“There’s a Hole in the Tree!” Kindergartners Learning in an Urban Park

You are here

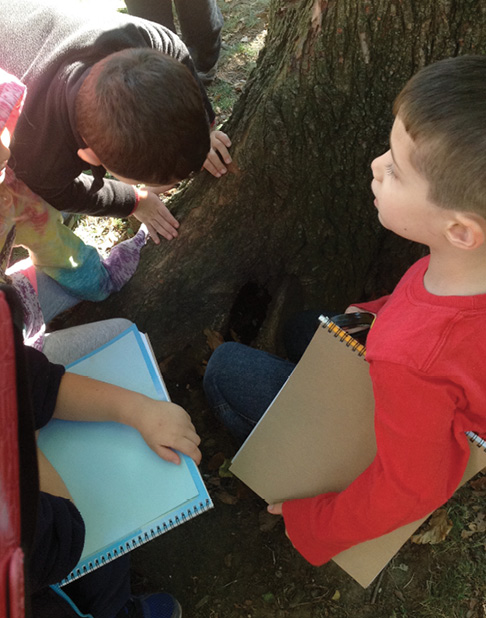

On a crisp October visit to a local park, half of my kindergarten class gathers around a tree. Some children use magnifying glasses to peer into a hole in the tree while others prod the hole with sticks and branches. I get closer to the children so I can hear their conversations and ask what has attracted their attention.

“We found a big hole in the tree,” Aiden says.

“There are worms and spiders in there,” Ella replies.

I ask the children what else they think might be living inside the tree and am met with enthusiastic replies: “Honeybees!” “Ladybugs!” “Caterpillars!” “Termites!” the children shout excitedly.

This snapshot of my kindergarten class comes from the second Friday in a row in which we visited a park several blocks from our school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The children live in nearby apartment buildings and most do not have access to nature on a daily basis. To expose them to nature and to practice environmental stewardship, I chose an area in the park for us to observe and explore on most Friday mornings throughout the school year. Armed with clipboards, pencils, and paper, we walked to the park with the assistance of several parent volunteers. On the morning described in the vignette, I was excited that the children had discovered something that was interesting enough to them to spark a whole-class, long-term inquiry.

This snapshot of my kindergarten class comes from the second Friday in a row in which we visited a park several blocks from our school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The children live in nearby apartment buildings and most do not have access to nature on a daily basis. To expose them to nature and to practice environmental stewardship, I chose an area in the park for us to observe and explore on most Friday mornings throughout the school year. Armed with clipboards, pencils, and paper, we walked to the park with the assistance of several parent volunteers. On the morning described in the vignette, I was excited that the children had discovered something that was interesting enough to them to spark a whole-class, long-term inquiry.

Bringing the great outdoors to children

Learning about nature while in nature is a priority for me as an educator. Luckily, the school administration allowed us to enrich our curriculum by visiting the park regularly. I felt fortunate because many other public schools across the United States have significant barriers preventing teachers from conducting outdoor learning in nature. Due to the pressures of standardized testing and increased demand for (and perhaps misunderstanding of) instructional rigor in many schools, time spent outside is at a premium. Far too many children only go outside for recess, the duration of which varies from school to school (Ramstetter & Murray 2017). Additional barriers include a lack of natural outdoor spaces within walking distance and concerns about weather, safety, and supervision (Ernst 2014).

But even when they are not in school, children tend to spend little time in nature. For families, issues that keep their children inside range from parental fears about strangers and crime to busy schedules packed with indoor activities; large amounts of time devoted to computers and video games are also a troublesome factor (Spencer & Blades 2006).

Researcher Richard Louv coined the phrase “nature-deficit disorder” when referring to the perils of children’s alienation from nature. In an interview in The American Journal of Play (Louv & Charles 2011), Louv examined the disparities between the rich outdoor experiences of prior generations and the decline in today’s outdoor play opportunities. Noting general apathy toward nature, he asked, “Where will future stewards of the earth come from?” (138).

