ECRR Libraries ”.)

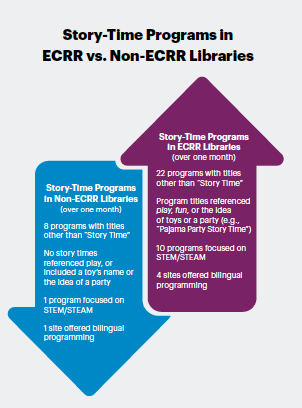

While ECRR libraries are scheduling more programs for young children than non-ECRR libraries, they also have made more substantial shifts in their programming, amending traditional story-time program names to include words such as play, fun, or party. Other shifts include combining play with STEM or STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, and math) content as well as offering opportunities for bilingual families to interact and play. (See “Story-Time Programs in ECRR vs. Non-ECRR Libraries.”)

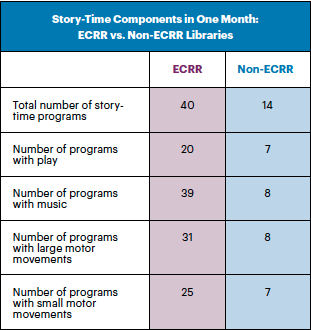

Finally, our story-time observations show that ECRR librarians offer many more opportunities for parents and children to interact with toys, games, and other activities during free-play segments. The ECRR libraries are also much more likely to include music and large- and small-motor movement—all contributing to a fun atmosphere that encourages parents and children to play together. (See “Story-Time Components in One Month: ECRR vs. Non-ECRR Libraries.”)

As these findings show, libraries can become community leaders in fostering parent engagement and young children’s school success. ECRR libraries have taken greater strides in this movement than those that have not implemented the program. Fortunately, our research demonstrates positive shifts in both library spaces and programming as libraries harness the power of play to insure school readiness.

Fostering parent–child interactions

Many libraries are remodeling their children’s areas to provide space for family interaction. This includes having a play area with toys, technology for children, and comfortable seating dedicated to caregiver–child interactions. As a result, the children’s areas in public libraries are often noisy, lively places where families learn from each other. In a Missouri suburb, for example, the ECRR library has become a destination for families in the community to play. The extensive children’s area features a play cabin called the Friendly Book Inn. There are stacks of large Legos, multiple plastic pieces of food and containers, three metal child-sized shopping carts, a handheld drawing board, and a wooden railroad set.

Targeting parents with early literacy information

Libraries are increasingly offering information—such as brochures, signs, and posters—about parents’ roles in early childhood literacy. This information helps reinforce the many fun ways that family time can be used to prepare children for school. For example, at the same Missouri library, a sign on a children’s table near puzzles and toys explains the value of play: “Playing is good for you! Play is the primary way that children learn. By playing freely, children can begin to understand larger concepts on their own. Take some time to play at the library today!”

Promoting play and fun

Libraries are changing traditional story-time programs to reflect the importance of play, especially with toddlers and preschool-age children. These include programs such as “Parachute Play for Toddlers,” “Play Baby Play!,” and “Music and Movement.” Other new titles allude to fun (“Fun for Ones”) and parties with toys (“Books, Blocks, and Tots”). Play at the library draws families in and helps them learn how early literacy develops, with a focus on developmentally appropriate activities for children of different ages.

Play is incorporated in various formats. In some programs, librarians bring out toys, balls, and games after the story portion of the program, encouraging families to stay and play together. At other times, the play portion is more elaborately designed to coordinate with the program’s theme. For example, an ECRR library in a rural New Mexico town offered a “One World; Many Stories” program for preschoolers. First, the librarians had children and parents listen to a storybook and then sing a song related to the theme. The librarian then explained the various play stations, each representing a different country or city. For China, parents helped children use tweezers (simulating chopsticks) to pick up colorful plastic elephants from one bowl and put them in another. For Rome, they played hopscotch in the middle of the floor, emulating a game Romans played with stones. Other play opportunities included multiple puzzles, a child-sized bowling set, magnets on a whiteboard, and an activity center where families could pour rice into empty plastic water bottles to create shakers.

