Our Trip Down to the Bay: A Model of Experiential Learning

You are here

Learning through purposeful experiences has long been recognized as an effective approach to teaching children. Pioneers of early education understood the importance of children making sense of their world through observation and experimentation. Their keen understanding of how young children learn continues to influence contemporary approaches to early childhood education.

Today, field trips remain a valuable part of the learning experience, and the educational benefits have been substantiated through years of research. Planned excursions outside the classroom contribute to learning new information (Kisiel 2003; Scribner-MacLean & Kennedy 2007; Nadelson & Jordan 2012) and make content relevant as students integrate that new information with their prior learning (Lei 2010a, 2010b). High-quality field trip experiences lead to increased interest in and a deeper understanding of subject matter (National Research Council 2009).

A variety of factors contribute to a teacher’s ability to implement a successful field trip, including logistical issues, funding, and teacher preparation (Behrendt & Franklin 2014). Due to increased ease of transportation, children are no longer limited to investigating only their own neighborhoods. While visiting places in the immediate community is the best place to start, there are new learning opportunities to be explored. Field trip destinations that were once reserved for older students are becoming more available to children in the early grades. Art museums where the rule was once “look but don’t touch” are embracing child-centered learning through active, sensory-based experiences (Shaffer 2011). Natural history museums that only offered adult-led tours where children were passive learners are now evolving to focus more on children’s interests and to provide active learning experiences (Melber 2008). Museums designed specifically with children in mind are becoming more common, and according to the Association of Children’s Museums, over 40 million children and families visit children’s museums annually (2017).

Field trips also often provide valuable learning opportunities for multiple curricular areas, including those that may receive less time and attention in the classroom, such as music and art (Fries-Gaither & Lightle 2011). When field trips are designed by intentional teachers, children may be engaged in meaningful learning that addresses each subject area (Harte 2013). Math skills may be used as children count, measure, and look for patterns, while observation, prediction, and other scientific process skills may be used to make sense of new information. Vocabulary may build in the context of authentic learning while at the same time, children may be learning more about their community and the various types of jobs people do to support it. Field trips to museums and cultural events may contribute to children’s knowledge of art, strengthen their critical thinking skills, and increase their interest in art and culture (Greene, Kisida, & Bowen 2014).

In addition, carefully crafted field trips offer opportunities to enhance children’s development across cognitive, motor, and social and emotional domains (Bozdogan 2008; Bailie 2010). Children formulate questions and seek answers, use gross and fine motor skills as they explore new environments, and interact with peers and adults during a shared experience. Meaningful social interactions may occur during well-designed field trips because the experience encourages a sense of autonomy and provides time for children to talk about their feelings, ideas, and actions (Tal, Alon, & Morag 2014).

For children and educators to reap these potential benefits of experiential learning, detailed planning is required (Behrendt & Franklin 2014) rather than offering the field trip as a stand-alone experience (Kisiel 2006). In this article, we share a model for planning educationally beneficial field trips and a detailed example from a second-grade class.

A model of developing and implementing field trips

The model for planning and carrying out meaningful field trips is a three-part cycle: the preparation stage, the field trip, and the summary stage (Orion 1993). (For the key features of each stage, see “A Step-by-Step Guide to Field Trips” below.) Each part of the cycle is an independent learning stage, but they are all connected by bridging information from one stage to the next.

An exemplary case: Pelican’s Nest

To share an example of a carefully planned field trip, we developed an exemplary case (Tal, Alon, & Morag 2014) to ensure readers have a clear grasp of the practice and procedures. Our exemplary case is based on a second-grade class that took a trip to the Pelican’s Nest Science Lab. Affiliated with the public school system in Fairhope, Alabama, and located near the Mobile Bay, the Pelican’s Nest Science Lab was established in 1997 and is the signature project of a local nonprofit. The purpose of the Pelican’s Nest is for students in kindergarten through sixth grade to experience firsthand field investigations in the bay and in the lab to create a greater awareness of marine ecology. Programs at the Pelican’s Nest are geared toward marine wildlife and the coastal habitat. Students are actively involved in learning about the marine food chain, animal habitats, aquatic plant life, and weather.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Field Trips

Stage 1: Preparation

- Identify learning objectives and academic standards to be addressed.

