Our Proud Heritage. Intentional Use of Technology to Foster Learning and Relationships: The Legacy of Fred Rogers

You are here

Although children’s “outsides” may have changed a lot, their inner needs have remained very much the same. Society seems to be pushing children to grow faster, but their developmental tasks have remained constant. No matter what lies ahead, children always need to know that they are loved and capable of loving. Anything that adults can do to help in this discovery will be our greatest gift to the future.

—Fred Rogers, Many Ways to Say I Love You: Wisdom for Parents and Children from Mister Rogers

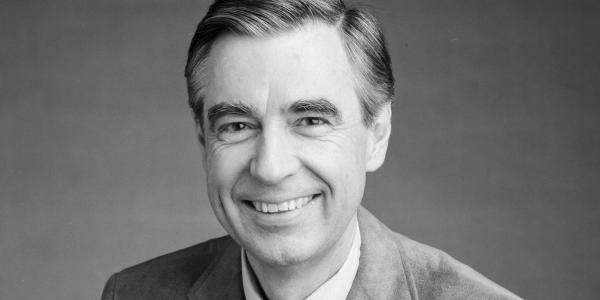

More than two decades after his death, Fred Rogers (known as Mister Rogers to most of us) continues to make his mark—on our society, on our profession, and on the world’s children. Words and images from Rogers’ work continue to emerge and re-emerge, reminding us that none of us stands alone, that the ability to navigate emotions and relationships is seminal to our own well-being as well as that of others, and that technology is not meant to be a simple answer to complex problems but rather a tool to be intentionally used for positive interactions and outcomes.

While Rogers was certainly a television pioneer, he was also a tenacious and grounded scholar in the field of child development. He understood the crucial significance of social and emotional learning and the powerful potential of early childhood education in supporting it. He embraced technology as a helpful tool that allowed him to reach children and support these areas of development. Without a doubt, the legacy of Fred Rogers is an exemplary part of the heritage of the early childhood field, especially in the areas of child development, social and emotional domains, and the thoughtful creation and integration of technology and media.

Fred Rogers’ Legacy and the NAEYC and Fred Rogers Center Joint Position Statement on Technology and Interactive Media

The legacy of Fred Rogers informed the development of the NAEYC and Fred Rogers Center joint position statement “Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8.” Rogers’ work and expertise were grounded in child development research. Keeping children and their needs at the center of his practice, he showed how technology can be used to support children’s learning. He harnessed the newly developed technology of television to reach children and families. Through his careful, intentional use of the media, he built relationships with viewers and bolstered children’s social and emotional development.

Key messages in the position statement flow from Rogers’ belief that, when used intentionally, technology can benefit children and families. Reflecting Rogers’ emphasis on child development research, the position statement notes, “Early childhood educators always should use their knowledge of child development and effective practices to carefully and intentionally select and use technology and media if and when it serves healthy development, learning, creativity, interactions with others, and relationships” (NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center 2012, 5). Similar to how Rogers elevated children’s development and learning in the context of his work in television, the position statement notes that technology should be used intentionally within the framework of developmentally appropriate practice—considering each child’s individuality as well as the context of the child’s family and community.

The Early Life and Work of Fred Rogers

Fred McFeely Rogers (1928–2003) began his life in the small town of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, just prior to the Great Depression. His childhood was hallmarked by privilege and challenges, elements that had lifelong impacts. On one hand, he was born into a family of financial means, lived in a lovely home in a well-resourced neighborhood, and had caring parents who consistently modeled ways to notice and tangibly help those in need. On the other hand, his childhood was also marked by teasing, bullying, insecurity, and illness—painful elements that made young Rogers deeply self-reflective as well as very sensitive to the feelings of others.

During difficult times, he learned to draw strength from the strong sense of place offered by his community and from the words and tangible support of trusted others (King 2018). As Rogers later explained during a special television interview, when he was a boy and saw scary things in the news, his mother said to him, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping” (Rogers 2001, 71). When alone, he enjoyed music, reading, and creative outlets such as puppetry. He not only found comfort in these pursuits but also honed talents that he would draw on throughout his life.

As he matured, Rogers continued to develop his academic and musical talents, gained an increasing sense of confidence, and built friendships, eventually becoming student council president of his high school. Upon graduation, he pursued studies first at Dartmouth and later transferred to Rollins College in Florida, where he received a degree in music composition. He had a sense of calling and planned to pursue the ministry. Through all the ebb and flow of maturing, Rogers’ life was marked by challenges as well as by a keen awareness of his feelings, a strong work ethic, and a deep desire to help others. These elements, so necessary for growth, contributed to a strong sense of resilience.

