The Power of Child-Created Texts and Puppetry: Nurturing Preschoolers’ Social and Emotional Development (Voices)

You are here

An Introduction to Kiyomi Umezawa and Emiko Kurosawa Arakaki’s article

Barbara Henderson, Voices Executive Editor

Authors Kiyomi Umezawa and Emiko Kurosawa Arakaki explore how child-created texts enacted through puppetry nurtured preschoolers’ social and emotional development in the diverse Hawaiian setting where Emiko taught. This article also appears in the 2024 Voices of Practitioners compilation as part of a collection of pedagogical narratives where early childhood education professionals explore how stories from diverse media sources help foster inclusivity and amplify children’s agency. In this article, Kiyomi and Emiko reflect on their experiences as educators in Hawaiʻi, draw from their identities as recent Japanese immigrants, and surface their professional insights as teachers.

In working with these authors, I was struck by the profound inspiration they draw from pioneering teacher-researcher Vivian Gussin Paley. Like Paley, Kiyomi and Emiko emphasize the importance of honoring teachers’ and children’s voices through carefully told stories that share otherwise invisible truths. Like Paley, their use of narrative is twofold: the children’s stories are key to Emiko’s early childhood curriculum, and narrative is the genre they used to present this inquiry.

Overall, the authors’ work demonstrates the enduring relevance of Paley’s insights and gives voice to marginalized perspectives. Like all good teacher research, their collaborative efforts in researching and writing this article provided a space for their reflective practice, which meets the dual goals of improving their immediate work with children and sharing those insights with others.

Social and emotional learning is imperative for young children’s development. It helps them acquire and use the knowledge, skills, and mindsets needed to develop healthy identities, manage emotions, achieve goals, show empathy, build supportive relationships, and make responsible decisions (CASEL, n.d.-a.). Equitable early learning environments foster each and every child’s growth in these areas (Jagers, Rivas-Drake, & Borowski 2018).

