Practice-Focused Inquiry. Introduction to “Leading Through Inquiry: Voices from a Community of Early Childhood Teacher Researchers” | Andrew Stremmel, Voices executive editor

Teacher research entails intentional and systematic inquiry by educators with the goals of gaining new insights into teaching and learning, becoming more reflective, effecting change in practice, and improving the lives of teachers and children. In this article, we have an excellent, yet all too rare, example of a group of coaches, teacher educators, and program directors engaging in practice-focused inquiry. They came from different types of settings and varied locations across one state, and together they created meaningful professional development opportunities grounded in their different and shared contexts.

Known as the Early Childhood Leaders Inquiry Group, these professionals sought to answer the question, “In what ways can a cross-context inquiry group support early childhood leaders in their work with early childhood educators?” Using digital tools, this inquiry group met monthly over one school year to engage in teacher research. This process encouraged everyone’s contributions. It evoked multiple perspectives, promoted active listening, and encouraged the sharing of discoveries about supporting teaching and learning through building trust, valuing experimentation and risk taking, and fostering a sense of lightness and joy.

The process described in this article reminds me of Carlina Rinaldi’s (2006) notion of professional development that derives from observation, reflection, exchange, comparison of ideas, and collegiality. Educators develop new understandings of practice by making their experiences visible and by contemplating, interpreting, and discussing documentation of their teaching and children’s learning. Because documentation always yields partial perspectives and subjective interpretations, it must be re-interpreted and discussed with other colleagues. Through debate and dialogue, “rigorous subjectivity” can occur as educators’ perspectives and interpretations are made explicit and contestable. Collectively, they can see, reflect on, and make sense of what is happening in the classroom.

Collaborative inquiry at its best is not only enlightening, educative, and empowering, it can be transformative, leading to changes in points of view. Here, we read about a group of early childhood professionals being methodical about how they see. They see differently, but through talking and listening, individual perspectives give way to socially constructed and shared understandings. As this group discovered, shared inquiry as a form of professional learning affords the space for addressing dilemmas of practice together and in meaningful ways. In the end, the authors demonstrate that inquiry groups are essential to doing teacher research. They serve as an avenue for professional development that reaches outward from the individual and provides reciprocal emotional and practical support. In their own words, “early childhood educators need each other.”

About the Author

Andrew Stremmel, PhD, is professor in early childhood education at South Dakota State University. His research is in teacher action research and Reggio Emilia-inspired, inquiry-based approaches to early childhood teacher education. He is an executive editor of Voices of Practitioners.

It is November, and the Early Childhood Leaders Inquiry Group—a group of coaches, teacher educators, and center directors from a variety of early childhood settings in the Northeast—is meeting for the second time this year. Today, Brenda Acero, the training coordinator at a diverse, urban network of family child care providers, is bringing her research questions and documentation to the group. She wants to know if it is realistic to ask new, home-based child care providers, many of whom are second-language learners, to create documentation for families. Armed with a newsletter created by one of her established providers, she asks her inquiry group peers for ideas.

“Brenda,” says Stephanie, “is there a particular family child care provider you could visit and document, then create a newsletter as a model?”

Megina adds, “Yes, modeling first, getting the process started. It could be part of Brenda’s role when she does these visits. She could take some pictures and write down what the children are saying. Then, she can hand her notes to the provider along with a newsletter template so they can continue the practice if they choose to.”

As the group continues to brainstorm ways Brenda can encourage documentation, she listens intently. Rather than having to come up with her own solutions, the inquiry group gives Brenda time to listen and feel supported. At the end of the meeting, she has a plan—she will visit her providers, observe and take pictures of children’s activities, then talk with her providers about what the pictures show. “I’ll make that the start of the process of creating a newsletter,” she says.