Biographer Max King (2018) noted the following about Rogers’ development and ability to face challenges:

From his earliest years, he took his fears, his loneliness and isolation, and his insecurities and turned them to his advantage. Somehow, he was almost always able to take his feelings into a place of deep introspection and emerge with a fresh and often brilliant, new direction. (50)

This characteristic tenacity and growth—as well as uncovering a new direction—through applied life lessons can be found in Rogers’ early and ongoing encounters with children’s television. The early days of children’s programming often consisted of clownish, “pie-in-the-face” slapstick comedy and humor that came at the expense of others, which Rogers found to be shocking and demeaning. Yet he also quickly grasped the potential of this new technology. He believed that he could transform it in a manner that would deeply benefit children. More than a passing thought, this possibility changed the course of Rogers’ life and eventually also changed the future of children’s television. This decision temporarily moved Rogers away from his planned ministerial studies and drew him toward work in the media. He began to envision ways in which he could use his considerable musical, creative, and communication skills together in the new world of television broadcasting. He seemed to instinctively know that a focus on children’s social and emotional development had to be at the very heart of this work (NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center 2012).

Welcome to the Neighborhood: A New Approach to Children’s Television

After graduation from college, Rogers eventually landed close to home, working in Pittsburgh to help found WQED, the nation’s first community-supported television station. From 1954 to 1962, he worked behind the scenes on Children’s Corner, an early children’s program with puppets and music. It was from this base that he would eventually launch Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood to a national audience in 1968.

From the beginning, he knew he did not want this to be a typical television show. Rather, he envisioned the daily program as a “television visit” between himself and his young audience. Each visit began with a welcoming song as Mister Rogers entered his “television house” and concluded with a closing song as he exited to return to his real home. In between, the visit included developmentally appropriate, straightforward talks about important matters such as emotions, family, friends, everyday situations, meaningful play, daily routines, and the growing pains and good feelings that come with maturing. During these talks, he looked directly into the camera, creating the sense that he was speaking personally to each one of his young television visitors. These messages consistently affirmed young viewers, reminding them that they were special, that he liked them just the way they were, that feelings were part of being human, and that it can help to talk about feelings. Through his words and songs, Mister Rogers helped children process anger, jealousy, fears, separation, sadness, and joy. For example, his song “What Do You Do with the Mad that You Feel?” conveyed to children that anger is natural and normal and that there are healthy ways of dealing with anger—so that we do not hurt anyone or damage anything.

The program also featured many other elements, offering viewers a well-rounded television visit through a tapestry of experiences (Sharapan 2012) built on active and playful engagement and relationships. Knowing that rituals and routines are essential for establishing trust, a sense of security, and an openness to learning, Rogers incorporated predictability into each of the 900 episodes in the series. Each episode included established routines, such as greetings, feeding the pet fish, and Mister Rogers changing attire (into a cardigan and sneakers to indicate the start of the visit and returning to more formal shoes and attire to indicate a return to business and the end of the visit). Some programs included additional engaging content, such as a trip to the crayon factory or visits with different friendly residents of the neighborhood, such as Mr. “Speedy Delivery” McFeely (played by David Newell), Handyman Negri (played by jazz guitarist Joe Negri), or Officer Clemmons (played by singer/actor François Clemmons).

Viewers were also introduced to others from well beyond the neighborhood, such as renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma, famous chef Julia Child, and Eric Carle, the author and illustrator of many popular children’s books. These visits not only opened the world to Rogers’ young viewers, they also offered models of key social and communicative skills, such as ways to greet others, make introductions, engage in conversation, ask questions, and show appreciation for the work and interests that others shared.

Visits to Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood also featured a “visit within a visit.” In every episode, Mister Rogers invited viewers to join him on a whimsical ride on Trolley, an electric model trolley that served as a type of character in itself. More than transportation, Trolley was a tangible connector between reality and imagination as it transported viewers to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. Upon arrival, viewers encountered a full cadre of puppet characters who were living out their lives together as “neighbors.” The puppets ranged from the shy, sensitive Daniel Tiger to the mischievous Lady Elaine Fairchilde, the curious X the Owl, the demure Henrietta Pussycat, and the arrogant but caring King Friday XIII and his royal family. Together, the puppet characters raised concerns, expressed feelings, and learned how to manage conflicts and cope with difficult situations. They grew in their connections with one another through the help and support of their human friends, who were regulars in their neighborhood. Both the puppets and the unique character development each displayed came directly from Rogers. Tapping into the puppetry skills he had honed since childhood, he created the personalities that brought each puppet character to life and used them to give voice to the thoughts and concerns common to childhood.

After visiting the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, Trolley brought viewers back to the familiar television house—a transition back to the real world—where Mister Rogers reflected on the situation, how the characters dealt with their feelings, and how they resolved the Make-Believe story (Whitmer 2004; King 2018). The program always ended with the familiar closing song and routines, along with Mister Rogers’ assurance and commitment, “I’ll be back next time.”

