Diversifying the Workforce: Increasing the Number of Asian Americans in Early Childhood Education

You are here

Despite nationwide attempts to increase the racial and cultural diversity of teacher candidates and in-service teachers, negligible progress has been made in recruiting Asian American educators. At the preschool and kindergarten level, only 2.2 percent of teachers report to be Asian, compared with 12 percent reporting to be Black and 15.3 percent reporting to be Latino/a (USBLS 2021). In addition, teacher education programs lack diversity when compared with other college and university disciplines (Constantine et al. 2009). According to data presented by the US Department of Education, 25 percent of those in teacher preparation programs were from diverse backgrounds, compared with 37 percent in other fields of study. Lower degree completion rates for racially and culturally diverse students, those from families with low incomes, students following a non-traditional path, students with disabilities, and first-generation students further impact the number of diverse teachers entering the teaching profession (ED 2016).

In 2018, 5 percent of students in prekindergarten through grade 12—or roughly 2.7 million children—were Asian American (Irwin et al. 2021). Evidence exists that children benefit when they see their own social identities, including race, culture, and gender, in the individuals who educate and care for them (Dee 2005; Egalite & Kisida 2018; Rasheed et al. 2020). As such, those facilitating educator preparation and professional development programs should consider establishing goals related to race and ethnicity, among other criteria (NAEYC 2020).

Because recruitment and program completion within teacher preparation programs are two aspects that impact the workforce, this article outlines the reasons why individuals enter the teaching profession and shares key recommendations for recruiting and retaining Asian American teacher candidates. Intertwined throughout are the voices of the authors, whose personal and professional experiences demonstrate their dedication to and the need for increasing the number of Asian Americans in the early childhood profession.

Why Work in Early Childhood Education?

In general, individuals are motivated to pursue careers in teaching for altruistic, intrinsic, and/or extrinsic reasons (Fray & Gore 2018):

- Those motivated by altruism are interested in giving back to other people or society, or they are answering a call to teach.

- Those motivated by intrinsic reasons enjoy teaching and working with students, are interested in what they teach, and believe they are good at what they do.

- Those motivated extrinsically may be attracted to teaching for its work-life balance, job stability and availability, and/or because teaching is considered a noteworthy profession.

In examining the literature and comparing it with our own experiences, we found that as Asian American educators, our reasons for entering the profession fall within these parameters.

A Noteworthy Profession

Many individuals who decide to go into teaching do so because they believe it is a noteworthy profession (Fray & Gore 2018). The notion that teachers work to help shape and prepare the next generation seems to be paramount in their minds (Lor 2010; Bryan & Browder 2013). This is the case for Neal Nghia Nguyen and Jun Ai.

Neal Nghia Nguyen

Neal Nghia Nguyen

I grew up in Saigon, Vietnam, during the Vietnam War era. Early education was a luxury for me due to the hardships under the new regime. After several failed attempts to escape the country by fishing boats, my family successfully sought our long overdue freedom in the United States when I was 16 years old.

Before working as a teacher educator in higher education, I taught first grade for five years at several elementary schools in Nevada and Florida. I chose early childhood as my focus because I strongly believe children should be taught, modeled, and given the chance to practice the foundational skills across the five developmental domains as early as possible. A vast body of research has shown improved learning outcomes for children during the early childhood years, when they have the active involvement of families and related stakeholders.

I have always enjoyed working with preservice and in-service teachers in early childhood and special education. These prospective educators need an effective and compassionate role model to guide them through the acquisition of various content-related and prosocial skills during their teacher preparation programs.

Jun Ai

I changed careers from biochemistry and molecular biology to early intervention and early childhood special education. This drastic change stemmed from my lived experience as a daughter of a father with disabilities who struggled with finding quality and equitable services.

My volunteer experiences working with young children with disabilities made it clear to me that the early years are the golden window for educators to make a change in young children’s lives. I know the lasting impact that an early childhood educator can have on young children. It was a lifetime commitment I chose to honor then, and I will honor for the rest of my career.

The Call to Teach

Of the roughly 985,650 center-based early childhood workers who were asked what motivates them to work with young children, more than 60 percent reported “This is my calling or career” (Paschall et al. 2020, 14). This calling has been described as “a way of coming at life, of finding oneself, which is experienced as deeply spiritual and life affirming” (Bullough & Hall-Kenyon 2011, 128). Teaching is something these individuals feel like they were born to do or that they need to do. This exemplifies Shin Silver’s story.

