Research News You Can Use: Debunking the Play vs. Learning Dichotomy

You are here

The Director of the NAEYC Center for Applied Research examines the tension between play and academic achievement in early childhood education.

The November 2011 issue of Scientific American Mind includes the provocatively titled article “The Death of Preschool.” The online version carries a different title: “Preschool Tests Take Time Away from Play—and Learning.” Both titles are a bit misleading. In fact, enrollments in preschool and prekindergarten programs have been rising for the past decade or so; by this measure, at least, early childhood programs are thriving. Likewise, while assessments do take some time away from other activities, they do not necessarily limit play or learning. What the author of the article, Paul Tullis, is really concerned about is the ongoing pressure against play as a valued component of early childhood education and the increasing focus on academic achievement and preparation for standardized tests. Tullis gives us, in a few pages, a broad overview of the pressures faced by preschool teachers caught in a tug-of-war between direct instruction and play to nurture the school readiness of young children.

It is not play versus learning, but play and learning

The tension between play and direct instruction during the preschool years is as puzzling as it is real. Many (including NAEYC) argue that it is a false dichotomy—that both direct instruction and play have roles to play in high-quality early childhood education. As Tullis points out, the science behind play, what exists, should be sufficient to argue at least for its inclusion, if not a focus, in early education. But in the face of increased pressure on literacy and mathematics, driven in part by the No Child Left Behind Act and development of the Common Core Standards, policy-makers and some parents are expecting preschool programs to look more like classrooms for older children. They believe direct instruction is the way to meet these expectations.

What do we want for young children?

Is preparing children to meet performance expectations in third grade all that is valuable in early education? Tullis looks at a pair of studies published a year ago (summarized here; originals can be found here and here). Both studies compared children’s behavior when provided with direct instruction (of a sort) about how to activate a novel toy, and when allowed to explore the toy without explicit instruction (a sort of free-play condition). The results? The children given direct instruction learned the intended use of the toy. Ultimately, the children in the free-play condition did so, as well. But the children in the exploration groups also discovered additional uses of the toy or its pieces. The authors concluded that this group showed creativity and problem solving skills not necessary in the direct instruction condition. What is striking, though, is an unspoken reality: We want children to be both knowledgeable about facts and details and be creative and good problem solvers. We want young children to know that 2 + 2 = 4, but also use that knowledge across a range of situations beyond answering a single test item. Shouldn’t that mean there is a place for both direct instruction and play?

