Focusing on Families: A Two-Generation Model for Reducing Parents’ Stress and Boosting Preschoolers’ Self-Regulation and Attention

You are here

Something special is happening in Head Start of Lane County, in Springfield, Oregon. While parents are learning to reduce stress and are enjoying more family time, children are developing the ability to regulate their emotions and direct their attention. At the same time, teachers and researchers are collaboratively developing a model of a two-generation program to share with early childhood educators across the country.

As Jenny Sonza, an experienced teacher who has been implementing the model for three years, explains, sometimes seemingly simple strategies make a big difference:

Zayna is a 3-year-old growing up in a stressful home. Her parents argue often, and the family had to leave their apartment because of trouble with lice and fleas. At Head Start, a normal day for Zayna begins with her screaming and crying because she wants her mother to stay, and ends with her being upset when her mother picks her up to leave. In order for Zayna to learn, whether it’s how to wash her hands or how to write her name, we have to get her stress level down.

In the morning, before Zayna’s mother leaves, we’ve been using a strategy called picture notes to help her calm down—this strategy is by far my favorite from the many we use with children. When Zayna starts screaming, I get a sticky note. But instead of writing a note for her, like “Mom will be back this afternoon,” I get down at her level and draw a little stick figure with her face. I say, “This is Zayna,” and she says yes. Then I draw her mom, and that really gets her attention. She says, “I don’t want my mom to leave.” I ask her, “What do you want?” and get her to focus on the note. Then we write the rest of the note together.

In the morning, before Zayna’s mother leaves, we’ve been using a strategy called picture notes to help her calm down—this strategy is by far my favorite from the many we use with children. When Zayna starts screaming, I get a sticky note. But instead of writing a note for her, like “Mom will be back this afternoon,” I get down at her level and draw a little stick figure with her face. I say, “This is Zayna,” and she says yes. Then I draw her mom, and that really gets her attention. She says, “I don’t want my mom to leave.” I ask her, “What do you want?” and get her to focus on the note. Then we write the rest of the note together.

Usually, Zayna tells me the note should say “I want my mom.” It’s that simple. I write, “I want my mom,” and she tells me what I wrote. Once the picture note is in her hands, she can let her mom leave. She knows that she wants her mom, she sees the note in her hand, she makes that connection, and her stress goes down instantly. She also knows that I (and my coteachers) see the note, that she is going to see it all day, and that we are all going to remember. Sometimes she puts the picture note in her cubby; other times she holds it in her hand.

Picture notes are just one of 20 strategies and activities teachers at Head Start of Lane County use to help children experience less stress and engage in the learning environment. In this article, we explain the many aspects of the child and family program we are implementing and evaluating—but first, let’s take a brief look at the research foundation for our approach.

High stakes and high hopes

Even before children enter school, their academic prospects can be predicted based on parental income, occupation, and level of education—the main factors that determine socioeconomic status (SES). While these are broad statistical generalizations that may or may not prove accurate for any given individual, disparities related to these factors have been documented in children’s cognitive skills and mental and emotional health, and in specific aspects of children’s brain structure and function. Disparities have been found to last into adulthood, impacting cognition, health, educational attainment, and financial stability (for reviews of the SES literature, see Hackman, Farah, & Meaney 2010; Ursache & Noble 2016). As a result, researchers and educators are strongly motivated to develop and implement evidence-based programs that can minimize these disparities. Increasingly, they are recognizing that their efforts can be informed by research in cognitive science and cognitive neuroscience (Shonkoff 2012).

Brain systems are changeable with high-quality preschool education, parental involvement, and other positive factors.

Importantly, we and other researchers who study the brain have found that neuroplasticity, or the changeability of the brain with experience, is a double-edged sword (Shonkoff 2012). That is, the brain systems that are vulnerable to negative experiences associated with differences in socioeconomic status are also changeable with high-quality preschool education, parental involvement, and other positive factors. Using these findings as a starting point, we developed a two-generation training program that improves preschoolers’ brain function for attention, as well as their cognition and behavior. It also improves parents’ communication skills and reduces family stress (Neville et al. 2013). The program focuses on two critical aspects of brain function: stress and self-regulation.