Authentic learning experiences for the mind and body

Exploring the natural world provides rich, authentic learning experiences. Outdoor learning offers young children opportunities to ignite their creativity and imaginations, as well as cultivate problem-solving skills (Kiewra & Veselack 2016). For example, during one of our visits to the park, a question arose about the height of our special tree. The children wanted to know how high the tree went into the sky and debated the best way to find the answer. Their theories ranged from finding a very tall ruler to stacking one child on top of another until they reached the top of the tree. Although the children’s interest shifted to other aspects of the tree fairly quickly, in each visit to the park our time and space outdoors afforded our class opportunities to imagine, wonder, and develop a great variety of ideas together.

Outdoor learning gives teachers the tools they need to set the stage for active learning and hands-on interaction with living things. Instead of children passively observing a science experiment conducted by the teacher, children can more fully engage in the inquiry process of observing, posing questions, investigating, and making exciting discoveries of their own (Basile & White 2000).

Research also shows a correlation between exposure to nature and reduced stress levels for children (Chawla 2012; Nedovic & Morrissey 2013). In my classroom, I have noticed that the children who demonstrate the most difficulty sitting still or completing required tasks indoors often flourish in the more relaxed, open space of the outdoors, where they have ample opportunities to interact with their environment. In fact, one study found that children living in urban areas who spent more time exploring nature exhibited greater resilience and were better equipped to handle adversity in their everyday lives (Corraliza, Collado, & Bethelmy 2017).

Promoting environmental stewardship

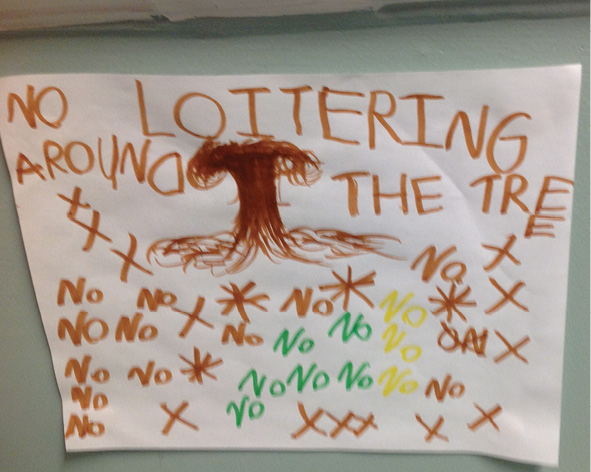

Engaging young children in hands-on activities in which they interact with and observe the plants and animals in their communities helps them gain respect for the environment. These special experiences help foster environmental stewardship and a willingness to protect and preserve the living and nonliving natural elements in their worlds (Jacobi-Vessels 2013). As I noticed the children’s interest in tree preservation growing, I looked for additional ways to involve them in environmental social action opportunities. For example, I reached out to an organization called MillionTreesNYC, whose mission is to promote stewardship across the five boroughs of New York City and to improve the quality of urban life. The organization encourages people citywide to plant or adopt and care for trees. An educator from the organization visited our classroom and shared ways we could help preserve the trees growing on our school’s block. Our class picked a tree in front of the school to adopt, and the educator showed us how to mulch and water the soil and to pick weeds. As part of the MillionTreesNYC initiative, he also provided our class with gardening tools, such as watering cans, gardening gloves, and small rakes and shovels. The children constructed signs to hang across a gate protecting the tree; their signs asked others to respect the tree and keep the area around it clean.

The class tree adoption—coupled with our visits to the nearby park—helped to bring the children’s interest in tree preservation to life: they felt a responsibility to care for our newly adopted tree as well as a personal connection to our tree in the park. The children wanted to ensure that the animals living in the hole in our park tree were able to continue using it as their home.

At the time of this inquiry, I was reading Laurie Rubin’s book, To Look Closely: Science and Literacy in The Natural World (2013). I noticed a strong parallel between her work with her rural second grade classroom and the work happening in my urban kindergarten classroom. Rubin describes how the discovery of pollution in a stream that her second-graders visited caused an uproar among the children, and they acted swiftly to alert local authorities. The children’s feelings of deep respect and admiration for their natural environment developed from time devoted to nature study in the curriculum and their teacher’s passion for “creating stewards to protect the future health of our planet” (214). Rubin’s work greatly inspired me to keep the thread of environmental stewardship running through my kindergartners’ daily activities, routines, and discussions.

