Our Proud Heritage. Sowing the Seeds of Hope for Today: Remembering the Life and Work of Susan Blow

You are here

With all 50 states and the District of Columbia facing public education funding issues, and with less than half of 4-year-olds in publicly funded preschool settings (US Department of Education 2015), it is time to recommit ourselves to the future of our country’s children and to advocate for universal access to high-quality, publicly funded early childhood education. There’s a perfect parallel for the situation we are facing today. It happened over 140 years ago, in St. Louis, Missouri.

Setting the stage

In the late 1700s, Johann Pestalozzi (1746–1827), often considered the “Father of Elementary Education,” set the stage for kindergarten when he developed lessons for under-served young children in Switzerland. Pestalozzi favored using real objects to teach with, rather than merely words (as some would say, “things before words”). He called for originating sensory experiences with nature using objects, such as pebbles and rocks for mathematics instruction, and championed parent education in his writings, such as How Gertrude Teaches Her Children (1898). He believed that learning should include the involvement of the “hand, head, and heart,” an early forerunner to current concepts of child development (Wolfe 2002, 62)

Friedrich Froebel (1782–1852), the “Father of Kindergarten,” studied under Johann Pestalozzi in Switzerland for about two years. After returning home to Germany, Froebel founded an elementary school in 1817. To reach younger children, Froebel dreamed of a totally new concept, which he called “kindergarten,” meaning “children’s garden.” Using play as his methodology, in 1839 he founded the first kindergarten for children ages 3 to 6 (Moore 2002).

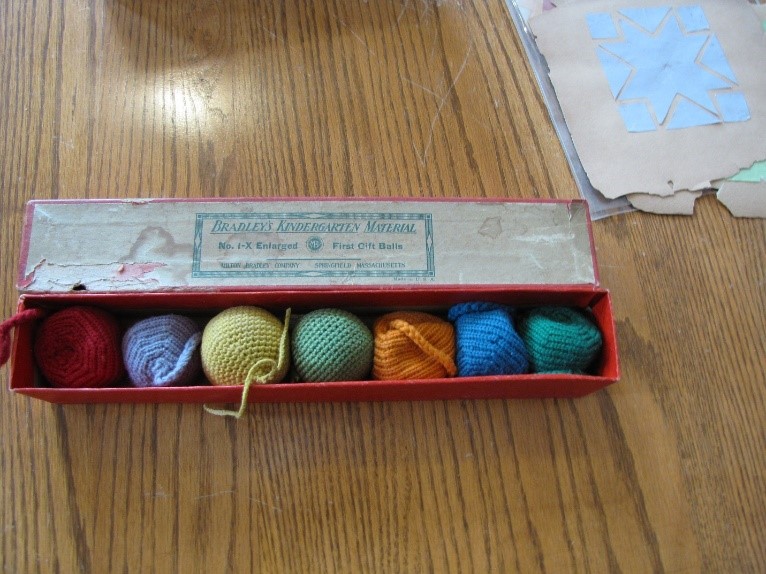

Using the object-focused approach to lesson planning he had learned from Pestalozzi, Froebel established a system of educational materials, or “gifts,” that teachers gave to the kindergartens. These gifts included colored yarn balls, wooden shapes, a series of graduated blocks, and other open-ended materials for learning (see, “A Look at Froebel’s First Three Gifts”). Froebel then added finger plays, creative songs, circle time, gardening, and many other playful activities to inspire young children. Froebel’s other novel approach was to train female teachers, who were overlooked in the educational world at that time. Froebel’s concept of kindergarten quickly spread across Europe and eventually around the world (Moore 2002).

In the United States, the earliest kindergartens were private, and classes were often conducted in the teachers’ homes. Kindergarten teachers, many of whom were women, usually found students through word of mouth or via discrete newspaper advertisements, developing a clientele who could pay for their children’s learning. Thanks to the advocacy and leadership of Susan Blow (1843–1916), many more children soon had access to kindergarten. Often called the “Mother of the Public Kindergarten Movement,” Blow established a rich legacy of public school kindergartens throughout the United States.

A life’s work

Susan Elizabeth Blow was born on June 7, 1843, in St. Louis, and grew up in a community of both ethnic and religious diversity. Born into a life of privilege, Susan received the best education available. She attended a variety of schools open to girls at the time—a French school, various local schools, and a finishing school in New York—and was also educated at home by governesses and teachers hired by her father, who also opened his extensive library to her use (Shepley 2011). (Also noteworthy: Susan’s uncle, Taylor Blow, is credited with freeing Dred Scott and his family from slavery in 1857. Later, her father, Henry Blow, paid for Scott’s burial.)

