Think Nationally, Act Locally: Early Childhood Education’s Role in Closing the Achievement Gap

You are here

In traditional measures of school success, there is extensive documentation of Black and Latino children, as well as children from lower-income families, trailing White and Asian children and children from wealthier families. These measures are not perfect; they miss many of our children’s strengths. Still, despite their faults, they are strong indicators of future employment prospects. Hence, NAEYC’s 2009 position statement on developmentally appropriate practice highlights the need for early childhood education to be a major force for reducing the achievement gap.

The Black Caucus, an NAEYC Interest Forum, for nearly 50 years has provided a community of support and mentoring for Black members of the larger association as they strive to improve learning environments of Black children and other children of color. The Caucus is pleased to partner with NAEYC on this special issue of Young Children. Decades of research have firmly established that the achievement gap takes hold at birth, persists throughout development, and has lifelong negative consequences—unless it is addressed early. This last finding is of the utmost importance; the achievement gap results from the inequitable opportunities provided to our children, families, and communities. As a nation, we could—and should—do far more to equalize opportunities to learn.

The authors of the articles in this special issue are well versed in the significant body of scholarly literature focused on the shortcomings of the term achievement gap. A fundamental criticism is that achievement gap is pejorative; it blames the victims, the children. Because many scholars prefer to focus on the causes of disparate outcomes in academic achievement, the term opportunity gap has become popular.

Indeed, opportunity gap captures those policies and practices that trap far too many children in a downward spiral. In some communities that have been starved for resources across generations, there truly does appear to be a cradle-to-prison pipeline. Specifically, children of color from low-income families typically attend under-resourced schools and live in under-resourced neighborhoods. They are disproportionately penalized in a climate of zero tolerance, and more often than not, they are viewed as having an array of cultural and cognitive deficits, while their personal and cultural strengths are unrecognized or ignored.

