The Complexity of Preparing New Teachers

You are here

“Good grief! Young adults doing inquiry on snowmen? Really? You’re all 21 years old and you expect me to let you study snowmen?” These frustrations ran through my mind, but I didn’t speak. I listened. My class of future early childhood educators was bubbling with suggestions. I remained silent, marveling at how similar this moment was to one many years ago when my preschool students decided to use the pool noodles in the classroom as elephant trunks while making elephant sounds (Kampmann & Bowne 2011). This was a game changer. For this teacher preparation course, I had planned for the students to develop an inquiry based on observing the moon over 28 days, working from the teacher’s perspective while also participating in the investigation from the child’s perspective (Chancer & Rester-Zodrow 1997). But before I finished explaining my plan, one of the students blurted out, “How about a snowman journal?”

I knew this would change the course of my semester, my pre-planned lectures, and my compartmentalized assignments. Still, I found myself letting preservice teachers take the lead. In that instant, I said yes—and the rest, as they say, is history. Lectures would change, research would overwhelm me, rubrics would be rewritten and assignments redefined. In the end, it has been the single best achievement in my years of working with preservice teachers. Now, I do this as often as possible—but in that moment, I was both excited and scared.

The hair stood up on my arms. All kinds of ideas came rushing to my mind, so many I had to blurt them all out at once to the students. Then I did something I hadn’t done before. I stopped the class and asked them to notice the changes I was going through as a teacher, especially how I was struggling with letting go of what I had planned. I wanted them to see what it would be like once they were in the driver’s seat and the children in their classrooms gave them something to think about that might change the course of their curriculum. During the semester, I often asked them, “Do you remember what happened when it hit me that we were on to something?,” and they would inevitably say that I got goosebumps or got really excited, running around the room and babbling idea after idea. I felt it was critical for me to be explicit about my thoughts and actions from a teacher perspective so that they would be more aware and open when this happened in their own practice.

Inquiry learning

While there are numerous packaged instructional programs—complete with texts, lesson plans, and assessments—available to teachers (often mandated by school administrators or followed by teachers who feel pressure to meet state standards), it takes a leap of faith and some vulnerability to move toward inquiry learning. While teachers can, and should, enter their classrooms with a plan in hand, they should also be open to dialogue with the learners. Learners come to the classroom with backgrounds and family histories, varying levels of development, lives in communities, hopes, dreams, interests, and questions! All of these need to be respected, valued, and validated in a negotiation of what they want to learn, filtered through the lens of what the teacher needs them to accomplish. Each person’s collective body of culturally developed knowledge and skills—their fund of knowledge (Moll 2010)—represents critical information that teachers have a duty to collect in order to better serve their students. It is part and parcel of respecting the student as an individual and as a learner.

In the snowman inquiry, the students were using the Piagetian task of imitating the child in order to enter the flow of a child’s thought process, much like when a teacher engages in parallel play with a child to support the child’s investigation (Forman & Kuschner 1977). In our teacher education program, this process is used to enable student teachers as adults to understand the complexities of child-initiated, inquiry based learning.

Respecting learners

Asking good questions and setting up activities and environments that provoke good questions help teachers respect the gifts each learner brings to the classroom (Project Zero 2016). Meaningful discoveries happen when teachers intentionally create tasks that inspire curiosity by challenging children’s pre-existing knowledge and understanding. As teachers observe children’s behavior, they ask thought provoking questions to indirectly guide and deepen children’s exploration.

During the snowman study, the activities I planned for my teacher-preparation students mimicked activities that an early childhood educator would have planned for preschool students. A key part of this was purposefully embedding materials in the environment that would cause the students to stop and reconsider what they thought they already knew about the topic. For example, having mysterious mail appear from a snowman in Michigan sent them on a quest to see who the letter writer could have been. They knew snowmen didn’t know how to write letters, but how did the mail end up at the university classroom?

When the local newspaper picked up the story on the snowmen on campus, one student in the inquiry group

told the reporter, “I’ve loved every part of this assignment. . . . It’s the real deal” (qtd. in Schuster 2011).

