Over the Fence: Engaging Preschoolers and Families in a Yearlong STEAM Investigation

You are here

The 26 prekindergartners at Boulder Journey School had a problem: the playground was surrounded by a tall wooden fence that prevented them from seeing what was on the other side. Over the course of the school year, they researched, designed, modeled, and redesigned solutions, which resulted in building a tree house. Their letter to future tree house users at the school explains:

We wanted to see the cars, mountains, houses, road, trees, flowers, and the people. We were climbing on the fence, and the teachers kept telling us to get down because it wasn’t safe. We were so heavy that the teachers couldn’t lift us up. We built the tree house so we could see over the fence, far, far away. We built it for people to play on, too. The next people who come can play on it too. We had to draw different tree houses and paint them. We built fake tree houses too to get ideas, and then we built a real one. The fake ones were called models. We dug deep holes first. Then our parents helped us build it.

The process of envisioning, designing, and building the tree house was typical of the way curriculum is developed at Boulder Journey School. Teachers routinely and carefully observe children’s actions to identify their interests. Combining those observations with their knowledge of child development, motivation, and learning, educators—along with children, families, and community members—engage in long-term investigations. Inspired by early childhood educators in Reggio Emilia, who view expressive languages—such as painting, drawing, and sculpting with clay—as critical components of education (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman 2011), educators at Boulder Journey School encourage children to explore ideas and subject matter using various mediums to build deep understandings. Throughout the tree house investigation, the children learned a great deal about design, measurement, engineering, aesthetics, and collaboration.

Seeing over the fence

Teachers often noticed the children’s curiosity about the happenings on the other side of the school fence. Several years ago, holes were added to the fence around the toddler playground so children could peek through. On the preschool playground, 3-year-old children climbed onto large cement tubes to see over the top of the fence. The 4- and 5-year-old children, however, struggled to see and connect with the community beyond the fence. Their playground had a few tree stumps and tires they could pile up to watch cars go by, check for different kinds of animals, and wave to cyclists, but still they were frustrated.

They explained to their teachers that the stumps tipped over, the tires did not hold enough people, and the teachers would not let them climb up on the fence because it was not safe. The children felt that the fence, intended to keep the children separated from the nearby highway, interfered with their right to participate in the world around them.

As the children grappled with their frustration, the teachers wanted to empower them. Typically, decisions concerning playground design had been made by adults based on their observations of children. This time, however, they invited the children to design and engineer their own solution to the high fence, offering a wealth of opportunities for academic, social, and emotional learning.

Nurturing a solution

Believing that learning is most meaningful when it takes place across disciplines and is rooted in developmentally appropriate practices in early childhood education (Copple et al. 2013), the teachers recognized the importance of STEAM learning, which integrates the arts into STEM: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Sharapan 2012). Solving the problem of how to see over the fence provided an excellent opportunity for STEAM learning. The children would have to be creative scientists to solve the problem in a structurally sound manner and also be creative artists to make the new structure aesthetically pleasing. In short, they would have to be designers. Design is a process that involves creativity but necessitates the incorporation of other disciplines, such as science, mathematics, engineering, and technology. It also requires organization, analysis, research, models, feedback, and revision (Catterall 2013).

Class discussions focusing on what could be done to create more opportunities for children to see beyond the fence, resulted in two possible solutions: cut holes in the fence to create windows to look through or build a platform on which to stand and see over the fence. Teachers offered children measuring materials and challenged them to think about both options. With some questioning from teachers related to structural integrity and safety, the children speculated that the windows would have to be less than five feet wide and could be shaped like triangles or squares, while the platform would need to be two yards away from the fence, 40 inches high, and have a railing. Teachers invited the children to discuss and debate the different options and found that the platform resonated with the majority of the children.

Breaking into small groups, the children began to draw and write about their many ideas for creating a platform:

- “Walls will be safer. If somebody walks off the edge, they will crack open their head.”

- “I have a different idea. We could have Zs all around the edge.”

- “We need four legs to help it stand.”

