Learning to Listen: Supporting Dual Language Learners’ Language Acquisition and Learning Identities (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Mary Jane Moran, Voices Executive Editor

Through her yearlong action research study in a first grade classroom, Laura Latta learned much more than how to guide dual language learners’ efforts to learn to read and write. As she changed her practice, Laura began to hear the children’s expressed needs and contributions to their own learning. She learned to listen. For Laura, this meant giving up some control as the decisionmaker while acknowledging the children’s ideas and their rights to describe and define the learning experiences that were most useful to them. This classroom research is about a teacher who embarked on a pedagogical journey and ended up engaged in coinquiry with her students. In teacher research, such a shift is common.

When teachers set out to study their practice and devote attention to the ways their practice affects children’s learning, it establishes a new dynamic, one that focuses on the relationship between teachers’ and students’ learning. Teachers who document, reflect, and make changes to their practice create a kind of classroom workshop for their own professional development. This outcome is one reason teacher research helps sustain us as teachers as we continually reconsider our practice in relation to our students’ learning.

This article is both a story and an invitation. The story reveals how one teacher learned alongside her students and changed as a result. It also shows how young children were given the space, time, and opportunity to take charge of their learning and, in so doing, developed literacy skills and confidence as learners. The invitation is to you, the reader, to take up a question that matters to you and the children in your classroom and to begin to listen through your documentation, reflection, and actions to what you hear, see, and wonder about. As Laura reminds us, when we listen to the children in our classrooms, we discover that they have many things to teach us.

As a monolingual early childhood educator working in a diverse public school in the Midwest, I am constantly in search of strategies for supporting my young learners. A majority of the children in my classroom (14 out of 24) are dual language learners (DLLs); as they learn English at school and their home languages (Spanish [12], Vietnamese [1], and Hmong [1]) with their families, they are on a path to becoming bilingual. Admittedly, there are moments when I feel humbled and intimidated by the task of supporting these children effectively as they grow and learn.

When I accepted this position—teaching a kindergarten/first grade loop in a Title I public elementary school where two-thirds of the children speak Spanish—I felt that it was important to understand second language development. To strengthen my teaching approaches, I began grasping at every piece of research I could find related to dual language instruction. As I immersed myself in the literature about dual language acquisition and effective instructional strategies, I realized there was a limited amount of research that included the firsthand perspectives of DLLs as they reflected on their own language acquisition process. I began to conduct a pilot study focused on gaining a more comprehensive understanding of how the children in my classroom were acquiring language and how I could most effectively support them in this process. It was important to me to consider the lived experiences of DLLs in my study. I decided to take a qualitative approach, beginning with interviewing two of my colleagues.

Insights from colleagues

Two of my teaching colleagues, Taty and Jenny, had experienced firsthand what it was like to immigrate to the US as preschool-age children. Both were willing to share their experiences with me over the course of three individual interview sessions each.

Taty migrated with her family to California from San Juan, Puerto Rico, just before entering kindergarten. Her first school experiences were largely negative. She felt alone, scared, and intimidated. The culture (specifically food, language, and clothing) felt so different from her experiences in Puerto Rico that it made her transition very difficult and uncomfortable.

Taty went to kindergarten knowing Spanish and very little English; she felt excluded from the group. She explained that not knowing what others were saying “put her in a really dark place.” In order to see the “light at the end of the tunnel,” she knew that she had to speak English. However, this felt risky— she was not willing to experience embarrassment by making mistakes in front of her peers. Over time, she began to feel comfortable in the classroom as her teacher listened to her, had patience with her, and was willing to meet her linguistic needs.

Like Taty, Jenny immigrated to the US with her Cantonese family just before she started kindergarten. When Jenny reflected on her first experiences as a DLL, she described herself as fearless. She was ready to “do school” because the importance of school was emphasized in her home. However, once she realized that her kindergarten peers did not share her language or culture, she became hesitant and self-conscious about communicating with others.