- Request curriculum-related materials from the field trip destination.

- Discuss details of the upcoming field trip with the children: where and when they will be going, how they will be transported, what they will see, and the types of activities they will do there.

- Share related materials and resources such as books, photos, videos, and relevant activities.

- Start a K-W-L (Know, Want to Know, Learned) chart (or do a similar exercise to activate children’s prior knowledge and to document their learning).

- Initiate projects related to the field trip site.

Stage 2: The field trip

- Establish expectations and responsibilities of all adults, including the field trip director, chaperones, and classroom teachers.

- Be prepared to assist children who need information clarified and help with maintaining attention in an unfamiliar environment.

- Provide chaperones with a list of rules, a schedule, and the specifics of any activity for which they will be primarily responsible.

- Ensure each child has materials needed to fully engage at the site (such as paper, pencils, clipboards, magnifying glasses, or access to a camera).

Stage 3: The summary

In the days following the field trip:

- Display photos and specimens related to the field trip site.

- Encourage discussion of what children saw, did, and learned.

- Provide additional materials and resources to answer questions children have as a result of the trip.

- Complete the K-W-L chart as a group.

- Complete projects in which children can demonstrate what they learned.

Stage 1: Preparation

The preparation stage is especially important for young children who need time to process new information and adjust to changes in their schedule and surroundings (Taylor, Morris, & Cordeau-Young 1997). At this initial phase, teachers prepare children by introducing and discussing the upcoming trip and related activities based on set goals and educational objectives. Many field trip destinations employ educators who cross-reference their planned programs to state and national standards, including the Common Core State Standards (NGA Center & CCSSO 2010) and the Next Generation Science Standards (National Research Council 2013). They also often have curriculum-related materials and activities that can be used with children prior to or after the visit (Smith-Walters, Hargrove, & Ervin 2014). Teachers can take advantage of these resources as they develop relevant lessons.

When field trips are designed by intentional teachers, children may be engaged in meaningful learning that addresses each subject area.

In the preparation stage, teachers describe the field trip destination and layout with the children (Behrendt & Franklin 2014). Simply orienting children to the novel learning space has been shown to increase learning (Anderson & Lucas 1997). Teachers also explain how the children’s time will be spent there by describing what they will be doing and the type of information they will be learning. To provide important background information and establish a sense of place and purpose, teachers share pictures and books and integrate relevant props into children’s play. Lessons and experiences planned for the preparation stage provide a foundation that helps children build learning connections later (Pace & Tesi 2004; Kisiel 2006; Rennie 2014).

For our exemplary case, second-grade teachers Helen Rivenbark and Jenny Douglass began preparing students two weeks before the field trip. Through an integrated curriculum approach, the students were immersed in relevant activities including reading, researching, discussing, and writing about topics related to estuaries and marine organisms. The unit was introduced through a curriculum web and the creation of a three-column K-W-L chart that depicted what students know and what they want to know prior to the field trip to the bay. After the trip, students added what they had learned to the third column. From experience, the teachers knew that students would benefit most from reviewing everything they had already learned before the actual visit to Pelican’s Nest. Mrs. Rivenbark explained, “It works best when students feel like they are experts before the field trip.”

Field trip discussions will be more engaging when students have studied relevant topics prior to their visit.

At the beginning of the unit, the class brainstormed topics (such as shrimp or barnacles) and decided on alligators to be the primary focus for their research. Next, the students’ research expanded based on their own interests, such as feeding and digestion, habitat, and environmental hazards. Students were encouraged to use text evidence to support their research. To assist with this, the teachers introduced “dash facts” (Portalupi & Fletcher 2001). To create “dash facts,” paper is folded into columns or fourths and the sections are labeled by topic. Students then write quick facts using a dash to begin each one rather than writing them in complete sentences. This keeps the research moving along so the facts can be used as part of a future report.

To find information, students can read books from the school and classroom libraries. They can also access online resources on tablets. Teachers supplement research by introducing new vocabulary and sharing videos, photographs, maps, and other resources. Here are the books Ms. Rivenbark and Ms. Douglass brought to their classroom for the children to explore:

- The Day They Left the Bay, by Mick Blackistone; illus. by Lee Boynton. A cautionary tale of what could happen if people ignore the water pollution plaguing the Chesapeake Bay.

