Approaching Interdisciplinary Teaching: Using Informational Texts During Social Studies

You are here

Many young children love learning about their world through informational texts (Mohr 2006; Kraemer, McCabe, & Sinatra 2012), such as books that teach about science and social studies topics; procedural texts like cookbooks and instruction manuals; and resources like maps, timelines, and diagrams. Walk into many primary-grade classrooms today and you are more likely to see students reading, writing, and listening to a variety of informational text types (Donaldson 2011) than was common 20 years ago (Duke 2000). This is due in part to an explicit emphasis on informational text types within the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices [NGA] & Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO] 2010).

As former elementary educators turned literacy coaches, curriculum developers, and researchers working in the field of early literacy for more than 30 collective years, we (the authors of this article) explore how to effectively teach with informational text types in developmentally appropriate ways. Effective methods of teaching with informational texts include using interactive read alouds (Smolkin & Donovan 2003; Heisey & Kucan 2010), pointing out common text structures (Williams 2008), and discussing key vocabulary (Wright 2013). (For more about effective practices for promoting science through informational text read alouds and writing activities, see Finding Time for Science: Using Informational Texts to Increase Children’s Engagement, Knowledge, and Literacy by Jill M. Pentimonti, Hope K. Gerde, and Arianna E. Pikus.)

Replacing some of your readings of stories with informational texts is a fine start, but instruction with informational texts can also occur outside the reading–language arts block (Cervetti & Hiebert 2015). In fact, an interdisciplinary approach using texts for authentic purposes can be more effective to promote disciplinary and literacy learning than traditional curricular models that separate reading and writing from other content areas (e.g., Purcell-Gates, Duke, & Martineau 2007; Vitale & Romance 2011; Cervetti et al. 2012; Halvorsen et al. 2012; Wright & Gotwals 2017; Duke et al., forthcoming). Given that the purpose of informational texts is to teach readers about the natural and social world, science and social studies present a multitude of possibilities for examining informational texts for authentic and engaging purposes, such as using texts to learn about and compare perspectives (e.g., Tschida & Buchanan 2015; Demoiny & Ferraras-Stone 2018). As students listen to and explore multiple informational texts within the context of science and social studies, they build their knowledge base of how the world works (Heisey & Kucan 2010; Cervetti & Hiebert 2015; Strachan 2016). It is this very knowledge base that will enable young learners to comprehend informational texts in the future (Best, Floyd, & McNamara 2008).

Numerous interdisciplinary models uniting science and informational texts are available to teachers (Guthrie, McRae, & Klauda 2007; Vitale & Romance 2011; Cervetti et al. 2012), yet in our experience as researchers, coaches, and teachers, early childhood educators are rarely provided guidance in how to integrate informational texts in meaningful ways within social studies. And social studies instruction may be neglected altogether in the primary grades (Fitchett & Heafner 2010) or positioned as secondary to literacy learning (Pace 2012). This means many missed opportunities to develop critical thinkers prepared to participate as informed citizens of this nation and the world.

Social studies involves much more than learning new content; it includes developing essential literacies too.

