Supporting Struggling Readers: Using Vocabulary Cartoons During Transition Times (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Debra Murphy, Voices Executive Editor

Small moments. So much has been written about teaching that it is easy to forget what every teacher knows: teaching is made up of small moments. Heidi’s article about using cartoons as an engaging intervention to boost the vocabularies of struggling readers does what teacher research articles do—it gives us glimpses of small moments in her practice as a reading intervention teacher.

As a teacher educator, I was drawn to teacher research because of its power to make the voices of teachers and children heard. The real power, however, emerges from why that matters so much. As Cynthia Ballenger, author of Puzzling Moments, Teachable Moments: Practicing Teacher Research in Urban Classrooms, has explained, teacher research brings democracy and equity to the classroom by giving significance to everyone’s ideas. Heidi’s article reflects this same goal with a group of children that might otherwise be invisible. She not only looked; she saw them. She not only listened; she heard them. This is the real message of teacher research. It resonates with other teachers—one teacher at a time, one small moment at a time.

As a reading intervention teacher in an elementary school, it is my responsibility to identify the knowledge and skills that struggling readers have not yet mastered and to offer targeted instruction to address their needs. Children typically make significant—even life-changing—reading progress when research-based interventions are used (Slavin et al. 2009).

After 10 years working with young struggling readers, I realized that poorly developed vocabulary knowledge seemed to be a factor limiting their ability to access more advanced texts. The reading interventions I used were highly structured and did not provide systematic vocabulary instruction, and scheduling restraints prevented additional lesson time to incorporate daily vocabulary work. Still, I was determined to find a way to supplement students’ vocabulary knowledge.

After 10 years working with young struggling readers, I realized that poorly developed vocabulary knowledge seemed to be a factor limiting their ability to access more advanced texts. The reading interventions I used were highly structured and did not provide systematic vocabulary instruction, and scheduling restraints prevented additional lesson time to incorporate daily vocabulary work. Still, I was determined to find a way to supplement students’ vocabulary knowledge.

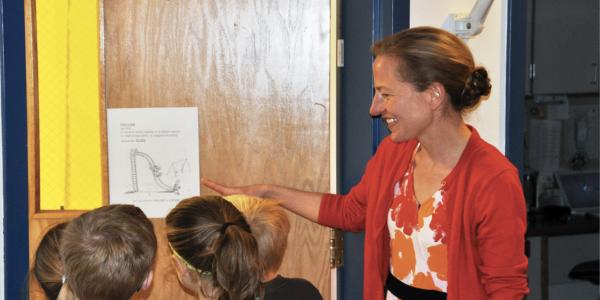

An idea began to form when I observed that the first graders I worked with were highly engaged in the conversations we had during transitions between their classrooms and my intervention room. I tried to make these conversations instructional to make every moment an opportunity to learn. For example, I gave the children clues to help them decode a mystery word taped to my door. Or I might play a rhyming game or engage in a phonemic awareness activity, such as verbally segmenting a word and asking them to identify the word. While these interactions seemed to be casual social exchanges, I had very deliberate academic goals in mind. I decided to find a way to capitalize on our transition time to enhance students’ vocabulary knowledge.

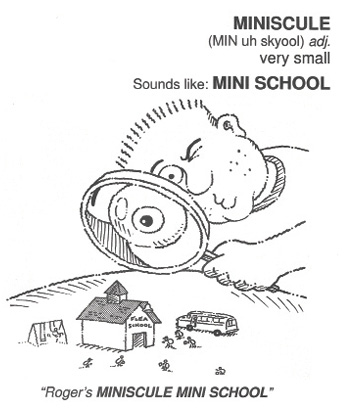

In my search for new strategies, I discovered the book Vocabulary Cartoons (Burchers, Burchers, & Burchers 1998) and was captivated by the authors’ idea of using rhyming text with silly images to support vocabulary development. The cartoons combine the benefits of humor, a rhyming mnemonic, and an image to help learners associate a vocabulary word with its meaning. I decided to explore using vocabulary cartoons during transition times to increase students’ vocabulary knowledge and hoped to answer the following questions:

- How would first graders respond to the hallway vocabulary cartoon intervention?