As teacher educators, we know that young children need high-quality early learning experiences to make gains throughout their education. We also know that high-quality early learning depends on highly qualified early childhood education professionals (Heckman et al. 2010; Zigler et al. 2011; Yoshikawa et al 2013; Friedman-Krauss et al. 2018). The nationwide Power to the Profession initiative and resulting Unifying Framework for the Early Childhood Education Profession (NAEYC 2020) are underway to unify and professionalize the early childhood education field. Still, our current system is fragmented, involving a patchwork of different program types and varying requirements for preparing and supporting teachers (Barnett & Belfield 2006; Friedman-Krauss et al. 2018, 190).

To begin to address this gap and to provide a framework for other educational leaders, a group of us in Massachusetts created the Early Childhood Leaders Inquiry Group. Meeting virtually, eight educators came together over the course of a year to investigate questions about practice and to support each other. Specifically, we sought to discover how a documentation-focused inquiry group could scaffold early childhood leaders in their work with early childhood educators. In this article, we describe how our inquiry group worked, what we learned, and how early education leaders can start and sustain a similar online inquiry group.

Grounded in Documentation

Educators can and should be producers—not just consumers—of knowledge for the education field (Cochran-Smith & Lytle 1999). Teacher inquiry groups offer a powerful model for professional learning that respects teachers as such. While professional learning communities (DuFour & Eaker 1998) have become popular in public schools, these tend to be data-driven and focused on student assessment. In contrast, an inquiry group is a community of teacher researchers that comes together to investigate questions about practice and to support each other (Mardell et al. 2009; Escamilla & Meier 2018). Inquiry groups ground their work in the process of gathering and interpreting documentation of children’s learning to drive teaching and learning (Project Zero & Reggio Children 2001; Cox Suárez 2006).

Although not widely implemented, the use of inquiry groups has been found to provide meaningful, ongoing professional development that fosters teacher efficacy and well-being along with an increased understanding of and ability to promote children’s learning (Mardell et al. 2009; Cochran-Smith 2012; Escamilla & Meier 2018). Typically, inquiry groups involve in-person interactions and engage educators within one school or across neighboring schools. However, the organizers of our group (Baker and Cox Suárez) sought to cast a wide net. In 2019 they invited early childhood coaches and program-level leaders from across Massachusetts to participate in a space where we could learn from and with each other across different contexts. These professionals represented community-based centers, Head Start, public pre-K, and family child care programs; the eight teacher researchers in our group included teacher educators, coaches, mentor teachers, and one student teacher.

Because we were so widely spread out and knew that in-person gatherings would be difficult to arrange, we decided to host monthly virtual meetings (eight in all) throughout the school year. We selected video conferencing (Zoom) coupled with a digital platform (Padlet) for sharing documentation and resources. Although unanticipated, this decision meant we could smoothly continue our work when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Documentation, or “the practice of observing, recording, interpreting, and sharing the processes and products of learning,” is essential for inquiry group work (Project Zero & Reggio Children 2001; Krechevsky et al. 2013, 74). Examples of documentation include transcribed words, images, and audio and video recordings of learning experiences. Revisiting and interpreting this documentation can reveal knowledge or skills attained and also learners’ social and emotional responses while engaging with each other, a critical aspect in group learning (Rinaldi 2006).

We followed an iterative teacher research process during our meetings that involved gathering data (documentation), interpreting that documentation independently and with colleagues, gathering new documentation, and eventually distilling themes that responded to the questions posed (Hubbard & Power 2003; Perry, Henderson, & Meier 2012). Initially, we used the See-Think-Wonder thinking routine (Project Zero 2019) as a way to look carefully at each other’s documentation by using a series of simple yet powerful reflective questions. This alleviated some members’ worries that their documentation might not be “good enough” to share with colleagues. As our meetings progressed and we grew more comfortable with each other, we found that many different forms of documentation prompted excellent discussion. Even small pieces (two quotes from teachers or a two-minute unedited video) prompted meaningful and lengthy discussions. (See “Group Protocol” below.) We used notes, recordings, and screenshots to document each of our meetings, which lasted from one to two hours. Between meetings, group members gathered new documentation, discussed their work with the teachers in their programs, and at times, electronically shared their data. This helped keep members informed and ready to participate in our inquiry group gatherings.

