But Can I Trust You? Embracing Different Perspectives (Voices)

You are here

Embracing Different Perspectives in an Early Childhood Classroom. Introduction to "But Can I Trust You? Embracing Different Perspectives" | N. Amanda Branscombe, Voices Executive Editor

Trust is a multifaceted, socially risky construct (Krueger & Meyer-Lindenberg 2019) that not only underlies the success of our business and economic structures but is also a pillar on which close relationships and social networks are built.

—Dominic S. Fareri

The foundation for trust and perspective taking is often attributed to adult relationships. However, its basis is in children’s play and interactions. When the children in Teresa Draguicevich’s kindergarten–first grade class invited her to guide their exploration of trust, she knew this was serious business—both for them and for herself. As she wrote when submitting her article to Voices of Practitioners,

I believe this topic (building trust and perspective taking) is extremely relevant to current events in this country and the world for several reasons. First, as educators, we are preparing our students for a world simultaneously struggling to trust diversity of thought while beginning to acknowledge its innovative benefits in the workplace. Yet today’s landscape indicates we are far from establishing the social justice necessary for reaping the benefits of innovation that come from diverse perspectives coming together. Also, as educators, we are working with increasingly diverse populations and are expected to create environments that allow all students to access the deeper learning associated with project-based, collaborative group work. We can empower our youngest learners to bridge their differences and collaborate, leading to lasting and vital change.

Draguicevich’s investigation of trust and perspective taking began with a debate between two children that quickly spilled over to the entire class: Which of their favorite superheroes—Batman or Optimus Prime—was real? How could they trust each other if they did not agree?

Because of her interest in teacher research, Draguicevich decided to use it as her framework for guiding the children. She spent half a year measuring their trust, talking to them about trust and perspectives, designing activities to create a trusting classroom community, then evaluating, measuring, and refining her approaches. She did this research in her role as classroom teacher—walking hand-in-hand and side-by-side with her children—as they each learned how to value different beliefs and perspectives.

Draguicevich provides readers with a summary of her six-month inquiry in this article. She outlines the tools she used for research and observation as well as four approaches she employed to foster the children’s trust and perspective taking. She shares how the children’s initial question about the reality of superheroes spurred her to revisit her classroom practices to ensure that she built trust and respect for differing points of view.

Not only did Draguicevich engage in a sustained inquiry with her students, she also engaged in ongoing analyses of the data she generated so she could make on-the-spot modifications based on her information. This article serves as an example of her persistence in meeting the needs and advancing the knowledge of her students. It also shows how she used teacher research to investigate her choices for activities so that she could follow children’s growth in understanding and demonstrating trust and perspective taking.

Even though her article is published, like most teacher researchers, her questioning and reflections continue. The current inquiry that is an outgrowth of the children’s questions and her subsequent research has now spurred her to turn inward and ask: “How much do I really trust peers whose views differ from mine?”

About the Author

N. Amanda Branscombe, EdD, is an associate professor at Athens State University in Athens, Alabama. She has served as an executive and developmental editor of Voices of Practitioners for many years. As an early childhood teacher educator, she teaches undergraduate courses in play and literacy. [email protected]

References

Fareri, D.S. 2019. “Neurobehavioral Mechanisms Supporting Trust and Reciprocity.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 13 (271): www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00271/full.

“But Ms. Teresa, if Oscar doesn’t believe Optimus Prime is real, how can I trust him?”

In this class of 18 kindergartners and first graders, Alex and his closest friend, Oscar, engage in an ongoing debate during open-choice time about which superhero is real—Optimus Prime or Batman. Soon, keen interest arises among the whole group since everyone has some dearly loved character whose reality they now question. As the debate’s intensity increases, the group requests a class meeting, a Positive Discipline approach regularly used in our classroom to resolve disagreements and to make collective decisions (Nelson, Glen, & Lott 2013).