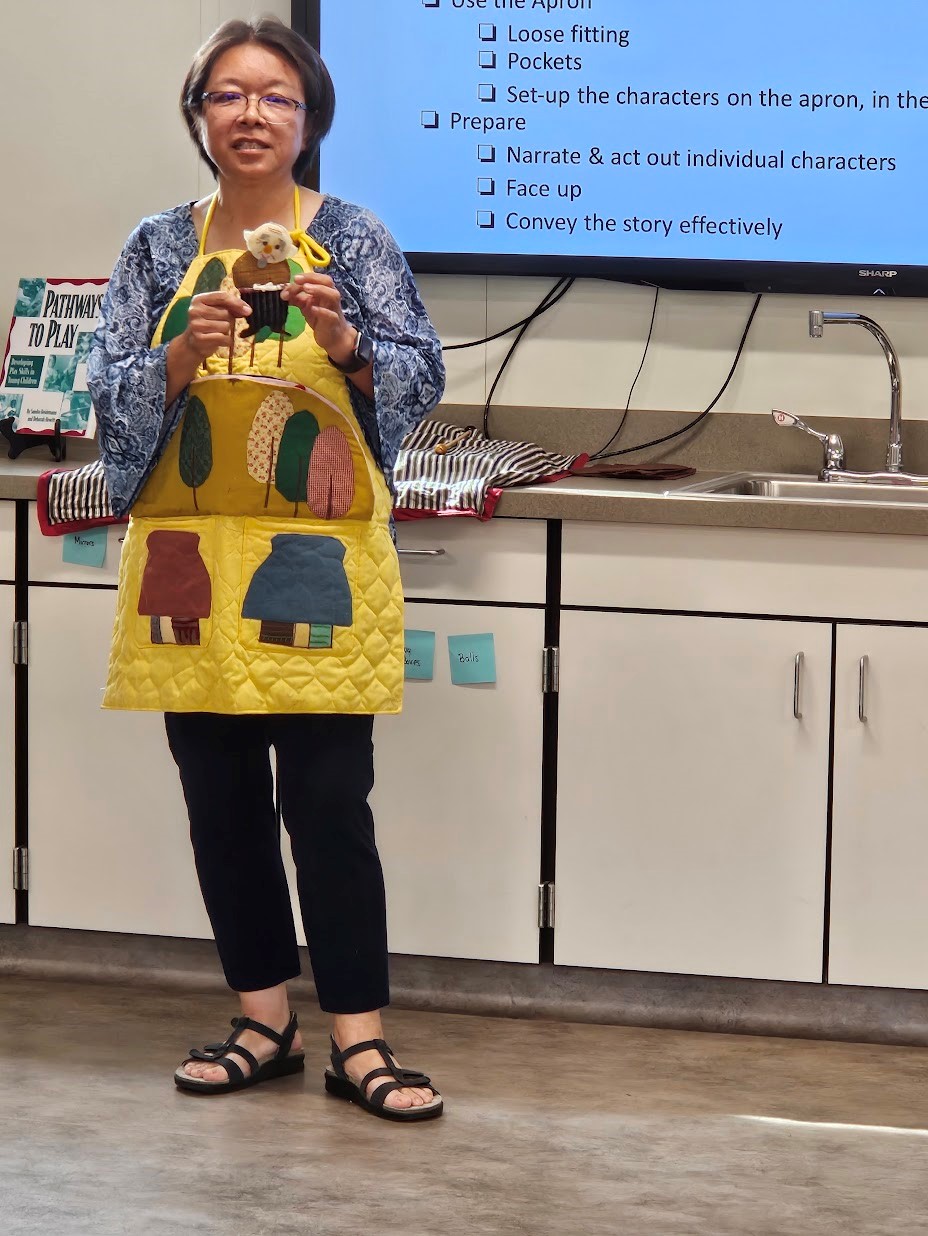

We (the authors) are educators in the state of Hawaiʻi. Emiko (the second author and pictured left, below) is a preschool assistant teacher, and Kiyomi (the first author and pictured right, below) is a former preschool teacher and current assistant professor of early childhood education. We met at the University of Hawaiʻi, where Emiko is a graduate student in early childhood education and where Kiyomi instructs. Our collaborative relationship evolved because we share several commonalities. Although we emigrated under different circumstances, we are both Japanese immigrants who came to Hawaiʻi as adults. Over time, we have learned about and reflected on the history of Hawaiʻi, its diverse cultural and linguistic landscape, and the lived experiences of those born and raised here, as well as those who immigrated here. Within this context, we each had to navigate assumptions based on our ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Our shared experiences have informed how we educate and care for young children and have encouraged us to see each of them as individuals developing within the contexts of their cultures and communities (NAEYC 2020). In this article, we share how Emiko supported the social and emotional development of two multilingual preschool children in her setting through a strengths-based approach. We describe how we collaborated on connecting Emiko’s knowledge of puppetry with research related to child-created storytelling and story acting and how she applied this knowledge to create an opportunity for the children to engage with each other and their peers.

Identifying and Responding to Children’s Social and Emotional Development

While working as an assistant teacher in a pre-K–12 private school, I (Emiko) taught children ages 3 to 5. The children represented a diversity of backgrounds that reflected Hawaiʻi’s demographics. Many children were of Asian heritage and had families who came from countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, the Philippines, and the Pacific Islands. In addition, there were children from the mainland United States and children whose families were from the Indigenous Polynesian people of the Hawaiʻi islands. The children varied in how long they and their families had lived in Hawaiʻi and included those who had recently immigrated with their families.

While working as an assistant teacher in a pre-K–12 private school, I (Emiko) taught children ages 3 to 5. The children represented a diversity of backgrounds that reflected Hawaiʻi’s demographics. Many children were of Asian heritage and had families who came from countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, the Philippines, and the Pacific Islands. In addition, there were children from the mainland United States and children whose families were from the Indigenous Polynesian people of the Hawaiʻi islands. The children varied in how long they and their families had lived in Hawaiʻi and included those who had recently immigrated with their families.

Our preschool program used a project-based learning approach: we planned and facilitated child-led learning experiences, and we learned alongside them. We also applied this approach in our after-school program, which the assistant teachers facilitated. While working in the after-school program, I noticed two 4-year-old children: a boy named Sean, whose family had recently relocated from Japan, and a girl named Ren, whose family had recently relocated from China. Both children were developing in their English-language speaking skills and exhibited various difficulties when communicating with the other children.

