Spreading Happiness: A Preschool Classroom in Washington, DC, Investigates Citizenship and Makes a Statement—“Be Happy!” (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the article | Ben Mardell, Voices Executive Editor

In her essay “What is Education For?” classicist and political scientist Danielle Allen (2016) offers a compelling case that education’s contribution to equity is not, as many assume, vocational training but through promoting civic agency. By this measure, teacher Georgina Ardalan’s Title One preschool classroom in a Washington, DC, public school does a great deal to promote social justice. In her article, Ardalan explains how, by using documentation to listen closely to children, she facilitates a long-term project that expands their literacy skills and their ability to discuss, debate, and think critically. As a teacher researcher, Ardalan explores ideas, enlists colleagues to help her think more broadly, and envisions new possibilities for her community while offering her students opportunities to do the same. This is more than coincidence; taking up the mantle of teacher researcher is one way to promote social justice. For additional commentary, see “Parallel Voices Commentary: Spreading the Happiness: By Seeing Children as Citizens, a Teacher Helps Them Be Big” by Ben Mardell at the end of the article.

In winter 2016, I began a long-term project to engage the 16 three-year-olds in my Title I Head Start class at J.O. Wilson Elementary School, in the District of Columbia Public Schools, in an exploration of citizenship. The idea sprouted from the Children Are Citizens (CAC) project in Washington, DC. The CAC project coordinates collaboration between schools (public, private, and charter) and three civic or cultural centers to connect children to the city.

The CAC project is premised on the belief that young children are not just future citizens but present-day citizens with the right to express their opinions and engage in the cultural and civic activities of their city (Project Zero 2016). They have a right to understand their roles as “citizens of their classroom, their schools, and of the larger community” (Mardell 2011, video). While previous CAC work focused on 4- and 5-year-olds, I wondered how I could help my 3-year-olds develop a better understanding of citizenship and meaningfully connect them with our city.

I have long believed that being inclusive and caring for others are part of what constitutes a good citizen. These aspects of citizenship build on the set of conditions I establish in my classroom every year, such as respectful exploration, idea sharing, and open communication. By setting the groundwork cognitively, socially, and emotionally, I convey to the children that we are citizens of the classroom. The CAC project provided an opportunity to extend our classroom conditions and ideas about citizenship outside the walls of our school and into the wider community of Washington, DC. But how, exactly? I decided to leave that up to the children.

The following questions guided my teacher research study:

- How can I expand my 3-year-olds’ understanding of citizenship beyond the classroom?

- How can I use the rich cultural resources of Washington, DC, to foster the idea of citizenship?

- How can I listen closely to the children and document my observations to help them guide the project?

- When I allow children to guide the project, what are the results?

Conceptual foundation

When my preschool class ventures out from the classroom on field trips, strangers often smile and comment on how adorable they are. Although the  children may appreciate the attention, labeling them cute is demeaning. It disempowers them: “cuteness is ultimately dehumanizing, paralyzing its victims” (Harris 1992, 180). The label of cuteness ignores what children can contribute as citizens of their community: innovative ideas, a unique perspective on the world, and real relationships with adults. Children are capable. And because they are capable, they deserve to be recognized as citizens and given a place in our collective efforts to solve important problems.

children may appreciate the attention, labeling them cute is demeaning. It disempowers them: “cuteness is ultimately dehumanizing, paralyzing its victims” (Harris 1992, 180). The label of cuteness ignores what children can contribute as citizens of their community: innovative ideas, a unique perspective on the world, and real relationships with adults. Children are capable. And because they are capable, they deserve to be recognized as citizens and given a place in our collective efforts to solve important problems.

CAC projects in Providence, Rhode Island, and Washington, DC, were a constant source of inspiration for my teaching. In 2011, the mayor of Providence asked preschoolers to write on their area of expertise—places to play (Mardell & Carpenter 2012). This engagement of an important public figure elevated the importance of the project in addition to placing children in the role of the expert (Krechevsky, Mardell, & Romans 2014). In 2014–15, children in Washington, DC, were invited to explore and research topics about their city that inspired them, from museums to parks to the metro system.