Shin Silver

I knew from the third grade that I wanted to be an elementary school teacher. It was then, as a student in an English language learner class, that I told myself, “This is what I want to do . . . teach.” I wanted to help children who were English language learners like myself. Being an immigrant from South Korea and raised by a single mother who barely spoke English, I knew teaching was going to be my life. I was already teaching my mother the culture and the English language. I became her translator at an early age. Little did I know my life would take me on another path.

As I entered my freshman year of college, my part-time job as a teacher’s assistant at the college’s preschool changed the course of my career. At this preschool, which fostered and advocated for inclusion, I experienced the joy of young children learning and families seeing their children thrive. I saw how large an impact early childhood education has on the trajectory of their lives.

Although I completed my bachelor’s degree in elementary education, my passion for early childhood, and especially inclusion, led me to get my master’s degree in early childhood special education. Now in my 20th year with the same program since my freshman year of college, I have come to realize that this is a part of my legacy—a legacy that shows how much I love working with young children and their families and that gives me a passion to pass on that love to a new generation of teachers. A legacy intertwines educating, coaching, mentoring, and ultimately supporting and building up the multitude of people I come into contact with on a daily basis. I am a teacher.

Inspired by Prior Teachers

A third reason people choose to teach is because another educator influenced them (Liu 2010; Su 1997). Perhaps an inspirational teacher took difficult concepts and—as if by magic—presented them in ways that were understandable and joyful. Here, Jenny Chiappe shares the importance of role models in her journey to becoming a teacher, both in positive ways and ways that made her want to become a role model for her students.

Jenny Chiappe

In high school, my chemistry and math teachers were exemplary, making me want to become a high school science teacher. That trajectory changed in college, when I became interested in developmental disabilities while taking a psychology class. I volunteered at an early intervention clinic for toddlers with autism and eventually decided to pursue a career as a special education teacher. I have been working in schools now for 13 years in different capacities.

Throughout my own educational experiences, I realized the inequities that exist in under-resourced communities. As I reflect back on my experiences as an Asian American and how my parents navigated our educational experiences with translators, I understand the importance of access and advocacy. I realized the importance of representation when I first started working as a teacher. There were not many teachers that looked like me at the school where I worked. I wondered about the importance of diversity within teacher education and the larger community as a whole. As a result of those experiences, my focus is to provide access and equity for students of color at an early age.

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds

Despite the underrepresentation of teachers of color, both in the field and more broadly in media representations of educators (Marrun, Plachowski, & Clark 2019), individuals who pursue careers in teaching may want to work with students who look like them and/or share similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds (Su 1997). They may connect with the educational experiences, biases, and obstacles faced by children of color, and they may want to be a change agent by recognizing and infusing culturally responsive practices into the curriculum.

In addition, many children and families in the United States are dual language and multilingual learners. Thirty-two percent of children birth to age 8 (roughly 11 million children) are dual language learners, and the top five reported home languages (other than English) are Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Arabic (Park, O’Toole, & Katsiaficas 2017). It is important that early educators recognize and support the development of these dual language and multilingual learners (NAEYC 2020). Heather Bae’s contributions stem from her work as a translator and early childhood educator.

Heather Bae

I chose a career in early childhood because I genuinely love interacting with young children. I love that I can make silly voices to make my students laugh. I can pretend to be a tiger, an astronaut, and a monster truck—all within a single day. I have the opportunity to teach children learning-to-learn skills, which will ultimately be the steppingstones of their educational journeys.

I understand the responsibility that comes with being an early childhood educator. It is my responsibility to provide the most secure and stimulating learning environment, guiding each student to acquire new skills and persevere through challenges. I need to connect with their families so we experience the good and the bad together. I also need to collaborate with them to ensure that learning opportunities are presented across all settings (e.g., school and home). Every day is different: some days are easier, and others are more physically and emotionally demanding. Regardless, I go back the next day, anticipating the smiles and silliness of my students, ready to be whatever animal, person, or thing I need to be to make learning intriguing. I simply love that I get to be a part of children’s growth.

There is a significant need for Asian American early educators. Being a Korean American, I communicate with families in their native language, building and maintaining a rapport that may otherwise be difficult due to the language barrier. I act as an instrumental participant in Individualized Education Program meetings by translating for both parents and school staff. Not only that, I can also communicate to Korean-speaking English language learners to increase their understanding. This career gives me the chance to wear many hats.