Ren was playful and highly energetic. She could speak some English but was not fluent and often struggled to express with words her desire to engage with peers. Instead, she often used actions to get their attention for the purpose of play. For example, at times, she snatched toys from the other children and ran away, inviting them to chase her. However, few children chose to interact with Ren, and worse, some blamed her when a negative event happened. During one incident when a child’s possession went missing, some of the children said, “Ren did it.” Soon after, I overheard her say, “I hate everyone.” Her statement struck and saddened me. Her strong emotional response prompted me to think of what I could do to support her. I knew, from working with other children, that she needed to have positive experiences with her peers. However, this was not something that I, as an educator, could give her without intentionally reflecting on the situation and planning for opportunities to foster her positive interactions with others.

Sean also had difficulty engaging with his peers. Like Ren, he was new to Hawaiʻi and did not speak English fluently. While he did play with his Japanese-speaking peers, he did not connect with the monolingual, English-speaking children. When his Japanese-speaking friends were not available, I observed that Sean didn’t interact with anyone. Some children enjoy solitary playing; however, I was concerned that Sean was playing alone because he did not feel confident in his English-language skills. I identified with this and wanted to show him that language skills were not everything—there were other ways to communicate and connect with peers. As with Ren, I knew that I would need to intentionally reflect on how I could support Sean.

Because my first language is Japanese, Sean and Ren’s experiences reminded me of the challenges I had faced living and working in primarily English-speaking spaces. I could see that they might benefit from guidance to learn social skills that would allow them to engage with their peers and promote their emotional growth. To do this, I intended to intentionally plan and scaffold social experiences that would help each child feel a sense of belonging as a member of our after-school community and draw on each child’s strengths and interests.

Leveraging Emiko’s Cultural Knowledge of Puppetry

Emiko shared her observations about Ren and Sean with me (Kiyomi), and we started to discuss how we could create a strategy to support the children’s social and emotional development and their relationships with other children. Thanks to what I had learned about Emiko during her time as a graduate student, I knew that puppetry and storytelling were two of her passions, so I suggested that she combine them with Vivian Gussin Paley’s notion of using storytelling and story acting to engage the children’s strengths and to promote a more equitable learning environment (Jagers, Rivas-Drake, & Borowski 2018).

Children explore the world and their place in it by creating stories, which we, the authors, view as a form of literacy (Rich 2002). Children’s stories can reveal valuable insights about their worlds and the knowledge they possess and can, therefore, serve as a basis for learning. Storytelling assists children in making sense of their surrounding environments and in imagining others’ environments, which is a process that contributes to the development of social awareness and cultivating relationships (Cremin & Flewitt 2017; CASEL, n.d.-b.). Vivian Gussin Paley’s work reflects these ideas. She was a kindergarten teacher and prominent teacher researcher who promoted children’s literacy and language learning and the importance of peer relationships. By explaining and implementing the rule “You can’t say you can’t play,” she created an inclusive environment for children who were emerging in social and emotional domains, had difficulty reading social cues, and tended to play alone by this rule (Paley 1992, 3). As educators, we can share why a rule like this exists in our own settings and discuss the importance of having empathy for others. It is crucial to provide learning opportunities for all children; finding ways for each child to belong can help to make them members of their learning communities.

Paley also proposed an approach called storytelling curriculum, in which teachers take dictations of children’s stories and then have the children act out their stories with peers. Researchers have delved into the influence of dictation and dramatization on children, especially in relation to literacy, and they have noted the effects on their own teaching. (To learn more about this, read Patricia [Patsy] M. Cooper’s “Understanding Vivian Paley as a Teacher Researcher” in the 2019 Voices of Practitioners compilation.) Though Paley’s focus was not on children’s cultural or racial identities, we concluded that we could extend her ideas about child-created texts to Ren and Sean’s participation in story acting and puppetry.

In the United States, puppetry is primarily viewed as a form of entertainment and is associated with children’s shows, theater productions, and amusement parks. However, in many Asian and European cultures, puppetry transcends entertainment and holds deeper cultural significance (O’Hare 2015). It can be a powerful medium for education, storytelling, and conveying complex emotions and ideas. Reflecting on our discussion, Emiko decided to introduce puppet making and storytelling activities to the children as a way for them to express themselves, build their peer relationships, and gain confidence. In the next section, we share how she went about doing this.