Another source of inspiration was the Reggio Emilia philosophy that insists children are protagonists and therefore active participants in directing their lives and learning (Krechevsky et al. 2016). (Reggio Emilia is a city in Italy known for its high-quality early childhood education.) I intended that the 3-year olds would be the protagonists of their classroom, actively directing their learning (Krechevsky, Mardell, & Romans 2014). To extend their learning environment from the classroom to the city, I borrowed an idea from Graziano Delrio, a former mayor of Reggio Emilia, Italy, who wrote:

Responsibility toward children concerns ethical liability. Ethical liability toward children means that you recognize their dignity as citizens, as bearers of rights related to the city. The child is, therefore, a competent citizen. He or she is competent in assuming responsibility for the city (Delrio 2012, 83).

To begin, I sought to engage the children in a democratic way by building on their current knowledge of citizenship. This was the starting point for them to determine the direction of the project (Biermeier 2015).

Methodology and research design

Since I intended for this to be an emergent, child-directed project, at the outset I simply asked the children, “What is a citizen?” to encourage them to share thoughts and opinions. This is a key point of Reggio Emilia’s philosophy, in which children actively engage their minds and hands to experiment with ideas (Davoli & Cagliari 2003). Conversation, artwork, dramatic play, early writing, and other outlets nourish the children’s creativity and desire to express themselves.

As the children began grappling with the question, I collected data and documented their communication both in the classroom and on our field trips. I recorded group conversations, collected artwork, and took photographs. I observed the children at play and transcribed their conversations. On field trips, the children documented their activities and thoughts by drawing; I encouraged adult chaperones to be mindful of the children’s voices and transcribe the children’s words as they drew. Many parents volunteered to participate in our field trips and became adept at documenting. Documenting was necessary for my planning, and for helping the children reflect on and guide the project. It also had a side benefit—it was easy for me to keep parents informed about our project with weekly newsletters.

Visual and verbal documentation allowed me to observe the children, reflect upon their learning, and inform my analysis. I reviewed the details after school and used them to ground conversations about the project with my colleagues at school and CAC. My reflection on the material and the project as a whole led to the creation of the narrative that follows.

“The Happiness Project”

“What is a citizen?” is a brief, yet challenging question that worked well to sow the seeds of enquiry. The children were full of ideas, and soon were building on their classmates’ thoughts:

Christine: People!

Jim: But what about orca whales?

Ben: Octopus!

Teacher: So can animals be citizens?

Children: Yes.

Teacher: What about plants? Plants are alive as well; can they be citizens?

Children: Yes.

Our classroom spent the following three weeks discussing citizenship while I sought ways to help them explore the concept. Gradually, our initial working hypothesis took shape: a citizen is “a person, big or small, an animal, or a plant that lives in Washington, DC.” I reinforced the elements of early literacy with letters and words to make a statement of our hypothesis; we signed it collectively with our child-chosen class name, “The Statues,” and each child added his or her own signature. Then, the children eagerly explored ideas and gathered data to test their hypothesis.