Stress

Some exposure to tolerable stress is an essential part of developing a healthy stress response system. However, stress may accumulate over time and become a burden if a young child experiences an excessive and/or prolonged activation of the stress response system in the absence of supportive adult caregiving. This cumulative burden can result in physiological disruptions that increase risk for a wide range of diseases in adulthood. Thus, chronic stress in child development is characterized as “toxic” (for a more detailed discussion of positive, tolerable, and toxic stress reponses, see Jack Shonkoff’s article in this issue; for a review, see McEwen & Gianaros 2010).

Executive Function

Executive function includes a diverse set of psychological processes, including core cognitive skills, such as inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, that emerge in infancy and undergo robust changes during childhood, with marked improvements observed between 3 and 5 years of age (Diamond 2013). The development of executive function has lifelong consequences; for example, good self-control in childhood predicts better health, less substance dependence, better personal finances, and less criminal offending in adulthood (Moffitt et al. 2011).

Decades of research indicate that children from families and communities suffering from the effects of lower income and fewer educational opportunities are more likely to grow up in homes that are more stressful and less cognitively stimulating than their more advantaged peers. On average, children in lower socioeconomic status homes experience more chaotic living conditions (e.g., crowding, noise, and family instability) and more inconsistent and harsh disciplinary practices than their higher socioeconomic status peers; these factors have been shown to account for up to half of the achievement differences associated with socioeconomic status (for review, see Hackman, Farah, & Meaney 2010). Also, poor sleep habits have been linked to poor academic outcomes in children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, on average, and family stress and inconsistency in the home environment have been identified as potential causes of poor sleep habits (Buckhalt 2011).

Good self-control in childhood predicts better health, less substance dependence, and better personal finances in adulthood.

The role of chaotic and stressful living conditions in children’s academic outcomes dovetails with an emerging literature in neuroscience. Human and animal studies indicate adverse effects of toxic stress on brain development—particularly development of the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, which are central to many facets of attention, working memory, executive function, emotional regulation, and learning (McEwen & Gianaros 2010). This suggests that stress that is chronically elevated by negative aspects of the home environment is one way some young children’s brain development may be compromised.

Self-regulation

Self-regulation is defined as controlling one’s attention, emotions, and executive functions (Blair & Raver 2015). Recent studies indicate that neural systems important for aspects of attention are particularly vulnerable in children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (e.g., Stevens, Lauinger, & Neville 2009). These newer studies build on a large body of evidence showing similar results regarding executive function in less advantaged children. Differences in systems such as working memory and inhibiting impulses may emerge as early as infancy and persist into adulthood (for reviews, see Hackman et al. 2010; Ursache & Noble 2016).

Many children who are behind in developing self-regulation also tend to struggle in school.

For educators, it will come as no surprise that many children who are behind in developing self-regulation also tend to struggle in school. Anything from paying attention to the teacher to completing a project could be a challenge. In terms of development of early math and literacy knowledge and skills among preschoolers, attention and executive function are more important than IQ (for a review, see Blair & Raver 2015).

Evidence-based training program: A two-generation approach

Converging evidence from multiple fields of study—including cognitive neuroscience, education, and economics—suggests that one of the most promising approaches to addressing these challenges is evidence-based training programs for young children from chaotic and stressful households (Neville et al. 2013). One effective approach is a two-generation model in which services focused on improving children’s school readiness and long-term outcomes are combined with services focused on increasing adult well-being. Studies initiated in the 1960s that tracked children into adulthood have shown that high-quality (and costly) programs directed toward preschoolers from disadvantaged backgrounds and their parents reduce many of the short- and long-term disparities noted in our research summary, ultimately paying for themselves many times over (e.g., Heckman et al. 2010). Similarly, studies of intensive home-visiting programs have shown that such programs improve cognitive and behavioral outcomes in children (e.g., Olds et al. 2004), and a review of international studies found interventions that include parent involvement to have the strongest effects on child outcomes (Burger 2010).