- Would using vocabulary cartoons during transition times help them gain vocabulary knowledge?

- Would teachers notice children using the vocabulary words in their classrooms and support the intervention?

Literature review

Vocabulary knowledge is important for reading comprehension (National Reading Panel 2000; Lervåg & Aukrust 2010), and extensive print exposure contributes significantly to vocabulary knowledge (Cunningham & Stanovich 1991). Consequently, struggling readers who have difficulty negotiating text do not benefit as much from the reciprocal relationship between vocabulary knowledge and reading experience as their peers who are proficient readers. Struggling readers typically read less and choose fewer vocabulary-rich texts due to the task difficulty (Cain & Oakhill 2011). Nevertheless, it is not unreasonable to expect young children to learn more sophisticated words (Beck & McKeown 2007).

Mnemonics are strategies used to help learners remember (Lombardi & Butera 1998). Vocabulary cartoons are similar to a method of vocabulary instruction called the keyword mnemonic strategy, which uses a paired association of imagery and an acoustical link to help learners remember new words (Wolgemuth, Cobb, & Alwell 2008). Research indicates that the keyword mnemonic approach can be effective in developing vocabulary knowledge for students with and without learning disabilities (Condus, Marshall, & Miller 1986; Mastropieri, Scruggs, & Fulk 1990; Lombardi & Butera 1998).

Humor has also been linked with helping students learn, as it may increase their interest and engagement in the material presented (Weimer 2011). Using humor in the classroom—such as cartoons and funny photos that illustrate different concepts—can help elementary and middle school students with reading, writing, and critical thinking (Ivy 2013). Younger students benefit also, as noted in a previous Voices of Practitioners article discussing the cognitive and psychological benefits of laughter in a preschool classroom (Smidl 2014). By combining mnemonics and humor in the hallway, I hoped to create a brief, effective vocabulary intervention for my first graders during transition times.

Setting and participants

The elementary school in this research study was located in a small midwestern community. While the student body (roughly 430 children) had long been predominantly white and middle class, an increasing number of children from working-class Hispanic heritage families had recently begun enrolling. This increasing diversity merited attention because our school was not fully prepared to provide high-quality, research-validated education for dual language learners. Native English-speaking children whose parents did not go to college would likely need additional vocabulary instruction, as well.

My teaching schedule included two first-grade reading intervention groups, which had been formed through recommendations by classroom teachers and assessment data. The eight lowestscoring first-grade struggling readers who were not identified for special education services were enrolled in my intervention groups and then invited to participate in my action research study. I obtained parental and child consent for all eight participants (three girls and five boys).