Data Sources, Analyses, and Themes

As stated earlier, our research question together was: In what ways can a documentation-focused inquiry group support early childhood leaders in their work with early childhood educators? After a year of meeting virtually, we began to review our data to answer this question. Specifically, we looked at

- transcripts and audio recordings from our monthly meetings (eight transcripts in total)

- documentation of classroom activities, conversations with teachers, and coaching sessions that we had gathered and shared on our virtual collaborative platform (in our case, a Padlet)

- classroom artifacts, including planning tools, photos, and children’s work

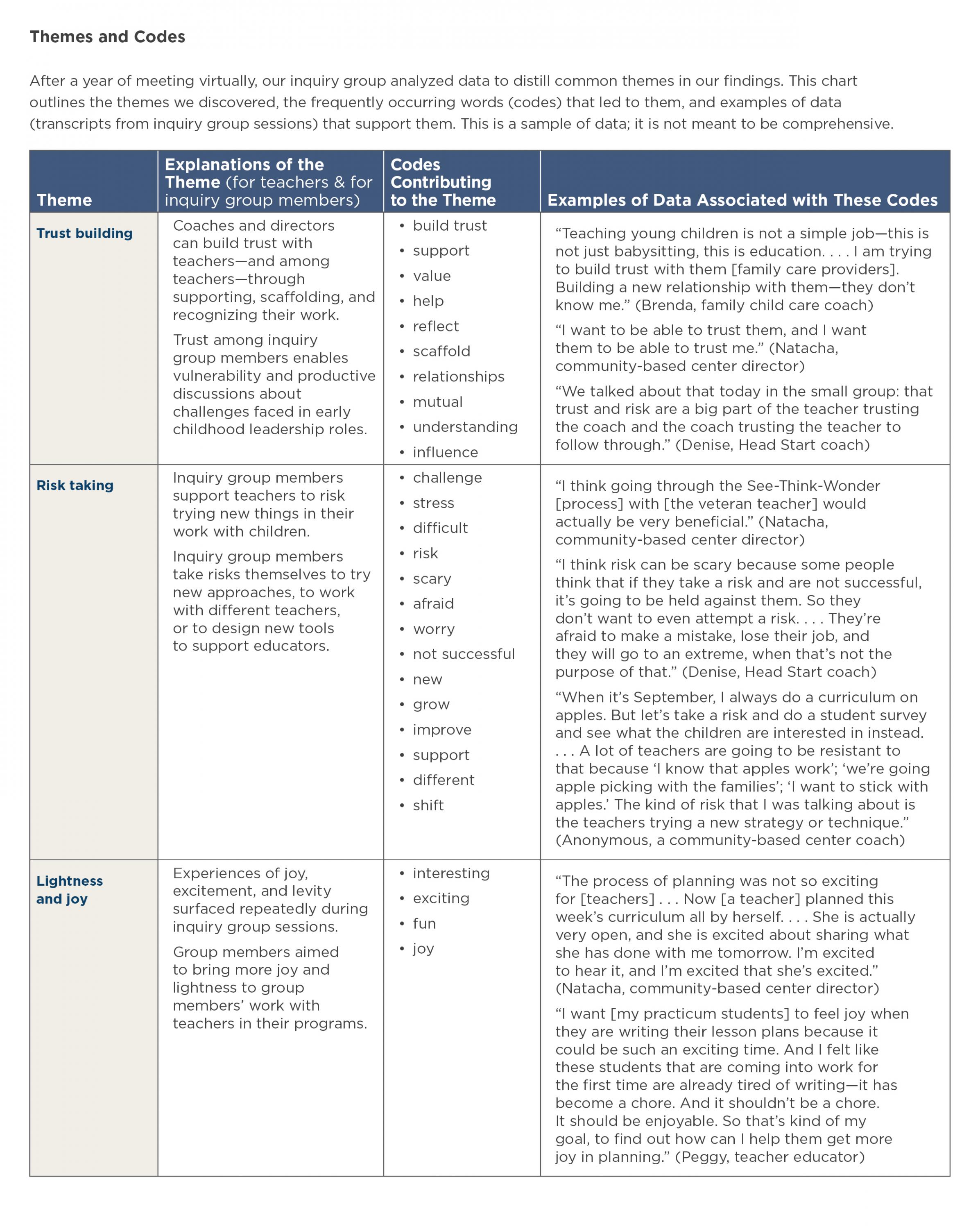

In addition, group members independently revisited their documentation, writing reflective memos and engaging in reflective conversations. We also focused several co-analysis sessions on the transcripts from our monthly meetings, using Braun & Clarke’s analysis approach (2006) to code them for overarching themes. (See “Themes and Codes” below.) Three framed our findings:

- Building trust: Participating in the inquiry group led to a deep and gradual experience of building trust as a community and supported trust-building with teachers.

- Valuing experimentation and risk taking: The inquiry group provided a space for valuing experimentation and risk taking.

- Lightness and joy: We regularly made space for lightness and joy, both during our time together and in our work with teachers.

An in-depth discussion of each follows.

Building Trust

How can I help a teacher ask children questions that will elicit deeper thinking and more words in their responses?

Denise is an education coach in an urban Head Start program. One of her teachers, Suchira, has a professional goal of asking more open-ended questions and giving better feedback to her students. Because English is not her first language, Suchira has asked for support with this aspect of her teaching.

With Suchira’s permission, Denise brings our inquiry group some video observations of Suchira. One of the clips captures conversations Suchira and her children have about a city design project, which was inspired by pictures of Chicago. During a group meeting, they discuss a pool that the children built from a plastic bowl. It has broken.

With Suchira’s permission, Denise brings our inquiry group some video observations of Suchira. One of the clips captures conversations Suchira and her children have about a city design project, which was inspired by pictures of Chicago. During a group meeting, they discuss a pool that the children built from a plastic bowl. It has broken.

“How can we fix the pool?” Suchira asks each child. She receives brief answers (paint it, use glue, put a top on it, put lights on it), but she does not ask follow-up questions to encourage problem solving or language development.

