Inquiry Is Play: Playful Participatory Research (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Barbara Henderson, Voices Executive Editor

Megina Baker and Gaby Davila’s article is an example of teacher research coauthored by a university researcher and a teacher. Baker and Davila share several outcomes of teacher research they undertook at an international school in Denmark. One key aspect of this study sets it apart from other articles we have published in Voices of Practitioners: it focuses on a new research methodology, playful participatory research (PPR). This new methodological approach adds to our understanding of how teacher research can be undertaken, and it provides a new set of tools to prompt, guide, and deepen teachers’ collaborative inquiry.

As a methodological piece, Baker and Davila devote a good deal of their article to defining and describing this new model of research. They also compare PPR with the existing tradition of participatory research, focusing on what makes this new method playful and how that playfulness impacts teachers’ sense of self and connections to others. This online version includes an additional reflection from the authors showing how the defining elements of PPR—playful provocations, playing with roles as teachers, and playful collaborations with children—transform participatory research into a vehicle for shared learning for teachers and children alike.

The teacher-researchers in the Playful Environments Study Group—15 early childhood educators in all—are gathered for their monthly group meeting. This meeting feels special, as the group is together in the Kindergarten Creator Space, a new makerspace for children ages 3 to 6 that the teachers have envisioned, planned, and created in partnership with university researchers. The meeting, planned collaboratively by two members of the study group, begins with a “gallery walk” to view the teachers’ documentation of their classes’ first visit to the new room and how the children interacted with the space and materials.

As teachers view their colleagues’ documentation, they jot thoughts on sticky notes to respond to two prompts:

- Based on the documentation, what aspects of the Kindergarten Creator Space seem to support learning through play?

- What aspects seem to hinder learning through play, and what could we do to change that?

Rather than posting their comments on a board, the facilitator suggests that the teachers stealthily hide their sticky notes somewhere in the room so their colleagues have to search for them—and in the process, explore the new space in a novel, playful way. On a cue from the facilitator a few minutes later, the teachers begin to look around the room for the sticky notes their colleagues have hidden, laughing and joking with each other: “I bet you can’t find mine!”

The search has elements of silliness, but it also encourages teachers to learn about the materials in the new room, sometimes even getting down at the children’s level to search and explore from different angles. “I didn’t know we had so many beads—I could use these for our color unit,” one teacher remarks, finding one of the sticky notes on a shelf of loose parts materials. The note reads, “Coming out of the classroom seems to support learning—this room has a calm feel.” Another teacher kneels down, looking behind a mirror set at child height in a corner, and notices that she can see more of the room than she expected from that low angle.

When all the notes have been found, the group gathers in a circle to read through the ideas and have a discussion about how to improve the space to best support learning through play. Ideas include developing ways to support children who struggle with the wide array of available materials (such as preplanning to select a smaller group of materials) and creating a set of shared norms for the use of the Creator Space.

What’s going on here? Were teachers just playing hide-and-seek during a research meeting? Yes! Many of the participants recalled this hide-and-seek experience as both purposeful and playful, as it cultivated a playful mindset and allowed them to think about the Creator Space in an open-ended and novel way. This is one of many purposefully playful experiences teacher-researchers at the International School of Billund in Denmark are having as they engage in playful participatory research (PPR).

Through the Pedagogy of Play (an initiative of Project Zero, a research institute at the Harvard Graduate School of Education) teacher-researchers and university-based researchers are collaborating on PPR as a new form of teacher action research. Megina (the first author) is a university-based researcher, and Gaby (the second author) is an early childhood educator at the International School of Billund. Together, we are representing the work of the Pedagogy of Play research collaboration. In this article, we explain what PPR is and why it can be a valuable research approach, and then offer an example of how a group of early childhood educators engaged in a PPR process to envision and create a makerspace for young children.

We join with many other scholars who have argued that more teacher research is needed so that the voices of practitioners can be heard contributing to—not just digesting—research recommendations for teaching and practice (Cochran-Smith 2012; Perry, Henderson, & Meier 2012; Escamilla & Meier 2018). By “teacher research,” we mean research that is “conducted by teachers, individually or collaboratively, with the primary aim of understanding teaching and learning in context and from the perspectives of those who live and interact daily in the classroom" (Perry, Henderson, & Meier 2012, 4). But so many factors can get in the way of teachers actually engaging in research. When we speak with educators about the barriers to becoming teacher-researchers, they often say, “There just isn’t enough time!” or “But I’m a teacher, and my focus is on the classroom; research isn’t for me.” We see PPR as a process that can bring forward more teachers’ voices. In PPR, teachers do not only meld their research with real, engaging issues they are already thinking about in their teaching, but they engage playfully in this research with colleagues and children, making the experience energizing, fulfilling, and, well, playful (Baker et al. 2016).