Drawing on this research base, we developed a program called Parents and Children Making Connections—Highlighting Attention (PCMC-A) through a nine-year collaborative partnership between the University of Oregon and Head Start of Lane County. PCMC-A is an eight-week program in which primary caregivers (referred to here as parents, since most caregivers were parents) attend weekly two-hour, small-group classes in the evenings or on weekends while, at the same time, their children participate in small-group training activities. The parent training, rooted in the pioneering work of the Oregon Social Learning Center, is designed to reduce family stress, while the child training is designed to improve attention and self-regulation, including emotional regulation. An evaluation of PCMC-A found positive results on multiple measures, including electrophysiological measures of children’s brain functions supporting selective attention, standardized measures of language and IQ, and parent-reported child behaviors. Similarly, parents participating in the program reported reduced parenting stress and displayed improvements in specific aspects of language interactions with their children (Neville et al. 2013).

Supporting children

PCMC-A’s child training consists of 20 activities developed by an experienced teacher, with input from Head Start of Lane County specialists. The activities target aspects of attention, including vigilance, selective attention, and task switching. (For Ms. Sonza’s description of some of the strategies in action, see “Reducing Stress, Increasing Learning: A Peek Inside Ms. Sonza’s Head Start Classroom,” on pages 28–35.) In each weekly session, children complete two to four of the activities in small groups (ideally four children with two adults). The program is structured around five core components:

- Positive social interaction, which involves practicing appropriate and positive interactions with others to support the child’s developing social skills

- Metacognitive awareness, which involves exercises to build the child’s awareness of different cognitive and emotional states, emphasizing emotional vocabulary to support emotional regulation development

- Self-regulation, which involves practice with self-directed strategies (e.g., deep breathing, self-redirection) to respond well to typical preschool stressors (e.g., delay of gratification, emotional overload)

- Focused attention, which involves exercises that naturally engage children so they experience and practice sustained focus on a selected stimulus

- Dealing with distractions, which complements and builds on the focused attention component with fun exercises to practice managing realistic classroom distractions

Throughout the training, instructional techniques include multisensory activities that purposefully move from guided tasks to independent practice, as well as from teacher directed to child directed, and activities that progress from simple to complex. One selective attention exercise, for example, involves engaging one group of children in coloring within the lines of detailed figures while ignoring the distraction of other children bouncing balloons in the air around them. Children alternate roles such that each child engages in both the coloring and the balloon activities. Over the course of the eight-week program, the distractions that children learn to disregard become more intense, which allows children to develop greater attention skills. The activities requiring focus and the distractions become increasingly similar to classroom situations, providing children with more realistic practice.

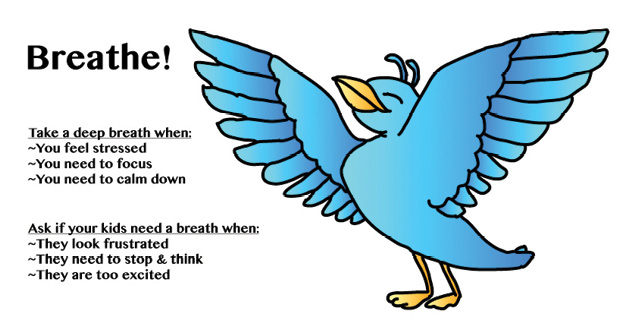

Activities also focus on increasing self-regulation of emotions. For example, in Emotional Bingo, children match words to convey emotions (e.g.,  happy, sad) with pictures of different facial expressions. This helps children learn emotional vocabulary and practice recognizing other people’s emotional states. In later sessions, practice in emotional awareness progresses to strategies for communicating emotions and eventually to strategies for self-regulation in periods of heightened emotions (e.g., take a deep “bird breath” to encourage calm, reflective actions instead of impulsive, reactive actions), with strategies reinforced by visual cues (e.g., a bird breath poster).

happy, sad) with pictures of different facial expressions. This helps children learn emotional vocabulary and practice recognizing other people’s emotional states. In later sessions, practice in emotional awareness progresses to strategies for communicating emotions and eventually to strategies for self-regulation in periods of heightened emotions (e.g., take a deep “bird breath” to encourage calm, reflective actions instead of impulsive, reactive actions), with strategies reinforced by visual cues (e.g., a bird breath poster).