Becoming a Leader

While the lack of diversity in the teacher workforce is troubling, an even greater disparity exists among individuals in educational administration and leadership. People of diverse backgrounds make up less than 20 percent of principals (80 percent identify as White), and only 6 percent of superintendents identify as individuals of color (Castro, Germain, & Gooden 2018). Furthermore, Asian Americans are more likely to serve in managerial positions in health care, social services, and postsecondary education than in K–12 schools—possibly a carryover from the already low numbers of individuals entering the teaching workforce (Hansen & Quintero 2018).

Here, Delilah Krasch shares her journey from third-grade teacher to working with preschool and kindergarten children to serving as an early childhood administrator in one of the largest school districts in the United States.

Delilah Krasch

I have worked in education for the past 17 years, first as a third-grade teacher, then as an early childhood special education teacher. After seven years, I became a coach and supported other early childhood special education teachers. I felt that, as a coach, I was able to support more students and families by coaching teachers to implement evidence-based instructional practices and by empowering families.

I became an administrator to provide these supports on an even larger scale. My current position gives me the opportunity to continue to advocate for young children and their families across my entire school district. The programs I work with ensure high-quality learning opportunities for students and families living in poverty and for those from historically marginalized groups, including dual language learners, students with disabilities, and racially and culturally diverse students. I supervise coaches who directly provide professional learning, modeling, and mentoring for teachers to ensure high-quality programming for students and families. Together, we provide the foundation for each student’s educational career. I cannot imagine doing anything else.

I was very close to my grandparents growing up, and my grandmother instilled in me the values she learned from her childhood in Japan. I worked hard for my education and am proud to work in an esteemed profession.

A Desire to Be a Male Role Model

Much has been written about the need for male teachers in early childhood education (Cunningham & Watson 2002; McGrath et al. 2020). Despite recommendations offered by experts (Nelson & Shikwambi 2010), men still comprise less than 3 percent of the preschool and kindergarten educator population (USBLS 2021). This trend stems from stereotypical viewpoints that working in early childhood is

- not for men (Bryan & Browder 2013)

- not important (Friedman 2010)

- equivalent to babysitting (Friedman 2010)

Compensation, which is far below what it should be (NAEYC 2021) and less than other professions men may be encouraged to pursue, is also an issue. Further complicating matters, men who do enter the field report being talked down to. For example, Bryan and Browder (2013) report that after a male teacher introduced himself to a parent, the parent’s response was, “That can’t be possible. Are you sure you know what you are doing?” (151). Male teachers may also find it challenging to be the only male teacher on staff (Friedman 2010).

With the already low numbers of early childhood teachers of Asian descent, it is likely that Asian American males represent an even thinner slice. Conrad Oh-Young is one of the few.

Conrad Oh-Young

If you have ever set foot in an early childhood classroom, you have probably seen the toy people set that depicts people dressed in typical work uniforms. The doctor wears a white coat and has a stethoscope, the surgeon wears scrubs and a mask, and the scientist has on a white coat, goggles, and gloves and looks to be mixing different chemicals. Of interest to me were two specific people: the computer person and the teacher. The computer person is depicted as a male with Asian features and is holding what appears to be a computer monitor while the teacher is a White female holding a book and pointing to a picture of an apple.

These two depictions stood out to me because of my nontraditional pathway to the classroom. Having started my career in technology, I always wanted to take that experience and apply it to helping children and their families. In 2008, I made the decision to go back to college. It was difficult while still working full time. Eventually, I earned my teaching license in early childhood special education. I was hired to teach in an early childhood program where children in the district attended a community-based site with children in Head Start. In essence, I was that toy computer person who transitioned to a profession where the stereotypical employee was depicted as someone who did not look like me.

During my service I found that the majority of the children and families I interacted with did not look like me. I thought to myself “This is great!” Although I looked different on the outside, I was still working with everyone else on the teaching staff to show that we all shared the common goal of providing a quality early childhood educational experience for our children.

Though I now work at the university level teaching classes in special education and early childhood, I look fondly upon my time in the classroom. I hope that I made a difference in the lives of the children and families I worked with. I hope to continue making a difference moving forward.