“As a coach, my goal with Suchira is to help her get fuller engagement with the children, to get longer responses in order to understand the children’s thought processes, and develop their language skills,” Denise says.

The inquiry group listens to Denise’s description, views the video clip, and discusses possible strategies for her next coaching session. These include modeling open-ended questions, offering “question starters” to post around the classroom, posing follow-up questions, and having smaller groups and more “wait time” for children to respond.

When the inquiry group meets again, Denise brings another video of Suchira, now leading a smaller group and implementing some of the recommended suggestions. “Suchira asked five solid, open-ended questions that led to authentic responses and a greater degree of engagement in conversation,” Denise says. “Suchira trusted me enough to share her videos and dilemma with the inquiry group and welcomed suggestions from this extended group of coaches.”

“Having the inquiry group view and discuss Suchira’s video helped me as a coach because it provided another set of ‘professional eyes’ observing and listening,” she adds. “The recommendations that were passed along to Suchira were directly responsible for her growth in questioning.”

In this example, trust is front and center: Suchira trusted Denise enough to share her videos and dilemma with the inquiry group, and she welcomed suggestions from this extended group of coaches. This allowed for transparent co-inquiry and opportunities for real growth guided by documentation.

Besides increasing trust in the classroom, we also noticed increasing levels of trust among our inquiry group members as time passed. Peggy, an experienced teacher educator who had participated in inquiry groups before, told us that she wanted to encourage her student teachers to plan for open-ended, inquiry-driven experiences. She shared photos, videos, and curriculum planning guides related to her student teachers’ lessons about wind tunnels.

Preparing and discussing her documentation with the group led Peggy to step back and consider the student teachers’ perspectives compared with her vision and goals for their planning and teaching. She noticed that while the student teachers expressed unease or uncertainty about their planning and teaching skills, some of their actions and reactions had the quality of “messing about” with a new material. With the inquiry group’s help, Peggy wondered if new teacher development and learning could include a phase akin to the “messing about” phase children have when they encounter new materials or experiences. How could she support her student teachers through this phase and toward greater skill, knowledge, and confidence?