Jenny went through a silent period during which she spoke very little Cantonese or English; this silence lasted from kindergarten through second grade. Jenny reminisced, “It was my second-grade teacher who recognized that I was not doing well at anything [in school], so every day she started working with me just a little bit. It was just oneon- one with me—simple words and stuff. She also sent me to a reading specialist, and I worked daily in a small group. Every day she would work to support me.”

Interviewing my two colleagues gave me key insights into the direction of my research. Both Taty and Jenny credit their supportive teachers with playing important roles in their decisions to become teachers of DLLs. I recognized that the process of language acquisition is deeply relational, requiring the development of trust between child and teacher. Additionally, one of the most powerful qualities of both Taty’s and Jenny’s teachers was that they took the time to listen to the children and met them where they were. This reminded me about the concept of competent listening: “Learning how to listen is a difficult undertaking; you have to open yourself to others. . . . Competent listening creates a deep opening and predisposition toward change” (Rinaldi 2006, 130).

Documenting my reflections on the interviews in my field notebook, I wrote, “Listening to my children and letting their voices guide my instruction is where I should begin my work.” And so I began my journey with a step back from my usual ways of teaching, replacing “listening-as-usual” (Davies 2014, 34) with a more deliberate, engaged positioning that gave room to my students to help chart the course of their own learning.

Review of the literature

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory served as the foundation for my study. Vygotsky (1978) stated that as children develop language (both first and additional languages), they use private speech to organize their actions. Private speech is self-directed and supports thinking; it is a precursor to the voice inside the mind (inner speech) that develops later in childhood. During play, a child might describe aloud what he is doing, even when he is playing alone. For DLLs, participating in both play and private speech aids in developing knowledge of social and experiential vocabulary.

I observed this phenomenon as two of my DLL students, Alison and Sophia, played dress up with figurines. Alison, speaking aloud to herself, quietly labeled the parts of her doll’s outfit in Spanish: collar, falda, and zapatos. Overhearing Alison, Sophia pointed to each of the items, stated the English words—necklace, skirt, and shoes— and then refocused her attention on her own doll.

Applying Vygotsky’s (1978) lens, it seems that Sophia, Alison’s trusted friend, was operating as a more knowledgeable other, listening in and then building Alison’s understanding of the English versions of the Spanish labels she used to describe the doll’s clothing. Vygotsky noted that for learning and development to occur, a more knowledgeable person—like Sophia—should engage with the learner in her zone of proximal development (the area of dissonance between what a child knows and can do on her own and what she still needs guidance from another to do). Mentors and more knowledgeable peers guide participation in the learning process through scaffolding (Wood, Bruner, & Ross 1976; Rogoff 1993). As this shared participation unfolds among DLLs, children develop new understandings and gain access to words that can be used to describe their everyday experiences.

Language acquisition

One helpful model of second language acquisition sets forth five progressive stages: preproduction, early production, speech emergence, intermediate fluency, and advanced fluency (Krashen & Terrell 1983). Children move at their own pace, largely depending on the support they receive in their first and second languages and the availability of contextualized instruction (Lake & Pappamihiel 2003; Buyse et al. 2014).

Contextualized instruction includes using visuals when teaching new vocabulary, providing hands-on learning activities, designing a print-rich environment (with an assortment of engaging texts and labels), singing songs, acting out finger plays, fostering peer support through play, role-playing, and using gestures to accompany speech.

Deepening my knowledge of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, second language acquisition, and competent listening helped guide me toward the realization that I should invest time building relationships with each of my students individually. My instruction should be child centered, tailored to each child’s expressed or observed needs. To do this effectively, I had to create opportunities to form trust-filled relationships. I also had to build time into the schedule to observe the children, to ask them to share their thoughts about their learning, to listen intently to their responses, and to provide supports based on their feedback.

Methodology

For this yearlong action research study, I worked closely with a small group of eight DLLs in my first-grade classroom who speak Spanish at home. On an English language assessment, each of these children qualified as emergent DLLs. My research was guided by the following question: How could I most effectively support the language development of emergent dual language learners in my classroom?