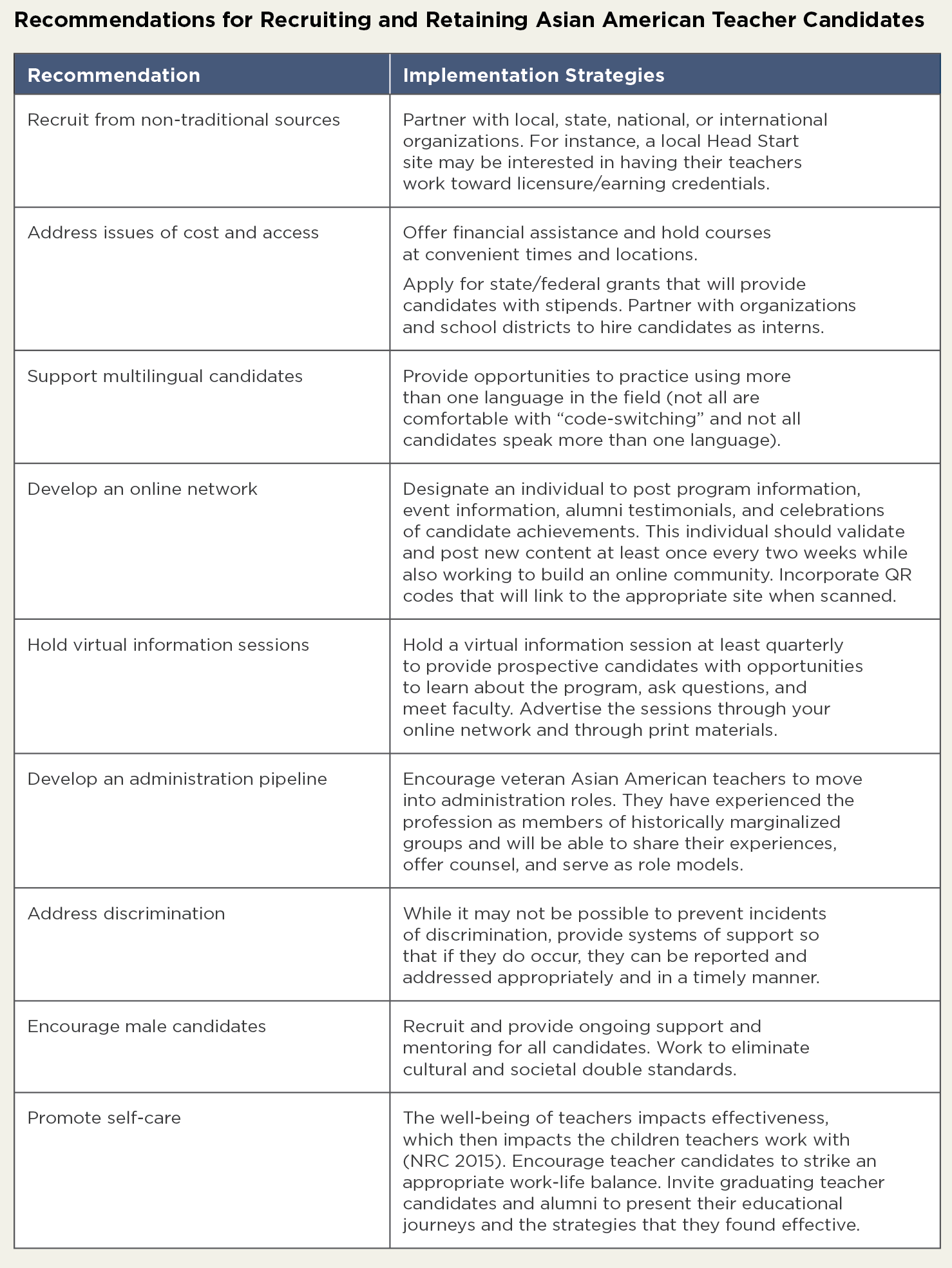

Recommendations for Teacher Education Programs

Asian American teachers continue to comprise a small percentage of the teaching workforce. Teacher preparation programs can help address this lack of diversity by focusing on recruitment and retention in a variety of ways.

- They can expand recruitment efforts to neighboring cities, states, and non-traditional venues such as child care centers, community recreation centers, and places of worship.

- Programs can recruit multilingual candidates who may be able to facilitate relationships with families from diverse backgrounds. (Note that not all Asian American candidates are multilingual.)

- They can develop and maintain an online presence that is separate from the standard university website. Possible avenues include social media (Facebook, Twitter), social networking (LinkedIn), and audio/video sharing sites (YouTube), which can also be used to remain in contact with program graduates.

