Looking at the World: Children and Science

You are here

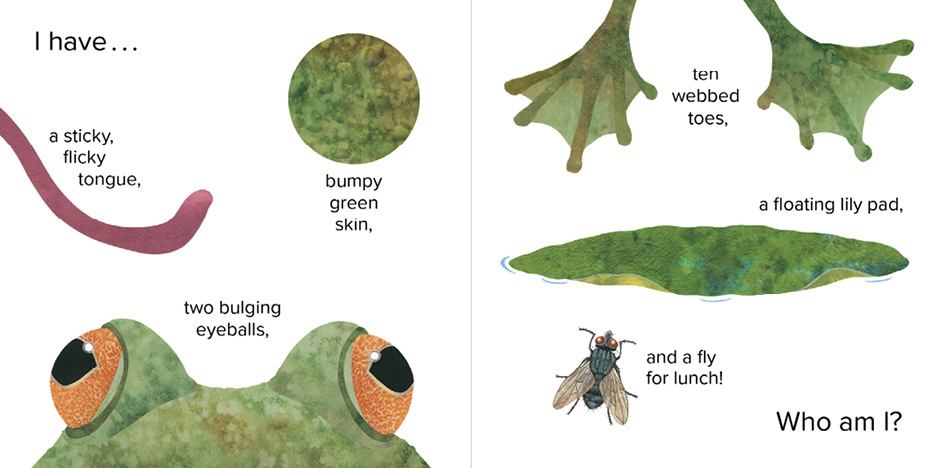

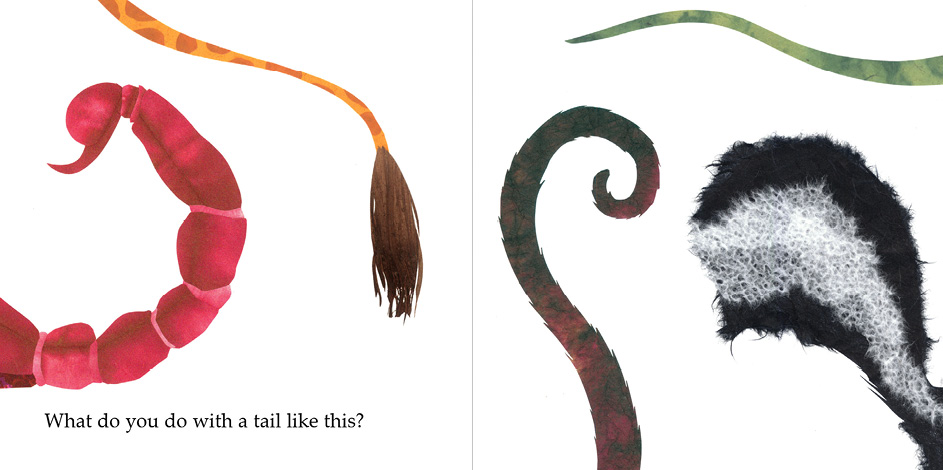

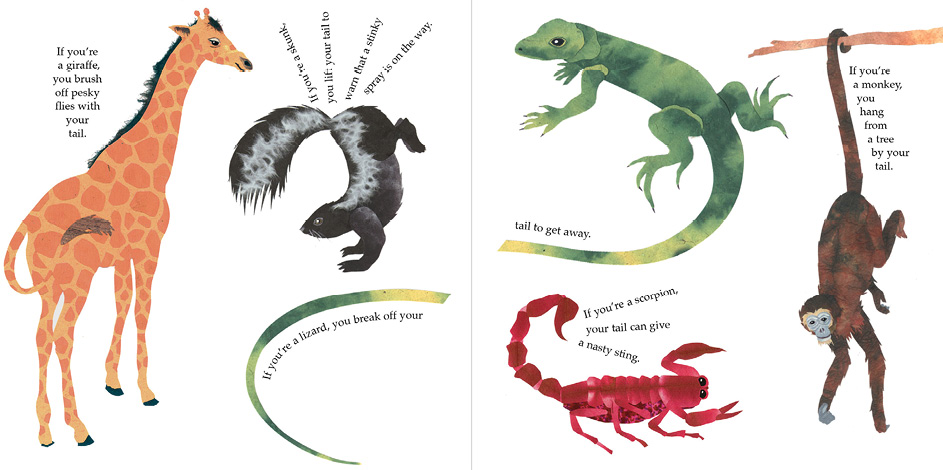

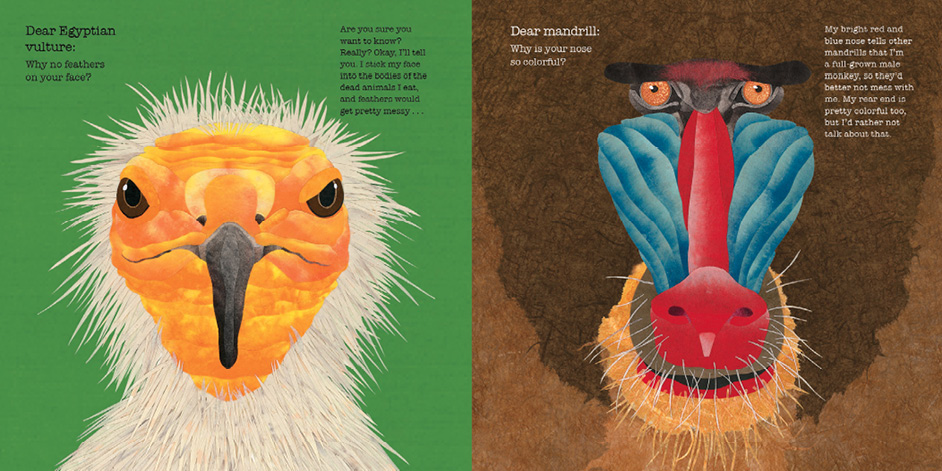

I write nonfiction picture books about the natural world for young children. Many of these books are about animals and why they look and act the way they do; others explore earth science, weather, Mount Everest, space, and time. In one way or another, they are all science books. With perhaps one exception (Life on Earth: The Story of Evolution), these books don’t explicitly define science or explain the scientific method. Instead, they each look at some aspect of the world and ask why it is the way it is: Why is a flamingo pink? Why are snails slimy? Why do the continents seem to fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle?

The ideal audience

In many ways, preschoolers and elementary-grade children are the perfect audience for books about nature. They are inherently curious. They want to understand how things work. And unlike many adults, they don’t have a lot of preconceptions or