Splitting the dichotomy

Splitting the dichotomy

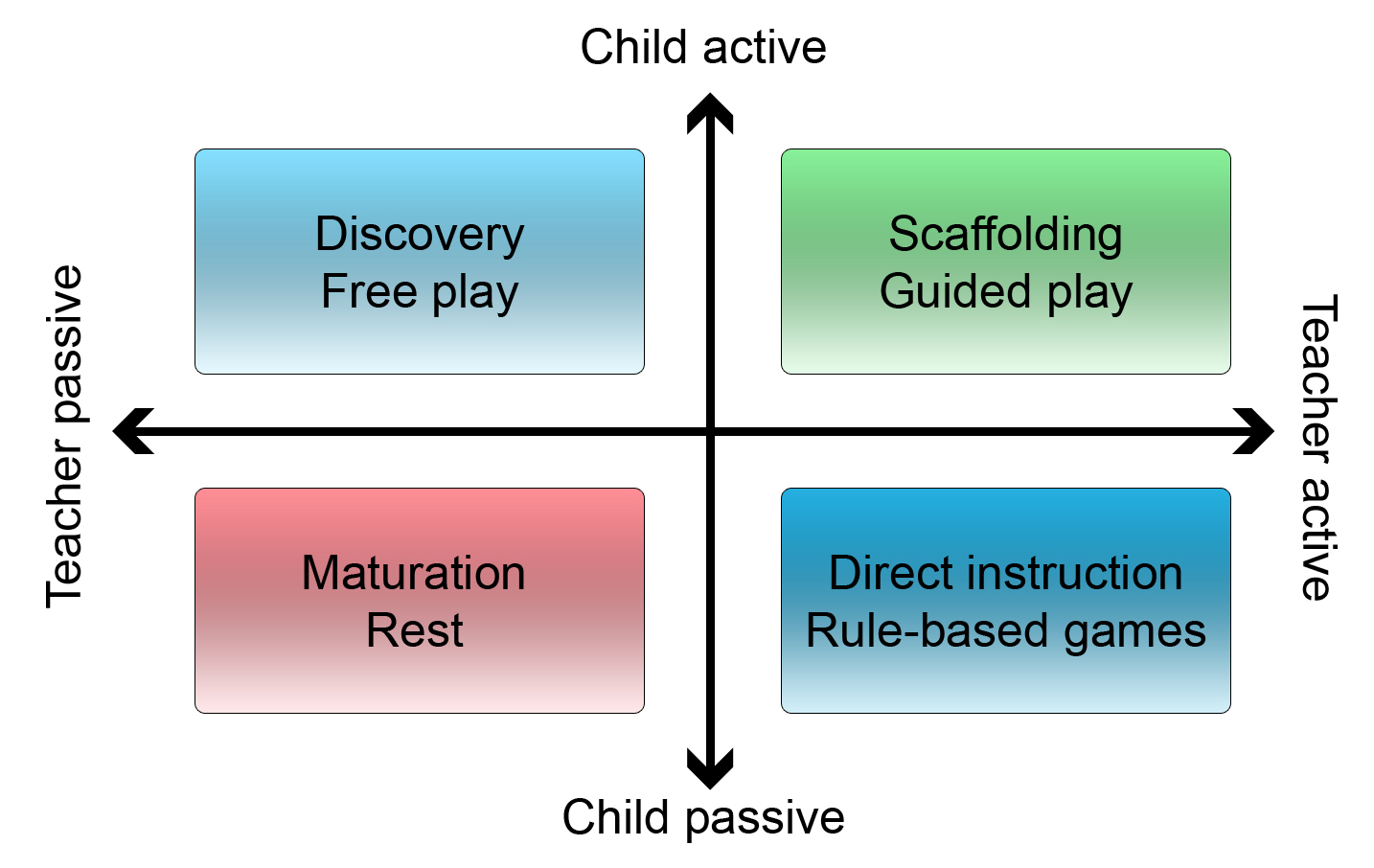

One response to the tension between direct instruction and play is to find middle ground. Kathy Hirsh-Paseck and her colleagues, in The Mandate for Playful Learning, stress that learning occurs through play and argue that a play-based early childhood program can support the same skills valued in programs taking a more direct instruction approach. Another strategy for finding the middle ground between play and direct instruction is to view instruction and play as two ways of defining activity in classrooms. In the session “Making Play Work” at the 2011 NAEYC Annual Conference and Expo, I presented this strategy using the figure above. In it, the degree of child activity and teacher activity are mapped onto each other. The resulting four quadrants show the overlap between teacher instructional strategies (as more or less actively directing) and child play activities. Both of these approaches challenge us to think about the roles of teacher and child, and of play and instruction, in more complex and more intentional ways.

Where do we go from here?

While it can be provocative to think about the apparent conflict between play and instruction, how does this help us meet the needs of young children? The principles of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) guide us to intentionality through understanding child development generally, each child’s developmental level specifically, and the larger social and cultural context the child lives within. We can use DAP to guide us to the best uses of play and direct instruction in early childhood classrooms. NAEYC has developed DVD-based programs for implementing play and DAP. At the same time, research on play and learning is still in its infancy. Research is just beginning to show how best to balance play and instruction to nurture each child’s development in all the ways that are important for them. What is clear is that maintaining the dichotomy between play and instruction is a distraction. We need to turn away from an either/or view, to the more complex challenge of balancing them together.