- Video conferencing software (Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet) can be used to hold virtual sessions where prospective candidates can interact with program advisors to address specific questions.

- Programs can offer financial supports to teacher candidates who may be forced to quit their current jobs because of the time demands made on preservice teachers.

- They can address direct and indirect forms of aggression, discrimination, and prejudice that Asian American teaching candidates may face.

- They can address the implicit and explicit biases that prevent male candidates from pursuing a career in early childhood education.

- Programs can recognize that completing a degree program and starting a teaching career can be stressful. Therefore, they need to ensure that future educators are connected to all available resources that can help them navigate and respond to stressful events and times.

“Recommendations for Recruiting and Retaining Asian American Teacher Candidates,” below, offers several strategies to implement these recommendations. Additionally, identifying administrators who are of similar cultural, linguistic, and/or ethnic backgrounds to interact with prospective and current teacher candidates should not be overlooked. Data suggest that benefits exist to having administrators who look like the students, families, and teachers they serve (Shah 2009; Grissom & Keiser 2011; Grissom, Rodriguez, & Kern 2017).

Final Thoughts

Even with attempts to increase the racial and cultural diversity of teacher candidates and in-service teachers, there is still a lack of Asian American current and future early childhood educators at this time. As programs meet to discuss current student enrollment numbers, syllabi revisions, or changes related to state certification and licensing requirements, they should consider reviewing the population demographics of program completers. We have shared our stories of why we chose to pursue careers in early childhood education along with recommendations that teacher preparation programs can use to recruit Asian American candidates.

This article aligns with the NAEYC Professional Competencies and Standards:

Photographs: © Getty Images; courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

Bryan, N., & J.K. Browder. 2013. “‘Are You Sure You Know What You Are Doing?’ The Lived Experiences of an African American Male Kindergarten Teacher.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Teaching and Learning 3 (3): 142–158.

Bullough, R.V., & K.M. Hall-Kenyon. 2011. “The Call to Teach and Teacher Hopefulness.” Teacher Development 15 (2): 127–140.

Castro, A., E. Germain, & M. Gooden. 2018. Policy Brief 2018-3. Increasing Diversity in K–12 School Leadership. Report. East Lansing, MI: University Council for Educational Administration.

Constantine, J., D. Player, T. Silva, K. Hallgren, M. Grider, & J. Deke. 2009. An Evaluation of Teachers Trained through Different Routes to Certification. Final Report. NCEE 2009- 4043. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Cunningham, B., & L.W. Watson. 2002. “Recruiting Male Teachers.” Young Children 57 (6): 10–15.

Dee, T.S. 2005. “A Teacher Like Me: Does Race, Ethnicity, or Gender Matter?” American Economic Review 95 (2): 158–165.

Egalite, A.J., & B. Kisida. 2018. “The Effects of Teacher Match on Students’ Academic Perceptions and Attitudes.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 40 (1): 59–81.

Fray, L., & J. Gore. 2018. “Why People Choose Teaching: A Scoping Review of Empirical Studies, 2007–2016.” Teaching & Teacher Education 75 (October): 153–163.

Friedman, S. 2010. “Male Voices in Early Childhood Education & What They Have to Say.” Young Children 65 (3): 41–45.

Grissom, J.A., & L.R. Keiser. 2011. “A Supervisor Like Me: Race, Representation, and the Satisfaction and Turnover Decisions of Public Sector Employees.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 30 (3): 557–580.

Grissom, J.A., L.A. Rodriguez, & E.C. Kern. 2017. “Teacher and Principal Diversity and the Representation of Students of Color in Gifted Programs: Evidence from National Data.” The Elementary School Journal 117 (3): 396–422.

Hansen, M., & D. Quintero. 2018. “School Leadership: An Untapped Opportunity to Draw Young People Of Color Into Teaching.” The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/11/26/school...

Irwin, V., J. Zhang, X. Wang, S. Hein, K. Wang, A. Roberts, C. York, A. Barmer, F. Bullock Mann, R. Dilig, & S. Parker. 2021. Report on the Condition of Education 2021 (NCES 2021-144). Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Liu, P. 2010. “Examining Perspectives of Entry-Level Teacher Candidates: A Comparative Study.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 35 (5): 53–78.

Lor, P. 2010. “Hmong Teachers: Life Experiences and Teaching Perspectives.” Multicultural Education 17 (3): 36–40.