What is playful participatory research?

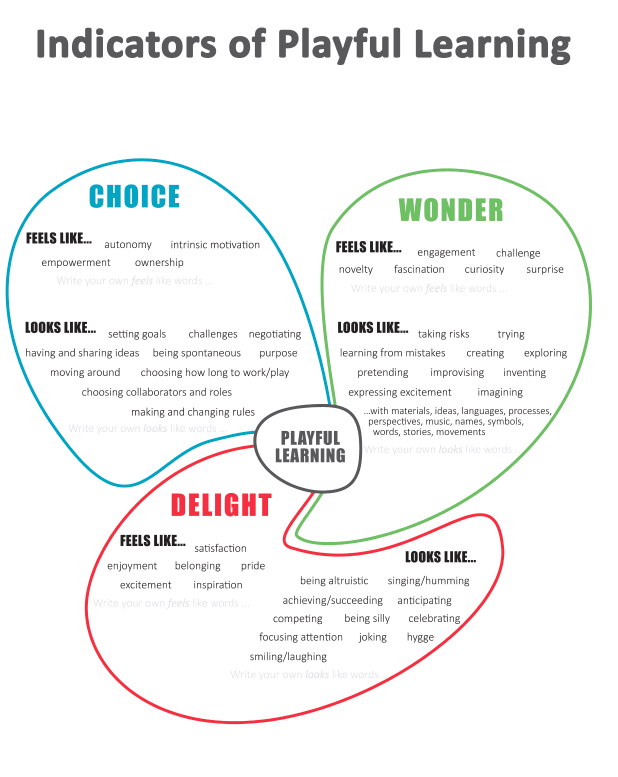

Let’s begin by unpacking what PPR is and how it connects to other teacher research and action research traditions. PPR is grounded in a large body of theory and research that demonstrates the value of play and playfulness as vehicles for learning (Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2009; Frost, Wortham, & Reifel 2012; Mraz, Porcelli, & Tyler 2016). In our broader work within the Pedagogy of Play initiative, we describe learning through play in schools as an experience in which learners have choice and agency, feel a sense of wonder or curiosity, and experience delight or satisfaction in the learning process (International School of Billund n.d.). PPR shows that play and playfulness can enhance education research as well. By emphasizing choice, wonder, and delight, we help researchers imagine possibilities, experiment with materials and ideas, and maintain a positive and inquisitive stance in their work.

PPR is also connected to existing traditions in teacher research and participatory action research. PPR is based on the understanding that teacher-researchers can and should participate in producing and disseminating knowledge for the field (Cochran-Smith & Lytle 1999; 2009). In PPR, teachers collaborate with university-based researchers as active participants in both understanding and generating new ideas about teaching that can be shared with the field (Anderson & Herr 1999) and is similar to existing research (Souto-Manning & Mitchell 2010). Finally, PPR relates to traditions of participatory action research (Reason & Bradbury 2008; Noffke & Somekh 2009), because in PPR, research is conducted with rather than on teachers and classrooms.

PPR is a relatively new form of teacher research. To develop this approach within the Pedagogy of Play initiative, we interviewed more than 40 teacher-researchers at the International School of Billund, then analyzed and discussed their ideas in order to articulate what PPR is and how it works. We have found three defining characteristics of PPR:

- Engaging in playful activities and provocations to promote creative thinking

- Playing with our roles as teachers to test new ideas by using a playful mindset

- Collaborating with children as coresearchers in playful ways

First, since play involves envisioning the future and imagining possibilities, in our data collection and especially in our data coanalysis, we engage in playful activities and provocations. For example, the hide-and-seek activity that the study group engaged in is one example of a purposefully playful activity integrated into the data analysis process (one that we unpack later in this article). Another example is something we call documentation speed dating, in which teacher-researchers share raw data with each other quickly and playfully, using a graphic organizer called a bubble catcher to track questions and ideas that arise before they float away. We have experienced this as a source of playful learning, in part because “speed dating” evokes a playful mindset and “bubble catcher” is whimsical, but primarily because of the lively exchange of ideas that happens among us in the discussions about our research questions and documentation. These activities are not just for fun. They are informed by a guiding principle from the Pedagogy of Play: in playful learning, play activities should be purposeful and connected to our research goals. (See “Getting Started with Playful Participatory Research” below for ideas, as well as additional resources for educators from the Pedagogy of Play project.) Speed dating, for example, serves our goals of having a window into each other’s classrooms and research questions, and providing feedback to each other in a supportive environment.