- A House for Hermit Crab, by Eric Carle. A classic children’s story of a hermit crab who outgrew his shell and must find a new one.

- One Tiny Turtle: Read and Wonder, by Nicola Davies; illus. by Jane Chapman. The amazing lifecycle of the Loggerhead sea turtle is told in lyrical text.

- In One Tidepool: Crabs, Snails and Salty Tails, by Anthony Fredericks; illus. by Jennifer DiRubbio. A young girl explores the shoreline to discover the tiny and amazing sea life found in tide pools.

- Sea Turtles, by Gail Gibbons. Facts about the eight species of sea turtles and conservation efforts are supported by clear illustrations and diagrams.

- Seashells, Crabs and Sea Stars: Take-Along Guide, by Christiane Kump Tibbitts; illus. by Linda Garrow. This nonfiction book includes identification information, educational activities, and safety tips.

- Jubilee!, by Karyn Tunks; illus. by Julie Buckner. A young girl witnesses a natural phenomenon with various types of marine life in Mobile Bay.

- Flotsam, by David Wiesner. A curious boy scours the beach for found objects and discovers an underwater camera full of intriguing images.

Stage 2: The field trip

The field trip is the second part of the three-stage model. During this stage, learning occurs in an authentic, informal setting. Children make connections between prior knowledge gained from the preparation stage (as well as from their own personal experiences outside of a school setting) and from the field trip itself (National Research Council 2009). Adults play an essential role during the field trip; therefore, the roles of field trip director, classroom teacher, and chaperone should be clearly delineated.

Second-graders explore the Pelican’s Nest upon arrival.

Ms. Hardman explains how the seine net is used to collect fish.

A parent volunteers to teach a child how to throw a cast net.

Field trip director

If you are going to a site that hosts groups of students often, the field trip director will likely be a staff member of the destination. (If there is no such staff member, then a teacher should serve as the field trip director.) An important role of the field trip director is minimizing the “novelty effect” (Falk 1983); children have a natural tendency to explore new surroundings, so the unfamiliarity of a situation or environment can overshadow the educational concepts being taught. To minimize this, the field trip director should allow time for children to explore and become familiar with the environment before beginning any educational activity.

Kacie Hardman, the director of Pelican’s Nest, said she wanted students to have a “sense of ownership” and an “authentic appreciation for the bay.” She accomplished this through planning age-appropriate activities, such as encouraging free exploration of the lab upon arrival; showing a short video on estuaries; and giving a brief, direct instruction lesson on marine specimens found in the bay and including relevant vocabulary.

Ms. Hardman asked students to discuss two open-ended questions using the turn-and-talk technique: What is an estuary? and Why is it important to us? Having asked these questions of many groups of students, Ms. Hardman knew that the discussion would be more engaging when the students had been studying relevant topics prior to their visit to the Pelican’s Nest.

Next, students went to tables to conduct a water investigation. Ms. Hardman explained how to record observations of water from three different sources in clear plastic cups. The students discussed their observations and then Ms. Hardman tied what they had noticed about the three water samples to an explanation of water sediment.

Before boarding the school bus for the short drive down to the bay, Ms. Hardman shared essential information with the children and chaperones. Three separate activities were planned: students could wade up to their ankles and use dip nets to catch specimens; students could take turns learning how to use a cast net; and students could examine the variety of marine organisms caught by chaperones using a seine net. (Specimens were kept in buckets with water so they could be released later.)

When the class returned to the Pelican’s Nest, Ms. Hardman used the actual specimens collected from the bay for a science lesson. Projecting and enlarging images of the specimens on a monitor, Ms. Hardman facilitated the children’s observations and discussion. Ms. Hardman made connections depending on what students caught and then adapted the lesson to include a discussion of topics such as the juvenile or adult form of a specimen and where that form falls in the food chain.

Classroom teacher

The field trip director is typically responsible for keeping activities interesting for children while allowing the teacher to take on a variety of other responsibilities. Teachers should keep children engaged and help them make connections between the experience and prior knowledge (Pasquier & Narguizian 2006). A balance between connecting with students, supporting exploration, and being available to answer questions or offer assistance should be maintained. Teachers can also assist unfocused or confused students so they will better understand the information available to them (Rennie & McClafferty 1995).