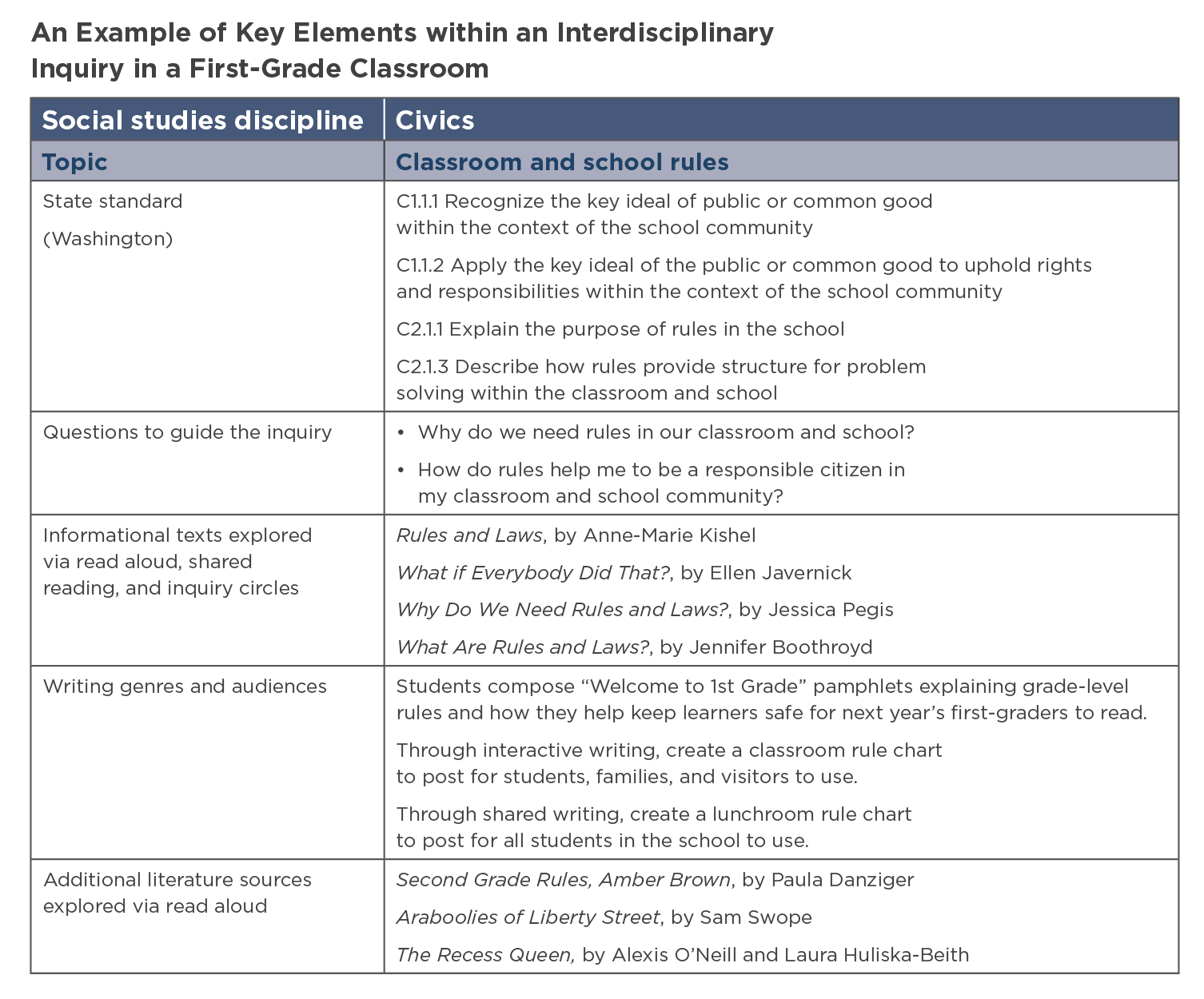

In the following article, we share three principles for teachers of grades 1–3 who wish to attempt or refine an interdisciplinary approach uniting informational text instruction with social studies content. We include many examples of these principles in action throughout the article and we provide an example of key elements within an interdisciplinary inquiry in a first-grade classroom in the table below. These principles are as follows:

- Position inquiry at the center.

- Gather texts with similar and different perspectives for comparison.

-

Provide writing opportunities

to authentic audiences.

These principles will help teachers create a more authentic and motivating environment for informational text exploration while simultaneously building students’ knowledge of the social and natural world and preparing them for an engaged and informed civic life. These three principles are grounded in the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards (NCSS 2013a). The C3 Framework was created to support the teaching of social studies in ways that “prepare young people for effective and successful participation in college, careers, and civic life” (NCSS 2013a, 6), serving as a resource at the state and local levels regarding social studies standards and instruction. At the foundation of the C3 Framework is an inquiry arc that recognizes the interdisciplinary nature of social studies. It also acknowledges that social studies involves much more than simply learning new content; it includes developing essential literacies and dispositions too.

Principle 1: Position inquiry at the center

First-grade students have just finished listening to their teacher read aloud a biography of George Washington Carver. Hands quickly shoot up into the air. “How did he know you could make so many things out of peanuts?” asks Trinh. “Yeah, can you make lots of things out of other plants, too, like green beans?” questions Jamal. Henry chimes in, “Why did he care about peanuts so much? Was he a chef?”