![]() At a young age, Blow subscribed to the teachings of the Bible and became a skilled Sunday school teacher at the Carondelet Presbyterian Church, an experience that led her to choose teaching as a profession (Menius 1993). Blow became aware of Froebel’s invention of kindergarten while touring Europe in 1871, when she had the opportunity to observe one of Froebel’s schools in Germany; upon returning home, she continued to learn everything she could about this new German approach to education (Menius 1993). She also visited William Torrey Harris (1835–1909), the St. Louis superintendent of schools, to discuss the feasibility of starting a kindergarten program in the local public school system. Harris, already concerned about the younger children of St. Louis, encouraged Blow to prepare to teach kindergarten. In 1871–72, she received her preparation at the New York Institute for Kindergarteners (Tharp 1988). Because of Blow’s high standing in the community, Harris appointed a committee to consider the possibility of a kindergarten program. After studying the venture’s merits, the committee decided in favor of opening such a program.

At a young age, Blow subscribed to the teachings of the Bible and became a skilled Sunday school teacher at the Carondelet Presbyterian Church, an experience that led her to choose teaching as a profession (Menius 1993). Blow became aware of Froebel’s invention of kindergarten while touring Europe in 1871, when she had the opportunity to observe one of Froebel’s schools in Germany; upon returning home, she continued to learn everything she could about this new German approach to education (Menius 1993). She also visited William Torrey Harris (1835–1909), the St. Louis superintendent of schools, to discuss the feasibility of starting a kindergarten program in the local public school system. Harris, already concerned about the younger children of St. Louis, encouraged Blow to prepare to teach kindergarten. In 1871–72, she received her preparation at the New York Institute for Kindergarteners (Tharp 1988). Because of Blow’s high standing in the community, Harris appointed a committee to consider the possibility of a kindergarten program. After studying the venture’s merits, the committee decided in favor of opening such a program.

Des Peres School, site of the first public kindergarten in the United States, 1873, St. Louis.

In 1873, a kindergarten opened in the new Des Peres School on Michigan Avenue in St. Louis; this was the very first publicly funded kindergarten in America. Blow served as the director and also began training other teachers, including several African American women who became active in the kindergarten movement (Aldridge & Christensen 2013). Blow encouraged continuing learning for her teachers, requiring them to study not only Froebel’s methods but also literature, philosophy of history, and psychology (Fisher 1924). In addition, Blow emphasized education for the mothers of the children enrolled in kindergarten.

The Des Peres kindergarten classroom with original furniture, 1873. Note the Froebel gifts on the tables.