Grounded by documentation, we began finding connections among our experiences. “I often ask the teachers, where does this idea come from?” Denise shared. “I always ask them to be on the lookout and to be following the children’s ideas.” Exchanges like this helped us form relationships and begin to build trust as a community of teacher researchers.

Features of Our Inquiry Group

- Monthly meetings during the school year, 1.5 hours long

- Open invitation to all educational early childhood education leaders

- Online format (Zoom) to allow members to join from across the region

- Digital platform (Padlet) to share documents, links, and video

- Meeting agendas that included a structured protocol to review each other’s documentation

- Discussion focus on current questions posed by leaders via the documentation they chose to share

- Meeting notes (text and/or audio) posted on the Padlet after each meeting

- Members welcomed to join anytime they were available

Valuing Experimentation and Risk Taking

What can I do to help my staff become as excited as I was about the planning process?

Natacha, the director of a new urban child care center that serves infants to preschoolers, knows that her teachers care deeply about the children although they are new to the Reggio-inspired teaching approach that she is working to cultivate. Teachers want to provide authentic and innovative learning experiences, yet Natacha notices a lack of enthusiasm during curriculum planning meetings.

Natasha brings a variety of documentation to our inquiry group. These include curriculum plans, weekly planning forms, and photos of children engaged in learning. After reviewing them, group members ask if the plans are too cumbersome. Are all the tools effective? Reflecting on the conversation and questions, Natacha realizes that she is too focused on fixing the “problem.”

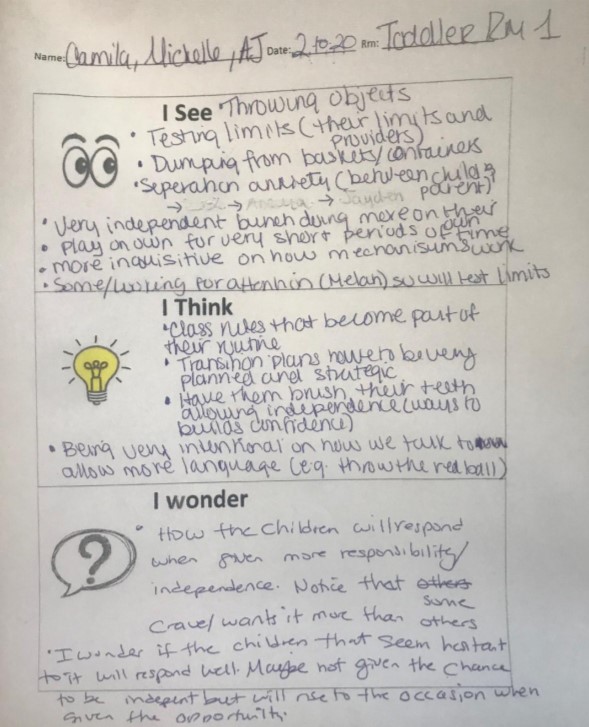

“I had success using the See-Think-Wonder protocol as a reflective observational tool for teachers to use and thought it would be a great start by reflecting on what they observe in the children, think about what they are seeing, and what they wonder about it,” she says. (See a sample below.) Although teachers agreed it was a good tool, the practicality was challenging—especially for toddler teachers who had little time to stop and write notes.

“I knew the teachers had their own ideas on how to make planning work, but how to get them to share those ideas was the dilemma,” she says. “I started to think about my own teaching experiences with children and techniques I used to scaffold them through their thinking, and that’s when I had my ‘aha’ moment. Why didn’t I just approach this the way I would have when teaching children?”

Natacha begins asking her teaching teams open-ended, scaffolding questions to encourage new ideas and to identify what is and is not working. Her teachers are then able to tweak those ideas to try again. Excitement increases, and so does the flow of ideas during her next staff meeting. A sense of teamwork emerges, and the teachers are enthusiastic about putting new plans into motion. That spark stays with the teaching teams well past the staff meeting.