Methodology

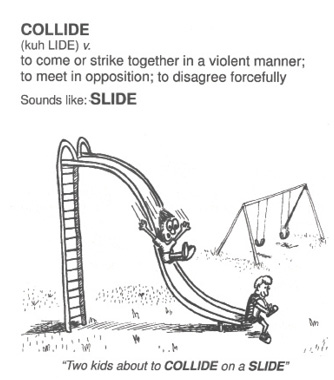

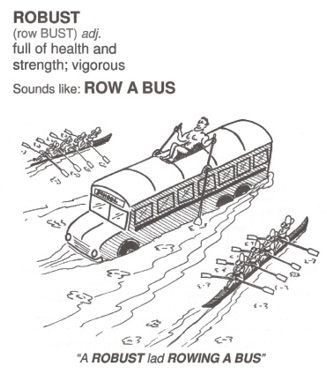

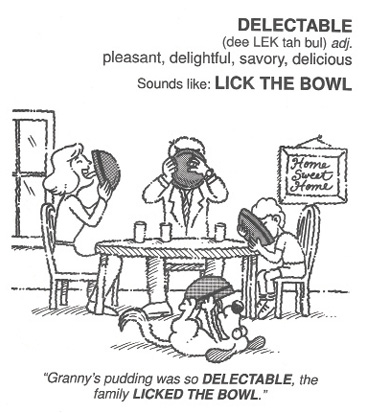

Prior to my hallway intervention with the children, I placed a vocabulary cartoon on my intervention room door. The vocabulary cartoons were created and published by Max, Bryan, and Sam Burchers (1998). I obtained permission to use the cartoons for this study (and any resulting publications). While many of them are geared toward an older audience, I selected 10 with images and words that I felt were appropriate for first graders, based on my experience working with this age group. These cartoons featured the words robust, collide, belittle, fret, compatible, miniscule, delectable, perturb, inhabit, and summit.

While selecting the cartoons, I considered the following questions:

- Which words were appropriate for first graders, and of those, which were the children unlikely to have been exposed to?

- Which keyword rhymes in the cartoons would be relatable to the students?

- Which cartoons would capture their attention?

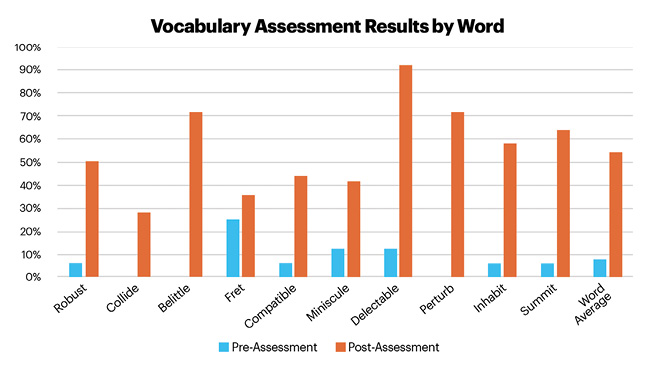

After choosing vocabulary cartoons that I thought would stimulate curiosity and conversation, I created and administered a pretest to determine whether the vocabulary words selected for the intervention were familiar to the students. Scores for the eight students ranged from zero to 20 percent, with an average of 8 percent. These results assured me that students had little exposure to the vocabulary words to be used in the intervention.

To deliver the hallway intervention, I discussed a featured vocabulary word with the children as I escorted them from their first-grade classrooms to the intervention room. At the door of the intervention room, we paused briefly to view the cartoon and discuss it as a group. The hallway vocabulary conversation took no longer than two minutes per group each day. I changed the vocabulary cartoon every third school day until all 10 vocabulary words had been introduced.

Throughout the 30-day hallway intervention, I documented the students’ comments and behaviors (indicating a positive or negative response) to the vocabulary intervention. (For a sample, see “Field Notes: April 9, 2015,” below.) Following the final vocabulary cartoon, I readministered the vocabulary assessment as a posttest. I also interviewed the children and their teachers to gather their feedback on the cartoons and the intervention. During the data analysis phase of the study, I looked for patterns or common themes revealed by cross comparison of the data.

Field Notes: April 9, 2015

I asked students to identify their favorite and least favorite cartoons Their comments gave me insight about their level of understanding.

Which cartoon is your favorite?

S1: Summit, because they have a flag of the United States and you get to climb a mountain!

S3: Inhabit, because the rabbit is staring at the TV! It’s funny!

S4: Inhabit, because I like the bunny in the chair like I like to relax.

Which cartoon is your least favorite?

S4: Miniscule, because I don’t like the eyeball up close.

S5: Robust. I don’t like the man on top of the bus because he looks like naked, bare.

S6: Belittle, because people are being mean to you.

Findings

Finding 1: All eight of the students indicated that the vocabulary cartoons were engaging, and they expressed interest in continuing the intervention.

Based on my field notes and student interviews, there were 42 positive and 17 negative comments and student reactions. The children unanimously reported enjoying the vocabulary cartoon intervention and expressed interest in continued participation. The humor inherent in the approach seemed to be an essential feature.