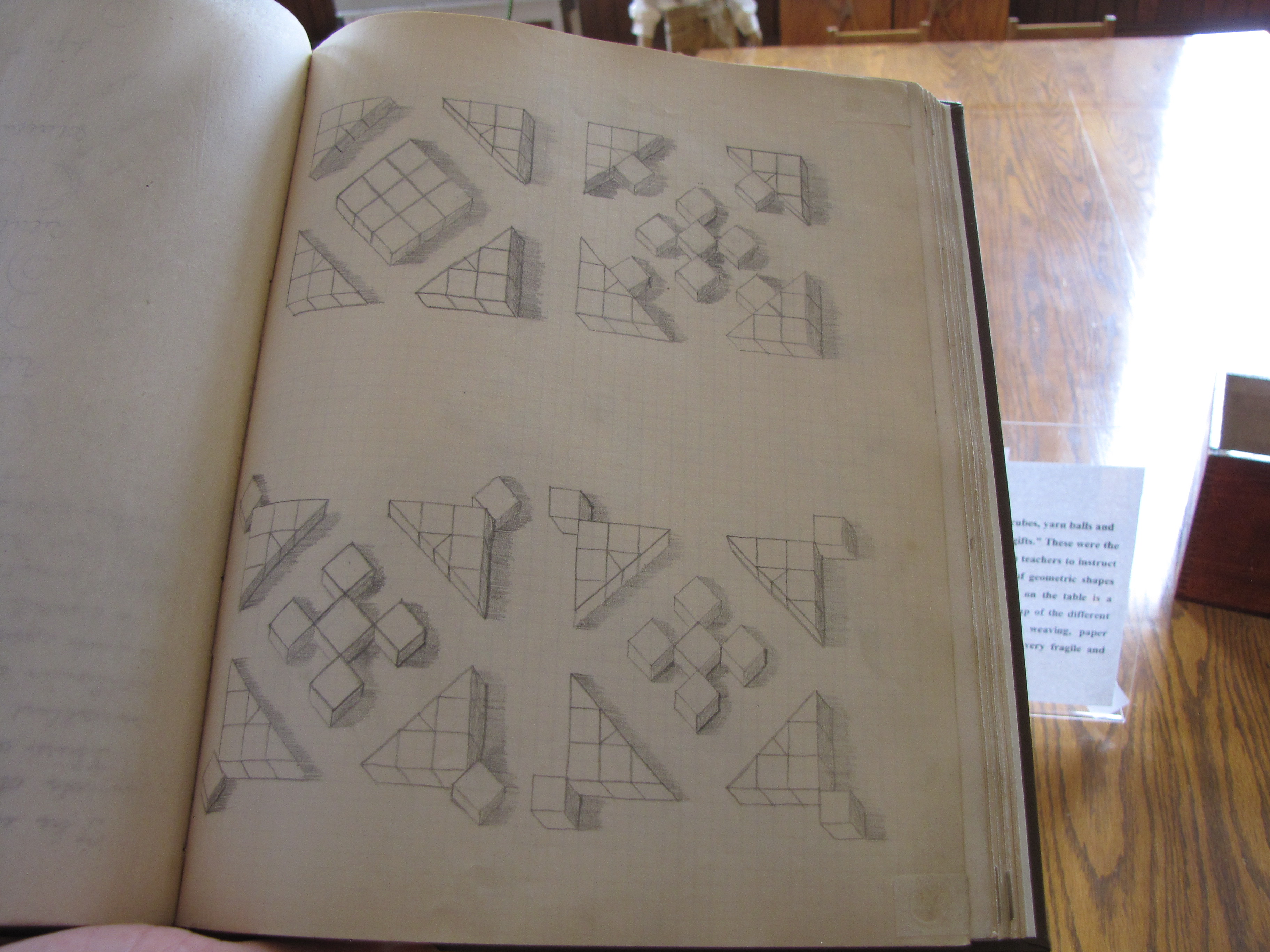

This is a teacher’s lesson plan for block instruction with the Froebel gifts. Susan Blow facilitated the training of all St. Louis public kindergarten teachers from 1873–1903. Professional development in Froebel’s kindergarten methods was essential to the kindergarten’s overall quality.

The public kindergarten program proved popular. In 1875, just two years after the first kindergarten opened, the school board tried to cut costs by eliminating it, but, “1,500 people signed a petition that successfully urged them not to do so” (Shepley 2011, n.p.). By 1880, Blow had helped to start 58 kindergartens in St. Louis, serving over 9,000 children.

Susan Blow continued to advance the kindergarten movement during the remainder of her life, including producing a new edition of The Mottoes and Commentaries of Friedrich Froebel’s Mother Play in 1895, edited by William Torey Harris, who by that time was a dear friend (Blow 1895). In the editor’s preface, Harris writes about Blow’s work on this volume:

This is justly regarded as the key to the philosophy of the kindergarten and as the manual of its practice. Miss Blow has drawn upon all the resources of her experience and study to make this edition a perfect handbook for English-speaking mothers and teachers. (Blow 1895, vii)

Blow’s other works include Symbolic Education (1894), Letters to a Mother on the Philosophy of Froebel (1899), Kindergarten Education (1900), and Educational Issues in the Kindergarten (1908).

In 1903, Susan Blow led the Committee of Nineteen, a group of kindergarten supporters expressing different views on kindergarten but who were all members of the professional organization The International Kindergarten Union (Fisher 1924). Blow would go on to lecture on kindergarten at Columbia University Teachers College from 1905 to 1909 (Lascarides & Hinitz 2011).

Soon, the public kindergarten system Blow founded became a national model for adding early childhood education to public schools across the country.

An inspiring legacy

Susan Blow’s legacy of the public school kindergarten movement still resonates because it is a story of access for all. If Blow were alive today, she would almost certainly be calling for universal early childhood education and subsidized child care. In addition, Blow would remind us that the playful elements of the earliest kindergartens—songs, finger plays, wooden blocks, dramatic play, sand boxes, and more—are essential for learning. Quality kindergartens in public schools with well-trained teachers who inspire playful learning are Susan Blow’s legacy. Her life’s work should remind us all of our need to help every child succeed, starting with an excellent education.