Bringing outdoor learning to urban school communities

It can be challenging to bring nature-focused outdoor learning to children in urban school communities. Urban schools are often associated with a lack of outdoor space—or at least a lack of natural space—around or near the school facility (Basile & White 2000). The benefits of outdoor learning can induce teachers to look for nature in the recess yard or on a neighborhood walk and to familiarize children with everyday natural sights in an urban setting, such as pigeons, squirrels, and worms (Jacobi-Vessels 2013).

Children growing up in urban areas benefit from tending gardens, visiting parks, and observing animals in their schools and neighborhoods. It is important for community members to advocate for children in order to champion ideas such as planting trees, creating more green spaces, and finding more play opportunities for children in nature (Chawla 2012).

Studying the hole in the tree

Our conversation about the hole in the tree followed us back to the classroom. During choice time the following week, the children drew pictures of animals that could live inside the hole in the tree. We visited the hole two more times in October to further investigate. The children sketched images of the parts of the tree, including the large hole, which was located in the middle of the tree, just low enough for the children to look directly into it. The children were already familiar with tree vocabulary (such as trunk, roots, branches, and leaves) from previous science instruction. Their conversations included these scientific words as they described their findings during their observations of the tree.

The children ran their hands over the bumpy bark and balanced their feet on top of the tree’s exposed roots. They commented on which sections of the tree felt smooth versus bumpy, or soft versus scratchy. During a morning meeting (prior to walking to the park), our discussion focused on which scientific tools may help us gather more information about the hole in the tree, and these were the items we selected to bring with us to the park. The children handled these tools (magnifying glasses, flashlights) to closely study the hole in the tree. Some children reported seeing spiders and termites, while others saw and felt mounds of dust and dirt. They collected treasures they found nestled beside the tree, such as leaves, twigs, rocks, and broken bits of bark, and brought them back to the classroom. A group of children decided to re-create the tree in our classroom; they made animals and insects using recyclables, construction paper, paint, and other art materials. As they worked, they compared the class tree to a photograph I had taken of the tree in the park, and to their sketches of the tree.

Our tree inquiry began to take center stage in the classroom and intertwine with our social studies unit on communities. Our visits to the park became an extension of our school and neighborhood communities, and the class developed an awareness of how integral trees are to the environment. As we charted why they are important to a community, several children referenced the holes in trees as hiding places or homes for animals. I chose to build on the children’s curiosity about animals that live in or rely on trees and purposefully added new books and read-alouds about animals and their habitats to our fall library collection.

One book in particular, The Great Kapok Tree: A Tale of the Amazon Rain Forest, by Lynne Cherry, sparked a rich discussion as children made connections between the significance of the Amazon Rain Forest and the tree in our park. The children asked questions about the book, such as why the woodsmen wanted to cut down the kapok trees. They showed concern for the animals and insects that would lose their homes if the trees were chopped down. I showed the children images of the deforestation happening in the Amazon; everyone agreed that we must do something to help others understand that trees are important for animals and must be preserved.

When I asked the children how we could spread our message throughout the school, several children proposed putting on a puppet show using the animals they had made for the class tree. However, further discussion uncovered problems with using the puppet theater—most notably a lack of space for all of the children to have a role in the show. I asked the children if it would be possible to act out the show without using the puppet theater. Could they create the characters with their own bodies, using the classroom meeting rug as our stage?

From my perspective, this was a great opportunity to tie our learning about trees, animals, and habitats to another experience the children had recently had—watching a play at Lincoln Center. The children were familiar with such theater terms as characters, setting, costumes, and props. By developing their own play, they would come to understand these concepts more deeply. Excited by the idea of putting on their own play, the children started calling out which parts they wanted to have in the show. We were on our way.

A show is born

The class play, inspired by The Great Kapok Tree, was titled “A Tree for All the Animals.” We began planning the play by brainstorming the different characters we wanted to include; our class read-alouds about the different living things in the rain forest offered children many choices as to which animal or insect they wanted to play. Each child listed the three roles he or she would feel comfortable playing, and I assigned parts based on the children’s preferences. They wrote their own dialogue, with support from my colleagues (an assistant teacher and a student teacher) and me, as we met in small groups during our literacy centers and choice time over three days. By the end of the week, the characters in the play consisted of three woodsmen and various animal groups: bees, butterflies, ladybugs, tigers, rabbits, monkeys, and sloths. Once our script was written, rehearsals could begin.