This is the way to understand how children approach learning—not reading about it in a textbook,

but getting involved in planning, implementation, and executing the investigation.

Source: Schuster, “Snowmen Show Up for Class,” 2011.

While it is easy to theorize what might happen in the classroom, there is no better teacher than experience. This process of researching one’s own practices echoes the reflective practice education philosopher John Dewey proposed for teachers to work through issues in the classroom (Rice & McKeny 2012). The process I took with my students—stepping back and analyzing our curriculum through the child lens and the teacher lens—enabled me to engage in my own inquiry, which gave me a deeper understanding of my pedagogical practices.

Standards and data

Throughout the snowman investigation, I was careful to keep true to the student learning outcomes that were critical for the course:

- Create, select, and use informal assessment strategies to evaluate student progress; use assessment results to facilitate student achievement;

- Analyze and evaluate the unique nature of diverse early childhood settings;

- Associate key theorists with current practices;

- Demonstrate competence in planning developmentally appropriate curriculum; and

- Integrate learning experiences and activities using tools of inquiry in all curriculum content areas.

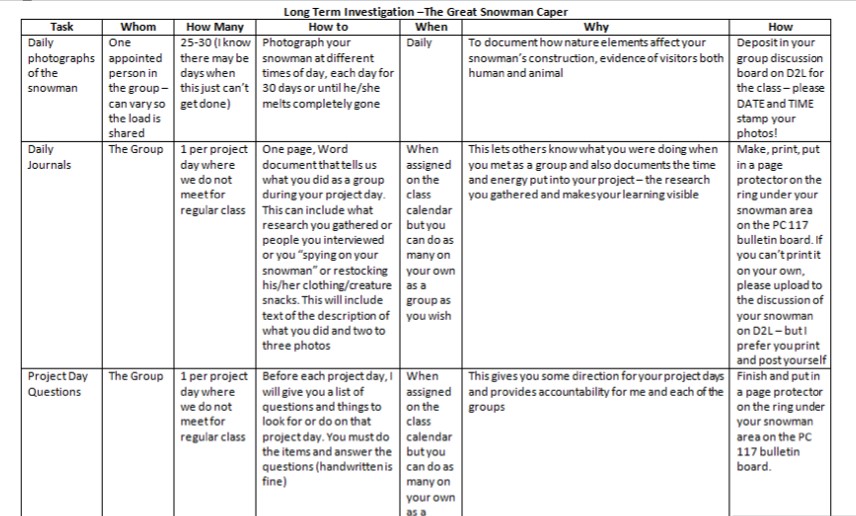

As I revamped assignments to reflect the students’ snowman project instead of my original moon project, I tried to engage in open, careful, and reflective planning to connect the activities and assignments back to the intent of the course. I was excited about following the students’ lead, but I needed to make sure essential content learning was not lost along the way (Sadaghiani & Costley 2009). I shared each change with the students in a detailed chart that included a rationale for each task they were performing.

Showing the students what I was questioning and struggling with seemed important for their development as future teachers. I wanted them to understand that one doesn’t simply plan an activity because it sounds fun or is part of a theme. Proper planning is mindful of the students’ development (whether those students are children or adults) and respectful of the learning that must occur.

Making learning visible to teachers

Just as we try to make learning visible to children, families, colleagues, and the community with documentation, it is important for teachers to record their instructional choices and the reasons for them as part of their planning process (Perkins 2002). If planning is just checking off boxes on a list of standards, then the “why” of learning activities might not be fully explored, leading to curriculum that isn’t meaningful to the learner.

Thoughtful and detailed documentation of children’s learning can be a work of art to be enjoyed by families, administrators, colleagues, and community members. The most powerful use of making learning visible is to bring documentation back to the learner for the purpose of extending reflections on learning. Documentation that enables teachers and learners to revisit the journey helps guide next steps (Wiggins & McTighe 2005; Turner & Wilson 2010). Traces of learning captured in photos, videos, work samples, and supporting contextual information can encourage a remembrance of events and identify avenues yet to explore among preschool children and teachers (Mantei & Kervin 2014).