Setting

I teach in a community school, a traditional public school that has been expanded to include a medical clinic and other amenities to make it a community hub. Family engagement is considered a top priority by the administration and teaching staff and is reflected in the school’s vision statement. Before the start of each school year, my colleagues and I conduct home visits to get to know children and their families in a comfortable setting. Additionally, teachers are able to establish close connections with the children and their families as they teach in two-year looping cycles. The children in this study were in first grade, the second year of their loop with me as their teacher.

Procedures

Throughout the study, I met with eight focus children—Andrew, Aaliyah, Niko, Alison, Alexa, Edgar, Sebastian, and Sophia (their self-selected pseudonyms)—at least three times a week, either individually or in small groups of two or three. At the beginning of the school year, these meetings were instructional mini-sessions during which I taught vocabulary, reading strategies, or foundational reading skills (such as letters, sounds, and sight words). During this time, I saw myself primarily as an interventionist, teaching what was needed to help the children learn. However, I quickly realized that this role was not highly effective; the children quickly grew disengaged when not given a voice in their own learning processes.

Feeling somewhat disappointed that my approaches were not as fruitful as I had hoped, I went back to the literature. The concept of pedagogy of listening resonated strongly with me (Rinaldi 2006). Listening requires openness, sensitivity, suspension of judgment and assumption, willingness to change, and flexibility. As a listener, “the teacher is not removed from her role as an adult, but instead revises it to become a cocreator, rather than merely a transmitter, of knowledge and culture” (Rinaldi 2006, 141). I realized that truly listening to the children was far more complex than I initially thought. In order to develop my own pedagogy of listening, I would have to approach my teaching encounters as more than an interventionist. I decided to adopt a more inquisitive instructional approach, observing the children and listening to their needs and preferences as learners.

Transformation of teaching roles

My instructional roles evolved throughout the school year because of my research. As the year progressed, my pedagogy as a competent listener developed (Rinaldi 2006), and I added new layers to my identity as a teacher. I felt myself becoming more flexible and multidimensional in my practices. Additionally, the way I thought about teaching and the questions I asked myself about the children changed; I focused less on my role as a teacher and more on the students’ roles as capable constructors of knowledge.

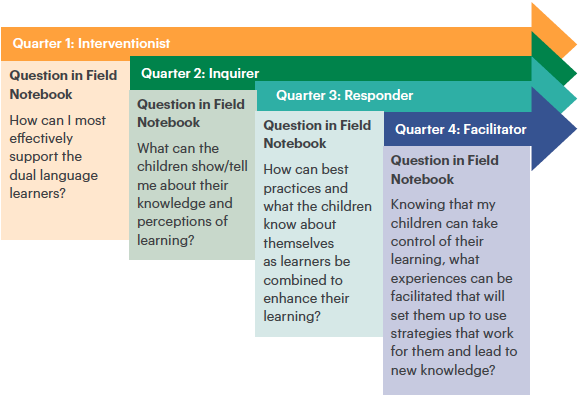

During the first quarter of the school year, I confidently approached my work as an interventionist, armed with research and ready to implement all of the effective instructional strategies I found in the literature. However, I quickly realized that even though I knew a lot about child development and language acquisition, I needed to do more than just provide instruction. I had to consider each child’s specific perspectives, preferences, and abilities. During the second quarter, I began to understand what it really meant to listen to the children. My role shifted to that of an inquirer as I set aside time to pause and regularly interview the eight DLLs in my study to see how they felt their learning was going, what was working best for them, and what they enjoyed most. During the third quarter, my ability to engage in competent listening deepened, and my role expanded to include being a responder. I was then able to pair my knowledge of pedagogy with the children’s responses to generate more meaningful child-centered activities and lessons. By the fourth quarter, I embraced opportunities to be a facilitator, helping the children create learning resources for themselves that made them feel most successful.