Young students love to ask questions like these. Fortunately, social studies presents an ideal time to explore such questions, given that “inquiry is at the heart of social studies” (NCSS 2013b) and reflects what historians and social scientists do to gain new knowledge. Students’ questions provide a useful platform on which to set authentic purposes for reading, writing, and talking about informational texts. Regardless of reading ability, students in grades 1–3 can search for answers to their questions through whole group interactive read alouds, shared readings, and using audio and e-books. As students gain expertise with using informational texts to explore their questions, teachers can gradually release responsibility to students through guided small-group inquiry circles (Harvey & Daniels 2009) or through small groups reading and viewing multiple texts focused on a particular topic of inquiry. Teachers of younger students will likely need to remain heavily involved in this small-group time to support students as they make sense of illustrations, photographs, graphics, and text, whereas older students, such as third-graders, can often engage in this small-group work with fewer teacher check-ins.

Recommendations for practice

To help identify potential questions to examine with your class, take a look at your state social studies standards, which may include examples of questions that students might examine. Think about what types of experiences might be useful for students to explore that will address these standards. At the same time, provide opportunities for students to ask their own questions that will drive future reading, discussion, and writing with informational texts. With primary-grade students, we find it helpful to prepare key questions aligned to the standards and then give students space to form their own more specific questions. Third-graders with previous inquiry experience are often ready to jump immediately into brainstorming questions and may not need your assistance; however, having questions drafted ahead of time will help teachers ensure the focus on the standards is not lost. For example:

- Ask “compelling questions” (NCSS 2013, 23) without clear answers like “What does it mean to be a hero, and why are certain people called heroes but not others?”

- Ask “supporting questions” (NCSS 2013, 23) to guide the inquiry like “Who are heroes in our past that we celebrate through holidays?”

As one example, Michigan second-grade civics and government standards require students to learn about the local government of their community. This topic leaves much open to interpretation by teachers. A teacher might decide to work with students to craft the following question: “What types of services should the local government provide?” Then, if some students are interested in transportation, they could choose to research in a small group about how and why the government provides transportation services related to cars, such as local roads and highways. Perhaps other students who love the outdoors could inquire about the services the parks and recreation department currently provides and determine whether any other services might be added based on community need.

Another way to position inquiry at the center of learning is to provide students with some type of shared experience from which they can construct their own questions. For example, one second-grade classroom took a trip to city hall where students were able to meet the mayor, see the room where the city council convenes, and take part in a mock council meeting (Strachan 2016). This trip provided students with an opportunity to raise their own questions about the local government to further explore through reading, writing, and other learning activities. In our experience, teachers are often surprised by the authentic and interesting questions that students generate from such experiences—questions that can provoke future inquiries, such as “Why do we need money to buy things?” or “Who decides how much something costs?”

Principle 2: Gather texts with similar and different perspectives for comparison

Ms. Moss sits at her desk as she discusses her typical instruction with informational texts in her second-grade classroom. She explains, “I try and expose my students to the genres called for in the Common Core—informational texts and literary ones. The problem is that we spend all week exploring one book on a topic in shared reading or read aloud, but the whole focus isn’t on what they’re learning; it’s on the informational text features and strategies. And then the next week we move on to another topic. What connects my lessons isn’t what the children are learning about the world. They’re connected only by the strategies we’re teaching in reading and writing. It feels so inauthentic.”

In our work with teachers in grades 1–3, we regularly hear concerns and even frustrations such as this one: curricular materials are more focused on exposing students to informational text types for the sole purpose of teaching them to read and write rather than recognizing that students can develop many of these literacy practices as they engage in authentic, inquiry-based, and knowledge-building learning. To encourage more meaningful engagement with informational texts, we first recommend building a collection of informational trade books about the natural and social world. With a strong and varied collection in place, teachers can then review the texts for reading and writing strategies, graphics, and text features to teach, reteach, or apply within authentic social studies inquiries.

Recommendations for practice

As you search, we recommend: don’t limit your text search to a specific reading level; rather, seek out texts you think students will find of interest that can be explored through reading aloud and shared reading (such as more complex texts) and independent reading (such as texts with familiar concepts or less complexity).

Even a small collection of different texts from the local library on a similar subject can prove powerful in supporting students’ inquiries. There are a multitude of easily accessible options online, including

- oral texts (e.g., interviews)

- visual texts (e.g., timelines and graphs)

- biographies and profiles

- editorials

-

informational articles

The annual list of Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People also has great recommendations to consider (www.cbcbooks.org/notable-social-studies/).