Because children construct meaning from play, I consider it a privilege when they invite me into their imaginative world as a trusted guide. This moment provides a window of opportunity for me to demonstrate how people can see the same reality from different perspectives. I grab a book off the shelf and join the circle of students already forming on our classroom rug. I ask them to work together to describe the back cover to me, carefully keeping the front cover out of sight. As they take turns sharing details they notice, the group’s mood shifts from concerned to eager. Playfully, I counter every shared detail with an opposing description of the front cover only I can see. They seem to enjoy collaborating to counter my perspective and then express a collective “aha” when I show them the front cover, and they realize the source of our playful disagreement.

With this experience as a framework for our conversation about real versus imaginary superheroes, consensus soon forms around the idea that perhaps it is all right if Optimus Prime is real for Alex while Batman is real for Oscar.

Even though Alex nods with everyone else, he poses a further question: “But how can I really trust my friend if he doesn’t believe the same as me?” The question is directed to the whole group, but he looks intently at me while he asks it. That’s when I realize this question goes beyond differentiating between imagination and reality. Alex wants to know how he can trust and be friends with someone whose fundamental beliefs differ from his own.

Foundations of Trust and Perspective Taking

Every year in my multiage classroom, some culturally contextualized version of the question “Is there a Santa Claus?” bubbles to the surface of what young learners think about and connect to their view of themselves and their relationships. In the situation with Alex and Oscar, Alex was looking for signs that he could trust Oscar, even though their viewpoints differed about the reality of certain superheroes. While I believed Alex would benefit from having friends with different perspectives, I struggled to explain why or how in terms he would understand.

It was one moment, but Alex’s question provided the foundation for earnest inquiry into how children develop trusting relationships and an appreciation for different perspectives. It highlighted for me that children do not automatically learn to trust others or respect different viewpoints just because I model these principles. Realizing this prompted me to consider how I could change my practices so that our classroom community actively built trust and respect for different viewpoints among children without my constant intervention. What tools would help my students bridge these divides to build and sustain trust more independently? I turned to the research to learn what influences children’s capacity to trust and what educators can do to help children build trusting friendships with those whose views differ from their own. A summary of the literature follows.

Establishing Trust

Trust is fundamental to all relationships. It means feeling secure enough in our own beliefs to allow others the right to have a different perspective. For Alex, it meant believing that honoring Oscar’s beliefs would not negate his own. If Oscar did not make fun of him for believing Optimus Prime was real, then Alex could learn to trust their friendship, since learning to trust takes time and depends on individuals’ experiences in their environment and with others (Puig, Erwin, & Evenson 2015).

Children do not automatically learn to trust others or respect different viewpoints just because I model these principles.

Young children learn to discern trustworthiness through relationships: Who can they count on? Who consistently and sensitively cares about them? Who offers them accurate information about their world?

The roots of this trust start in infancy, through relationships or attachment with primary caregivers. The foundation expands during early childhood through relationships with key figures, including early childhood educators, who can guide children toward interpersonal trust. This is “the expectancy held by an individual or group that the word, promise, or written statement of another individual or group can be relied upon” (Rotter 1967, 65) and is the feature that helps children create positive, trusting relationships in a classroom community (Rittblatt & Longstreth 2019). When strong bonds form, children thrive socially and emotionally (Palermo et al. 2007; Raby et al. 2015). In addition, their interactions with other children and their friendships tend to function in healthier, stronger ways (Howes & Tonyan 2000; McElwain & Volling 2004).

Children weigh a variety of information when deciding who to trust. They consider whether a person seems knowledgeable and accurate with their information. They are influenced by a person’s perceived attractiveness, helpfulness or niceness, group membership, and age (Landrum, Eaves, & Shafto 2015; Pesch & Koenig 2018). They wonder about intentions: Does the other person follow through on what they say or promise? (Stengelin, Grueneisen, & Tomasello 2018). Growing to trust others is complicated and cannot be left to chance. Even in the most deliberately diverse classrooms, children often self-segregate, seeking the comfort of sameness (Bronson & Merryman 2009). This can rob them of essential opportunities to develop trusting relationships and to learn from each other within a classroom community.