Supporting parents

PCMC-A’s parent training consists of 25 strategies to reduce stress, which are delivered in small groups (to facilitate discussion and role playing) and supplemented with weekly support phone calls (to clarify activities to practice at home and offer more tailored suggestions based on parents’ experiences). The core of PCMC-A’s parent training includes nine components. The following five components were adapted from the Oregon Social Learning Center’s evidence-based programs for foster parents and for preventing conduct disorders among children (e.g., Fisher et al. 2000; Reid et al. 1999):

- Contingency-based home discipline, which teaches discipline strategies (e.g., time-out and privilege removal) that are closely related to the behavior that needs to be addressed

- Positive involvement, which emphasizes the benefits of encouraging appropriate behaviors (e.g., specific praise and/or specific noticing of children’s efforts, and success charts that break a routine or task into small, manageable steps and concretely reward each step)

- Skill encouragement, which helps parents appreciate, support, and reward children’s development (e.g., again, breaking behavior into small steps and using praise and incentives appropriately)

- Problem solving, which emphasizes the value of offering children choices so that they learn to make decisions and their parents learn that well-framed choices decrease conflict

- Monitoring and supervision, which provide structure and safety, and allow for healthy development

In addition, PCMC-A’s support for parents includes four unique components:

- Age-appropriate communication, which encourages parents to engage their child using clear and meaningful statements and requests and to use pictures to supplement communication

- Emotional regulation, which promotes awareness of the child’s emotional states (e.g., emotional overload) and provides strategies to support the child’s developing emotional regulation skills

- Family stress management, which provides strategies to help parents prevent, manage, and reduce stress in the household (e.g., the creation of predictable home environments, awareness and avoidance of power struggles) and also includes lessons on the impact of chronic stress on brain development

- Child attention and self-regulation support, which encourages parents to support the child’s emerging attention and self-regulation skills via strategies (e.g., giving the child opportunities to make choices and solve problems in a variety of situations) and via the sharing of strategies and materials from child-attention training activities to facilitate application in the home

Throughout the program, improving communication between parents and children is critical—and very carefully planned. For example, strategies for improving the degree to which children attend to parent language begin with an activity in which parents are asked to increase their awareness of the language they use when communicating with their children. This includes monitoring how much positive language they use, such as how often they offer specific (as opposed to general) praise for their children. It also draws attention to how much negative language they use and the possibility of emotionally overwhelming their children. Once parents understand the importance of positive interaction, they are taught strategies for providing specific praise and specific noticing to increase their children’s self-confidence.

Other strategies emphasize reducing overall stress by boosting predictability for the child through an increase in consistent home routines. For example, parents are encouraged to implement structured routines with picture-based schedules (success charts). Across the program, there is a hierarchical progression from establishing more focused routines (e.g., bedtime) to fostering child-directed daily and weekly schedules.

In addition, parents receive information on the attention activities their children are engaging in, with ideas for how to provide further practice at home. For example, to facilitate practice of the bird breath strategy to help children breathe deeply to cope with strong emotions, parents are given a bird breath poster and encouraged to display it at home as a visual reminder for both themselves and their children.

Conclusion: Supporting more families

The collaboration between Head Start of Lane County and the University of Oregon has been fruitful—and is ongoing. We are currently developing, implementing, and assessing a scaled-up delivery model of Parents and Children Making Connections—Highlighting Attention that can be more easily integrated into existing Head Start services across the country. In this revised delivery model, titled Creating Connections: Strong Families, Strong Brains, the child training is integrated into Head Start classrooms and delivered across the school year. In addition, selected strategies from the parent training are now integrated into the classroom. These include strategies for using enhanced language with children, such as specific praise and noticing, clear statements, and specific metacognitive (“thinking”) vocabulary, as well as strategies to improve consistency and predictability through schedules, routines, and calendars. We hypothesize that introducing children to these strategies in the classroom will permit children to become familiar with them before their parents try them at home, which should lead to greater success for parents. We also hypothesize that greater integration between classroom and home will increase consistency and predictability for children and lead to greater reductions in stress.