Field trips remain a valuable part of the learning experience, and the educational benefits have been substantiated through years of research.

Due to Ms. Rivenbark’s and Ms. Douglass’s direct involvement in the preparation stage, they were able to help students make connections between their prior research and the information they had learned at the Pelican’s Nest and the bay. At the bay, Ms. Douglass pointed out barnacles on a piece of driftwood, which students examined to determine whether they were living or expired. Behavior management also came into play as teachers assisted with loading and unloading the bus and enforcing safety rules at the bay.

Chaperones

Prior to the field trip, teachers informed chaperones of their roles and responsibilities. Like the students, chaperones need to be oriented to the layout of the site and to the schedule of activities for the duration of the trip. Rules concerning behavior and expectations for children and adults should be clearly explained. If chaperones are directly involved in participating in or leading an activity, they should be prepared in advance of the trip (Kisiel 2006). The teacher should also model behavior and expectations for adult chaperones (Snyder 2011).

The chaperones on the field trip to the Pelican’s Nest were well-prepared for the visit. Ms. Hardman provided a handbook in advance that chaperones were required to read and sign to verify they understood the rules and regulations. These rules were reinforced when the classroom teacher gave final instructions immediately before the field trip. The chaperones played a vital role by loading and unloading gear, demonstrating how to use equipment such as the casting net and seine net, and assisting students in making and recording their observations.

The field trip director, classroom teachers, and chaperones are all important for a successful field trip. Understanding their individual roles and working together as a team allows for maximum learning benefits for students and helps make a memorable experience for all.

Stage 3: The summary

Together, the preparation stage and field trip serve as a concrete bridge toward more abstract learning in the summary stage (Orion 1993). This final stage requires children to synthesize information learned during the preparation stage and the field trip. The combination of experiences results in a deeper understanding and higher retention of knowledge and vocabulary. Teachers may use materials developed by the field trip site staff. Photos, videos, and specimen samples taken and gathered on the field trip can be examined and discussed upon returning to the classroom. Children should be encouraged to act on what they learned through their play and should be given materials to support new activities. Children’s newfound knowledge from the field trip experience may become the basis for their dramatic play, art, and language experiences (New & Cochran 2007).

For the week following the field trip to Pelican’s Nest, Ms. Rivenbark and Ms. Douglass engaged students in related discussions and activities. This provided an opportunity for learning across content areas, such as science (environment, water temperature, organisms); social studies (land mass, geography, environmental issues); math (counting, comparing, weighing); and language arts (reading, writing, visually representing). Students added final details to the K-W-L chart and included any new facts and information relevant to their research. Their final projects took different forms: written reports with detailed illustrations, student-made books, and even a legislative bill and letters of support asking Congress to adopt an official state crustacean.