Perspective Taking

Learning to trust people with different perspectives improves productivity and learning in both the classroom and the workplace (Kelley & Kelley 2013). Like trust, perspective taking—or the ability to understand that someone else’s thoughts, feelings, or internal states might be different from our own—develops over time and is influenced by experience. When children have opportunities to identify and discuss their own and others’ thoughts, feelings, and actions, they gradually come to comprehend that differences exist. They also begin to make progress toward respecting those differences, empathizing with others, and forming and keeping friendships (DeBernardis, Hayes, & Fryling 2014).

Engaging with others who hold different viewpoints or life experiences spurs new learning. Piaget asserted that exposure to differing perspectives and the resulting struggle to make sense of and incorporate conflicting information improve cognition (Pearce 1977). When “children use language to support shared thinking and learning” within diverse groups, they accomplish more together (Fernandez et al. 2015, 54).

However, just bringing children together to talk is not enough. Without providing a supportive framework for recognizing and respecting different perspectives, children (and adults) “have a strong tendency to affirm that what is different from us is inferior” (Freire 2005, 127). Early childhood educators can take an active role in fostering children’s perspective-taking skills by

- intentionally using language that models inclusivity

- designing learning opportunities to provoke children to “benefit from and depend on the expertise of others” (Edwards 1998, 302)

- sharing books that feature diverse perspectives and cultures (Hall 2008)

- broadly building classroom community to create a safer space to express and accept differing perspectives (Puig, Erwin, & Evenson 2015)

With Alex’s question, I found myself challenged to go deeper in my practice to help young learners trust those whose views differ from their own. Spurred by his question of trust and perspective, I embarked on a six-month study to gain a deeper understanding of how I could improve my teaching approaches to increase trust in the classroom. My overarching goal for this research was to build a sense of trust among children that makes room for, helps navigate, and celebrates the variety of perspectives and experiences of each child.

Spurred by Alex’s question of trust and perspective, I embarked on a six-month study to gain a deeper understanding of how I could improve my teaching approaches to increase trust in the classroom.

Methodology

Settings and Participants

I teach at a project-based public charter school with kindergarten through grade 8 in San Diego, California, that serves approximately 350 students. Our children represent a wide range of racial and cultural identities. In addition, 28 percent are children with disabilities, 25 percent come from families with low incomes, and 6 percent are multilingual learners. In my kindergarten–first grade class of 11 boys and seven girls, I aim to create a caring and equitable classroom community where all students trust that they belong and feel their unique perspective is valued.

Procedures

Trust and perspective taking are abstract concepts. To study them and effect change both within my classroom and my teaching approaches, I needed to create a way to measure these concepts in concrete terms. Using Dorothy Cohen’s Observing and Recording the Behavior of Young Children (2008) as a guide, I created a simple checklist to observe children at work as a way to track behaviors related to current and changing social networks or interactions in the classroom and on the playground: With whom do children engage in play? When and where do they approach each other? Who do children reach out to for help from among their peers? Why are they reaching out? Sometimes, I turned these checklists into sociograms for easier pattern analysis. Engaging in conversations with children and observing conversations among them added further clarity to the social behaviors I noticed.

To provide nonverbal methods for students to communicate, I developed my own emoticon surveys to determine my children’s sense of belonging within the classroom community. I used varying degrees of frowning to smiling faces on a scale from 1 to 5, respectively. Sometimes, I gave children a printed copy and asked them to circle an emoticon to answer questions like “Do you believe your classmates are listening to your ideas?” or “Do you feel like the other children are treating you well?” I also asked how many friends they thought they had in class. Other times, I asked the children to point to the emoticons posted in our classroom to help me understand how they were feeling. It took practice for my students to respond—and for me to analyze their responses, which could be influenced by factors such as being tired, hungry, or distracted. I also evaluated survey data in combination with my observation notes and checklists to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how my children were feeling. Overall, the emoticons gave me one more method to collect information. They were especially helpful for multilingual learners and those still emerging in their expressive language.