cultural biases that make it difficult for them to see things in new ways. Still, writing about science for young readers can be a challenge. As children construct a picture of the world and how it works, they use what they already know as the context for making sense of new information. This is one reason it is so important to introduce science to very young children: the understandings they develop—no matter how basic or partial—provide a framework for later learning.

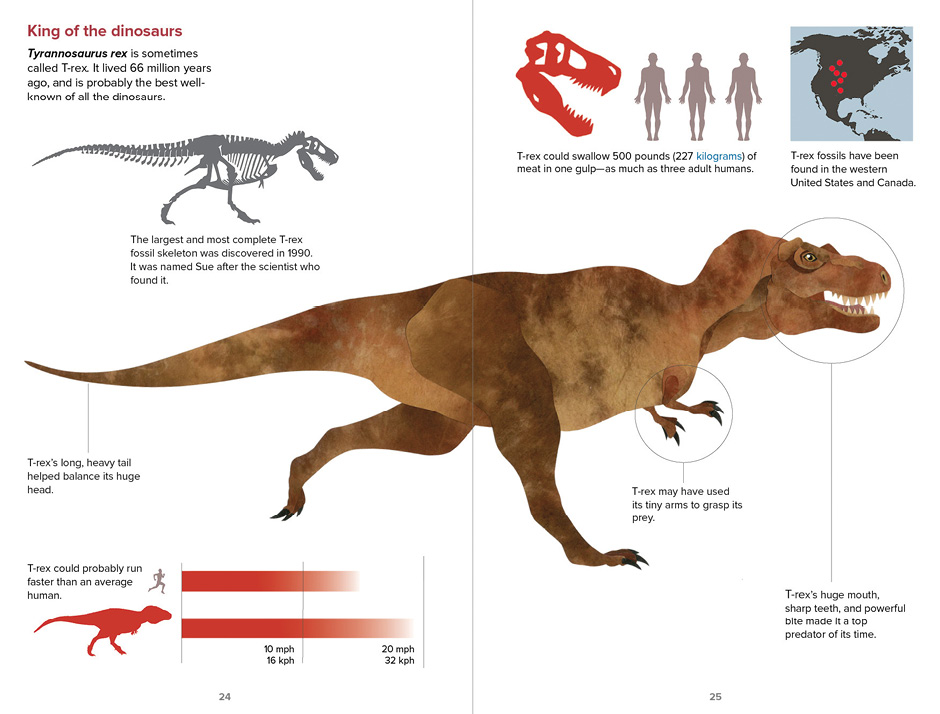

Building on one of the concepts that little people in a big world seem to intuitively understand, many of my books deal with scale: the size of things, the number of things, and the duration of things. It’s true that extremes of scale—the size of an atom, the age of the universe—are difficult for most of us, both children and adults, to wrap our heads around. But comparisons that can be directly experienced—or at least easily imagined—are more readily grasped: This is what the world’s smallest frog looks like compared with my hand. And this is what my dad would look like standing next to a Tyrannosaurus rex.