Creating a Shared Understanding Through Puppetry

One day, at the beginning of the school year, Emiko sees Ren in the dramatic play area making noodles by mixing yarn in a pot and Sean in the math area playing with manipulatives. She invites Ren to the math table where Sean sits. “You know, Ms. Emiko loves puppets,” she says, “Do you know puppets? They are like dolls but different; they have a special power.” She repeats this in Japanese for Sean. Intrigued by the idea, the children decide to make their own puppets. Emiko helps them look for materials—they find paper cups and pipe cleaners.

At first, the children communicate through Emiko, who translates Ren’s English to Japanese and Sean’s Japanese to English. Initially, Sean does not say much, but as they continue creating the puppets and their excitement grows, they communicate directly with each other using simple words, facial expressions, and body language. They eventually complete two puppets that they name Space Alien and Sparkle; Emiko invites Ren and Sean to tell her all about the puppets in a story. As Ren begins, Emiko takes dictation and translates for Sean. He adds more details, which Emiko translates to Ren. They continue this way until the tale is complete. When Emiko reads it back to them, Ren jumps up and down and Sean looks proud. Emiko notes that this is, perhaps, the first time she has seen him appear confident.

Storytime is scheduled to happen soon. Emiko suggests that Ren and Sean perform their story for the other children. They both enthusiastically agree. Emiko places a couch in front of the other children, and Ren and Sean sit behind it, giggling and holding their puppets tightly. Sean seems a bit nervous while Ren is hardly able to contain her elation. She stands up and peeks from behind the couch. All the children’s eyes are on her. Seeing her peers look at her with anticipation, she murmurs, “Wow.”

Emiko reads their story as Sean and Ren act it out.

Once upon a time, there was a boy named Sparkle. One time, Sparkle didn’t have a name, so he named himself Sparkle. Then he was walking around on the field, dancing around, hopping, hopping. Then one day, Sparkle was looking at the sky. Then he saw a space alien. Then the space alien came down to the earth and asked Sparkle, “Do you want to go to space?” Then Sparkle said, “Yes.” They went to outer space.

When the performance is finished, the children applaud. With a big smile, Ren says, “I love everybody!”

As shown in the vignette, introducing puppetry with storytelling helped Emiko foster a connection between Ren and Sean. While making the puppets, the two children invented their own ways to communicate. Their processes of puppet making and story making revealed insights into their understanding of relationships, stories, and play and enabled them to connect with others in their learning community. They witnessed the laughter and happiness their creations brought to the other children. This was their first time being in the spotlight, and they were accepted positively.

The positivity did not end there. As time went on, Emiko was able to observe the outcomes of this experience in facilitating Sean and Ren’s positive social interactions. She found that it helped them grow in the skills and confidence that would feed into future exchanges with each other and their peers. Through Ren and Sean’s collaboration, they established a shared understanding, which grows from the social exchanges required to engage in a mutually agreed upon framework (Guralnick 1993). In their case, creating puppets, a story, and putting on a show was their initial framework. After they acted out their story for their classmates, they went on to play Space Alien at the tree house. During this and subsequent interactions, they continued to negotiate which characters they would play in pretend scenarios and how the characters would behave. In addition to playing together in their favorite spot, the treehouse in the garden, they began to sit together at the snack table. Their shared understanding led to a successful peer relationship (Howes 1988) and enabled them to build social skills, such as establishing roles and rules.

In addition, Sean’s English language skills improved, yet he remained quiet when he played with Ren and tended to follow her lead. Because children of Asian heritage can be stereotyped as quiet, obedient, and polite (see Petersen 1966), some educators may, consciously or subconsciously, categorize someone like Sean as a quiet Asian boy. However, Emiko observed that after his experience with Ren, he displayed stronger leadership skills with his Japanese-speaking peers than he had previously; specifically, he talked more frequently and used a louder voice.

Reflecting on the Impact of a Positive Teacher-Research Experience

Because of my (Emiko’s) language barrier, cultural background, and position as an assistant teacher, I have not always been confident about expressing my educational beliefs, expertise, and intentions in the classroom. By observing, responding to, and reflecting on Ren and Sean’s interactions, I learned about them and myself as an educator. They demonstrated that I could implement puppetry as a tool for expression and to foster meaningful connections. My experience with Sean and Ren enabled me to start suggesting my ideas to other educators and to persist in advocating for the potential of child-created texts and puppetry in supporting children’s social and emotional development. I also learned how educators can become empowered through teacher inquiry and research (Zeichner & Noffke 2001).