Finally, I connected with families and colleagues to understand how my efforts to elicit change might be contributing to trust and perspective taking in our larger community of learners. Family attitudes and beliefs are arguably two of the strongest drivers influencing children’s ability to trust and appreciate diversity, so I gathered their input through emails and conversations. I also invited families to join in modeling ways to respect others’ differences and sought their observations and feedback about developing trust and perspective taking in their children over the study’s time period.

As I documented children’s behaviors and words and considered family feedback, I looked for indicators of trust and perspective taking. In particular, I looked for evidence of children

- articulating respectfully what another person believes

- incorporating other perspectives into their work and play

- seeking someone outside of their usual social circle for help or to play

- viewing themselves as a valued member of the classroom community

I coded conversations for phrases indicating emerging trust and perspective taking. These included “I like your idea”; “He really helped me”; “We don’t see it the same, and that’s okay”; “She listened to me.” I compared this information with the survey data as a way to examine children’s reported sense of belonging with their observed words and actions.

As I collected data, I made changes to my teaching based on what I was discovering. To do this, I implemented an improvement research method, which involved engaging in a series of change efforts and then measuring the outcomes to reproduce results in a variety of settings (Bryk et al. 2015). Remaining responsive to the data through iterative cycles of plan-do-study-act helped me determine that four practices encouraged my children to recognize, appreciate, and trust each other on a regular basis:

- Teaching language protocols provided a common language for navigating differences.

- Using concrete objects illustrated complex social concepts and helped children to respectfully acknowledge differences.

- Providing time for collaborative play gave children an opportunity to learn that they can rely on each other even if they do not always agree.

- Creating new affiliations gave them ongoing, positive interactions and memories with each person in class.

With each approach, I noted increasing trust and perspective-taking skills in the classroom. Children began to incorporate other viewpoints into their projects more frequently and to reach out to more of their classmates for help and play. I noted an increased number of exchanges where they respectfully articulated differences from one or two per week to one or two every day. The sociogram and survey results often fluctuated: they tended to spike right after a change effort, only to dip or stop a few days later. However, despite these fluctuations, children’s sense of belonging and willingness to collaborate with different peers in the classroom trended upwards over time. Based on the data, I continued to make incremental changes to my teaching practice.

Changing Practices to Enhance Trust and Perspective Taking

The following examples provide further detail to the four approaches I found most effective for increasing my children’s capacity to trust each other and broaden their perspectives.

Teaching Language Protocols

To give children specific, scripted ways to respond when differences inevitably arose, I created a “Perspectives Wall” and introduced the language protocol, “I appreciate _____  because _____.” To help the children practice, I read They All Saw a Cat, by Brendan Wenzel. In this story, several animals view the same cat through the lens of their unique understanding of the world. After reading the book, my children and I considered ways to use the new language protocol to tactfully describe the cat to the other animals, depending on whether we were the child, fish, dog, mouse, or bird. (“I appreciate the way a bird sees the cat because we get to see the top.”) I also connected this story to our group discussion during the superhero debate about how a book looks different whether viewing it from the front or the back.

because _____.” To help the children practice, I read They All Saw a Cat, by Brendan Wenzel. In this story, several animals view the same cat through the lens of their unique understanding of the world. After reading the book, my children and I considered ways to use the new language protocol to tactfully describe the cat to the other animals, depending on whether we were the child, fish, dog, mouse, or bird. (“I appreciate the way a bird sees the cat because we get to see the top.”) I also connected this story to our group discussion during the superhero debate about how a book looks different whether viewing it from the front or the back.

Next, I unveiled the Perspectives Wall to practice noticing and articulating appreciation when their peers’ answers differed from their own. I posted student answers to open-ended questions such as, “How can we make 10?” At first, we just noticed all the ways we could answer the same question, and I modeled how to express  appreciation for the variety of perspectives. (“I appreciate how Dina’s answer helps us think about another way to make 10 because she takes something away to make something.”)

appreciation for the variety of perspectives. (“I appreciate how Dina’s answer helps us think about another way to make 10 because she takes something away to make something.”)