Humor was intended to be a strong element of the intentional hallway conversations. It often worked well but not perfectly. The day after introducing robust, for example, the children and I walked down the hall and discussed who we thought was so robust that they could “row a bus.” Most students thought our weight-lifting principal was the most robust person in the school. As we neared my intervention room, we flexed our muscles and asked each other if we could “row the bus.” Children couldn’t help but giggle when my jaw dropped in awe of their tiny biceps, and I pointed to the man in the cartoon and asked, “Is that you?!” While the cartoon seemed effective overall, I noted that some children were slightly embarrassed by the cartoon character’s naked chest and tiny swimsuit. Given the media exposure most students experience in their daily lives, I didn’t expect them to be uncomfortable with the cartoon man’s torso. I would definitely provide the cartoon man with a T-shirt and shorts for future interventions.

Sometimes it was not possible to begin the hallway intervention with humor. The day I introduced the cartoon for perturb, a Spanish-speaking student was crying when I arrived to escort his group to my room. He was upset because no one understood what he was saying during recess. After listening to his story, I said, “You’re upset, I can tell! Another word for being upset is perturbed. Come look at the cartoon on my door. This boy disturbed the hornets by throwing a rock at their nest. The hornets got perturbed! What do you think happened?” The students looked at the cartoon and squealed, “They’re gonna sting him!” By this point, everyone was laughing (including the previously distraught student) as we entered the intervention room.

Sometimes, humor was completely absent. Two children did not enjoy the cartoon for belittle. They had been receiving bullying prevention training in their classroom and were upset about the situation in the cartoon. Their empathy for the little boy who was being belittled was passionate. I realized at-risk readers could possibly relate more readily to this particular cartoon character due to personal experience. The cartoon was supposed to be funny and make learners smile. It was disconcerting for the students, and for me as their teacher, when they perceived it as negative. The children’s emotional reaction to the cartoon provided a teaching opportunity to reinforce our school’s position on bullying.

Sometimes, humor was completely absent. Two children did not enjoy the cartoon for belittle. They had been receiving bullying prevention training in their classroom and were upset about the situation in the cartoon. Their empathy for the little boy who was being belittled was passionate. I realized at-risk readers could possibly relate more readily to this particular cartoon character due to personal experience. The cartoon was supposed to be funny and make learners smile. It was disconcerting for the students, and for me as their teacher, when they perceived it as negative. The children’s emotional reaction to the cartoon provided a teaching opportunity to reinforce our school’s position on bullying.

While humor can be hit-or-miss, the children seemed to consistently enjoy the rhymes and the feeling of the words on their tongues. For instance, they would say “rabbitinhabit” with obvious enthusiasm. Students enjoyed imagining themselves as characters in a silly cartoon. For example, the cartoon for the word delectable uses the key phrase “lick the bowl.” It portrays a family, including their dog, at the dinner table, all licking the last bit of pudding from their bowls. The students relished how it felt to say the word delectable and were particularly entertained by the idea of their own families in a similar situation.

Overall, students enjoyed cartoons that featured harmless animals, excitement, and silly situations. The children seemed to look forward to the cartoons. I met one of the students in the hall and told him, “I have a new cartoon today.” He replied, “I know, I saw it when I came to school!” I noticed that the older reading intervention students, who were not participants in the study, were also interested in the cartoons.

Finding 2: The vocabulary assessment revealed improved vocabulary knowledge.

The students’ scores improved from an average of 8 percent on the pretest to 58 percent on the posttest. While I had hoped for better results on the posttest, I found these results promising for a brief and light-hearted intervention.

Based on my observations, the vocabulary words students scored well on were not surprising. Robust, belittle, delectable, and perturb were all words that they had connected to emotionally.

The words the children did not score well on were surprising, at first. But on reflection, I realized I had not taken common first-grade articulation difficulties into consideration. For example, fret was often misconstrued as threat by first graders who could not articulate the /th/ sound yet. As one student put it, “My brother frettened me!” Miniscule was difficult for many of the first graders to say; they seemed more focused on trying to pronounce it than on understanding its meaning.