A second distinguishing characteristic of PPR is that teacher-researchers test new ideas through playful learning. They “play with” their roles as teachers, using the classroom environment, materials, and curriculum to try out new approaches as they explore their research questions. This playful testing of ideas is essential to the research processes of PPR; the playful adult learning environment is intended to support the development of a playful learning environment for children. Just as children benefit from dramatic play to support their learning of concepts (e.g., pretending to open a restaurant offers children authentic opportunities to use emergent literacy skills as they create menus and signs), in PPR we’ve played around with the learning environment, sometimes setting up research meetings to feel more like a visit to a café or spa. The intention is to elicit a more relaxed state of mind and foster the kind of idea exchange educators might have with a good friend over a cup of coffee.

Finally, in PPR teachers aspire to engage children as co-researchers in their classrooms, asking for their feedback about playful learning experiences and approaches. For example, when Marina and Carolina, a kindergarten coteaching team, wondered, “What would happen if we had fewer rules on the playground?” they engaged the children as coresearchers in the process (Baker & Barbon 2017), talking with them about data collection, experimenting with fewer rules, and documenting the process and the results. The children demonstrated that they were very capable of being researchers. For example, one innovation they suggested was wearing special bracelets to make it clear to children from other classes that they were engaging in research so that their relative freedom did not seem unfair. They wore these bracelets when they were trying out having only two playground rules: take care of each other and take care of the materials on the playground.

Structuring playful participatory research

In our PPR work at the International School of Billund, these three defining characteristics are enacted through a research structure called study groups. These are inquiry communities in which teacher-researchers and university-based researchers come together on a monthly basis to explore a particular topic of interest. Individuals choose and pursue their own research questions that are relevant to their practice, but the group may sometimes come together around a shared topic. Study group sessions are coplanned by a teacher and a Project Zero researcher who meet regularly to discuss the learning goals for the group and ongoing inquiry topics, and to consider which playful research activities to engage in during the next study group meeting. At the end of each school year, study groups share what they have learned and the questions they intend to pursue through future inquiries during a celebration that includes all members of the school community—other teachers, administrators, children, and families.

The practice of pedagogical documentation is the data collection and analysis process that frames and drives these sessions, enabling educators to share and analyze inquiry questions and data together. By documentation we mean “the practice of observing, recording, interpreting and sharing, through a variety of media, the processes and products of learning, in order to deepen and extend learning” (Krechevsky et al. 2013, 74). In practical terms, this means that PPR researchers engage in an ongoing process of making video and audio recordings, writing notes, taking photographs, and gathering examples of children’s work for review. A digital platform (accessible only to members of the study group) enables easy posting and commenting on a range of media to facilitate sharing documentation with other group members and to track our inquiry questions and data over time.

Teacher-researchers engage in all aspects of the research process: choosing a research question, formulating a hypothesis, collecting data through the process of pedagogical documentation, reflecting on and analyzing that data with colleagues through the online platform and study group sessions, and sharing research findings with colleagues and the broader school community during the annual celebrations. To ensure that teachers’ research- and practice-based wisdom is shared with the field, publishing the results of (and reflections on) PPR is also encouraged. In the case study that follows, we illustrate the full PPR process as one teacher-researcher study group at the International School of Billund envisioned, designed, and created a makerspace for young children.

PPR in action: A makerspace comes alive

The International School of Billund is an International Baccalaureate school that focuses on play to increase children’s interest in learning. It serves over 300 children ages 3 to 16 in a small city in Denmark. At the time of this project, the whole school community had been involved in a school–university partnership within the Pedagogy of Play initiative for nearly three years, using PPR to deepen understandings about learning through play across age groups, learning domains, and content areas.

In 2017, we (Megina and Gaby), along with all of the early childhood teachers at the school, were part of the Kindergarten Playful Environments Study Group (one of five study groups at the school). For the first half of the year, we were each pursuing individual lines of inquiry, all related to considering how classroom environments can best support learning through play. Midway through the year, an idea took hold in the group, and it quickly became a shared inquiry focus: developing a makerspace for young children. Makerspaces—environments where individuals can come together to work with materials and technology in collaborative and open-ended ways—are growing in number and popularity in schools and public spaces such as museums and libraries (Deloitte Center for the Edge & Maker Media 2013).