The Perspectives Wall changed depending upon student inquiry. One time, children collaborated to make a paper tree. As they cut and hung individual leaves, the group decided to find out how many different ways they could make a leaf. I observed three different students using the language protocol to express appreciation for another’s contribution, with statements such as “I appreciate your leaf because it’s so tiny.” The children whose work they acknowledged reported a high sense of belonging on the emoticon surveys that day. One student began coloring his leaf with rainbow stripes after appreciating a classmate’s swirly and colorful design. When I heard him say, “I like Diamond’s leaf because it looks like a rainbow, but I like straight lines better,” I knew my children were beginning to own this process.

Using Concrete Objects to Illustrate Complex Social Concepts

Adding concrete objects to language protocols helped me guide children when they noticed differences. The group had not yet found resolution to Alex’s question, and  their conversations now extended to other fundamental beliefs they discovered they did not share. In response to a subsequent and more heated debate, I gathered the children into an impromptu “Respect Circle.” I put a set of battery-powered candles in the center of the circle, then spun an impromptu story about a group of shining stars who learn to sparkle together in outer space. Each candle represented a child, with the flame representing what makes that child special. As the story ended, each child was invited to board a spaceship, fueling it with words of acknowledgement (“[Insert belief] is important to [insert child’s name], and we respect that”).

their conversations now extended to other fundamental beliefs they discovered they did not share. In response to a subsequent and more heated debate, I gathered the children into an impromptu “Respect Circle.” I put a set of battery-powered candles in the center of the circle, then spun an impromptu story about a group of shining stars who learn to sparkle together in outer space. Each candle represented a child, with the flame representing what makes that child special. As the story ended, each child was invited to board a spaceship, fueling it with words of acknowledgement (“[Insert belief] is important to [insert child’s name], and we respect that”).

Although I improvised this activity, the research about trust and perspective taking informed my choices and helped me address the children’s conflict intentionally. The process helped them calm down enough to become more receptive to these specific concepts:

- Our differences make each of us sparkle.

- When we put our sparkle together, we do not have to change the way we each shine.

- Our combined light brightens the room with joyful learning.

This activity seemed to help children focus on what they stood for in the heated debate rather than who they stood against. It also provided me a way to guide them from within the story rather than lecturing them. At the end of the day, children’s reported sense of belonging on the surveys increased 62 percent from the previous week. Throughout the rest of the month, I observed they more readily incorporated other viewpoints into their work, such as during this overheard exchange:

Olivia: I trusted you people! (In response to a group knocking over a block structure.)

Teacher (to Olivia): How can we help you trust again?

Olivia: Listen when I talk. Just don’t knock it down, OK?

John: OK, I appreciated your house because it had many rooms, but can we make a bigger one this time?

Sondre: Can we add booby traps?

Olivia: But if we do that, we need to keep the living room and the front door. OK?

Sondre: OK, I can respect that!

Providing Time for Collaborative Play

With guidance, children’s collaborative play incorporated these social and emotional skills more independently. As Cohen explains, “Children project themselves into their play and work out problems of both intellectual comprehension and emotional complexity” (2008, 70). In my class, a small group of children began creating their own stage play, including a plot, props, and costumes. Soon, most of the class joined the effort. During this process Alex shared, “I appreciate Oscar because he shows me cool moves for the play.” This was noteworthy—since their superhero debate, the number of times Alex and Oscar chose to play together at school had decreased from multiple times every day to only a few times per week.

When I realized that the effort required to create this play was helping the two trust and even appreciate their differences, I paused other classroom plans and guided the children to ensure everyone participated. This was important for Diego. Because he tended to be less imaginative and more literal in his play, his classmates often did not include him in pretend scenarios. He had not joined the stage play activity; through conversations with him, I discovered that he did not know how to enter the play. I began to help Diego explore some ways to access group learning. Eventually, he chose to make a loud clapping sound while saying, “Quiet. Camera. Action” before the start of each scene. At first, many children seemed startled by his sudden contribution, but then several expressed appreciation: “We appreciate Diego’s banging because it helps us know when to start,” and “Wait, we can’t start until Diego tells us!” That day, Diego reported he had many friends in the classroom—an increase from his usual response of two friends (one of which was me).