Gathering a collection of texts on a similar topic will provide opportunities for students to authentically explore their own questions. Text sets that include different perspectives and opinions also encourage young students to begin to develop important disciplinary thinking habits such as comparing sources and identifying biases of authors—key aspects of both the CCSS (NGA & CCSSO 2010) and the C3 Framework (NCSS 2013a). Text sets also expose students to differences in purpose, language, and structure of different informational text types and other aspects of literacy learning (Strachan 2015).

Young students may find text comparison challenging, especially in early primary grades. In first grade, we recommend teachers first model comparing sources with familiar folk or fairy tale texts, such as The Three Little Pigs or The Little Red Hen. Then, we suggest comparing informational text sources discussed in a shared reading format to demonstrate how to make comparisons related to main ideas and significant details in a supportive environment. Teachers can model how to critically engage with text, asking questions such as “Is this an opinion or a fact?” and “How do I know?”

Second-grade classrooms can follow a similar process; however, with scaffolding, many students in this grade are able to begin comparing informational texts via small group inquiry circles or independent inquiry projects. In third grade, the types of questions modeled and posed can increase in complexity, shifting from comparing key details to considering potential author bias and perspectives included or omitted. This aligns with the C3 Framework’s recommendation for students beginning in grade three to “use distinctions among fact and opinion to determine the credibility of multiple sources” (NCSS 2013a, 54).

Principle 3: Provide writing opportunities to authentic audiences

The students in Mrs. Zokowski’s first-grade classroom exude excitement. Their teacher has just explained that, while studying goods and services, they will have the opportunity to work with a partner to produce something they can sell to their fifth-grade buddies. She tells them that they will eventually need to create advertisements for their good or service so that they can convince others to buy it, but today they will focus on identifying and writing about which product they should produce, how the product will work, and who the potential consumers will be (i.e., who might want or need this good or service). Students move into various places throughout the room and set to work brainstorming and writing with their partners.

Both the CCSS (2010) Anchor Standards for Writing and the C3 Framework (NCSS 2013a) encourage us to provide opportunities for young children to consider purpose and audience while sharing newly acquired knowledge with the world. Research shows that students who engage in writing for real-world purposes make significantly greater writing gains than those who do not (Purcell-Gates, Duke, & Martineau 2007).

Steps for Integrating Purposeful Writing and Social Studies

- Map out your school year. Which types of writing (e.g., informative/explanatory; persuasive/opinion; narrative) will you explore during which social studies inquiry? Aim to address each broad writing type during at least two different inquiries.

- Brainstorm authentic genres aligned to each inquiry and the chosen purpose for writing.

- List audiences who might be interested in reading this work, including school audiences as well as those in the community and beyond.

In Mrs. Zokowski’s classroom, students have the opportunity to write plans for their potential product as well as persuasive advertisements to convince their fifth-grade buddies the product is a worthwhile purchase. Unfortunately, this type of purposeful writing is less common in primary grades social studies (Strachan 2016). During social studies, many curricula provide (oftentimes less than engaging) worksheets (Bailey, Shaw, & Hollifield 2006; Hawkman et al. 2015), and many of the children we’ve observed tend to write for an unspecified audience or for their teacher in order to learn about and practice a new genre.

Writing in multiple genres and to authentic audiences during social studies inquiry is an interdisciplinary approach that gives students a clear purpose when writing. This approach can also foster students’ development of social studies dispositions in terms of taking action in the community as an informed citizen. Plus, integrating writing within social studies also helps teachers meet the recommendation by the What Works Clearinghouse that children, beginning in first grade, spend 30 minutes each day practicing and applying their writing skills beyond the 30 minutes spent during writing workshop learning new writing strategies (Graham et al. 2012).

We encourage teachers to help students write for authentic audiences in genres they might encounter beyond school walls, such as a persuasive multi-media presentation, a field guide, a biography, an informational brochure, or a poster detailing an important procedure. Along with writing for authentic purposes, students would be exploring the primary text types emphasized in the K–5 Common Core State Standards (NGA & CCSSO 2010).

During a unit focused on showing good citizenship at school, Mr. Dowd’s classroom of first-graders become very interested in the personal role that citizens play in health care. After interviewing their school nurse and a local pediatrician, students break into small groups and write (with the support of Mr. Dowd) procedural texts to post around the school. Maatla, Lola, and Caleb create handwashing fliers they post in the bathrooms. Lilli, Ella, and Lucas draw graphics demonstrating proper procedures for covering a sneeze, whereas another group writes a family letter with a list of steps to follow when determining whether a child is too sick to attend school. All of these genres exist beyond classroom walls, which means that Mr. Dowd can bring in models to support students’ writing.