I cannot explain why students didn’t score well on the word collide. At recess, I have often observed students “collide on the slide,” and have gone over the playground rule specifying “only one student on the slide at a time” many times. I felt certain the cartoon would be relatable to them, so the low scores for collide puzzled me.

Finding 3: Interviews with teachers indicated that the children did not use the vocabulary words independently during classroom interactions. However, teachers supported continuing the cartoon intervention.

I anticipated that students might not spontaneously use the vocabulary words in their classrooms. For first graders to use newly introduced, uncommon words in teacherdirected classrooms would be atypical, particularly since the teachers did not use or hold students accountable for the words. Since none of their classmates had participated in vocabulary intervention, the children’s only exposure to the new words was during our hallway conversations.

Even though students did not independently use the new words in the classroom, teachers viewed the cartoons as positive and supported future implementation of the vocabulary intervention. One teacher suggested that I create cartoons to support student learning of vocabulary words common to standardized tests. Several comments indicated that teachers would have felt more ownership of the vocabulary intervention if they participated in selecting the words, and they would likely reinforce the use of those words in the classroom.

My colleagues’ feedback had a lot of merit. For future interventions, I would collaborate with teachers on selecting cartoons for words that they viewed as most helpful to the children and that they would be more likely to reinforce. For this intervention, I had selected vocabulary cartoons from Burchers’ book rather than develop them myself, because I’m not an artist. In addition, I believed using words that students were not required to learn would help preserve the casual social exchanges the students enjoyed.

Implications

While the improvement in the children’s vocabulary scores suggests that mnemonic vocabulary cartoons can be used to help students learn new words during transition times, the cartoons provided only an introduction to those words. Using new words confidently and appropriately requires deep processing of words, such as understanding and using words in varied contexts and interacting with their meanings (Stahl & Fairbanks 1986). Similarly, studies of vocabulary acquisition have found that children “responded to instruction that required them to make decisions about the appropriateness of contexts for newly learned words, develop uses for new words, and explain why uses made or did not make sense” (Beck & McKeown 2007, 264). So, while students enjoyed the conversations about the cartoons and gained some introductory vocabulary knowledge of the new terms, they didn’t acquire deep understanding of the words’ full range of uses.

As the study progressed, I wondered if the children’s gains in vocabulary knowledge were obtained primarily from features of the vocabulary cartoons or if they were largely a result of our conversations. I realized that the conversations the students and I were having provided a natural opportunity for language modeling and challenged students to think critically about the words’ meanings. The vocabulary cartoons were an intriguing focal point for stimulating student curiosity, social interaction, humor, and play with language. They offered a platform for effective teaching strategies, such as modeling advanced language, providing feedback, and encouraging natural communication that uses a variety of words to connect ideas (Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre 2007). The intervention I had intended for increasing vocabulary knowledge also set the stage for meaningful interaction with me and among the children.

In hindsight, if I had posted cartoons in many areas of the school, there would have been more opportunities for the exchange of ideas as students took notice of them while they waited in the lunch or bathroom lines. I could have asked teachers and other school employees to use the vocabulary cartoons to engage students in conversations and to acknowledge students’ efforts to use the vocabulary words. Merely asking teachers to record children’s use of the words did not incorporate the power of collaboration. Also, I could have structured the pretest to help the children see that they had an opportunity to learn, rather than forcing them to admit “I really don’t know” several times in a row to establish that they had little knowledge of the vocabulary words presented. In the future, any assessments I create will be carefully designed to help students feel positive about learning.

This action research study made me realize that we must use humor responsibly. Humor can be an unwieldy tool. “Individual children do not always find the same situations as funny. An attempt to jest can be highly embarrassing, anxiety provoking, or hurtful when the laughter is directed at them, not with them” (Smidl 2014, 13). Not all of us are adept at using humor, particularly when considering the various individual and cultural differences among children, which can lead to differences in what is perceived as humorous. However, research may be able to help teachers find ways to use humor appropriately with children.