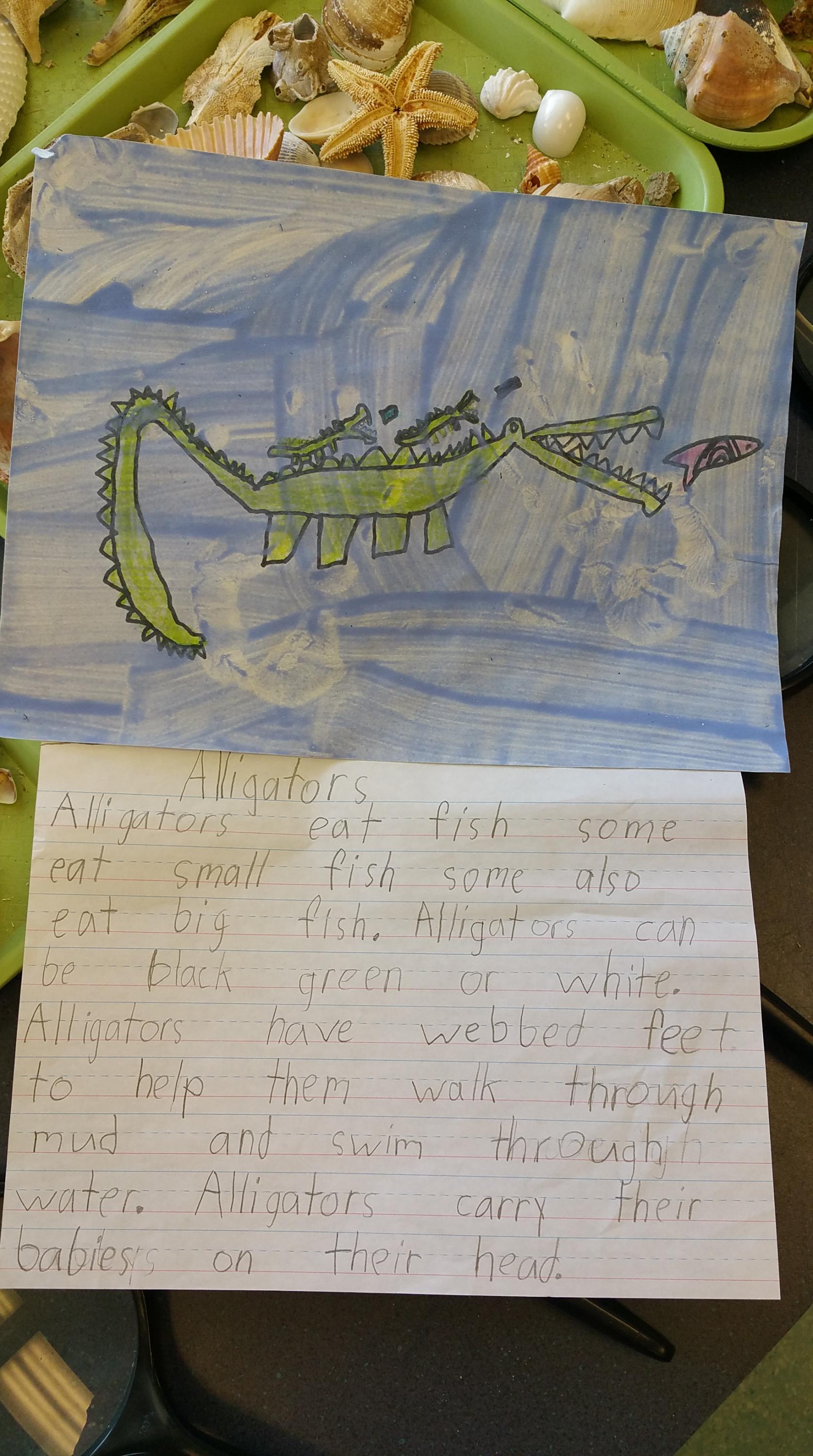

Written reports on the alligator, a native of estuaries.

Conclusion

Although many teachers feel increased pressures of accountability due to standardized testing, the planning and implementation of field trips continues to be an important part of the curriculum. If teachers are limited to a specific number of off-campus field trips per year, then each trip must maximize student engagement and learning through thoughtful planning and alignment to standards. In the exemplary case presented in this article, the field trip acts as an integral piece of a larger science unit. By providing students with an opportunity to explore marine specimens at the Pelican’s Nest and by the bay, students extended their learning beyond the classroom walls and into the natural world. Meaningful experiences such as this one position students to be life-long learners in authentic environments, reinforcing the notion that opportunities for learning are not limited to the classroom but are all around them.

References

Anderson, D., & L.K. Lucas. 1997. “The Effectiveness of Orienting Students to the Physical Features of a Science Museum Prior to Visitation.” Research in Science Education 27 (4): 485–95.

Association of Children’s Museums. 2017. “FY 2017 Annual Report.” Arlington, VA.

Bailie, P.E. 2010. “From the One-Hour Field Trip to a Nature Preschool: Partnering with Environmental Organizations.” Young Children 65 (4): 76–82.

Behrendt, M., & T. Franklin. 2014. “A Review of the Research on School Field Trips and Their Value in Education.” International Journal of Environmental and Science Education 9 (3): 235–45.

Bozdogan, A.E. 2008. “Planning and Evaluation of Field Trips to Informal Learning Environments: Case of the ‘Energy Park.’” Journal of Theory and Practice in Education 4 (2): 282–90.

Falk, J.H. 1983. “Field Trips: A Look at Environmental Effects on Learning.” Journal of Biological Education 17 (2): 137–42.