The International School of Billund already had a Creator Space—a large makerspace at the heart of the school with a central common space and several adjacent breakout rooms. It was spacious and well equipped but, as Marina, one of the kindergarten teachers, explained, “It feels like a big kids’ room.” At the study group’s December meeting, we started talking about the idea of turning one of the small breakout rooms into a space just for the 3- to 6-year-old children. Excitement in the room was high, ideas started flying, and a shared inquiry was born.

The process: Envisioning and creating the Kindergarten Creator Space

Over the next few months, we focused on our shared questions: What could a Kindergarten Creator Space look like? How can we design this space together? We used study group sessions to envision and design the Creator Space, and also engaged the support of Amanda, a university-based researcher from Tufts University (who had been involved with the school’s makerspace). With Amanda, we engaged in PPR activities such as a card-sort to identify and discuss the kinds of experiences that study group members hoped children would have in the new Creator Space. Amanda also spoke with children, gathering their opinions about what the new space should include. The children said they would like to use the Creator Space to work with some novel materials and ideas like robotics and circuits, and they also expressed some interest in using clay and cardboard for construction.

The card-sort conversation—a moment of playful inquiry—generated a set of shared values for the development of the new space and led to more concrete shared planning about the materials, furnishings, and layout. Combining Amanda’s expertise of makerspace design with our input, we brought a plan to the school’s leadership, suggesting that we might repurpose one of the breakout rooms to realize our vision for a Kindergarten Creator Space.

Negotiations ensued with leadership and teachers who were occasionally using the space we selected; this process was messy and not always playful, but ultimately we were able to reach an agreement and gain permission to use the breakout room to design a makerspace specifically for young children. Although the budget was limited, the school’s caretaker was gracious with his time and helped to move and repurpose some existing furniture. In addition, we purchased a few new materials, including basic art supplies (paint, markers, scissors, glue) and loose parts (pipe cleaners). We also received many donations of recyclable and reusable materials (cardboard, fabric) from families. During the planning and preparation, teachers in the study group engaged their classes, inviting children to participate in choosing, organizing, and labeling materials for the space. The new Kindergarten Creator Space was up and running by late February. As a group, we experienced three elements of playful learning that are essential for children and adults—choice, wonder, and delight. We enjoyed choice in our process and research questions; felt wonder, or curiosity, as we considered how the children would respond to the new space; and experienced delight in our sense of success.

Enhancing the creator space

Eager to continue the inquiry, we agreed on a new shared research question: How do children explore the Kindergarten Creator Space? We hoped to learn what was working well in the space and with the materials, and what we might need to adjust to better support learning through play. Each class made an initial visit to the new Creator Space, and we documented the children’s experiences through videos, photographs, and transcripts of their conversations. We aimed to be transparent about our research question, letting the children know that we were trying something new as teachers and asking them if they wanted to contribute ideas to the research process. For example, Marina, the study group cofacilitator, recruited volunteers from her class to visit the Creator Space and asked if she could make a video of them exploring it and sharing their ideas.

As the children played with the materials in the Creator Space, they asked questions, explored the space, and generated new ideas for projects. The way they used the space and materials varied by age and interest. For example, one group of 5-year-olds decided to use found and recycled materials to build a sofa and a television for dramatic play, while a 3-year-old remained at the light table for 20 minutes, manipulating a variety of colored materials.

The teachers posted their documentation on the study group’s online platform, then viewed and commented on each other’s posts in preparation for the upcoming monthly meeting. For example, after viewing a video of the K2s (4-year-old class) exploring the space for the first time, one teacher commented in a reflection post, “I see some children asking teachers ‘What can we do?’ I think that, like the K1s [the 3-year-old class], the children are used to having adults prepare activities for them, so this process of choosing from scratch is new and a bit unfamiliar. . . . Is there a balance of child- and adult-led provocations/activities in this space that would be optimal? Or should it shift from day to day?” Questions like these provoked fresh ideas for facilitating learning in the Creator Space.

When we met again in April, we brought hard copies of our documentation for a playful hide-and-seek gallery walk in the Creator Space—the vignette at the beginning of this article. Our goals during this activity were to (1) look closely at documentation together to learn more about how children were experiencing the Creator Space, (2) engage in shared analysis, and (3) consider next steps for adapting the Creator Space environment to better support the children’s learning through play.