As we study Creating Connections, we are also expanding our measures of family stress and self-regulation beyond those used in our previous study (Neville et al. 2013). We now assess changes in brain functions that support selective attention in both children and their parents, as well as changes in heart rate variability, a measure that is a good indicator of stress. These measures are acquired simultaneously, capturing the dynamic interaction between heart and brain. Finally, to determine whether this two-generation model might result in broader improvements related to family well-being, we also analyze Head Start measures, including evaluations of parents’ educational attainment and goals, employment, financial literacy and stability, community connections/support, and health and safety (including access to health care, housing, and child care).

While Creating Connections is not yet available for wider implementation, research from our lab and others suggests that curricula involving aspects of attention, self-regulation, and social and emotional learning are likely to prove beneficial in preschool settings. In addition, efforts to increase parent engagement, particularly in ways that are integrated with classroom materials and/or support children’s emerging attention, self-regulation, and emotional regulation skills, may provide benefits beyond those from classroom curricula alone.

Reducing Stress, Increasing Learning: A Peek Inside Ms. Sonza’s Head Start Classroom

Jenny Sonza has been a teacher with Head Start of Lane County, Oregon, for 11 years. This is her third year working with researchers from the University of Oregon to implement the two-generation model. Ms. Sonza cherishes the deep connections she makes with families through the program and sees great reductions in family and child stress when the strategies she uses in the classroom are also taught to parents and used at home. This year, she has two coteachers and 18 students who range from 3 to 5 years old (though most are 3). Through the following vignettes, we see the difference the two-generation model makes for the children. (Throughout the vignettes—here and in the article—children’s names have been changed.)

—Editor

Luna Waits Her Turn

Picture notes work well in a variety of situations. For example, when a child wants a turn with the Legos but has to wait, I draw and write a note to help the child understand that I know he wants a turn and to remind him when he will have a turn. We have picture notes all over the classroom. They let children know that they have been heard, give them a sense of control, and help them remember what’s going to happen later in the day or week.

Luna is a 4-year-old who needs a picture note almost every day to help her wait for her turn on the computer. Most mornings, Luna comes in and wants to use the computer right away, expressing herself through a temper tantrum. As I ask her what’s going on, I draw a picture of her and the computer on a sticky note, and then I tell her, “This is Luna, and this is the computer.” When I have her attention, I ask, “When is your turn on the computer?” Together, we look for her name on the computer schedule. And then I help her express it: “Oh, well, it’s not today, Luna. Hmm. What is your day?” She sticks the picture note on the calendar to remind herself when her turn is. Still, Luna will come up in 15 minutes and say, “I want the computer. I want the computer. I want the computer.” And then I’ll say, “Oh gee, Luna, when is your computer time? Hmm. Let’s go look on the calendar.” We’ll walk back over and look at her picture note. Luna rarely starts another temper tantrum; she just wants confirmation.

Sometimes when Luna returns from checking her turn on the calendar, she is upset; so we’ll make another picture note about her feelings. I’ll ask, “How does that make you feel?” Usually she’ll say “mad,” and one of us will draw a mad face. Sometimes I also write “Luna is mad because she has to wait.” Usually after this second note, she won’t ask again that day. Helping children recognize and acknowledge their feelings is a great way to deescalate stress.

Logan Sits Tight

One thing I love about picture notes is that they are so adaptable and personal for each child. Once children grasp the concept, they will start dictating, drawing, and writing picture notes for themselves and others. Sometimes the 5-year-olds draw picture notes that function just like adults’ notes. I had a 5-year-old with an elaborate plan for building something, but not all the pieces he wanted to use were available at that time. So, he drew a series of notes to remind himself which pieces to gather up as other children finished with them. It was a great step in his budding literacy development.