Strong Foundations in Child Development Research

Fred Rogers, along with the cast and production team of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, harnessed technology to offer the gift of support for social and emotional learning to viewers across the country (Sharapan 2015). Part of the art of the program was its potential to do this through the presentation of complex concepts, such as relationships, emotions, and self-concept, in an accessible way that young children could comprehend. The content was presented in a manner that seemed as comfortable as Rogers slipping into his favorite cardigan. However, the approach to program development was far from casual. Rather, it flowed from steady foundations. Each program was carefully scripted—intentionally planned—by Rogers based on an understanding of child development and how to meet the needs of children in meaningful ways.

Indeed, the underlying foundation of Rogers’ creative work in children’s television grew out of his graduate studies in child development at the University of Pittsburgh. This program led to a decades-long collaboration and mentoring relationship with Dr. Margaret McFarland, renowned psychologist on the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine faculty. McFarland provided insight into the child development research and family dynamics underlying the themes that Rogers addressed in his scripts. Hedda Sharapan (associate producer of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood) recalls that when she approached Rogers about the possibility of working in children’s television, she was surprised when he suggested that she pursue studies in child development rather than television production. For Rogers, children and what was important to their development always came first.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood focused on the power of relationships and highlighted compassion, empathy, and the development of self-regulation, long before social and emotional learning was popularized (Sharapan 2015; King 2018; Rogers 2001). In his work, Rogers outlined a series of principles related to crucial areas in children’s development (Paciga et al 2017, 3). These include

- a sense of self-worth

- a sense of trust

- curiosity

- a capacity to look and listen carefully

- a capacity to play

- times of solitude (open-ended moments that nurture a sense of comfort in being with themselves)

These principles are well-supported by a swathe of research and professional recommendations indicating that social and emotional learning is vital to children’s healthy development and overall well-being, fosters a sense of trust and safety, and contributes to a more equitable educational environment (CASEL, n.d.; Denham 2018; Ho & Funk 2018; Kaspar & Massey 2023). As children develop these important habits of heart and mind, they are better positioned to understand and interact with peers and others in society in ways that are fair and just. (For further resources on this topic, see “Resources for Accessing and Extending the Social and Emotional Work of Fred Rogers” below.)

Resources for Accessing and Extending the Social and Emotional Work of Fred Rogers

Check out the following resources for more information on the legacy of Fred Rogers and his work on children’s social and emotional development.

-

Fred Rogers Institute

The institute was established to advance Fred Rogers’ life and legacy. Located on the campus of Saint Vincent College in Rogers’ hometown of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, the physical center includes exhibits and houses an extensive archive with more than 22,000 artifacts. The institute offers ongoing opportunities for both virtual and in-person learning and professional development and is a hub for related research. fredrogersinstitute.org -

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood

Created by Fred Rogers Productions (fredrogers.org), this site offers a virtual look into the people, places, music, and messages of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Visitors can learn about Mister Rogers, view video clips, sample full programs, and sing along with music from the series. misterrogers.org -

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

CASEL includes a well-developed framework for social and emotional learning and is a hub for related research. The site highlights practical ideas for implementing research-based social and emotional learning. casel.org -

What We Can Continue to Learn from Fred Rogers

This accessible newsletter is written to explore the applications of Fred Rogers’ legacy for the learning and development of today’s children. It is written by Hedda Sharapan, who has served for 56 years in the production and development of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and the Fred Rogers’ legacy. fredrogersinstitute.org/resources/slowing-down

Implications for Early Childhood Educators

The world is much different for children now than it was in the early days of television and the creation of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. (As noted in the opening quotation, Rogers used to say, even though the outsides of children may have changed, their insides haven’t.) However, Rogers continues to have an impact today, and his work offers many lessons from which we, as early childhood professionals, can draw. Among these are the following:

- A sense of purpose is important, which provides guidance in making decisions about practice. Educators can benefit from having a sense of calling. Seeing an overall purpose in our work can serve as an anchor and help us to set priorities for our practice. For example, while Rogers had many different talents and professional opportunities, he was never swayed from his central goal of using television as a means to promote the learning and development of children. Likewise, early childhood professionals can consider their own priorities and sense of mission as they develop professionally in specific areas, such as working with particular age groups, deepening their knowledge of a particular aspect of the curriculum, or honing their talents to be effective administrators and leaders.

- Effective practice is collaborative and research based. Rogers worked with mentors and also became a mentor to many others. We can refine our practice by working collaboratively with mentors and continually learning from research. In addition, early childhood educators can contribute to the development of others in the field by engaging in action research related to elements of pedagogy, social and emotional climate, and learning in their own classrooms.