There are lots of books about the natural world that are, to my mind, not exactly science books. This is not a criticism. Books that simply show and name an animal, its color, and what it eats can spark a child’s curiosity and teach her about numbers, vocabulary, or the simple pleasure of turning pages. A science book, on the other hand, attempts to explain how being green or smelling bad helps an animal survive, or why an astronaut on the moon can jump so high. It’s an important distinction. I recognize that I’m not an unbiased observer, but I think that introducing children to the cause and not just the effect is a great way to develop deeper knowledge and encourage critical thinking. In the hands of an engaged teacher, a book that begins to explain the natural world can be the jumping off point for a child’s investigations of how and why.

What is science?

As a society, we are in a funny place—perhaps ironic is a better word—when it comes to science. We are surrounded by the products of a scientific worldview: modern medicine, air travel, the internet. Yet, in a recent Gallup poll, 38 percent of American adults agreed that humans were created in their present form within the last 10,000 years (Swift 2017). This belief is incompatible with pretty much all of modern biology, geology, astronomy, chemistry, and physics. There are many reasons for this disconnect, including religious, political, and cultural influences, as well as the inherent difficulty in grasping the extremely small and incredibly large scales, quantities, and lengths of time that are intrinsic to much of contemporary science. (But it’s best not to get me started on our nation’s scientific illiteracy; this isn’t the place for that discussion.)

Another reason that science and scientists are so widely misunderstood is especially relevant to writing about science for children. Science is, in part, a collection of facts—a body of information. But it’s much more than that. What makes science so powerful—what has made it the best (and perhaps only) tool for explaining the world and how it works—is science’s self-correcting nature. Stated more simply, science progresses by being wrong. Scientists ask questions, make observations, perform experiments, and then propose theories to explain what they’ve found. But here’s the thing about science: when a theory is proposed, other scientists immediately question it. They reexamine existing facts, gather new data, and strive to come up with an even better explanation.

When new observations are made and better explanations are offered, the old theories are discarded and the new ones accepted—at least until the process is repeated. To a nonscientist, it may seem as if science can’t be trusted. So now dinosaurs had feathers? And coffee is good for you? Skepticism about science is understandable. But it’s science’s constant questioning of accepted explanations that has allowed us to understand so much about our world. It’s why we no longer believe that the earth is at the center of the universe or that disease is caused by invisible vapors.

Bringing science-based books to children

It’s important, when we can, to explain not only what we know, but what we thought we knew and got wrong. For example, until the 1970s, it was assumed that all multicellular life on earth depended directly or indirectly on energy from the sun. Then marine scientists discovered undersea volcanic vents, or black smokers. There are entire communities of animals that derive their energy not from the sun, but from chemicals in the hot water escaping these vents.

Scientists accumulate knowledge by thinking critically about facts and theories—and about the best ways to gather more information. I believe it’s important for children to do so as well. If early exposure to science, presented in an engaging and age-appropriate way, can encourage children to question assumptions and evaluate new information rationally and impartially, we will all be better off.

In the past, an understanding of science wasn’t especially important for most people—or for society. But today’s children are tomorrow’s adults, and as adults they’ll be expected to make decisions about genetic manipulation, energy sources, artificial intelligence, and lots of things that we have not even thought about. Equally important, there is great satisfaction to be had from deducing why the world looks and acts the way it does.

The real story

All of this—the nature of science, our culture’s resistance to science, didactic strategies for writing—is important. But it’s not what I think about when I’m writing. My reasons for making books are very personal. Like many children, I was fascinated by nature when I was young. I collected rocks and fossils. I captured and cared for frogs, turtles, spiders, and other creatures. And I loved reading books about animals. Unfortunately, the nonfiction landscape when I was a kid was pretty bleak. There were bright spots—I still have some of my dog-eared Golden Nature Guides. But many “science books” were written in an insipid and condescending Dick-and-Jane style.

So far, I’ve written 40 nonfiction books. I was a good 20 books into that number before it dawned on me that what I’m really doing is making the books I would have loved to read when I was a child.

Reference

Swift, A. 2017. “In U.S., Belief in Creationist View of Humans at New Low.” Gallup Inc., May 22, 2017. https://news.gallup.com/poll/210956/belief-creationist-view-humans-new-low.aspx.

Illustrations: © Steve Jenkins

Viewpoint, a periodic feature of Young Children, provides a forum for sharing opinions and perspectives on topics relevant to the field of early childhood education. The commentary published in Viewpoint is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the view or position of NAEYC. NAEYC’s position statements on a range of topics can be found at NAEYC.org/resources/position-statements.

Steve Jenkins, an author and illustrator who lives in Boulder, Colorado, has created more than 40 nonfiction picture books for young readers. His books, many coauthored with Robin Page, all explore some aspect of the natural world.