Instructional supports

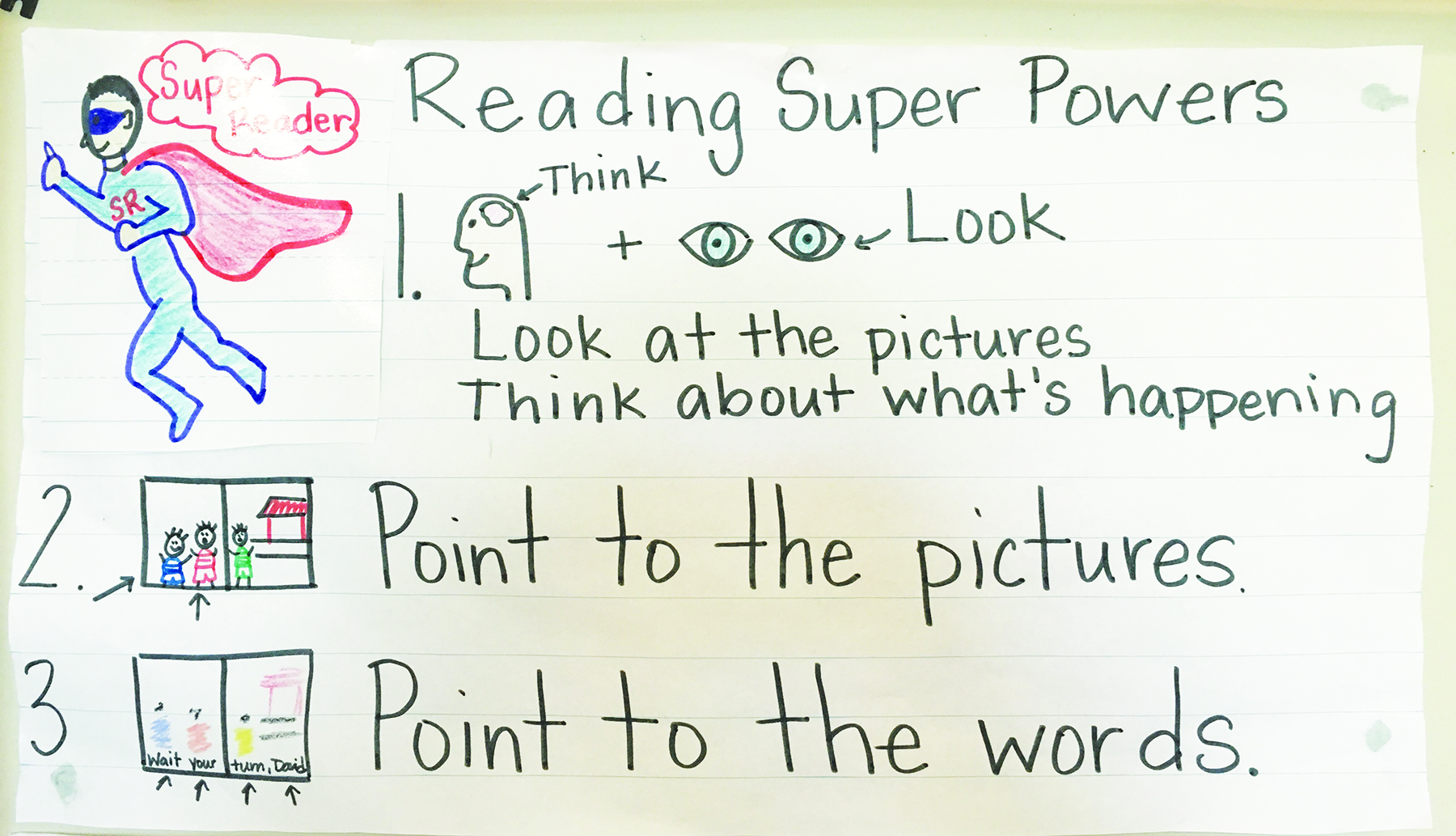

When I interviewed the children about their learning, many of them referred to specific cues posted in the classroom that they used as learning tools. One day, after the children settled into their reading spots, I noticed that Niko had positioned himself on the floor right next to our “Reading Super Powers” anchor chart (inspired by Calkins et al. 2015). He kept glancing up at the anchor chart and then pointing to his book. I sat down next to Niko, quietly watching as he pointed and looked. Eventually, I asked him what he was doing. He explained that he was practicing his pointing as he read his book:

“Point to the pictures. Point to the words. This [anchor chart] helps me remember.” Niko was using the visual reference to remind himself of a strategy that I had taught in a whole group lesson a few weeks before. I had developed this chart in advance, used it during the lesson, and then placed it where the children could easily refer to it.