As part of the two-generation program, we also teach parents to use picture notes at home. When we do it in the classroom and families do it at home, children respond really well. Consistency is key. Parents are amazed at how their children’s stress goes down—and then positive interactions go up.

Picture notes were a lifesaver for one family. They had a new baby, and their 3-year-old was jealous. His way of acting out was to dart out of the parked car and run toward the street. You wouldn’t think a picture note would help with something like this, but it did. His mom drew a note that said “Logan, look where we are going.” Logan would stop, look at the note, and think. He held the picture note in his hand, and focused on it. It was magic; it worked every time for Logan. It seemed like his real objective was to get attention from his mother, and this note represented both her at tention and a tool to help him refocus on where they were headed.

tention and a tool to help him refocus on where they were headed.

Once a picture note works for you, it is amazing. It doesn’t seem possible to take a child’s stress from a 10 to a 2 with just a couple of stick figure drawings. Yet, for most children, it works. Of course, it doesn’t always work. There are children who will tear up the note. But it is worth trying. Your initiative and attention in drawing the note and handing it to the child helps her feel valued and heard. Children like having the picture note in their hands. They hold it; it’s proof, and it helps them remember. That, in turn, keeps their stress from going back up.

Jaden Takes a Bird Breath

Deep abdominal breathing is an important strategy for children to learn. “Deep belly breaths,” as we call them in class, are great for calming the body. We usually start with teaching a “bird breath.” We have bird breath posters in the classroom, and we also give them to parents. School and home consistency makes a big difference! Since we have three teachers in the classroom, one goes to the poster and the others stay near the children to model for them. I usually say to the children, “While your arms, which are your wings, are going up all the way to the top of your head, you are breathing in. When your wings are vertical, straight to the sky, you’re going to suck in that last breath. And then your wings flap all the way down—flap, flap, flap—and the bird is out of breath.” I make sure the children can hear me breathing out. When they flap their wings down, they have to breathe out. If you try it, you’ll feel how flapping your arms pushes air out. And then we do it again, sometimes three, four, or five times.

e do bird breaths to calm down at circle time, before meals, when we’re in line. Last year we combined teaching about bird breaths with a story about an owl. So when the children breathed out, they made the owl’s “hoo, hoo, hoo” sound, which helped them exhale. But every class is different—this year, the owl story didn’t work because the children made many different noises, several of which were not conducive to breathing out. We were not accomplishing our goal of calming the body, so we had to stop using the bird noises to focus on breathing deeply in and out. But we’re still bringing our arms up and flapping them down.

And it’s still working! Recently, at meal time Jaden said, “Ahhh—I thought it was pizza not enchiladas!” and started jumping around. I said, “Oh, what can we do? Can we calm our body down?” And another child said, “Yeah, calm your body down. Take a bird breath.” Jaden said, “Well, okay,” and everyone else chimed in, “Yes! Let’s take a bird breath!,” like they were having a good time. And then everyone took that bird breath together. Jaden only did it halfway, but he got pulled into the class’s de-escalation and felt better.

It’s wonderful to see the children helping each other learn self-regulation. Often, as a child starts to get mad, another will say, “Take a bird breath.” The children want to help each other; when they have these strategies, they can. The strategies are at their level, so they don’t always have to ask a teacher for help.

Mateo Zooms In

Once children have practiced picture notes and deep belly breathing to reduce stress, we help them learn to pay attention and ignore distractions. It is important to work on de-escalation techniques first—otherwise, they don’t have strategies for dealing with the stress that distractions can cause.

The model’s curriculum has some fun ways for children to practice ignoring distractions. One is to walk on a string that’s taped to the floor while holding something on a spoon. The challenge is not just paying attention to both the string and the spoon—it’s also ignoring the other children, who are intentionally doing distracting things, like beating drum sticks on the ground. My class is taking time to build up to that. We’ve started with walking on a string to go wash our hands while ignoring the natural distractions in the classroom.