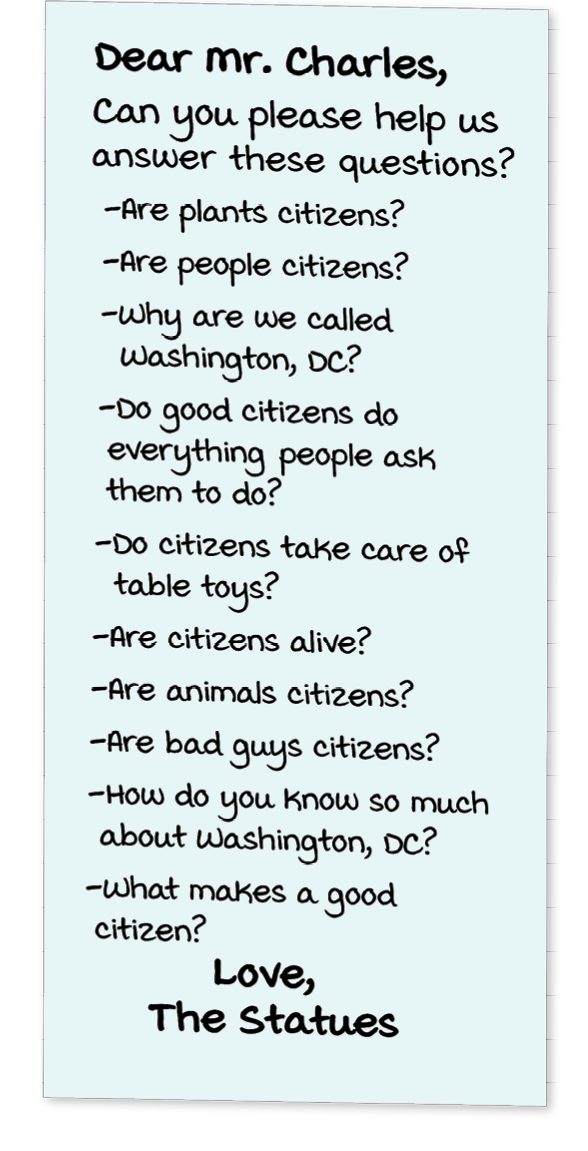

We decided to compose a letter to experts accessible to the classroom. Ms. Shoshana, our gardening teacher, offered her expert perspective on plants: “Yes, of course, plants are citizens because they are alive.” Next we invited Charles Allen, our local city councilmember, to our classroom

Our letter of invitation read:

The children enthusiastically prepared for Mr. Allen’s visit. It was important to build on the elements of early literacy to convey their thoughts to Mr. Allen and make his visit meaningful for them. Every one of the children had an index card with their question on it and a pictorial representation that would help them remember the question.

The interview included the following dialogue:

Jim: Are people citizens?

Mr. Allen: Yes, we are all citizens.

Christine: Are plants citizens?

Mr. Allen: I like trees and plants, but they are not citizens.

Heidi: Are citizens alive?

Mr. Allen: Yes, they are alive. We need to be able to talk and communicate with citizens.

Mara: Are animals citizens?

Mr. Allen: If I were to ask the bunny what he wanted, would he be able to tell me? He wouldn’t, but while he’s not a citizen, we all still care for animals. [The children were alert to the newsworthy bunny reference. The day before Mr. Allen’s visit, we received a foster bunny for our classroom.]

Elizabeth: Are birds citizens?

Mr. Allen: No, they are not citizens.

Kristen and Ben: Do citizens take care of table toys?

Mr. Allen: Absolutely! Good citizens take care of their table toys and the space they use, including the classroom and their neighborhood.

Tamika: What makes a good citizen?

Mr. Allen: Take care of your community. Take care of the outside. Be nice to people. Follow the rules. Next week you’re going to visit the Wilson Building [the capitol building of the District of Columbia] where I work and where people in government make lots of decisions.

Janet: I didn’t even know that!

Mr. Allen: What you can also do with a letter is to ask for things, such as clean rivers or safe playgrounds. It’s important that you tell people who are elected to represent you what you want them to focus on, or what your community needs. I’m looking forward to seeing you next week at our capitol!

The turning point

After this visit, I wanted to help the children think more deeply about Mr. Allen’s responses. To enhance their memories and spur discussion, I shared documentation of Mr. Allen’s visit visually and through documentation panels with a transcript of the conversation. As I read portions of the transcript with the children, they seized on Mr. Allen’s comments about writing letters and being kind to people. This marked a turning point in the project—the children were taking charge of guiding it.

Spreading happiness through letters emerged from the children.

The children already knew the joy of receiving mail; they loved to send postcards to the classroom from their adventures around the city and beyond. We had classroom mailboxes for each child and they often wrote letters to themselves, their friends, and their families. The concept of being kind—and spreading happiness—to strangers through writing letters soon emerged from the children. In the message center, I heard Stephanie and Alex discuss what came to be the project’s pivotal question: “Can we make other people happy who are not in our classroom?” During our class reflection meeting (after center time), we shared this key question with our class. The children figured a card would be the best way to reach out, but this led them to wonder: How could we disseminate our cards to people who don’t have classroom mailboxes? Could we bring mailboxes on our field trips?