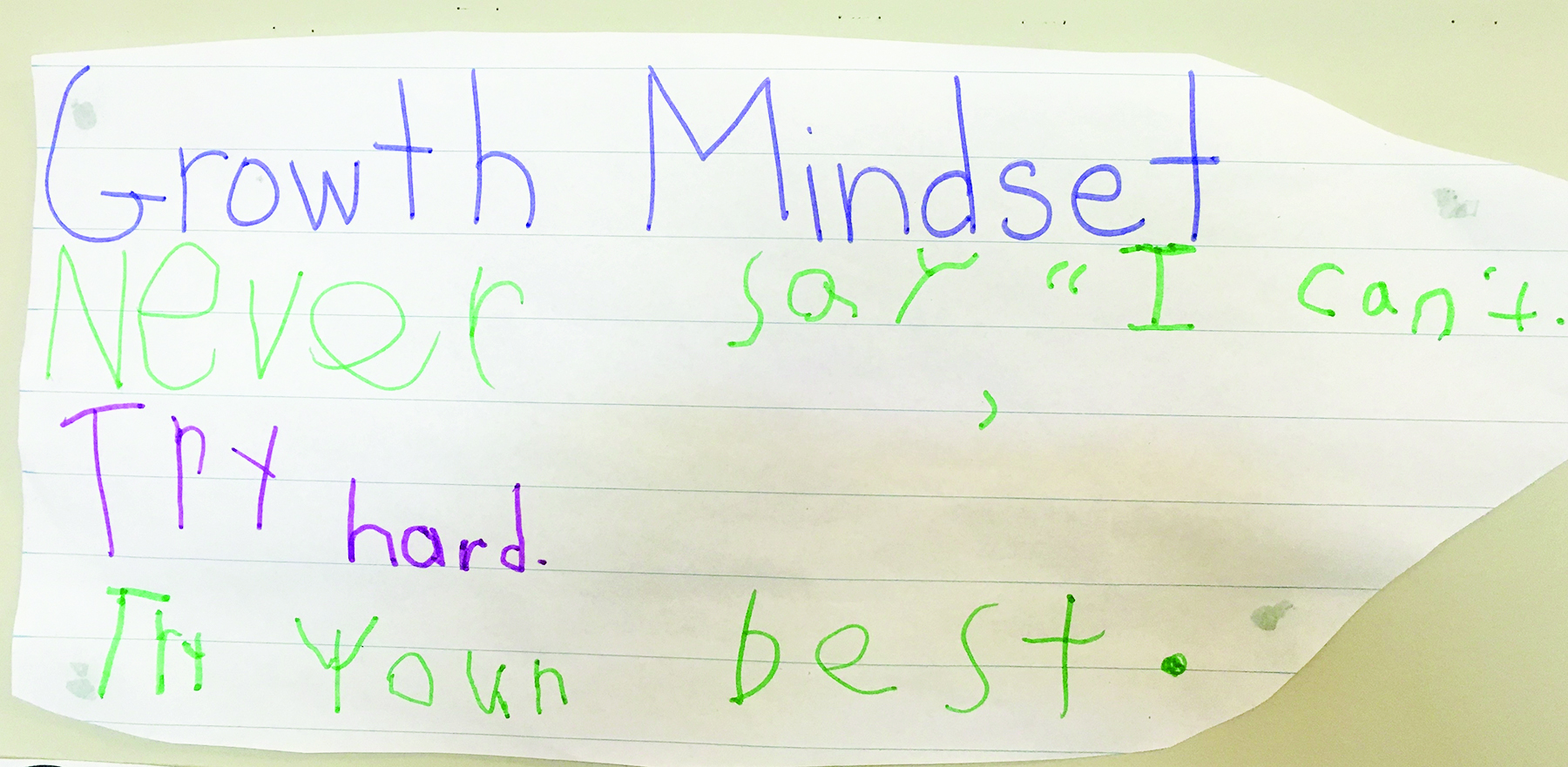

While I created some charts ahead of time, many charts were cocreated with the children during community circle or small group time. The children helped make decisions about what sorts of pictures and words would be displayed on the charts and where we would hang them in our classroom. As we discussed ideas to support us as learners, such as having a growth mindset (Dweck 2015), I encouraged the children to add their own writing to the charts.

In addition to the charts, the children mentioned during interviews that they used the following cues to help themselves in reading, writing, and math: the word wall, their individual lists of high-frequency words, a number line, their memories of our class read alouds, the alphabet, number grids, and flash cards.

It was interesting to note how the children described their use of anchor charts and other cues. Andrew mentioned that he used anchor charts to remind him “how to do things like stretch out the words” as a strategy for decoding challenging words. Niko stated that he used the number line to remind him of numbers he did not know how to write. Sebastian referred to anchor charts and books read aloud in class to give him ideas for writing stories. Alison used the word wall to jog her memory about how to read and write frequently used words.