Following in Susan Blow’s footsteps

Here are some ways you can support the call for better funding for early childhood education:

- Understand how your local schools and early childhood programs are funded. Are they recipients of local property tax funds, state funds, federal funds, and/or grants? Are there disparities in amounts of funding across communities?

- Contact your local, state, and federal elected officials. Let these individuals know of your support for better funding for early childhood education. (If you’re not sure who your congressional representative is, whoismyrepresentative.com can help.) Sign up for newsletters or other updates from your elected officials to stay informed and take the time to email, call, or visit your elected officials.

- Register to vote, and vote! And encourage other eligible citizens to register and vote too. Read candidates’ materials to see if they support universal access to high-quality early childhood education.

- Join professional organizations that work to educate both elected officials and the general public. Most professional organizations, such as NAEYC, regularly produce tips and materials to support and engage early childhood education advocates. (For example, see www.americaforearlyed.org.)

A Look at Froebel’s First Three Gifts

Any well-equipped early childhood classroom contains an assortment of materials intentionally designed to allow young children to explore new ideas and learn basic concepts related to math, science, and other content areas. In Froebel’s kindergarten, young children were encouraged to learn through playful activities, including singing songs, planting gardens, and exploring 10 “gifts” that were essentially manipulative sets designed to support curiosity and hands-on learning.

Today’s early childhood professional would be very comfortable working with any one of Froebel’s gifts. Here is a quick look at the first three gifts. How would you use each in your classroom?

Gift one: Six soft yarn balls on strings

For young children, a ball is a familiar toy. These soft balls represent the three primary and three secondary colors. Each ball is itself a complete form, and by using the strings the balls can be combined in various designs. The balls can be swung, rolled, or tossed, and can be used in solitary play or in social play with the teacher or other children.

Gift two: Wooden sphere, cylinder, and cube

These three familiar shapes represent the forms of objects common in a child’s life. While each is complete in itself, the shapes can be used in combination to create new forms. Children can count edges, sides, and corners; they can also work with concepts such as above and below, up and down, front, back, and sides, and so on. Each of these blocks has a hole drilled through it so the shapes can be strung, hung, or combined.

Gift three: The divided cube

In this gift, eight smaller cubes in two layers compose a single larger cube. Young children can use these cubes to learn concepts like part, whole, addition, subtraction, equal to, and many more. The use of the cubes also allows children to create various designs and forms.

References

Aldridge, J., & L.M. Christensen. 2013. Stealing from the Mother: The Marginalization of Women in Education and Psychology from 1900–2010. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Blow, S.E. 1895. The Mottoes and Commentaries of Friedrich Froebel’s Mother Play. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Fisher, L. 1924. “Susan Elizabeth Blow.” In Pioneers of the Kindergarten in America, ed. Annie Laws, International Kindergarten Union, and Committee of Nineteen, 188–94. New York: The Century Company.

Lascarides, V.C., & B.F. Hinitz. 2011. History of Early Childhood Education. New York: Routledge.

Menius, J.M. 1993. Susan Blow: “Mother of the Kindergarten”: Gateway to Education: A Pioneer in Early Childhood Education. St. Clair, MO: Page One.

Moore, M.R. 2002. “An American’s Journey to Kindergarten’s Birthplace.” Childhood Education 79 (1): 15–20.

Shepley, C.F. 2011. “Susan Blow: Bringing Public Kindergarten to the US.” Excerpt from Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery. History Happens Here (blog). Missouri Historical Society. http://mohistory.org/blog/susan-blow-bringing-public-kindergarten-to-the-u-s/.

Tharp, L.H. 1988. The Peabody Sisters of Salem. Boston: Little, Brown.

US Department of Education. 2015. A Matter of Equity: Preschool in America. Washington, DC. www2.ed.gov/documents/early-learning/matter-equity-preschool-america.pdf.

Wolfe, J. 2002. Learning from the Past: Historical Voices in Early Childhood Education. Mayerthorpe, Alberta: Piney Branch Press.

Photographs courtesy of the authors

Mary Ruth Moore, PhD, is professor emerita of education at the University of the Incarnate Word, San Antonio, where she taught early childhood education courses for 23 years and conducted research concerning the history of early childhood education. Prior to her service at UIW, Mary Ruth taught in elementary schools in Kentucky, Indiana, South Carolina, and Texas for 25 years. [email protected]

Constance Sabo-Risley, MA, is the University of the Incarnate Word certification officer and assessment coordinator for students seeking initial certification through the university’s Dreeben School of Education. With Mary Ruth Moore, she edited Play in American Life: Essays in Honor of Joe L. Frost, which was published in 2017. [email protected]