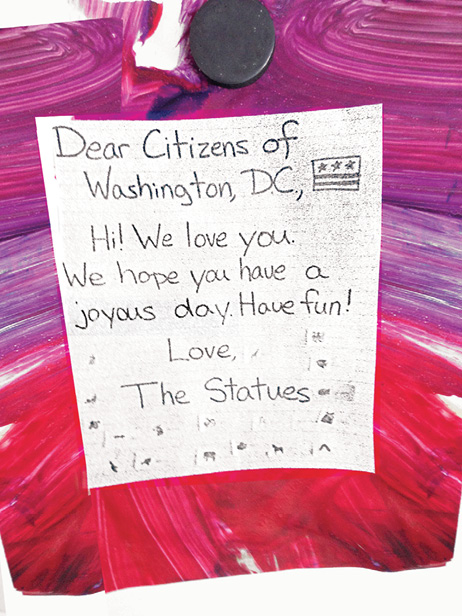

After deciding that their ideas could be pursued safely, I asked the children a series of questions to help them plan their project. What would the cards look like? What do we want to say in our cards? Did we really think that if we gave this to someone, it would make them happy? To find out, we decided to write cards, sign them with animal symbols chosen by the children,and deliver them on our first field trip to the Wilson Building.

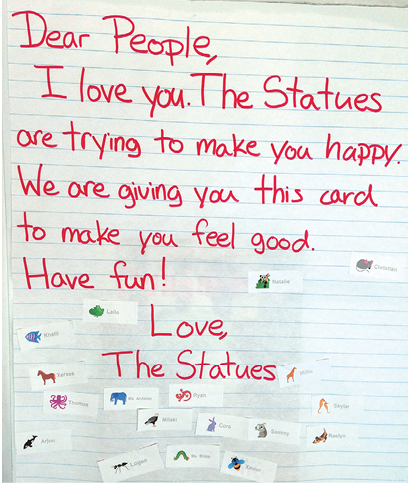

The children wrote:

To carry their cards, the children created mailbags made from donated curtains and staples. (These bags were perfect for carrying their documentation tools—clipboards, paper, and pencils—too.) Before we embarked on our field trip, we created some safety rules for sharing the cards. The children had to hold an adult’s hand; they could give cards to parents, people who walked near us, bus passengers, and bus drivers. We also thought about the words to begin conversations: “Here is a special card for you!,” or as Kristen remembers, “We have a card for you to make you feel happy, too!”

As we made our way to the Wilson Building, the children began to deliver their cards. During our break in Mr. Allen’s office, they gave his staff cards. The children also gave cards to the mayor’s chief of staff and other staff members. By the end of our tour, the Statues were so excited from the positive responses that some people even got two cards.

The recipients warmly responded to the children’s enthusiasm. To document the results of their efforts to spread happiness, the children made drawings of the recipients of the cards while their adult chaperones wrote down what the adult recipients said:

“I am going to really enjoy my day, you know why? Because you opened up your heart to me. Thank you, baby!” “Can I have this card, even if I am not a citizen of Washington, DC? I am going to take it back to Italy!”

Reflecting, improving,

and trying again

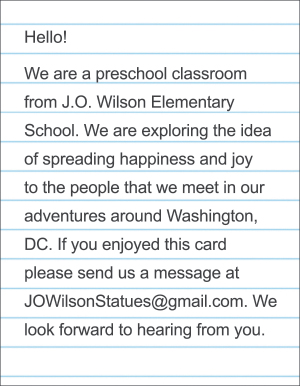

Ever since they learned from Mr. Allen that kindness is a part of citizenship, the children’s questions and discussion always returned to the challenge of how to spread happiness. Pleased with, but not confident in, their efforts to date, their thoughts turned into a question: “Did our Spreading Happiness card actually make that person happy?” I steered the children to discuss questions that we were more likely to be able to answer: “What happened to the cards after we gave them out? Were the cards trashed or treasured?” We thought about a world in which people smiled at each other and did not want anything else but to brighten someone’s day. Would a card affect people’s outlook on the world? The children loved the experience of handing out the cards and decided they wanted to spread more happiness. They elected to pass out more happiness cards on our remaining field trips in the city.

This time, the children wanted

more evidence as to how

successful they were in making

people feel happy, so we created an email address and pasted it on the back of each card along with an explanation of our project:

We also thought about how to

improve our card. Upon reflection,

we realized we should address it to

“People” instead of “Citizens of

Washington, DC,” because we

understood, thanks to an Italian

recipient, that people we meet

might not be DC residents.

After the Wilson Building, we visited the National Gallery of Art, Atlas Theater (twice), National Building Museum, and the White House. These places lay in waiting for The Statues, our 3-year-old citizens, to awaken the city through their ideas (Guidici, Rinaldi, & Krechevsky 2001). As citizens, children play an important part in the well-being of their community.

As citizens, children play an important part in the well-being of their community.