Social supports

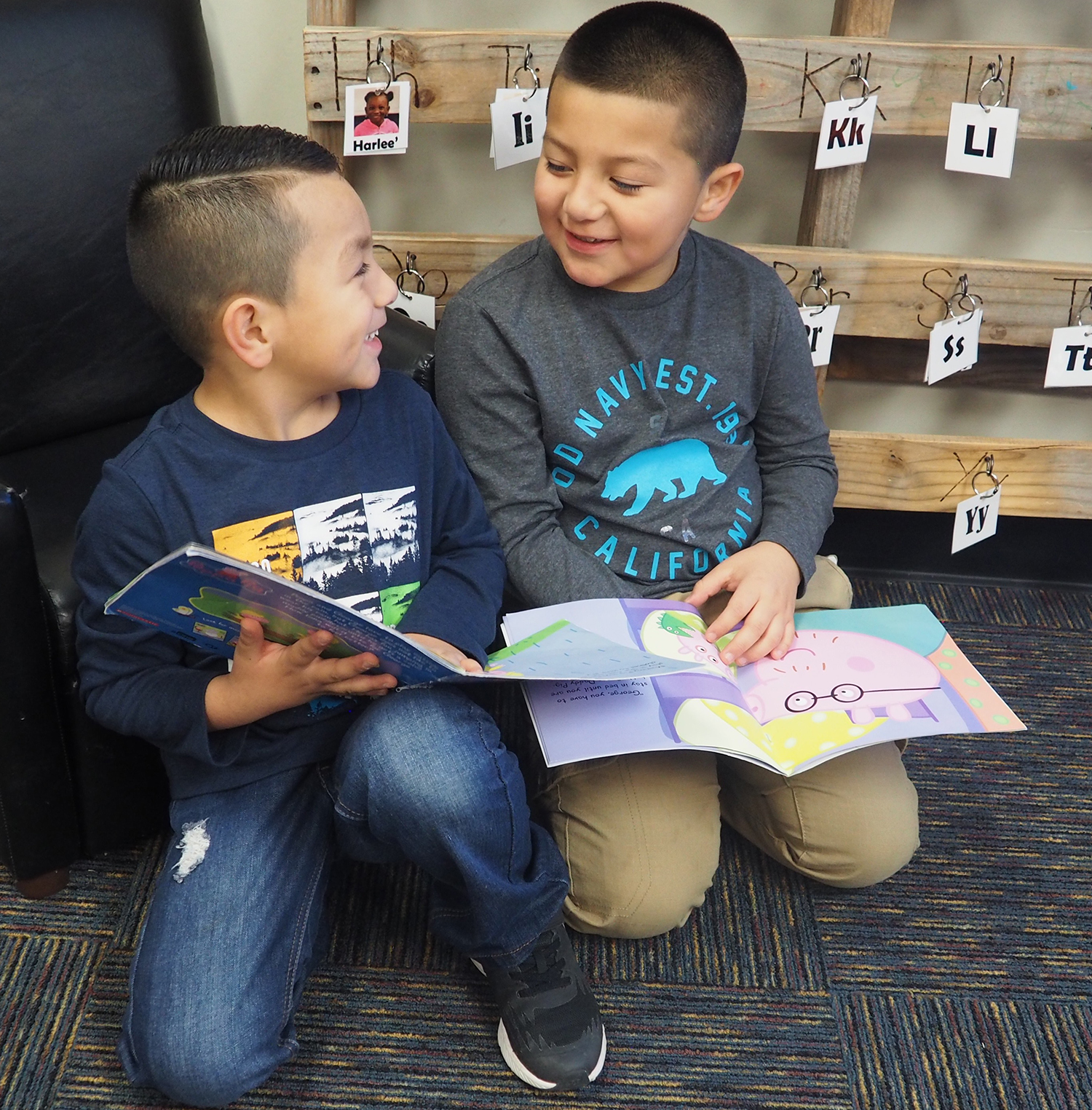

Another important finding regarding the children’s perceptions of learning was the social quality of the learning experiences. Each of the children recognized several individuals who supported them in their learning, many of whom were classmates. When asked about the people that helped him in his learning, Edgar replied by listing off the names of five of his friends; then he added, “If I forget [how to do something], I just ask somebody to help me.” Additionally, the children eagerly chose classmate reading partners to practice reading aloud with daily. After the children practiced in pairs, I was amazed when they began asking me if they could assume the role of the teacher and read to the entire class, showing off their new reading skills. The children cheered for one another when their classmates read aloud. Highlighting these new reading skills became a regular occurrence in our class during reading time each day. The children also mentioned family members who spoke with them and read to them in English or Spanish. Edgar stated, “My dad, he sits next to me. He shows me [how] to read.” Family members, classmates, and teachers all served as more knowledgeable others who scaffolded the children’s learning (Vygotsky 1978).

Responsive teaching, internalized learning

Through our standing weekly check-ins, the children realized that I valued their insights. I listened closely and used their feedback to incorporate more of the instructional supports that they found enjoyable, engaging, and helpful. In interviews, it was clear that all eight children participated in the process of building their identities as readers, writers, and mathematicians. Having been granted autonomy, choice, and voice in this process, the children were highly motivated to continue developing their identities as learners (Reeve 2006). As I met with the children during the course of the year, I observed an increase in their confidence and in their openness to sharing their learning preferences with me. Alison explained to me that she liked to “show me how to read” and added, “I am good at reading.” The children took control of their learning because they felt joy in the process, experienced competence in their identities as learners, and felt amply supported by their teacher and peers.

Overall, analyzing data over the course of the study yielded some important findings:

- When I became more aware of the children’s abilities to develop their identities as learners, my identity as a teacher also developed. Initially, I perceived myself as an interventionist until I realized the importance of adding the new layers of inquirer, responder, and facilitator to my identity as an educator.

- As I changed my teaching strategies to make more time to listen and to include approaches that the children found to be supportive (one-on- one instruction, peer learning time, and increased anchor charts and cues), the children not only demonstrated increased academic progress, but also became more expressive and articulate about their learning preferences and identities as learners.

- Every child referred to specific social supports (friends, family members, and teachers) as helpers in their language-learning process. Children enjoy learning with their friends and family members. By encouraging these social supports to emerge and develop, I was able to foster a culture of learning in the classroom and help the children see new opportunities for learning with family members at home.