Family engagement played a large part in the play’s development. Families were familiar with our nature outings and our tree inquiry through reading our classroom blog, which I updated weekly. I reached out to families, asking if they would volunteer as chaperones during our trips to the park. I also encouraged families to send in materials to aid in the costume and prop making for the show, such as fabric scraps, papers with different textures (cardboard boxes, leftover wrapping paper), and loose parts they could find around their households (bottle caps, clothespins). All of the children were sent home with a copy of the script so they could practice their lines with their families. And all families were invited to the show to celebrate the process and the culmination of all the children’s hard work.

The children created their own face masks out of paper plates, and everyone helped paint a mural of a rain forest to use as a backdrop for the play. The children playing the woodsmen assembled axes out of tin foil, duct tape, and other craft materials available in the classroom. On the day of the performance, the children wore colors that matched those of the animals or insects they were portraying. I took on the role of the narrator, reading the script the children had written and pausing at key moments for the children to deliver their lines.

A buzz of excitement fills the air as family members take their seats to watch the children’s play, “A Tree for All the Animals.” The children have decorated the hallways with posters advertising the performance and advocating for the protection of trees.

The children start to pull their handmade paper plate masks over their faces. I watch a swarm of animals gather around the rug. The three woodsmen stand in the center of the rug and point to the tree the class has constructed. As they pantomime pulling back their axes to cut it down, an impassioned protest begins:

Butterfly: Why are you going to cut down our tree? We live here and this is our home.

Bumblebee #1:Bzzz . . . if you chop down my tree, where will I get my honey?

Bumblebee #2:

Bzzz . . . if you cut down this tree, how will I breathe?

Rabbit: Don’t cut down my tree! I like to hide in the hole.

Each of the 22 animals explains the value of the tree. At the end of the play, the three woodsmen—moved by the animals’ reasoning—decide not to cut down the tree after all. The children bow amidst cheerful audience applause.

The tree inquiry, stemming from outdoor learning in a neighborhood park, not only created lasting learning for the children but inspired them to care about and respect trees, planting the seeds for future nature lovers and stewards.

References

Basile, C., & C. White. 2000. “Respecting Living Things: Environmental Literacy for Young Children.” Early Childhood Education Journal 28 (1): 57–61.

Chawla, L. 2012. “The Importance of Access to Nature for Young Children.” Early Childhood Matters 118: 48–51.

Corraliza, J.A., S. Collado, & L. Bethelmy. 2017. “Effects of Nearby Nature on Urban Children’s Stress.” Asian Journal of Environment-Behaviour Studies 2 (3): 37–46.

Ernst, J. 2014. “Early Childhood Educators’ Use of Natural Outdoor Settings as Learning Environments: An Exploratory Study of Beliefs, Practices, and Barriers.” Environmental Education Research 20 (6): 735–52.

Jacobi-Vessels, J.L. 2013. “Discovering Nature: The Benefits of Teaching Outside of the Classroom.” Dimensions of Early Childhood 41 (3): 4–10.

Kiewra, C., & E. Veselack. 2016. “Playing with Nature: Supporting Preschoolers’ Creativity in Natural Outdoor Classrooms.” The International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 4 (1): 70–95.

Louv, R., & C. Charles. 2011. “Battling the Nature Deficit with Nature Play: An Interview with Richard Louv and Cheryl Charles.” American Journal of Play 4 (2): 137–49.

Nedovic, S., & A.-M. Morrissey. 2013. “Calm Active and Focused: Children’s Responses to an Organic Outdoor Learning Environment.” Learning Environments Research 16 (2): 281–95.

Ramstetter, C., & R. Murray. 2017. “Time to Play: Recognizing the Benefits of Recess.” American Educator 41 (1): 17–23.

Rubin, L. 2013. To Look Closely: Science and Literacy in The Natural World. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Spencer, C., & M. Blades, eds. 2006. Children and Their Environments: Learning, Using and Designing Spaces. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Photographs: courtesy of the author

Melissa Fine, MA, is an instructional coordinator for the Division of Early Childhood Education in Queens, New York. Melissa supports teachers, program leaders, and children in universal 3K and pre-K programs. She has worked as an early childhood educator for over 10 years. She has published several works for NAEYC and Young Children focused on celebrating the interests of children and advocating for developmentally appropriate practices. [email protected]