The security guard at the National Gallery, the construction worker on the sidewalk, and the visitor to the White House all responded to the children. During our six field trips, we gave out about 300 cards and received about 20 personal email messages. Here are a few representative responses: “Do you know what? You made me very happy today when one of you gave me a card! I will keep it on my desk at work and every time I see it, I will smile.”

“I like your little mailbags, too, and I bet it is fun to wear them and to give out a card and surprise people.”

“They say it’s the small things that count, and you Statues are pretty amazing and make such an impact!”

“Thank you for the sweet note you shared at the National Gallery on Wednesday, May 11. It was a rainy, dreary day, and your note spreading happiness and joy made us all smile. It made my day and I am saving it, as it will make me smile whenever I look at it!”

“I wanted you guys to know I was having a very sad morning and when you guys gave me the card I almost cried because I thought it was so sweet and awesome! Keep spreading the joy and happiness; it’s contagious! Thank you :)”

Conclusion

Our “Spreading Happiness” project empowered the children to peel back their cuteness label and initiate a meaningful relationship with adults. It proved that we do not have to wait until we are 18 to take civic action; in fact, this can begin at the foundation of children’s education. Education has morphed from learning a vocation into embracing citizenship. Civic agency involves three core tasks: assembling publicly for deliberation around a problem, working to shift the mindset of the public, and having a public figure who adopts the cause (Allen 2016). Our project proved that our youngest learners are capable of engaging in their cities and of understanding their responsibilities: as citizens in the here and now, they play an important part in the well-being of their school and community.

Spreading the Happiness: By Seeing Children as Citizens, a Teacher Helps Them Be Big

Ben Mardell, Voices Executive Editor

Big and small

I imagine many early childhood educators have had experiences similar to this one. Early in my teaching career I was out for a walk when I ran into one of my students and her family. At school Nora was a leader, full of ideas for play, theories of how the world worked, and insights into the feelings of others. Talking to Nora I would sometimes forget that she was only three—she was just another person to me. She was big. But that day, seeing her teacher outside of the context of school, Nora shrank. Hiding behind her mother, barely able to talk, she seemed so small.

I have observed this phenomenon many times: young children are both big and small. By big I mean young children’s insightful ideas, creative drawings, block structures, and their capacity to bestow acts of kindness. By small I mean their physical size and dependency on adults. Whether children appear big or small—both to adults and to themselves—has a great deal to do with the context and how they are treated.

Helping children be big: Children are citizens

The 3-year-olds in Georgina Ardalan’s Washington, DC, public school prekindergarten are big. They have important and thoughtful conversations about citizenship. They apply their emerging literacy skills to effectively communicate with each other and people outside their classroom. They reach out to members of their community in frequently successful attempts to make others feel happy.

The children’s bigness did not just happen. Ardalan provides a context for them to explore ideas, collaborate, and connect with the community. She listens to them carefully. She documents their ideas and uses the documentation to reflect on their thinking (Krechevsky et al. 2013). Based on what she is seeing, she provides experiences and resources to support children’s individual and collective understandings. By seeing them as citizens—of their classroom and their city—she creates opportunities for the children to be big.

Political scientist and classicist Danielle Allen, building on Hannah Arendt’s work, takes citizenship to be “the activity of cocreating a way of life, of world-building. This cocreation can occur at many social levels: in a neighborhood or school; in a networked community or association; in a city, state, or nation; at a global scale” (2016).

But how can young children, inexperienced in the ways of the world, participate in world building? For those of us who know preschoolers, the answer is clear—in many ways. Children can create stunning works of public art as they have in Reggio Emilia, Italy (Vecchi 2002; Krechevsky et al. 2016). They can contribute to planning urban spaces as they have in Boulder, Colorado (Hall & Rudkin 2011). They can respond to an invitation from the mayor with creative ideas to make the city fairer and more interesting to children as they have in Boston (Haywoode 2016). Children can share compelling and fanciful stories about their city as they have in Washington, DC (Krechevsky, Mardell, & Reese 2017). And they can, as Ardalan’s children do, share kindness with their fellow citizens.

In The Kindness of Children kindergarten teacher and educational theorist Vivian Paley explores how young children can teach older children and adults important lessons about caring and compassion. Paley shares examples of what can be called a “multiplier effect,” in which young children’s acts of kindness spread by inspiring acts of kindness in others. Paley notes that this spreading of kindness is “a remarkable gift to bestow” (1999, 58).