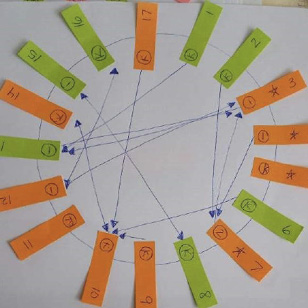

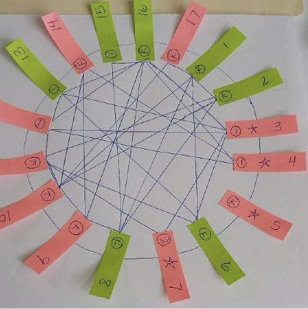

Social interactions among children before they began their stage play. |

Social interactions among children during their stage play activities. |

The sociograms above illustrate the alliances that formed as children self-segregated in response to Alex and Oscar’s superhero debate, compared with the marked increase in reaching out to new peers during the student-initiated theatrical production.

Creating New Partnerships

Although guiding children’s collaborative play positively influenced social interactions, sustained connections occurred the most when I systematically partnered children. We called these partnerships “buddies.” I posted buddy pairs each morning in a prominently displayed pocket chart. These pairings changed daily, so eventually each child partnered with every other child. During our morning meeting, we engaged in playful activities with partners. Throughout the day, I encouraged children to continue connecting with their buddies. It even became a way for me to quickly organize small groups. “Find your buddy! Now buddies, find another set of buddies!” According to surveys, no one felt left out (as can often happen when forming groups). Buddies seemed to provide a consistent framework for social connection.

Additionally, I found it useful to partner children when minor disputes arose. When I learned one student thought another was his “arch nemesis,” I partnered them. By the end of the day, his mother reported him saying, “She’s not so bad when you are with her one-on-one.” I decided to partner them again and at the end of the next day, he declared he wanted to marry her.

When issues or tough moments arise, teachers can begin to address them by opening their eyes and ears to children’s conversations, behaviors, and interactions.

After implementing this partnering system, I encouraged buddies to check in with each other using the emoticon surveys and ask the questions of each other. Students’ positive responses increased by 50 percent, a level that was maintained for the remaining two months of the study. Knowing a classmate cared seemed to have a positive impact.

In the beginning, some children complained when they were not partnered with a preferred classmate, so I photographed and posted buddy activities to increase the number of positive interactions (and memories) they had with each other. Over time, even the more reserved students came in each morning eager to see the buddy chart and wall, and earlier hesitations or complaints went away. Buddies quickly became a regular part of our classroom culture. As one student exclaimed, “At the beginning of the year, I had a few friends, but now I know everyone in the class is my friend!”

Conclusion

Any difference can potentially become a wall between people. It is not easy to trust someone whose views differ from one’s own, nor is it simple to support someone struggling to trust others. Educators play an important role in helping children learn to trust those they perceive as different by removing walls of distrust and serving as a bridge—the connector between children—until those students are secure in their bonds with each other.

In reflecting on this study, I learned that when issues or tough moments arise, teachers can begin to address them by opening their eyes and ears to children’s conversations, behaviors, and interactions. For this group of children, issues of trust and perspective taking sparked disagreement, taking sides, avoiding collaboration, and struggling to trust others with different viewpoints. Taking the approach of a teacher researcher, I turned to the literature and gathered my own data. I developed and introduced language protocols, used concrete objects to represent complex concepts, guided children’s collaborative play, and purposefully paired children who did not often socialize. Each effort to effect change encouraged greater trust and perspective-taking skills—something I hope extends to other areas of my students’ lives.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- Peruse an archive of Voices articles

- Read the Fall 2021 Voices compilation

References

Bronson, P., & A. Merryman. 2009. “Even Babies Discriminate: A Nurtureshock Excerpt.” Newsweek. Retrieved from www.newsweek.com/even-babies-discriminate-nurtureshock-excerpt-79233.