When working on complex projects such as this, teachers at Boulder Journey School recognize that there must be time for work as a large group and time to work in smaller groups. We often break into smaller groups, based on children’s interests, strengths, and availability. Small groups provide opportunities for children to engage in hands-on experiences and for their voices to be heard. The information gathered in small groups is always shared and discussed with the large group, resulting in new ideas, possibilities, and opportunities for small group work. Throughout the tree house investigation, the children and teachers flowed in and out of small and large group experiences, and all children in the class were involved in different aspects of the work.

Throughout the tree house investigation, the children learned a great deal about design, measurement, engineering, aesthetics, and collaboration.

The children used the concepts and drawings gathered during these early experiences to collaboratively create a three-dimensional structure out of clay. They discussed which parts of the clay model they wanted to work on, and as they progressed, they compared sizes to be sure that their individual pieces would fit together. They were soon referring to their platform as a tree house.

The teachers invited the children to create tree house blueprints based on the clay model, explaining that architects create drawings with measurements and specifications to be sure their ideas are clear and understandable to the builders. The children made sure their blueprints indicated that the tree house would be high enough for them to see over the fence comfortably. and they used numbers to symbolize height.

Including families in the project

After developing their blueprints, the children explained that they would need outside help to build the actual tree house. The teachers saw this as a perfect opportunity to include families in the project. They invited the children to discuss their parents’ varied knowledge and skills and how these could prove helpful.

- “My mom can help because she is a counselor, so she knows how to count really well. She is going to tell us how high to make it.”

- “My dad can help because he is strong and can build really good things.”

- “My mom can teach yoga, so she can help.”

- “My dad can help because he has lots of tools.”

- “My mom can help because she is an architect, and she builds real stuff.”

- “My mom’s a doctor; she can help too! To keep us safe.”

At Boulder Journey School, families are recognized as partners, and family members are frequently invited to collaborate in various ways in the development of long-term investigations. Therefore, the teachers were confident that there would be plenty of volunteers when the children were ready to build their tree house. To get to that point, however, the teachers realized they needed greater expertise to fully understand the design and engineering concepts inherent in the children’s tree house ideas. The teachers invited one of the parents, Lisa, an architect, to become a visiting scholar. Lisa readily agreed, recalling an opportunity she’d had to use a hammer when she was in preschool, which allowed her to define herself as someone capable of using tools. She hoped that designing and building a tree house might provide the same inspiration for all of the children in her son’s class.

Referring to the children’s clay model and blueprints, Lisa introduced the children to a computer program that could generate a three-dimensional view of the tree house. She invited the children to estimate the tree house’s dimensions by using 1-foot-square floor tiles, which they could stand on and count. The children also determined what the platform should be made of and what color it should be.

As the children’s ideas became clearer, they formulated new questions:

- Do the walls or railings have to be the same size?

- What materials would be friendliest to the environment?

- Can we choose colors based on the environment instead of the crayon box?

The children's three models show how their thinking progressed. While they began with a traditional, brightly colored playground structure, they ultimately built an organic tree house.

The National Research Council’s framework for science education asserts that practices like asking questions, defining problems, developing and using models, planning and carrying out investigations, and analyzing and interpreting data are critical to developing scientific thinking (NRC 2012). The teachers were delighted to see this design project begin to deepen and broaden children’s thinking. Rather than settling on a design at this point, the children asked new questions to refine their design process.

Child care licensing regulations require that preschool playground structures be no higher than three feet. The children worked in small groups to determine if a three-foot platform would be high enough for everyone to clearly see over the fence. One group began by standing on the ground. Anton explained, “We can see through the cracks.” When Liam looked, he said, “We need to see better.” Next, they brought over tires. After measuring one, they discovered it raised them eight inches off the ground. Liam declared, “We need to be higher.” Anton agreed, “So we can see better.” Kavi, always concerned with safety, disagreed nervously, “No, we don’t have to be higher.”