Ruth, one of the teacher-researchers in the study group, recalled, “It felt playful when we were . . . hiding [sticky notes] for people to find. . . . We were thinking about the space in a way that we wouldn’t if we just sat at the table and talked about it.” Indeed, through this playful engagement with each other’s documentation and with the space, we identified aspects that appeared to be supporting learning through play (the array of loose parts and the light table) and those that seemed to hinder it (possibly having too many materials and needing more display space for children to store their works in progress). During this discussion, we also expressed pride in having created the space together: it was constructed based on the relationships we have with the children we teach. We included them in selecting materials, laying out furniture, and writing our “Essential Agreements” about how the space would be used. The space felt unique because it represented these relationships (Malaguzzi 1994).

Reflecting on playful participatory research

Notice how the three defining characteristics of PPR were evident in this case study. First, as Ruth explained, the sticky note activity felt like a moment of playful learning and a way to generate new ideas and possibilities that might not have been explored by just sitting and talking. Next, we experimented with the environment of the makerspace, envisioning and creating something new to respond to a shared interest in supporting children’s learning through play. And finally, we invited the children into the research process, telling them about our research question and asking if they wanted to explore the new space and share their ideas about how it could be used. The children played in the space as they had these conversations, which seemed to elicit thoughtful contributions to the research process.

Describing the experience of being a playful participatory researcher, Gayle explained, “I feel like I’m on a team—it’s part of your day, part of your way. . . . I feel more active—an active learner.” Helena, the after-school program coordinator, mentioned that just talking with each other about research questions and documentation felt playful: “We see each others’ questions and the playfulness in each others’ questions . . . [and] help each other get new ideas.”

Some of the most playful aspects of our playful participatory research happened simply in the exchange of ideas among colleagues. This was a somewhat surprising and powerful realization for us. We hypothesized that the playful provocations and processes in the study group, like the hide-and-seek game and the documentation speed dating, would help us cultivate a playful mindset. Being in a relaxed and playful state of mind, we were eager to share ideas and feedback with each other; we experienced playful learning when the documentation we shared offered windows into each other’s classrooms, providing a common reference point for generative and supportive dialogue.

Of course, PPR can’t be playful all the time. Helena explained that PPR doesn’t feel playful “when it’s too school-school. When it feels like we’re forced to learn something. But I’m also aware that it can’t just be fun every time.” Helena was referring to some of the more technical aspects of our teacher research—like learning how to edit videos for pedagogical documentation or how to operate our private online data-sharing platform. We agree with Helena that there are moments of PPR that feel more like work than play (like when we are editing video clips to share with our colleagues and the technology isn’t on our side). Yet we find that the bigger picture of sharing this documentation with each other, and the playful and engaging conversations that result, keep us motivated to push through those less playful moments and take them in stride.

Taking playful learning seriously

When children or adults engage in a process of inquiry that is self-chosen, is personally motivating, and has meaningful implications, they can lose themselves in the inquiry process. Inquiry becomes play. It was in this spirit of inquiry as play that the teachers in the Kindergarten Playful Environments Study Group went about their journey, experiencing choice in the shared decision to pursue a research question of interest to them, wonder in observing the children as they explored the new space for the first time, and delight in the sense of community and satisfaction that came with the successful creation of the makerspace (which they continue to use with their early childhood classes).

In our work as teachers, researchers, and teacher-educators, we take teachers’ professional development and learning very seriously. This is why we aim to activate playfulness in the process of teacher research. Playfulness can lead to new ideas and productive risk-taking. As we continue to develop and document the playful participatory research approach, we hope that others will be inspired to try it out, play with new ways of engaging in teacher research, and share their experiences with others.

Getting Started with Playful Participatory Research

Want to give playful participatory research a try? Here are some suggestions for getting started.

- Form a study group: Members could be colleagues or teachers at your school or from different schools. If forming a group feels like a challenge, start by partnering with one professional colleague.

- Pick a research focus: You can have your own research question or you can share a question with colleagues. Pick something that you genuinely feel curious about and want to explore—that choice is part of what makes this research process playful!

- Document: Collect documentation from your classroom that is related to your research question. Include videos, audio recordings, photographs, written notes, and samples of children’s work. Start small—try to capture a few minutes of video or record the audio of one whole-group conversation. Review your documentation and pick a small piece (something that can be viewed in less than three minutes) to share with your study group.