- The children internalized the strategies depicted on the charts in the classroom, especially when they cocreated the charts. With time, Niko, for example, no longer needed the “Super Reading Powers” chart to remember the strategy of pointing to pictures and words as he read. Similarly, Sebastian found that he used the chart on solving math problems so much that he could “add in [his] brain now.” Eventually not only were all of the DLLs in my study able to pull the strategies from memory, but they also knew the appropriate situations in which to apply the strategies.

Lessons learned

Language acquisition is a complex process and is experienced differently by every learner. All children bring to the classroom unique sets of cultural backgrounds that shape the way they feel about their school environment, learning, and interactions with their peers. Spending time thinking about Taty’s and Jenny’s experiences made it clear to me that setting aside individualized time and space dedicated to each of my DLLs is a critical aspect of supporting their learning.

At first, these weekly touchpoints fell flat as I attempted to teach at the children instead of learning from and with them. Once I realized this, I approached the check-ins without preconceptions and asked the children to share what they enjoyed most about learning. I then incorporated more of those things (i.e., cocreated anchor charts, cues, and social experiences) in my daily instruction. With each meeting, my students took increased ownership of their learning and realized that their voices were powerful in shaping their learning process.

My new understanding about children’s capabilities to communicate their needs, preferences, and identities changed the way I approach my instruction with all of my students, especially my DLLs. When given the opportunity to talk about how they constructed knowledge, the children were eager to share the strategies they liked and found most helpful. However, I had to approach these conversations as a competent listener. This meant avoiding preconceived ideas about what the children might tell me. I endeavored to “suspend my judgment and prejudices” to make room for the children to share their most successful moments of learning (Rinaldi 2006, 81). My learners challenged me to be flexible and responsive.

They showed me that building a learning environment inclusive of all learners requires me to pay close attention to their needs and facilitate experiences in which they can claim their own learning. My first-graders helped me realize the importance of listening fully and intentionally in order to seek vital information about who they are and what they need as learners, for they are quite capable of giving it.

References

Buyse, V., E. Peisner-Feinberg, M. Paez, C.S. Hammer, & M. Knowles. 2014. “Effects of Early Education Programs and Practices on the Development and Learning of Dual Language Learners: A Review of the Literature.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29 (4): 765–85.

Calkins, L., N. Louis, A. Hartman, E. Franco, K. Wears, R. Cronin, A. Baez, M. Martinelli, C. Holley, & E. Moore. 2015. Units of Study for Teaching Reading, Grade K. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Davies, B. 2014. Listening to Children: Being and Becoming. Contesting Early Childhood series. New York: Routledge.

Dweck, C. 2015. “Carol Dweck Revisits the ‘Growth Mindset.’” Education Week. Editorial Projects in Education. www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/09/23/carol-dweck-revisits-the-growth-mi....

Krashen, S.D., & T.D. Terrell. 1983. The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom. Hayward, CA: Alemany Press.

Lake, V.E., & N.E. Pappamihiel. 2003. “Effective Practices and Principles to Support English Language Learners in the Early Childhood Classroom.” Childhood Education 79 (4): 200–03.

Reeve, J. 2006. “Teachers as Facilitators: What Autonomy-Supportive Teachers Do and Why Their Students Benefit.” The Elementary School Journal 106 (3): 225–36.

Rinaldi, C., ed. 2006. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning. Contesting Early Childhood series. New York: Routledge.

Rogoff, B. 1993. “Children’s Guided Participation and Participatory Appropriation in Sociocultural Activity.” In Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in Specific Environments, eds. R.H. Wozniak & K.W. Fischer, 121–53. The Jean Piaget Symposium series. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Eds. M. Cole, V. John- Steiner, & E. Souberman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D.J., J.S. Bruner, & G. Ross. 1976. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology 17: 89–100.

Photographs: © Courtesy of the author

Laura Latta, MEd, was the 2015–2016 Union Public Schools District Teacher of the Year. She currently works as a community school coordinator, teaches at the University of Oklahoma, where she is a doctoral candidate, and is a graduate research assistant for the Early Childhood Education Institute at OU–Tulsa. [email protected]