The group convinced Kavi that they needed to try being a little bit higher, so they measured a small step stool, discovering that it would raise them about 19 inches off the ground, and climbed onto it. The children noticed the mountains in the distance and agreed that this view was a little better. Remembering they could go as high as three feet, they tried to test this last height by standing on a 29-inch-high stepladder. Sam exclaimed, “I see a house!” Brooke noticed, “I couldn’t see the yellow house before.” Anton said, “I can see the whole country and the whole world.” Liam added, “I can see that house made out of brick. I couldn’t see it on the tire.” Kavi climbed up too, saying, “I see a lot of things. I can see far, far, far.” After the group explained their findings to the rest of the class, all of the children agreed that a platform that was three feet tall would be high enough.

Designing a tree house

After this experimentation, Lisa met with a small group of children to discuss their new ideas. Reflecting on their desire for the structure to be a tree house, Lisa suggested the children use curvy, flowing, organic shapes, instead of the straight-line shapes they had been using. Again, the children used the computer program to incorporate their new ideas into the tree house design. They thought of adding vines to use for climbing, and they designed a structure that looked more like a tree and less like a house.

With these new plans, the children began creating a new model. They chose a variety of loose parts, which allowed them to conceptualize their tree house in a new way. The children carefully selected materials that would best suit their new ideas, giving their second model a more organic look. They used bendable materials to create curved walls, and they incorporated green and brown instead of the bright and varied color scheme of the first design.

At this point, teachers proposed that the children display their work in the hallway to gather feedback from other children, educators, and families. They received many valuable questions for consideration, including:

- How were the children planning to make the structure fun and safe for everyone?

- Would there be music in the tree house?

- What materials could they use to make it look more natural?

A small group of children met to address the new questions and suggestions, which were carefully considered and incorporated into the design. For example, the children decided to add wind chimes and use wood and branches to make the tree house look natural.

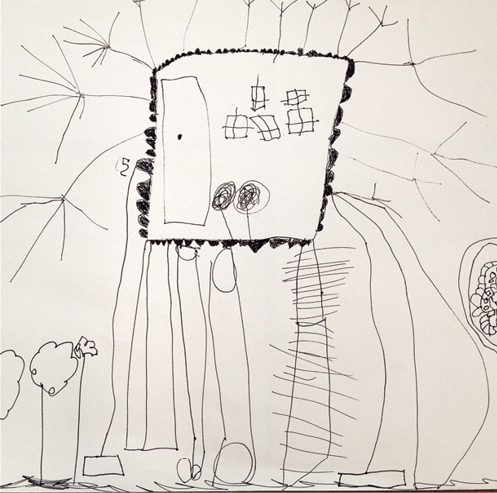

Up to this point, the children had been working in small groups to create individual blueprints, which were shared, discussed, and debated. Since their intention was to construct one life-size tree house, teachers invited the children to consider all of the ideas generated throughout the investigation and draw one final design collaboratively. The children had already gained experience with collaborative design processes by creating the clay and computer models. To compose the final design, the children used a strategy that involved the entire class, one that gave each child a turn to add various components to the tree house design. The children chose a large sheet of white paper and black pens to record their comprehensive plan.

Children's final, collaborative blueprint.

Teachers were struck by how the collaboration gave each child a sense of ownership of the design, but none of the children felt overwhelmed by the difficulty of the task. They broke the challenge into components and relied on each other’s strengths. For example, after choosing one component of the tree house on which to focus, the children decided who would draw it. The more advanced drawers took on the more advanced components, while the children who had a harder time expressing their ideas through drawing chose the simpler details. The children also offered advice to one another as they drew.

Using the final collaborative drawing as a reference, the children created one more model. They found a small piece of wood to represent the platform, twisted flexible wire to construct a frame for the walls, wove small sticks into the wire to fill in the walls, and attached larger sticks for support legs. Once the basic structure was complete, the children added details—leaves to create a slide, sticks to build a ladder, and a doll-sized whisk to represent wind chimes.

Using the children’s last blueprint and model, a final computer-generated image of the design was created. Lisa also made a list of building materials that would be needed to construct the tree house. With the final tree house design and list of materials in hand, the class discussed gathering materials to build the actual structure. The time had come to invite more families and the community to become involved.