- Children develop in social and emotional domains in different ways and across the curriculum. While some social and emotional development happens through direct discussions of emotions and feelings, it also unfolds through other avenues, such as through the use of music, puppetry, drama, and other creative and expressive modes. Many social and emotional concepts can be effectively taught through real-life interactions as well as integrated throughout the curriculum. For example, self-reflection, turn taking, and respectful communication can all be infused into the daily routines in any setting. Children can work together as they use their observational skills to notice the wonders in the world of science, collaborate on ideas for block building to nurture engineering perspectives, and acknowledge different ways to approach problem solving in math-related activities.

- Technology and media can be beneficial tools for learning, when used intentionally. Although many were wary of the potential negative impact of children’s television, Rogers chose to embrace its potential and to transform the medium for the benefit of children and families. An optimistic approach and openness to new technologies and experiences can lead to active, meaningful learning. For example, many children seem drawn to interacting with robots and engaging with different forms of unplugged coding. These learning experiences offer children opportunities for computational thinking and can contribute to building valuable skills that can be applied in later STEM learning, with and without a screen.

Concluding Thoughts

Decades after his death and well over half a century after his television launch, the public interest in and devotion to Fred Rogers remain strong and are a striking testament to his legacy. (See “Books and Movies About Fred Rogers” below for a list of works celebrating his life and contributions.) An icon of twentieth century culture and perhaps the best-known persona of children’s television, Rogers offered more than a continual stream of quality programming. He offered viewers the gift of a steady, stable, and caring presence. For generations of young children, he was an adult (and sometimes the adult) on whom they could count. Although situated on the other side of a screen, Mister Rogers “showed up,” understood, and put words to the often unspoken feelings and concerns of children. He was a steady presence who called young viewers “television friends” and regularly welcomed them into his “television house” and neighborhood. He recognized television to be the cutting-edge technology of his day and lassoed it, bringing it into service to support the development and social and emotional learning of children.

The author gratefully acknowledges the significant contributions of Hedda Sharapan and Margy Whitmer, who generously shared their time, expertise, and firsthand stories of working closely with Fred Rogers in the production of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and the development of Fred Rogers’ legacy.

Photographs: Photos by Walt Seng. Courtesy of Fred Rogers Productions.

Copyright © 2023 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning). n.d. “How Does SEL Support Educational Equity and Excellence?” Advancing Social and Emotional Learning. Chicago, IL: CASEL. casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/how-does-sel-support-educational-equity-and-excellence.

Denham. 2018. “Keeping SEL Developmental: The Importance of a Developmental Lens for Fostering and Assessing SEL Competencies.” Measuring SEL: Framework Briefs. https://www.militarychild.org/upload/images/MGS%202022/WellbeingToolkit/PDFs/2_EI_Keeping-SEL-Developmental-CASEL.pdf.

Ho, J., & S. Funk. 2018. “Promoting Young Children’s Social and Emotional Health.” Young Children 73 (1): 73–79.

Kaspar, K.L., & S.L. Massey. 2023. “Implementing Social-Emotional Learning in the Elementary Classroom.” Early Childhood Education Journal 51: 641–50.

King, M. 2018. The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers. New York: Abrams.

NAEYC & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media. 2012. “Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8.” Joint position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/files/NAEYC/file/positions/PS_technology_WEB2.pdf.

Paciga, K.A., C. Donahue, K. Struble Myers, R. Fernandes, & J. Li. 2017. “Carrying Fred Rogers’ Message Forward in the Digital Age.” Fred Forward Symposium Proceedings. Latrobe, PA: Fred Rogers’ Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College.

Rogers, F. 2001. “A Point of View: Family Communication, Television, and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” Journal of Family Communication 1 (1): 71–3.

Rogers, F. 2019. Many Ways to Say I Love You: Wisdom for Parents and Children from Mister Rogers, 3rd ed. New York: Hachette Books.

Sharapan, H. 2012. “From STEM to STEAM: How Early Childhood Educators Can Apply Fred Rogers’ Approach.” Young Children 67 (1): 36–40.

Sharapan, H. 2015. “Technology as a Tool for Social Emotional Development: What We Can Learn from Fred Rogers.” In Technology and Digital Media in the Early Years: Tools for Teaching and Learning, ed. C. Donahue, 12–20. New York: Routledge; Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Whitmer, M., producer. 2004. Fred Rogers: America’s Favorite Neighbor [DVD]. Triumph Marketing.

Patricia A. Crawford, PhD, is an associate professor in the early childhood education program at the University of Pittsburgh. A former teacher of young children and a current teacher educator, her research focuses on early childhood, literacy, and children’s literature. She is the editor in chief of Early Childhood Education Journal. [email protected]