Bryk, A., L. Gomez, A. Grunow, & P. LeMahieu. 2015. Learning to Improve: How America's Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Cohen, D.H., V. Stern, & N. Balaban. 2008. Observing and Recording the Behavior of Young Children. New York: Teachers College Press.

DeBernardis, G.M., L.J. Hayes, & M.J. Fryling. 2014. “Perspective Taking as a Continuum.” Psychological Record 64 (1): 123–31.

Edwards, C. 1998. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach. Greenwich, CT: Alex Publishing.

Fernandez, M., R. Wegerif, N. Mercer, & S. Rojas-Drummond. 2015. “Re-Conceptualizing Scaffolding and the Zone of Proximal Development in the Context of Symmetrical Collaborative Learning.” Journal of Classroom Interactions 50 (1): 54–72.

Freire, P. 2005. “Letter Eight: Cultural Identity and Education.” In Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those who Dare to Teach, expanded edition, 123–133. New York: Westview Press.

Hall, K. 2008. “Reflecting on Our Read-Aloud Practices: the Importance of Including Culturally Authentic Literature.” Young Children 63 (1): 80–86.

Howes, C., & H. Tonyan. 2000. “Links Between Adult and Peer Relations Across Four Developmental Periods.” In Family and Peers: Linking Two Social Worlds, eds. K.A. Kerns, J.M. Contreras, & A.M. Neal-Barnett, 85–113. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Kelley, T., & D. Kelley. 2013. Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All. New York: Crown Business Random House LLC.

Landrum, A.R., B.S. Eaves, & P. Shafto. 2015. “Learning to Trust and Trusting to Learn: A Theoretical Framework.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 19 (3): 109–111.

McElwain, N.L., & B.L. Volling. 2004. “Attachment Security and Parental Sensitivity during Infancy: Associations with Friendship Quality and False-Belief Understanding at Age 4.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 21 (5): 639–67.

Nelson, J., J.A. Glen, & L. Lott. 2013. Positive Discipline in the Classroom: Developing Mutual Respect, Cooperation and Responsibility in Your Classroom. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Palermo, F., L.D. Hanish, C.L. Martin, R.A. Fabes, & M. Reiser. 2007. “Preschoolers’ Academic Readiness: What Role Does the Teacher–Child Relationship Play?” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 22 (4): 407–22.

Pearce, J. 1977. Magical Child, Plume edition. New York: Penguin Books.

Pesch, A., & M.A. Koenig. 2018. “Varieties of Trust in Preschoolers’ Learning and Practical Decisions.” PLoS ONE 13 (8). https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0202506.

Puig, V., E. Erwin, & T. Evenson. 2015. “It’s a Two-Way Street: Examining How Trust, Diversity, and Contradiction Influence a Sense of Community.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 29 (2): 187–201.

Raby, K.L., G.I. Roisman, R.C. Fraley, & J.A. Simpson. 2015. “The Enduring Predictive Significance of Early Maternal Sensitivity: Social and Academic Competence Through Age 32 Years.” Child Development 86 (3): 695–708.

Rittblatt, S.N., & S. Longstreth. 2019. “Understanding Young Children’s Play: Seeing Behavior Through the Lens of Attachment Theory.” Young Children 74 (2): 78–84.

Rotter, J.B. 1967. “A New Scale for the Measurement of Interpersonal Trust.” Journal of Personality 35 (4): 651–665.

Stengelin, R., S. Grueneisen, & M. Tomasello. 2018. “Why Should I Trust You? Investigating Young Children’s Spontaneous Mistrust in Potential Deceivers.” Cognitive Development 48: 146–154.

Teresa Draguicevich, MEd, teaches at Innovations Academy in San Diego, California, and is cofounder of Learning Journeys Forum. She has worked for 30 years in early childhood settings to create equitable educational environments for children of all backgrounds. [email protected]