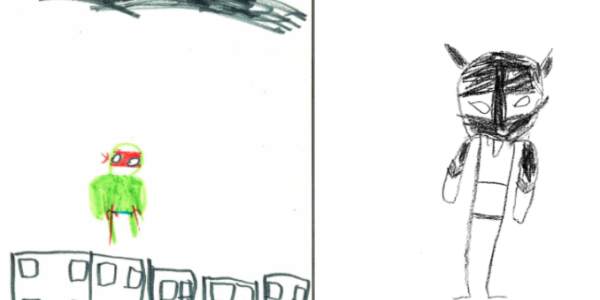

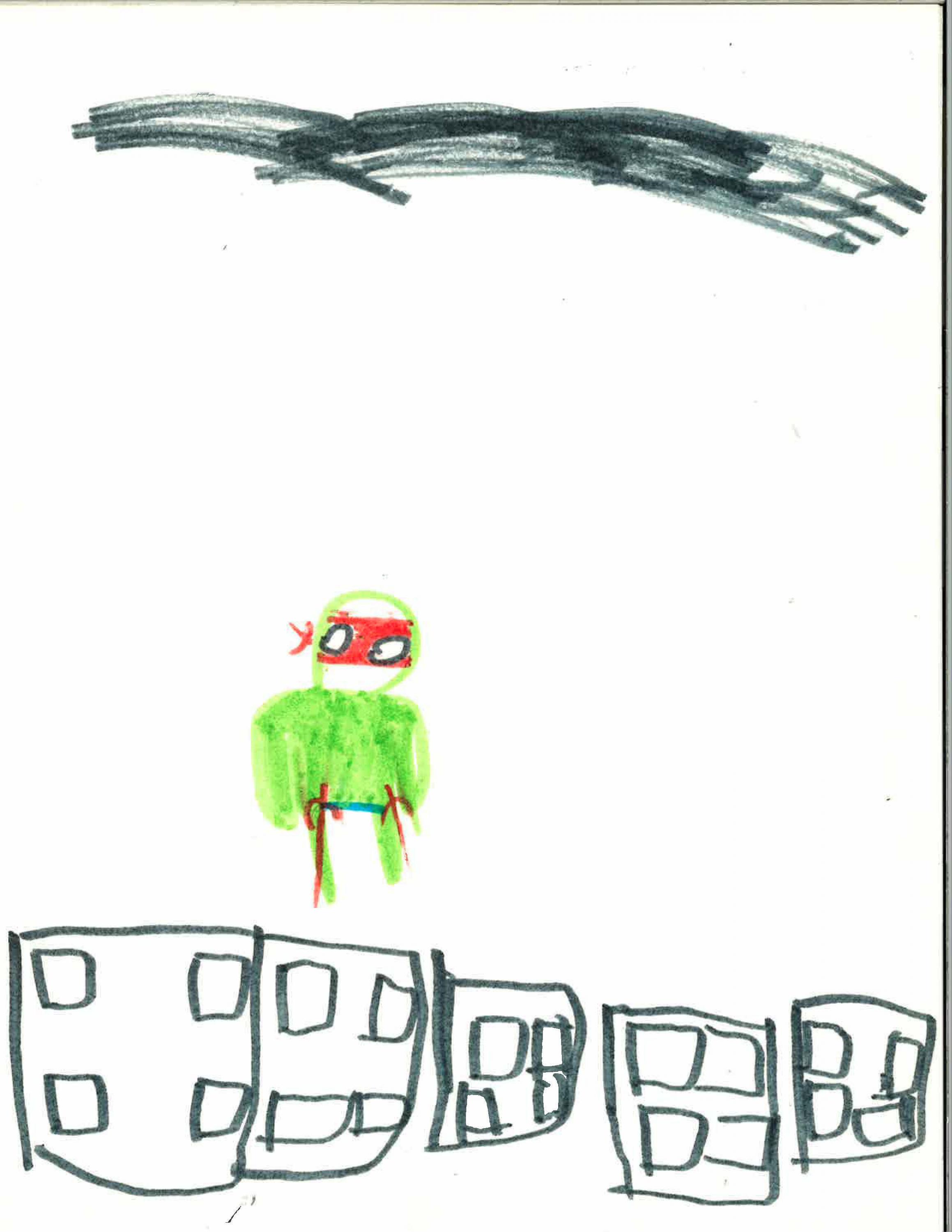

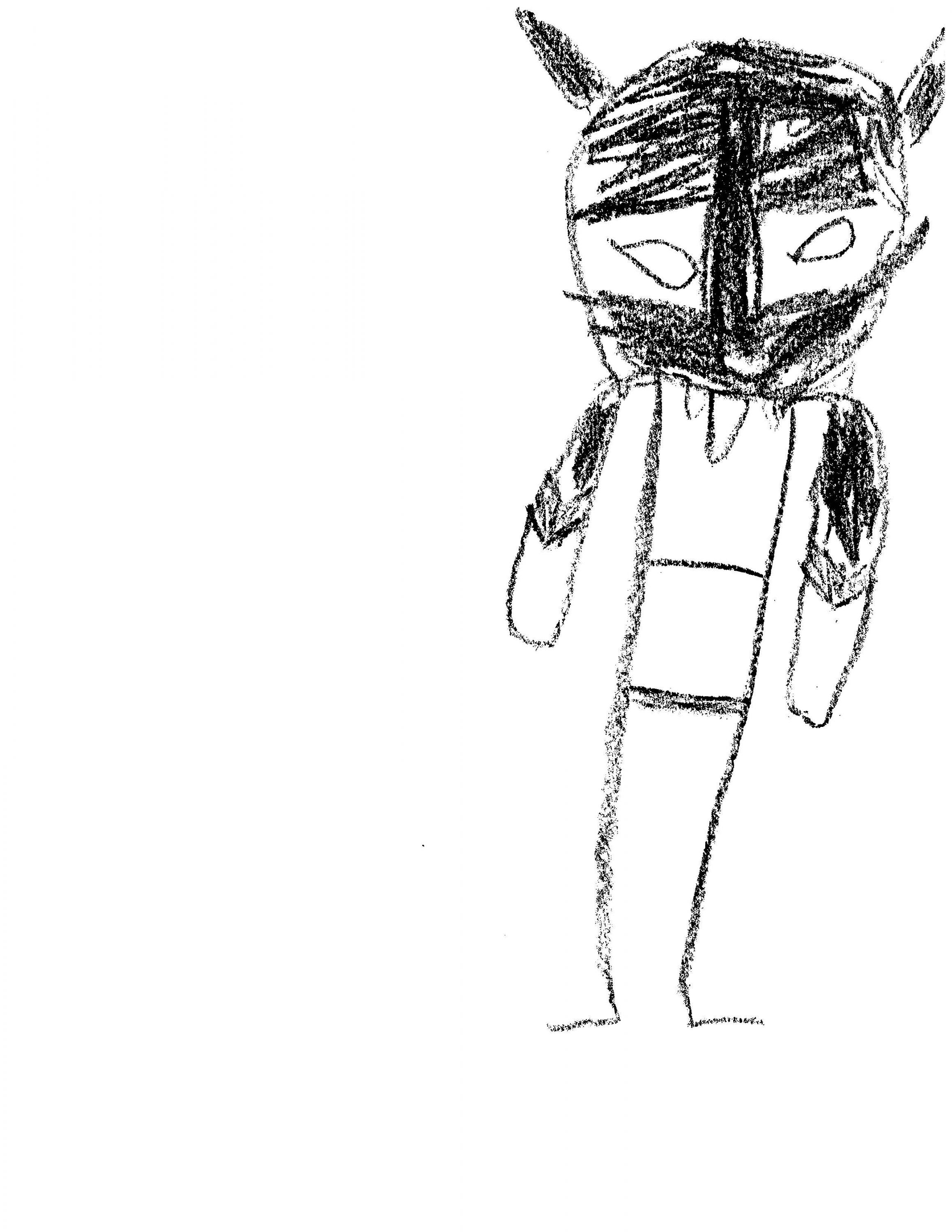

I asked three African American children to draw pictures of what they wanted to be when they grew up.