With a class that’s at least half 5-year-olds, teachers plan elaborate distractions, like “Guess what! Ms. Ayana’s class is going to come in with a parade and we’re going to ignore them. We’re going to breathe, and if we can ignore them, we’ll get a bubble party.” These activities are always swapped, so each class will parade and practice ignoring the distraction. With my class of mostly 3-year-olds, we’ve done simpler things, like having one half of the class jump while the other half ignores them.

In addition to breathing, one strategy we teach the children is to put their blinders on by putting their hands up by their eyes (like horse blinders). This really helped 3-year-old Mateo. During circle time recently, I asked the children to focus on one of my coteachers, who was reading a story. But there were a few kids who were not paying attention. While I was trying to redirect them, they were moving around and serving as a natural distraction for the other children. So I told the other children to put on their blinders and look at the teacher reading. We teach children to make blinders, and we explain that it is a way to reduce their peripheral vision and ignore distractions. For Mateo, blinders are not enough. He prefers to use his hands to make binoculars—a strategy we teach to focus attention. With his binoculars, Mateo zooms in on the teacher.

Blinders work especially well when we do deep belly breathing first. Breathing calms the children, gets them focused on their bodies, and prepares them to direct their attention. The blinders are an extra tool that works for most of the class when a few children are taking more time to settle down.

It’s important to teach these strategies for staying calm and ignoring natural distractions, because that’s what children have to do in order to learn. With eighteen 3- to 5-year-olds in a classroom, there is always a lot going on. We can’t let that prevent children from hearing the story or engaging in any other learning.

Changing Brains: Free Short Videos That Explain How Experiences Affect Brain Development

Throughout life, our brains change as a result of our experiences. While our brains remain adaptable—so learning and growth are possible—early childhood is a particularly important time. In the “Changing Brains” series of free, 2- to 10-minute videos (available at http://changingbrains.org/watch.html), leading researchers explain the keys to healthy brain development in 11 critical areas:

- Brain plasticity

- Imaging/development

- Vision

- Hearing

- Motor system

- Attention

- Language

- Reading

- Math

- Music

- Emotions and learning

- Math

References

Blair, C., & C.C.Raver. 2015. “School Readiness and Self-Regulation: A Developmental Psychobiological Approach.” Annual Review of Psychology66: 711–31.

Buckhalt, J.A. 2011. “Insufficient Sleep and the Socioeconomic Status Achievement Gap.” Child Development Perspectives 5 (1): 59–65.

Burger, K. 2010. “How Does Early Childhood Care And Education Affect Cognitive Development? An International Review of the Effects of Early Interventions for Children From Different Social Backgrounds.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25 (2): 140–65.

Diamond, A. 2013. “Executive Functions.” Annual Review of Psychology 64: 135–68.

Fisher, P.A., M.R. Gunnar, P. Chamberlain, & J.B. Reid. 2000. “Preventive Intervention for Maltreated Preschool Children: Impact on children’s Behavior, Neuroendocrine Activity, and Foster Parent Functioning.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39 (11): 1356–64.

Hackman, D.A., M.J. Farah, & M.J. Meaney. 2010. “Socioeconomic Status and the Brain: Mechanistic Insights From Human and Animal Research.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11: 651–9.

Heckman, J.J., S.H. Moon, R. Pinto, P.A. Savelyev, & A. Yavitz. 2010. “The Rate of Return to the HighScope Perry Preschool Program.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (1–2): 114–28.

McEwen, B.S., & P.J. Gianaros. 2010. “Central Role of the Brain in Stress and Adaptation: Links to Socioeconomic Status, Health, and Disease.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (1): 190–222.

Moffitt, T.E., L. Arseneault, D. Belsky, N. Dickson, R.J. Hancox, H. Harrington, R. Houts, R. Poulton, B.W. Roberts, S. Ross, M.R. Sears, W.M. Thomson, & A. Caspi. 2011. “A Gradient of Childhood Self-Control Predicts Health, Wealth, and Public Safety.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (7): 2693–8.