Authentic audiences can include school adults, such as other teachers or administrators, as well as community members beyond the school walls, such as family members or government representatives. Even first-graders are capable of considering their audience while writing (Wollman-Bonilla 2001). For example, in one third-grade classroom, students were troubled by the mess left on the playground by other students. They decided to create posters to persuade their schoolmates to clean up their trash at the end of recess. Their teacher reported a high level of motivation to do the writing for all of her writers; she attributed this motivation to having a clearly defined audience who needed to read the information the students were presenting.

Conclusion

Teachers don’t have to choose between including social studies and providing literacy instruction. We argue instead for an interdisciplinary approach that supports purposeful reading, discussion, and writing opportunities with informational texts during social studies inquiry in ways that support learning in both domains. What we describe is not substantially innovative; teachers have been doing this type of work long before the passage of the C3 Framework. Yet it’s time that we shift this type of teaching from individual classrooms to entire schools, districts, and states. By helping young students use compelling and supporting questions as the foundation for inquiry projects, learn from and compare multiple sources, and share newfound knowledge through real genres with authentic audiences, primary-grades teachers have the potential to protect instructional time for social studies; build students’ knowledge base; and support students’ development as readers, writers, and informed citizens.

References

Best, R.M., R.G. Floyd, & D.S. McNamara. 2008. “Differential Competencies Contributing to Children’s Comprehension of Narrative and Expository Texts.” Reading Psychology 29: 137–164.

Bailey, G., E.L. Shaw, & D. Hollifield. 2006. “The Devaluation of Social Studies in the Elementary Grades.” Journal of Social Studies Research 30 (2), 18–29.

Cervetti, G.N., J. Barber, R. Dorph, P.D. Pearson, & P. Goldschmidt. 2012. “The Impact of an Integrated Approach to Science and Literacy in Elementary School Classrooms.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 49 (5): 631–658.

Cervetti, G.N., & E.H. Hiebert. 2015. “The Sixth Pillar of Reading Instruction.” The Reading Teacher 68 (7): 548–551. 2018.

“Knowledge at the Center of English Language Arts Instruction.” The Reading Teacher 72 (4): 499–507.

Demoiny, S.B., & J. Ferraras-Stone. 2018. “Critical Literacy in Elementary Social Studies: Juxtaposing Historical Master and Counter Narratives in Picture Books.” The Social Studies 109: 64–73.

Donaldson, R.S. 2011. “What Classroom Observations Reveal about Primary Grade Reading Comprehension Instruction within High Poverty Schools Participating in the Federal Reading First Initiative.” PhD diss., Utah State University.

Duke, N.K. 2000. “3.6 Minutes Per Day: The Scarcity of Informational Texts in First Grade.” Reading Research Quarterly 35 (2): 202–224.

Duke, N.K., A. Halvorsen, S.L. Strachan, J. Kim, & K. Konstantopoulos. In press. “Putting PjBL to the Test: The Impact of Project-Based Learning on Second Graders’ Social Studies and Literacy Learning and Motivation in Low-SES School Settings.” American Educational Research Journal. DOI: 10.3102/0002831220929638.

Fitchett, P.G., & T.L. Heafner. 2010. “A National Perspective on the Effects of High-Stakes Testing and Standardization on Elementary Social Studies Marginalization.” Theory and Research in Social Education 38 (1): 114–130.

Graham, S., A. Bollinger, C. Booth Olson, C. D’Aoust, C. MacArthur, D. McCutchen, & N. Olinghouse. 2012. Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers: A Practice Guide. NCEE 2012-4058. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Publication#/pubsearch/

Guthrie, J.T., A. McRae, & S.L. Klauda. 2007. “Contributions of Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction to Knowledge about Interventions for Motivations in Reading.” Educational Psychologist 42: 237–250.

Halvorsen, A., N.K. Duke, K.A. Brugar, M.K. Block, S.L. Strachan, M.B. Berka, & J.M. Brown. 2012. “Narrowing the Achievement Gap in Second-Grade Social Studies and Content Area Literacy: The Promise of a Project-Based Approach.” Theory and Research in Social Education 40: 198–229.