Thanks to her discussions with the inquiry group, Natacha took a risk and pivoted in her work with teachers. As she adjusted to working alongside them, she also noticed a shift in the ways they related to each other.

Over the year, lesson planning became a common theme during our inquiry group meetings. Jenny, a graduate student participating in an inquiry group for the first time, acknowledged the difference between her work as a preschool teacher and the lesson plan template she now had to write in graduate school. She wondered how to lessen the burden of writing and to stop viewing lesson planning as “my homework as a teacher.”

This prompted a larger discussion. Over the next three meetings, group members brought different planning tools into our collaborative space:

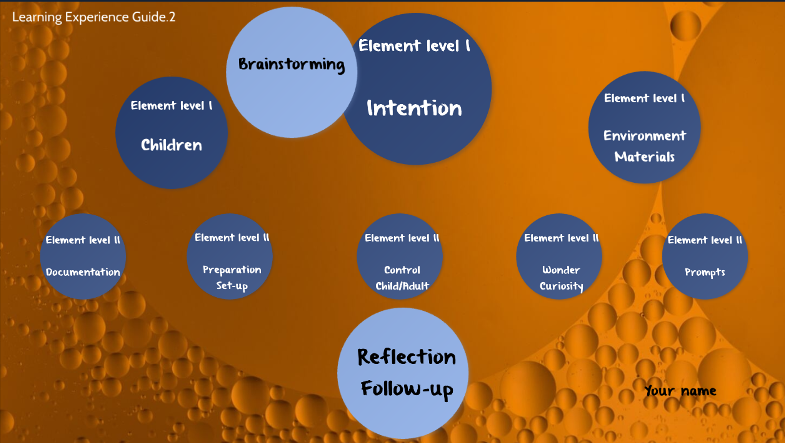

- Peggy presented the draft of a non-linear planning tool. Using an interactive visual program (in her case, Prezi), she created a circular planning format that can include photos, audio, video, and text. (See the example below.)

- Natacha shared the See-Think-Wonder planning tool she introduced to her teachers.

- Jenny shared the lesson planning template used for early childhood educators at her university, which she described as a “burden.”

Each of these actions spoke to the trust our inquiry group had developed and the way we encouraged risk taking. Jenny took a risk by sharing her frustrations with the university lesson planning template she was asked to use in her courses; Peggy and Natacha were driven by a desire to change their programs’ curriculum planning processes—Peggy because she was not seeing the kind of engaging, child-centered curriculum planning she hoped her preservice teachers would try out in their practicum placements, and Natacha because her teachers felt “really down and sad.” This sharing, in turn, inspired our other members: Natacha’s documentation of the See-Think-Wonder process as a tool for intentional curriculum planning inspired both Annalisa and Megina to simplify their planning tools.

See-Think-Wonder Planning Tool

Non-Linear Planning Tool

Lightness and Joy

How can we ensure that our planning tools reflect the values of our school?

Annalisa is a lead teacher at a university-based child care center that is expanding and reconsidering its monthly themed curriculum. After being asked to serve as a curriculum coach, she begins leading team meetings with a group of teachers at her center. At one meeting, as the team brainstormed ideas for the components of a planning tool, “we kept coming back to a sense of fluidity, to the necessary flexibility in the planning tools,” she says. “We touched on flexibility in following children’s interests and the importance of including opportunities for reflection. Ultimately, we compiled a list of potential components for a future planning tool.”

Annalisa brings her written notes from this team meeting as documentation to the inquiry group session. Using its reflective protocol, the group makes connections between Annalisa’s experience and the other discussions they have been having about planning tools. Group members comment that centering joy, building on children’s interests, and using documentation to drive next steps in curriculum are evident in Annalisa’s conversation with her colleagues.