Enriching interactions with STEM/STEAM

More library programming is incorporating STEM/STEAM, with offerings such as “Family Lego Night,” “Preschool STEAM,” and “Playdough Lab.” These enrichment activities offer children opportunities to hear novel words and explore new concepts in a play context, adding to their vocabulary and knowledge development. For example, a Texas library offers three story-time programs: “Color Science,” “Space Day,” and “Water Science.” In these programs, the librarian typically reads several books related to the theme and then children and parents complete an experiment. The “Water Science” program, for instance, features several tables with large tubs of water where children predict whether objects will sink or float.

Embracing bilingual families’ needs

Many libraries offer bilingual story times, with program titles such as “Amigos y Libros” and “Toddler Tales and Playtime: Spanish,” among others. Bilingual story times especially benefit dual language learners, who often start school with smaller English vocabularies than their English-only classmates. At a bilingual story time in an urban ECRR library in California, for example, a librarian led parents and children in songs and rhymes, first in English and then in Spanish, reminding parents of the benefits of speaking to their children in their home languages.

Providing more parent-only programming

Libraries are increasingly offering programming solely for parents (during which children are with library staff in a different room). In these sessions, librarians offer advice and suggestions on how parents and other primary caregivers can play with their children in ways that promote vocabulary development during their daily routines. At a suburban ECRR library in Maryland, for example, a librarian offered the following suggestions during a parent-only session: “Talk every day to your child—it could be at breakfast or in the car. Let him respond.” “Pretend play is important. When you are playing, pretend you and your child are the characters in the book.” “Ask, ‘What are you doing?’” “When you hear music at home, sing along with your child.” In these programs, parents often receive takeaway materials and suggested activities they can use to engage with their children at home.

Changing libraries

Our investigation shows that public libraries, particularly those participating in the Every Child Ready to Read program, are increasing their efforts to strategically focus their services on fostering parent engagement. As champions of family literacy, libraries offer programming, space, and resources that promote critical parent–child interactions through the everyday practice of playing together.

The trends we observed are perhaps a departure from what the public sees as typical library services. The emphasis on parents and children represents a substantial shift in how libraries have traditionally conducted business. The focus on playing, talking, and singing as well as on reading also signals that libraries are promoting a more expansive view than they have in the past of how literacy develops. (See “How Teachers Can Foster Parent Engagement with Libraries,” below.)

These changes are not without challenges. Public libraries constantly face funding shortages, which could prevent them from purchasing toys and other equipment to foster play. Some libraries do not have the physical space for an expanded play area; some librarians are better prepared than others to address parents or incorporate activities such as singing into their programming.

Our research has convinced us, though, that the movements spurred by programs such as Every Child Ready to Read are enduring shifts that will continue to grow. Although libraries’ emergence as leaders in school readiness is a relatively new role, we believe it is one that will substantially benefit the children, families, and communities they serve.

How Teachers Can Foster Parent Engagement with Libraries

- Many local library branches offer materials, such as brochures, activity sheets, or posters, that encourage parent engagement. Teachers can share these resources with children’s parents. In addition, teachers can encourage parents to attend events and programming at their local libraries.

- By working with school librarians, teachers can help develop a space in their school that encourages families to stay for a bit to explore books, toys, computers, and other interactive media. The space should entice families with comfortable seating, adequate lighting, and resources that both explain the importance of parent–child interactions and offer simple tips for enriching interactions. Bilingual families should be greeted with materials in their home languages and decorations or design elements featuring their cultures.

- Teachers can also plan events for children and their families designed around a particular theme or subject. In addition to reading books, the event should incorporate related play, music (including singing), and large motor activities, such as dancing or marching. Teachers can model storybook reading techniques and casually offer tips on the importance of parent–child interactions. Keeping the mood fun and playful will affirm for parents that their everyday practices of playing, singing, and talking are important to their children’s school success.