Harvey, S., & H. Daniels. 2009. Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles in Action. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hawkman, A.M., A.J. Castro, L.B. Bennett, & L.H. Barrow. 2015. “Where is the Content?: Elementary Social Studies in Preservice Field Experiences.” The Journal of Social Studies Research 39 (4): 197–206.

Heisey, N. 2009. “Reading Aloud Expository Text to First- and Second-Graders: A Comparison of the Effects on Comprehension of During- and After-Reading Questioning.” PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh.

Heisey, N., & L. Kucan. 2010. “Introducing Science Concepts to Primary Students Through Read-Alouds: Interactions and Multiple Texts Make a Difference.” The Reading Teacher 63 (8): 666–676.

Kraemer, L., P. McCabe, & R. Sinatra. 2012. “The Effects of Read-Alouds of Expository Text on First Graders’ Listening Comprehension and Book Choice.” Literacy Research and Instruction 51 (2): 165–178.

Mohr, K.A.J. 2006. “Children’s Choices for Recreational Reading: A Three-Part Investigation of Selection Preferences, Rationale, and Processes.” Journal of Literacy Research 38 (1): 81–104.

NCSS (National Council for the Social Studies). 2013a. The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History. Silver Spring, MD: NCSS. 2013b.

NCSS (National Council for the Social Studies). 2013a. Social Studies for the Next Generation: Purposes, Practices, and Implications of the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards. Silver Spring, MD: NCSS.

NGA (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices), & CCSSO (Council of Chief State School Officers). 2010. Common Core State Standards English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects. Washington DC: NGA, CCSSO.

Pace, J.L. 2012. “Teaching Literacy Through Social Studies Under No Child Left Behind.” The Journal of Social Studies Research 36 (4): 329–358.

Purcell-Gates, V., N.K. Duke, & J.A. Martineau. 2007. “Learning to Read and Write Genre-Specific Text: Roles of Authentic Experience and Explicit Teaching.” Reading Research Quarterly 42 (1): 8–45.

Smolkin, L.B., & C.A. Donovan. 2003. “Supporting Comprehension Acquisition for Emerging and Struggling Readers: The Interactive Information Book Read-Aloud.” Exceptionality 11 (1): 25–38.

Strachan, S.L. 2015. “Kindergarten Students’ Social Studies and Content Literacy Learning from Interactive Read-Alouds.” The Journal of Social Studies Research 39: 207–223.

Strachan, S.L. 2016. "Elementary Literacy and Social Studies Integration: An Observational Study in Low- and High-SES Classrooms." Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Tschida, C.M., & L.B. Buchanan. 2015. “Tackling Controversial Topics: Developing Thematic Text Sets for Elementary Social Studies.” Social Studies Research and Practice 10 (3): 40–56.

Vitale, M.R., & N.R. Romance. 2011. “Adaptation of a Knowledge-Based Instructional Intervention to Accelerate Student Learning in Science and Early Literacy in Grades 1 and 2.” Journal of Curriculum and Instruction 5 (2): 79–93.

Williams, J.P. 2008. “Explicit Instruction Can Help Primary Students Learn to Comprehend Expository Text.” In Comprehension Instruction: Research-Based Practices, 2nd ed., eds. C.C. Block & S.R. Paris, 171–182. New York: Guilford Press.

Wollman-Bonilla, J.E. 2001. “Can First-Grade Writers Demonstrate Audience Awareness?” Reading Research Quarterly 36: 184–201.

Wright, T.S. 2013. “From Potential to Reality: Content-Rick Vocabulary and Informational Text.” The Reading Teacher 67 (5): 359–367.

Wright, T.S., & A.W. Gotwals. 2017. “Supporting Kindergartners’ Science Talk in the Context of an Integrated Science and Disciplinary Literacy Curriculum.” The Elementary School Journal 117 (3): 513–537

Photographs: pp. 38, 43 © Getty Images; p. 44 courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2020 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Stephanie L. Strachan, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Woodring College of Education at Western Washington University, in Bellingham, Washington, where she currently serves as the director of the Language, Literacy, and Cultural Studies program. [email protected].

Meghan K. Block, PhD, is an associate professor of elementary literacy at Central Michigan University, where she teaches literacy courses to both undergraduate and graduate students. Her teaching and research interests focus on early literacy development and instruction. [email protected]