After a decade of teaching primary students, I believed I understood this age group pretty well. The discoveries revealed by this study humbled me into acknowledging I have only scraped the surface in my knowledge of children, how they learn, and how to teach them. Realizing that my knowledge is miniscule motivates me to pay closer attention to how children find magic in playing with language. Further research is needed to examine the potential of using vocabulary cartoons as an intervention method to help children gain vocabulary knowledge and build language through conversations.

References

Beck, I.L., & M.G. McKeown. 2007. “Increasing Young Low-Income Children’s Oral Vocabulary Repertoires through Rich and Focused Instruction.” The Elementary School Journal 107 (3): 251–71.

Burchers, S., B. Burchers, & S. Burchers. 1998. Vocabulary Cartoons: Word Power Made Easy. Punta Gorda, FL: New Monic Books.

Cain, K., & J. Oakhill. 2011. “Matthew Effects in Young Readers: Reading Comprehension and Reading Experience Aid Vocabulary Development.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 44 (5): 431–43.

Condus, M.M., K.J. Marshall, & S.R. Miller. 1986. “Effects of the Keyword Mnemonic Strategy on Vocabulary Acquisition and Maintenance by Learning Disabled Children.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 19 (10): 609–13.

Cunningham, A.E., & K.E. Stanovich. 1991. “Tracking the Unique Effects of Print Exposure in Children: Associations with Vocabulary, General Knowledge, and Spelling.” Journal of Educational Psychology 83 (2): 264–74.

Ivy, L.L. 2013. “Using Humor in the Classroom.” Journal of Adventist Education 75 (3): 39–43. http:// circle.adventist.org/files/jae/en/jae201375033905.pdf.

Lervåg, A., & V.G. Aukrust. 2010. “Vocabulary Knowledge Is a Critical Determinant of the Difference in Reading Comprehension Growth between First and Second Language Learners.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 51 (5): 612–20.

Lombardi, T., & G. Butera. 1998. “Mnemonics: Strengthening Thinking Skills of Students with Special Needs.” The Clearing House 71 (5): 284–86.

Mastropieri, M.A., T.E. Scruggs, & B.J. Fulk. 1990. “Teaching Abstract Vocabulary with the Keyword Method: Effects on Recall and Comprehension.” Journal of Learning Disabilities 23 (2): 92–107.

National Reading Panel. 2000. Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. Report of the National Reading Panel. www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf.

Pianta, R.C., K.M. La Paro, & B.K. Hamre. 2007. Classroom Assessment Scoring System: Manual Pre-K. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Slavin, R.E., C. Lake, B. Chambers, A. Cheung, & S. Davis. 2009. “Effective Reading Programs for the Elementary Grades: A Best-Evidence Synthesis.” Review of Educational Research 79 (4): 1391–466.

Smidl, S.L. 2014. “My Daddy Wears Plucky, Ducky Underwear: Discovering the Meanings of Laughter in a Preschool Classroom.” Voices of Practitioners 9 (1): 1–16. www.naeyc.org/files/naeyc/images/voices/11_Smidl%20v9-1.pdf.

Stahl, S.A., & M.M. Fairbanks. 1986. “The Effects of Vocabulary Instruction: A Model-Based Meta-Analysis.” Review of Educational Research 56 (1): 72–110.

Weimer, M. 2011. “Humor in the Classroom: 40 Years of Research.” The Teaching Professor 25 (10): 3.

Wolgemuth, J.R., R.B. Cobb, & M. Alwell. 2008. “The Effects of Mnemonic Interventions on Academic Outcomes for Youth with Disabilities: A Systematic Review.” Learning Disabilities: Research and Practice 23 (1): 1–10.

Photographs: pp. 64 (right), 66, courtesy of the author; pp. 70, 71, © iStock; pp. 64 (left), 68, 69, 71, courtesy of Burchers et al. and by permission of New Monic Books

Heidi Heath DeStefano, MEd, has taught kindergarten and first grade and is currently a Reading Recovery teacher at Pronghorn Elementary, in Gillette, Wyoming. [email protected]