- Play and discuss: Meet with your study group regularly to share and discuss your documentation and to engage in playful provocations related to your research questions. For example, if you are exploring the use of natural materials in your classroom, you might use some of your study group time for a workshop using natural materials and the rest of the time reflecting on video clips from the children in your classroom working with the same materials.

- Repeat: Continue to explore your research question as long as it feels relevant to you. As you go, use a journal, private online platform, or binder to track hypotheses, feedback, and reflections about your question.

- Share beyond the study group: When you feel ready to share some hypotheses and findings from your research, let your colleagues know! We organize an annual celebration of what we have learned in our study groups to share our research and findings with the entire school community.

For a set of tools that will guide you through each of these steps, visit the Pedagogy of Play toolbox, developed by educators at the International School of Billund: www.isbillund.com/en-gb/pedagogy-of-play/pop-toolbox.

References

Anderson, G.L., & K. Herr. 1999. “The New Paradigm Wars: Is There Room for Rigorous Practitioner Knowledge in Schools and Universities?” Educational Researcher 28 (5): 12–40.

Baker, M., & M.B. Barbon. 2017. “Too Many Rules on the Playground: Working the Paradox between Safety and Freedom.” Pictures of Practice. International School of Billund. www.isbillund.com/en-gb/pedagogy-of-play/papers-and-pictures-of-practice.

Baker, M., M. Krechevsky, K. Ertel, J. Ryan, D. Wilson, & B. Mardell. 2016. “Playful Participatory Research: An Emerging Methodology for Developing a Pedagogy of Play.” Working paper. Project Zero. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Education. www.pz.harvard.edu/resources/playful-participatory-research-an-emerging-....

Cochran-Smith, M. 2012. “A Tale of Two Teachers: Learning to Teach over Time.” Kappa Delta Pi Record 48 (3): 108–22.

Cochran-Smith, M., & S.L. Lytle. 1999. “Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Teacher Learning in Communities.” Review of Research in Education 24 (1): 249–305.

Cochran-Smith, M., & S.L. Lytle. 2009. Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

Deloitte Center for the Edge & Maker Media. 2013. Impact of the Maker Movement. makermedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/impact-of-the-maker-movement.pdf.

Escamilla, I.M., & D. Meier. 2018. “The Promise of Teacher Inquiry and Reflection: Early Childhood Teachers as Change Agents.” Studying Teacher Education 14 (1): 3–21.

Frost, J.L., S.C. Wortham, & R.S. Reifel. 2012. Play and Child Development. 4th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., R.M. Golinkoff, L.E. Berk, & D.G. Singer. 2009. A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Presenting the Evidence. New York: Oxford University Press.

International School of Billund. n.d. PoP Playbook. Pedagogy of Play project. www.isbillund.com/en-gb/pedagogy-of-play/pop-playbook.

Krechevsky, M., B. Mardell, M. Rivard, & D. Wilson. 2013. Visible Learners: Promoting Reggio-Inspired Approaches in All Schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Malaguzzi, L. 1994. “Your Image of the Child: Where Teaching Begins.” Trans. B. Rankin, L. Morrow, & L. Gandini. Exchange 3. www.reggioalliance.org/downloads/malaguzzi:ccie:1994.pdf.

Mraz, K., A. Porcelli, & C. Tyler. 2016. Purposeful Play: A Teacher’s Guide to Igniting Deep & Joyful Learning Across the Day. Porstmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Noffke, S.E., & B. Somekh, eds. 2009. The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. London: SAGE.

Perry, G., B. Henderson, & D.R. Meier, eds. 2012. Our Inquiry, Our Practice: Undertaking, Supporting, and Learning from Early Childhood Teacher Research(ers). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Reason, P., & H. Bradbury, eds. 2008. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

Souto-Manning, M., & C.H. Mitchell. 2010. “The Role of Action Research in Fostering Culturally-Responsive Practices in a Preschool Classroom.” Early Childhood Education Journal 37 (4): 269–77.

Authors’ Note: The authors would like to acknowledge the LEGO Foundation as a funder and intellectual partner of this work.

Photographs: courtesy of the authors

Megina Baker, PhD, is the new director of teaching and learning at Neighborhood Villages, a systems-change non-profit that supports child care centers in Boston, Massachusetts. Megina has been a lecturer of early childhood education at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development; she also is a collaborator on the Pedagogy of Play project at Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero. [email protected]

Gabriela Salas Davila is an early childhood educator and homeroom teacher at the International School of Billund. She has been actively involved in participatory research regarding Learning through Play with Harvard’s Project Zero. gabr1298@edu. isbillund.com