Because of my (Emiko’s) language barrier, cultural background, and position as an assistant teacher, I have not always been confident about expressing my educational beliefs, expertise, and intentions in the classroom. By observing, responding to, and reflecting on Ren and Sean’s interactions, I learned about them and myself as an educator. They demonstrated that I could implement puppetry as a tool for expression and to foster meaningful connections. My experience with Sean and Ren enabled me to start suggesting my ideas to other educators and to persist in advocating for the potential of child-created texts and puppetry in supporting children’s social and emotional development. I also learned how educators can become empowered through teacher inquiry and research (Zeichner & Noffke 2001).

This example of applied practice shows the versatility of educators and children, the power of children telling their own stories, and the depth of puppetry as an art form. When we first began discussing and making plans to support Ren and Sean in developing peer relationships, we did not expect such positive outcomes. Their story hearkens back to Vivian Gussin Paley’s writing and practices, which contributed to the early childhood education profession’s understanding of her as the “consummate teacher researcher” (Meier & Stremmel 2010).

When educators have opportunities to engage in teacher research, they can take ownership as professionals, apply tools and approaches, and foster a sense of agency and leadership within their learning communities (Zeichner & Noffke 2001). This experience reinforces that teacher research in all forms is essential because it leads to improved teaching practices, addresses problems of practice (Stringer 2013), and ultimately enhances student outcomes by meeting their individual and diverse needs (Meier & Henderson 2007) and valuing their strengths (NAEYC 2020).

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- peruse an archive of Voices articles

- read the Winter 2023 Voices compilation

Photographs: header © Getty Images; other photos, courtesy of the authors

Copyright © 2024 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

References

CASEL (Collaboration for Academic and Social Emotional Learning). n.d.-a. “Fundamentals of SEL.” Accessed July 12, 2024. casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel.

CASEL (Collaboration for Academic and Social Emotional Learning). n.d.-b. “What is the CASEL Framework?” Accessed July 12, 2024. casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework.

Cooper, P.M. 2019. “Understanding Vivian Paley as a Teacher Researcher.” Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Teacher Education 14 (1).

Cremin, T., & R. Flewitt. 2017. “Laying the Foundation: Narrative and Early Learning.” In Storytelling in Early Childhood: Enriching Language, Literacy and Classroom Culture, eds. T. Cremin, R. Flewitt, B. Mardell, & J. Swann, 13–28. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Guralnick, M.J. 1993. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice in the Assessment and Intervention of Children’s Peer Relations.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education13 (3): 344–71.

Howes, C. 1988. “Peer Interaction of Young Children.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 53 (1): 217.

Jagers, R.J., D. Rivas-Drake, & T. Borowski. 2018. Equity & Social and Emotional Learning: A Cultural Analysis. CASEL Assessment Work Group Brief series. Chicago, IL: CASEL. casel.org/frameworks-equity/?view=true.

Meier, D.R., & B. Henderson. 2007. Learning from Young Children in the Classroom: The Art and Science of Teacher Research. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Meier, D., & A.J. Stremmel. 2010. “Narrative Inquiry and Stories—The Value for Early Childhood Teacher Research.” Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Teacher Education 12: 1–4.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents.

O’Hare, J. 2015. “Puppetry In Education and Therapy.” The Puppetry Journal 67 (1): 36.

Paley, V.G. 1992. You Can’t Say You Can’t Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Petersen, W. 1966. “Success Story, Japanese-American Style.” New York Times Magazine, January 9, 1966, 22. nytimes.com/1966/01/09/archives/success-story-japaneseamerican-style-success-story-japaneseamerican.html.

Rich, D. 2002. “Catching Children’s Stories.” Early Education 36 (6).

Stringer, E.T. 2014. Action Research, 4th ed. New York, NY: SAGE Publications.

Zeichner, K.M., & S.E. Noffke. 2001. “Practitioner Research.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching, 4th ed., ed. V. Richardson, 298–330. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Kiyomi Umezawa, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. She received a dual-title doctorate in curriculum and instruction and comparative international education at Pennsylvania State University. She is interested in the anthropology of educational language policy and multilingual education at the early childhood level.

Emiko Kurosawa Arakaki is an experienced early childhood educator and puppeteer. She earned an associate degree from Honolulu Community College and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Hawaiʻi at West Oahu. She is working toward a master’s degree in early childhood education at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. [email protected]