We are fortunate that Ardalan chronicles how her students spread kindness, or as they refer to it, happiness, throughout Washington, DC. By handing out their happiness cards as they travel around the city on numerous field trips, the children’s simple message of love brightens the days of others. As one recipient of their message wrote to the children:

I wanted you guys to know I was having a very sad morning when you gave me the card. I almost cried because I thought it was so sweet and awesome! Keep spreading the joy and happiness—it’s contagious. Thank you :)

Teachers telling stories: Narrative as research

Reading Ardalan’s article one cannot help but think of Paley, the consummate teacher storyteller. In The Boy Who Would be a Helicopter (1990), The Girl with the Brown Crayon (1998), Wally’s Stories (1981), and other publications, Paley vividly describes classroom life, children’s thinking, and teacher decision making in story form. The result is an important body of insights about teaching, learning, and what it means to be a person (Cooper 2009).

Cochran-Smith and Lytle define teacher research as “systematic, intentional inquiry by teachers about their school and classroom work” (1993, 24). Ardalan undertakes such systematic examination, recollecting, rethinking, and analyzing her children’s learning and her teaching practice through a close look at documentation (e.g., children’s work, recordings of conversations). She uses this reflection to construct, like Paley does, a story about the children’s learning. Jerome Bruner (1987) famously explained how narrative—the creation of stories—is a central strategy for meaning making. This narrative approach to meaning making is the research orientation Ardalan employs.

A call for kindness and the need to help children be big

Writing about the preschool years, Erik Erikson observes, “The child is at no time more ready to learn quickly and avidly, to become bigger” (1950, 258). As we see with Ardalan’s students, a good preschool classroom is the perfect place for children to become bigger.

As we move further into the 21st century, events around the globe make clear the need for kindness—for compassion, caring, and the desire to help others. And kindness, as Paley observes, is something that “children already know and can teach us.” Children can “remind us who we were and can be again” (1999, 129). It is a wonderful coincidence that in becoming bigger, young children as citizens enrich their communities.

References

Allen, D. 2016. “What Is Education For?” http://bostonreview.net/forum/danielle-allen-what-education.

Biermeier, M.A. 2015. “Inspired by Reggio Emilia: Emergent Curriculum in Relationship-Driven Learning Environments.” Young Children 70 (5): 72–79.

Davoli, M., & P. Cagliari. 2003. “Reggio Tutta: The Evolution of a Research Project.” Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Exchange10 (3).

Delrio, G. 2012. “Our Responsibility Toward Young Children and Toward Their Community.” Chap. 4 in The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation, eds. C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman, 81–88. 3rd ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Guidici, C., C. Rinaldi, & M. Krechevsky, eds. 2001. Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners. Reggio Emilia, Italy: Reggio Children.

Harris, D. “Cuteness.” 1992. Salmagundi 96: 177–86.

Krechevsky, M., B. Mardell, & A.N. Romans. 2014. “Engaging City Hall: Children as Citizens.” The New Educator 10 (1): 10–20. www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Engaging%20City%20Hall%20-%20Chil....

Krechevsky, M., B. Mardell, T. Filippini, & M. Tedeschi. 2016. “Children Are Citizens: The Everyday and the Razzle-Dazzle.” Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Emilia Exchange 23 (4): 4–15. https://reggioalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Innov.23.4web-1.pdf.

Mardell, B. 2011. “Learning Is a Team Sport: Kindergartners Study the Boston Marathon.” www.pz.harvard.edu/resources/learning-is-a-team-sport-kindergartners-stu....

Mardell, B., & B. Carpenter. 2012. “Places to Play in Providence: Valuing Preschool Children as Citizens.” Young Children 67 (5):76–78.

Project Zero, Harvard University Graduate School of Education. 2016. “Children Are Citizens.” www.pz.harvard.edu/projects/children-are-citizens.

Photographs: courtesy of Henry Ackerman, Georgina Ardalan, Jordi Hutchinson, and Pamala Trivedi

Georgina Ardalan is an early childhood educator at J.O. Wilson Elementary School, a District of Columbia Public School. Georgina draws on inspiration from her first career in architecture to create a nurturing and collaborative environment within a thinking culture where teachers and children both question and listen.