Involving the community

The collaboration gave each child a sense of ownership of the design.

Along with parents, grandparents, and teachers, children visited local hardware stores, lumberyards, and recycling centers to research the kinds of materials that were available. They traveled to different locations in small groups and reported their findings to the entire class. Local businesses welcomed the children, who were organized and intentional about what they were seeking from each site.

Once all of the resources were in place, the class was ready to build. The children worked side-by-side with their parents and grandparents as their ideas came to fruition. When the building process began, the teachers were a little worried that the children would feel removed, seeing it as an adult project. Instead, children reported to Lisa when, according to their vision, something was too tall or a curve was not quite right. They felt ownership of the process. When parents asked Lisa where a particular board should go, Lisa turned to one of the children, since they knew the plan so well.

After six hours over two workdays, the tree house was complete, and this inventive group of children was able to safely connect with the community on the other side of the fence. In the final structure, the slight camber to the structural posts reflects the leaning of trees in a forest. The curves of the platform—drawn by children, then cut by parents—are inspired by forms in nature. The slanted railings are inspired by the weaving of materials in the children’s final model. By the end of this project, the children had designed and built a real-life solution to their problem, developed knowledge and skills across STEAM subjects, and collaborated with each other, as well as with many community and family members.

Reflecting on the project

Lisa is not a professional educator; she is a professional architect. She initially connected to this project because it provided an opportunity to support her child and his friends. By inviting her participation in a way that drew on her expertise, however, teachers were able to support the education of everyone involved. The children’s strong desire to see over the fence and persistence in refining their design inspired many family members to become involved, including the counselor, the “strong dad,” the yoga teacher, the “dad with tools,” the doctor, and many others.

The children built a real-life solution to their problem, developed knowledge and skills, and collaborated with each other and many community members.

The teachers, reflecting on the project, believed that if they had relied on the previous strategy of making decisions about playground design based on observations, but without directly involving the children, they likely would have steered the project toward small holes in the fence. The children’s determination, combined with assistance from Lisa, other families, and community members, contributed to what the teachers felt was a much more powerful and complex end result. Additionally, the teachers learned a great deal about the process of supporting STEAM subjects in the preschool classroom. Through many avenues of investigation—models, measurements, blueprints, and designs—the children developed a very clear concept of their tree house, resulting in a playground structure that is sturdy, safe, and imbued with natural beauty.

References

Catterall, J. 2013. “Getting Real about the E in STEAM.” The STEAM Journal 1 (1): Article 6. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/steam/vol1/iss1/6.

Copple, C., S. Bredekamp, D. Koralek, & K. Charner, eds. 2013. Developmentally Appropriate Practice: Focus on Preschoolers. Developmentally Appropriate Practice Focus series. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Edwards, C., L. Gandini, & G. Forman, eds. 2011. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. 3rd ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

NRC (National Research Council). 2012. A Framework for K–12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Sharapan, H. 2012. “From STEM to STEAM: How Early Childhood Educators Can Apply Fred Rogers’ Approach.” Young Children 67 (1): 36–40.

Photographs: pp. 44, 47, 48, 49, courtesy of Boulder Journey School

Lauren Weatherly, MA, is an instructor and partner school program director with the Boulder Journey School Teacher Education Program, working with educators and schools throughout the Boulder/Denver Metro area. Her work is community focused, supporting networks of educators in dialogue around quality early childhood education. [email protected]

Vicki Oleson, MA, is one of the school directors at Boulder Journey School, where she has worked since 1991. She was a preschool/prekindergarten teacher for 23 years before becoming a full-time administrator this past year. Vicki works closely with classroom communities, supporting curriculum development, family partnerships, organizational systems, and learning environments. [email protected]

Lisa Ramond Kistner, AIA, is a licensed architect based in Boulder, Colorado. She focuses on ecologically sustainable architecture in the United States and Honduras. Her work includes residential and eco-resort work that responsibly develops the land, and making social and educational connections to the local community.