J’vion, age 6, chose a basketball player. He loves sports and is also enthralled by the magical power of the written word. Saniya, age 6, chose a nurse and an artist. She clearly sees herself in those roles down to her skin color and her braids.

With these important considerations in mind, the authors herein focus on the achievement gap to underscore the factors that educators, administrators, and professors could most readily address (instead of being distracted by the many complex social and economic factors that produce the opportunity gap). The authors have not lost sight of the tenets of developmentally appropriate practice pertaining to social and cultural contexts for learning. Borrowing from the environmental movement, these authors ask educators, administrators, and professors to think nationally, act locally.

The primary focus of this special issue of Young Children is teachers’ decision making and actions within the social and cultural context of developmentally appropriate practice—particularly as it pertains to Black children. “Addressing the African American Achievement Gap: Three Leading Educators Issue a Call to Action,” by Barbara T. Bowman, James P. Comer, and David J. Johns, sets the framework for this issue. The authors examine cultural transmission in the face of discrimination, poverty, and toxic stress. Then they contextualize cultural transmission from the perspective of schooling and consider the preparation educators need to surmount these challenges.

The articles that follow expand on many of the issues raised by Bowman, Comer, and Johns. Tyrone C. Howard, in “Capitalizing on Culture: Engaging Young Learners in Diverse Classrooms,” offers evidence of the specific strengths—the cultural capital—that young children bring to the educational setting. Such capital is a critical aspect of scaffolding children’s learning, contributing significantly to children’s persistence, motivation to learn, and resilience. Howard provides a framework for thinking about how to incorporate the knowledge and strengths children bring with them. In “A Reason for Hope: Building Teachers’ Cultural Capital,” Maurice Sykes expands on Howard’s article by recalling a teacher preparation program in the 1960s that taught him to become deeply involved in the community in which he was teaching—and to build on its strengths.

In “Becoming Upended: Teaching and Learning about Race and Racism with Young Children and Their Families,” Kirsten Cole and Diandra Verwayne explore thoughts and feelings that adults may bring from their childhoods (often without reflection) and how they influence teaching and parenting. To act on their good intentions, teachers need to plan thoughtfully and engage parents early so that the adults in young children’s lives can support each other when potentially uncomfortable, socially loaded topics are part of the curriculum.

The achievement gap takes hold at birth, persists throughout development, and has lifelong negative consequences—unless it is addressed early.

Danielle B. Davis and Dale C. Farran unravel how preschool-age African American boys are left behind in mathematics, a crucial content area. Their article, “Positive Early Math Experiences for African American Boys: Nurturing the Next Generation of STEM Majors,” is an excellent application of the tenets of developmentally appropriate practice, requiring teachers to be fluent in child development, mathematical learning progressions, and the cultural context of individual children. Davis and Farran include specific suggestions for fostering positive math outcomes.

Elijah, age 4, is fascinated by superheroes. He drew two, the first flying over buildings and the second after he saw the Black Panther movie, which was full of powerful people who look like him.

Finally, “Engaging and Enriching: The Key to Developmentally Appropriate Academic Rigor,” by Shannon Riley-Ayers and Alexandra Figueras-Daniel, broadens the achievement gap lens of this special issue by examining the use of meaningful, contextually rich language with kindergartners who are learning a second language. The authors share the journey of a small group of teachers as they grow to see the value of allowing more time for child-directed approaches to learning.

The achievement gap is indeed persistent. Yet each of the articles in this special issue offers us a fresh start—an opportunity to bring renewed energy to ensuring that all children reach their full potential.

We’d love to hear from you!

Send your thoughts on this issue, as well as topics you’d like to read about in future issues of Young Children, to [email protected].

Would you like to see your children’s artwork featured in these pages? For guidance on submitting print-quality photos (as well as details on permissions and licensing), see NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/authors-photographers/photos.

Jerlean Daniel, PhD, is a past president (1994–1996) and former executive director (2010–2013) of NAEYC. She serves as cochair of the NAEYC Black Caucus. [email protected]