Neville, H.J., C. Stevens, E. Pakulak, T.A. Bell, J. Fanning, S. Klein, & E. Isbell. 2013. “Family-Based Training Program Improves Brain Function, Cognition, and Behavior in Lower Socioeconomic Status Preschoolers.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (29): 12138–43.

Olds, D.L., H. Kitzman, R. Cole, J. Robinson, K. Sidora, D.W. Luckey, C.R. Henderson Jr., C. Hanks, J. Bondy, & J. Holmberg. 2004. “Effects of Nurse Home-Visiting on Maternal Life Course and Child Development: Age 6 Follow-Up Results of a Randomized Trial.” Pediatrics 114 (6): 1550–9.

Reid, J.B., J.M. Eddy, R.A. Fetrow, & M. Stoolmiller. 1999. “Description and Immediate Impacts of a Preventive Intervention for Conduct Problems.” American Journal of Community Psychology 27 (4): 483–518.

Shonkoff, J.P. 2012. “Leveraging the Biology of Adversity to Address the Roots of Disparities in Health and Development.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (Supplement 2): 17302–7.

Stevens, C., B. Lauinger, & H. Neville. 2009. “Differences in the Neural Mechanisms of Selective Attention in Children From Different Socioeconomic Backgrounds: An Event-Related Brain Potential Study.” Developmental Science 12 (4): 634–46.

Ursache, A., & K.G. Noble. 2016. “Neurocognitive Development in Socioeconomic Context: Multiple Mechanisms and Implications for Measuring Socioeconomic Status.” Psychophysiology 53 (1): 71–82.

Photographs: 1-5, © Matt Barnhart; 7, © iStock;6, poster courtesy of Christina M. Karns

Eric Pakulak, PhD, is the acting director of the Brain Development Lab at the University of Oregon, in Eugene. His primary research interests are the neuroplasticity of brain systems important for language and attention and the development of evidence-based training programs for families. [email protected]

Melissa Gomsrud, MA, LPC, NCC, is a family interventionist in the Brain Development Lab and has a private practice providing mental health services. She has served and supported vulnerable families for over 20 years. [email protected]

Mary Margaret Reynolds, MDiv, is a regional manager with Head Start of Lane County, in Springfield, Oregon, where she is liaison with the Brain Development Lab Creating Connections Project and coordinator of the parent training program. Mary works extensively with dual language learners. [email protected]

Theodore A. Bell, PhD, is a research associate in the Brain Development Lab. He has conducted research on memory, attention, and interventions designed to benefit child self-regulation and attention. [email protected]

Ryan J. Giuliano, MS, is a doctoral researcher in the Brain Development Lab. Ryan’s research examines EEG measures of brain function and cardiac measures of stress physiology in young children and their parents. [email protected]

Christina M. Karns, PhD, is a research associate in the Psychology Department at the University of Oregon. In her work with the Brain Development Lab, Christina works at the intersection of development, attention, neuroplasticity, and neuroimaging. [email protected]

Scott Klein, MS, is a licensed teacher and practicing family therapist at Oregon Community Programs. Scott is a primary developer of Brain Train and helped adapt PCMC-A for Spanish-speaking families and for the recent implementation in Lane County Head Start. [email protected]

Zayra N. Longoria, PhD, is a family counselor for the F.A.I.R. Program at OSLC Developments Inc., in Eugene, Oregon. Zayra has extensive experience implementing evidence-based family interventions that promote social, cognitive, and affective competence in children and strengthen parent–child relationships. [email protected]

Lauren Vega O’Neil, MEd, MS, is a developmental cognitive psychology doctoral student at the University of Oregon. She is a former educator with 10 years of experience in general education and English as a Second Language. Some research interests include language acquisition and neuroeducation. [email protected]

Jimena Santillán, MS, is a doctoral candidate in the cognitive neuroscience program at the University of Oregon and a graduate research assistant in the Brain Development Lab. Jimena has delivered PCMC-A’s child training and parenting training.

Helen Neville, PhD, is the director emerita of the Brain Development Lab. She is internationally recognized for her research on the plasticity of the developing brain, is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and has received numerous awards for this work.

[email protected]