Reflection

My own learning about how to teach about early childhood curriculum grew tenfold during this experience. I have never worked so hard to listen to my students and try to anticipate their next set of questions. I had to slow down, put my students’ desires before my own, and assess and plan daily in order to be sure I was honoring their questions. Using photos, short videos, and keywords that captured my recollections of what we undertook, my gift to the students was a video that used images and carefully chosen words to show them the learning we engaged in together. (To see the video, go to https://animoto.com/play/a21tQ0GfZ71lHP78OJe0uw.)

While a short video is hardly considered quality pedagogical documentation, it pulled together my emotional journey. If I could do the snowman project over, I would have spent more time on my documentation, including my reflection on the process from my teacher perspective. While I managed to verbalize all of my thinking with my students, I could have been better about keeping a journal or going back and putting together all of my notes, photos, and artifacts in a more careful and meaningful manner. As a person who is always moving from one thing to the next, I sometimes lose those big ideas—those aha! moments—in transition from task to task.

In the end, the most important lesson for me was to make time: time to listen, to reflect, to slow down, to be in the moment, and to let students teach me as much as I taught them. I still carry those ideals in my classes and in my relationships with all learners. It was important to me to approach this from a narrative inquiry perspective because I believe that in teacher education, and as classroom teachers, we need to be transparent about the processes we go through in the practice of teaching.

Because of the way this approach to inquiry teaching took off for me, I continue to teach in this manner to the extent I can. I make time to listen to what the students are telling me and adapt my practice to address both what I feel compelled to teach and what they want to learn. A colleague (who was with me at SDSU at the time of the snowman project) also implemented the same approach on her campus in the fall with scarecrows. I was heartened to hear that she successfully created the same learning experience for her curriculum class students.

References

Chancer, J., & G. Rester-Zodrow. 1997. Moon Journals: Writing, Art, and Inquiry through Focused Nature Study. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Forman, G. E., & D.S. Kuschner. 1977. The Child’s Construction of Knowledge: Piaget for Teaching Children, 1st ed. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Kampmann, J.A., & M.T. Bowne. 2011. “‘Teacher, There’s an Elephant in the Room!’: An Inquiry Approach to Preschoolers’ Early Language Learning.” Young Children 66 (5): 84–89.

Mantei, J., & L. Kervin. 2014. Interpreting the Images in a Picture Book: Students Make Connections to Themselves, Their Lives and Experiences.” English Teaching: Practice and Critique 13 (2): 76–92.

Moll, L.C. 2010. “Mobilizing Culture, Language, and Educational Practices: Fulfilling the Promises of Mendez and Brown.” Educational Researcher 39 (6): 451–60.

Perkins, D. 2002. King Arthur’s Round Table: How Collaborative Conversations Create Smart Organizations. New York: Wiley.

Project Zero. 2016. “Towards a Pedagogy of Play.” Working paper. http://www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Towards%20a%20Pedagogy%20o...

Rice, L., & T.S. McKeny. 2012. “Making Teacher Change Visible: Developing an Action Research Protocol for Elementary Mathematics Instruction.” Journal of Research in Education 22 (1): 266–90.

Sadaghiani, H.R., & S.N. Costley. 2009. “The Effect of an Inquiry-Based Early Field Experience on Pre-Service Teachers’ Content Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Teaching,” PERC (Physics Education Research Conference) Proceedings 2009, eds. M. Sabella, C. Henderson, & C. Singh, PER Conference series vol. 1179 (1): 253–56.

Schuster, V. (2011). “Snowmen Show Up for Class.” The Brookings Register, March 5, 2011, A1+.

Turner, T., & D.G. Wilson. 2010. “Reflections on Documentation: A Discussion with Thought Leaders from Reggio Emilia.” Theory into Practice 49 (1): 5-13.

Wiggins, G., & T. McTighe. 2005. Understanding by Design, 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: ASCD (Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development).

Jennifer A. Kampmann, EdD, is an assistant professor of early childhood education and assistant department head in teaching, learning and leadership at South Dakota State University.