Fries-Gaither, J., & K. Lightle. 2011. “Penguins and Polar Bears Integrates Science and Literacy.” Science 331 (6016): 413–14.

Greene, J.P., B. Kisida, & D.H. Bowen. 2014. “The Educational Value of Field Trips.” Education Next 14 (1): 79–86.

Harte, H.A. 2013. “Universal Design and Outdoor Learning.” Dimensions of Early Childhood 41 (3): 18–22.

Kisiel, J. 2003. “Teacher, Museums and Worksheets: A Closer Look at the Learning Experience.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 14: 3-21

Kisiel, J. 2006. “More Than Lions and Tigers and Bears: Creating Meaningful Field Trip Lessons.” Science Activities 43 (2): 7–10.

Lei, S.A. 2010a. “Assessment Practices of Advanced Field Ecology Courses.” Education 130 (3): 404–15.

Lei, S.A. 2010b. “Field Trips in College Biology and Ecology Courses: Revisiting Benefits and Drawbacks.” Journal of Instructional Psychology 37 (1): 42–48

Melber, L.M. 2008. “Young Learners at Natural History Museums.” Dimensions of Early Childhood 36 (1): 22–29.

Nadelson, L.S., & J.R. Jordan. 2012. “Student Attitudes Toward and Recall of Outside Day: An Environmental Science Field Trip.” The Journal of Educational Research 105 (3): 220–31.

NGA (National Governors Association) Center, & CCSSO (Council of Chief State School Officers). 2010. Common Core State Standards. Washington DC: NGA Center for Best Practices, & CCSSO.

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. 2009. Learning Science in Informal Environments: People, Places, and Pursuits. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

New, R.S., & M. Cochran, eds. 2007. Early Childhood Education: An International Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Orion, N. 1993. “A Model for the Development and Implementation of Field Trips as an Integral Part of the Science Curriculum.” School Science and Mathematics 93 (6): 325–31.

Pace, S., & R. Tesi. 2004. “Adult’s Perception of Field Trips Taken within Grades K-12: Eight Case Studies in the New York Metropolitan Area.” Education 125 (1): 30–40.

Pasquier, M., & P.J. Narguizian. 2006. “Using Nature as a Resource: Effectively Planning an Outdoor Field Trip.” Science Activities: Classroom Projects and Curriculum Ideas 43 (2): 29–33.

Portalupi, J., & R. Fletcher. 2001. Nonfiction Craft Lessons: Teaching Information Writing K–8. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Rennie, L. J., & T. McClafferty. 1995. “Using Visits to Interactive Science and Technology Centers, Museums, Aquaria, and Zoos to Promote Learning in Science.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 6 (4): 175–85.

Rennie, L.J. 2014. “Learning Science Outside of School.” In Handbook of Research on Science Education, Vol. 2, edited by N.G. Lederman & S.K. Abell, 120–44. New York: Routledge.

Scribner-MacLean, M., & L. Kennedy. 2007. “More Than Just a Day Away from School: Planning a Great Science Field Trip.” Science Scope 30 (8): 57–60.

Shaffer, S. 2011. “Opening the Doors: Engaging Young Children in the Art Museum.” Art Education 64 (6): 40–46.

Smith-Walters, C., K. Hargrove, & B. Ervin. 2014. “Extending the Classroom: Tips for Planning Successful Field Trips.” Science and Children 51 (9): 74–78.

Snyder, S. 2011. “No Accident: Successful Field Trips.” Green Teacher 94.

Tal, T., N.L. Alon, & O. Morag. 2014. “Exemplary Practices in Field Trips to Natural Environments.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (4): 430–61.

Taylor, S.I., V.G. Morris, & C. Cordeau-Young . 1997. “Field Trips in Early Childhood Settings: Expanding the Walls of the Classroom.” Early Childhood Education Journal 25 (2): 141–46.

Photographs: courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2020 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Karyn W. Tunks, PhD, is professor of early childhood and elementary education at the University of South Alabama, in Mobile, Alabama. She is the author of four books for teachers, including Outdoor Play Everyday: Innovative Play Concepts for Early Childhood, and four picture books. [email protected]

Elizabeth Allison, PhD, is the elementary education program chair at Western Governors University, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Elizabeth has conducted research and has published articles pertaining to hands-on inquiry in elementary STEM classrooms.