- With the help of the school librarian (or perhaps a local branch librarian), teachers can hold a parent-only workshop that explores parent engagement and its relationship to school readiness. Parents receive takeaway sheets with ideas for activities parents and children can do during routine chores like running errands, sorting and folding laundry, and bathing. Additional ideas might suggest how families can engage using interactive media, such as educational apps or e-books.

Resources

American Library Association Family Literacy Focus (www.ala.org/advocacy/literacy/earlyliteracy/famlitfocus)

This website provides more information about public libraries’ focus on family literacy and highlights several library initiatives that inspire families in ethnically diverse communities to read and learn together.

Every Child Ready to Read (www.everychildreadytoread.org)

At this website, readers can find additional information about the ECRR initiative. The ECRR toolkit (available for $200) provides youth librarians, early childhood specialists, and preschool teachers with resources to present workshops demonstrating how parents and caregivers can engage in talking, singing, reading, writing, and playing to develop children’s language and prereading skills.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. 2014. “Literacy Promotion: An Essential Component of Primary Care Pedriatric Practice.” Policy statement. Pediatrics 134 (2): 404–09. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/06/1....

Guttentag, C.L., S.H. Landry, J.M. Williams, K.M. Baggett, C.W. Noria, J.G. Borkowski, P.R. Swank, J.R. Farris, A. Crawford, R.G. Lanzi, J.J. Carta, S.F. Warren, & S.L. Ramey. 2014. “‘My Baby and Me’: Effects of an Early, Comprehensive Parenting Intervention on At-Risk Mothers and Their Children.” Developmental Psychology 50 (5): 1482–96.

Kirk, S.M., C.R. Vizcarra, E.C. Looney, & E.P. Kirk. 2014. “Using Physical Activity to Teach Academic Content: A Study of the Effects on Literacy in Head Start Preschoolers.” Early Childhood Education Journal 42 (3): 181–89.

Kirk, S.M., W. Fuchs, & E.P. Kirk. 2013. “Improving Preschool Literacy Skills using Physical Activity.” Research to Practice Summary. Dialog 16 (3): 155–59. https://journals.uncc.edu/dialog/article/viewFile/66/178.

Mol, S.E., A.G. Bus, & M.T. de Jong. 2009. “Interactive Book Reading in Early Education: A Tool to Stimulate Print Knowledge as Well as Oral Language.” Review of Educational Research 79 (2): 979–1007.

National Commission on Excellence in Education. 1983. “A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform.” A Report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education United States Department of Education. https://bit.ly/1BpI7OU.

Neuman, S.B., & K. Roskos. 2007. Nurturing Knowledge: Building a Foundation for School Success by Linking Early Literacy to Math, Science, Art, and Social Studies. New York: Scholastic.

Wasik, B.A., & A.H. Hindman. 2015. “Talk Alone Won’t Close the 30-Million Word Gap.” Phi Delta Kappan 96 (6): 50–54.

Weigel, D.J., S.S. Martin, & K.K. Bennett. 2006. “Contributions of the Home Literacy Environment to Preschool-Aged Children’s Emerging Literacy and Language Skills.” Early Child Development and Care 176 (3-4): 357–78.

Weisleder, A., & A. Fernald. 2013. “Talking to Children Matters: Early Language Experience Strengthens Processing and Builds Vocabulary.” Psychological Science 24 (11): 2143–52.

Photographs: © courtesy of the authors

Donna C. Celano, PhD, is an assistant professor of communications at La Salle University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She served as a senior researcher on the national evaluation of the Every Child Ready to Read initiative. Her research interests include family literacy and children’s access to and use of books, computers, and other media. [email protected]

Jillian J. Knapczyk, MA, is a research coordinator at the Literacy, Technology, and Culture Lab in New York City. She has worked on statewide and national studies of access to literacy in under-resourced areas. [email protected]

Susan B. Neuman, EdD., is a professor of childhood education and literacy development in the Teaching and Learning Department at New York University. Susan specializes in early lieracy and oral language development, and focuses her work on interventions that change the odds for children from low-income families. [email protected]