Marrun, N.A., T.J. Plachowski, & C. Clark. 2019. “A Critical Race Theory Analysis of the ‘Demographic Diversity’ Gap in Schools: College Students of Color Speak Their Truth.” Race, Ethnicity and Education 22 (6): 836–857.

McGrath, K.F., S. Moosa, P. Van Bergen, & D. Bhana. 2020. “The Plight of the Male Teacher: An Interdisciplinary and Multileveled Theoretical Framework for Researching a Shortage of Male Teachers.” The Journal of Men’s Studies 28 (2): 149–164.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2019a. “Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/equity

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2019b. “Professional Standards and Competencies for Early Childhood Educators.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/professional-standards-competencies

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2021. “Compensation Matters Most: Why and How States Should Use Child Care Relief Funding to Increase Compensation for the Early Childhood Education Workforce.” Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/blog/compensation_matters_most.pdf

NRC (National Research Council). 2015. Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nelson, B.G., & S.J. Shikwambi. 2010. “Men in Your Teacher Preparation Program: Five Strategies to Recruit and Retain Them.” Young Children 65 (2): 36–40.

Park, M., A. O’Toole, & C. Katsiaficas. 2017. “Dual Language Learners: A National Demographic and Policy Profile.” Last modified October 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/DLL-FactSheet-US-FINAL.pdf

Paschall, K.R. Madill, & T. Halle. 2020. “Professional Characteristics of the Early Care and Education Workforce: Descriptions by Race, Ethnicity, Languages Spoken, and Nativity Status. OPRE Report #2020-107.” Last modified December 2020. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/professional-characteristics-ECE-dec-2020.pdf

Rasheed, D.S., J. L. Brown, S.L. Doyle, & P.A. Jennings. 2020. “The Effect of Teacher-Child Race/Ethnicity Matching and Classroom Diversity on Children’s Socioemotional and Academic Skills.” Child Development 91 (3): 597–618.

Shah, P. 2009. “Motivating Participation: The Symbolic Effects of Latino Representation on Parent School Involvement.” Social Science Quarterly 90 (1): 212–230.

Su, Z. 1997. “Teaching as a Profession and as a Career: Minority Candidates’ Perspectives.” Teaching and Teacher Education 13 (3): 325–340.

US Department of Education. 2016. The State of Racial Diversity in the Educator Workforce. Report. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/highered/racial-diversity/state-racial-diversity-workforce.pdf

USBLS (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor). 2021. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Report. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

Conrad Oh-Young, PhD, is an assistant professor of special education and early childhood education at California State University, Dominguez Hills in Carson, California. He has served as an early childhood special education teacher having taught in a preschool age community based program. [email protected]

Jennifer Buchter, PhD, MSW, has worked with young children and their families for over 25 years in multiple areas of early childhood, including childcare, preschool, Head Start, inclusive education, literacy support, day treatment, child welfare, mental health, advocacy, and early intervention. Her research interests include inclusion, social and emotional development, play skills, and supporting young children and families. [email protected]

Delilah Krasch, PhD, is an early childhood coordinator in the Clark County School District in Las Vegas, Nevada. She is also an adjunct instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where she teaches early childhood and early childhood special education graduate and undergraduate courses. [email protected]

Jenny Chiappe, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Special Education at the California State University, Dominguez Hills. Her research interests are the inclusion of students with disabilities and teacher practices to address academic and social needs.

Jun Ai, PhD, BCBA-D, is an assistant professor of early childhood education at the University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, Iowa. Jun has worked as a teacher and early interventionist for young children with and without disabilities across various settings in both the US and China. [email protected]

Shin Silver, MEd, is a head staff at the University of Nevada Las Vegas/Consolidated Students of UNLV Preschool.

Heather Bae, MA, BCBA, is an early childhood special education credentialed behavior interventionist at LAUNCH Preschool in Torrance Unified School District, California. Heather has worked in the field of applied behavior analysis, providing early intervention services to children with autism and other developmental disabilities.

Neal Nghia Nguyen, PhD, is an associate professor of early childhood and special education at Florida Atlantic University in the Department of Exceptional Student Education in Boca Raton, Florida. He has taught at several universities and public elementary schools in Utah, Missouri, Nevada, and Florida. His research interests include early childhood education and development, early literacy skills acquisition, neuroscience and early learning, compassion science, and effective instructional and collaborative practices. [email protected]