What began as an inquiry group conversation about how to support and motivate teachers who were not excited about planning lessons has evolved into a larger, sustained dialogue about making space for lightness, joy, and excitement while intentionally planning learning experiences for young children. As Annalisa reflects, “Hearing about Natacha’s experience of success with See-Think-Wonder makes me inspired and optimistic about our own use of a similarly flexible planning tool.”

When we revisited transcripts of our discussions about group members’ questions and dilemmas, we noted that the words joy, lightness, and intentionality were common threads. Each member brought different perspectives and particular contexts to our inquiry meetings, and each was influenced by what they learned from others. This synergy would not have taken place without the inquiry group, and the questions and documentation we each brought to it became a fertile ground for discussing ideas and generating possibilities. The synergy was emergent rather than forced, showcasing the power of research questions that are generated by, rather than imposed upon, an education community (Bang et al. 2016). An inquiry group structure afforded a space for meaningful dilemmas of professional practice to unfold and be addressed collaboratively.

Documentation does not need to be polished or edited to spark a deep and powerful conversation.

As we know, teacher research and inquiry processes are not linear or easily contained (Bentley & Souto-Manning 2016); indeed, in a community of researchers like ours, the work does not need to be finished on a specific timetable or with a predetermined outcome. Rather, part of the lightness and joy that we found was in the experience of shared ownership of this inquiry space and the understanding that it can stretch and evolve to fit our needs over time.

Group Protocol

We adapted a protocol from Krechevsky et al. (2013) and kept this structure during each session.

- Presenter provides context and the questions for today. (3 minutes)

- Group looks at documentation. (3 minutes)

- Group asks simple clarifying questions. (2–3 minutes)

- Group discusses (presenter is silent): What do you see/hear in the documentation? Point to what makes you say that. (5 minutes)

- Group looks at documentation again. (3 minutes)

- Group discusses (presenter is silent): How do we respond to the presenter’s questions in relation to this documentation? What other questions arise? What are the implications for coaching and supporting teachers and the next steps for the presenter? (10 minutes)

- Presenter shares take-aways. (3 minutes)

Applying the Lessons We Learned

As we continue our inquiry work into the new school year, we hope to delve more deeply into planning tools by cocreating new tools and sharing documentation of our experiences using them. Early childhood educators need each other, and engaging in teacher research is one way we can elevate the voices of educators and deepen professionalism in our field (Baker 2020).

Based on our work this year, we feel confident that others can realize similar benefits by starting or sustaining an inquiry group.

Among our recommendations for ensuring success:

- Keep participants’ daily dilemmas at the core of the inquiry group’s work. Teacher research is most meaningful when it is driven by pressing and authentic questions from group members. For example, we resisted the urge to choose a shared inquiry question, and we were rewarded with a more organic, shared, and ongoing dialogue about redesigning our planning processes.

- Meet online. Even before physical distancing became a reality, our group found many advantages to meeting via video conferencing, paired with an online platform to share documentation. Meeting virtually was more flexible for everyone’s schedules and locations.

- Welcome participation when possible and accept flexibility. Encourage everyone to participate as much as they are able. Offer different ways to participate, such as posting transcribed notes from group sessions and offering ways to share feedback on colleagues’ documentation via an online platform. Understand when members cannot attend.

- Set norms on how to listen and work with each other. We did this at our first meeting and revisited it regularly to add to or change our norms as needed. Our norms included using a protocol to guide discussions, maintaining confidentiality, and beginning and ending on time.

- Keep the documentation raw and real. Documentation does not need to be polished or edited to spark a deep and powerful conversation. A few sentences of dialogue, some meeting notes, or a few photographs surprised us by always inspiring thoughtful conversation.

- Use the same protocol and structure for group sessions over time. The consistency will keep the focus on documentation and group members’ questions. (See “Group Protocol” above. )

If anyone out there is doing teacher research alone and wants a partner, or if you’ve never tried teacher research but want to give it a try, we’d love to hear from you to share ideas and to connect. We are stronger together.

Voices of Practitioners: Teacher Research in Early Childhood Education is NAEYC’s online journal devoted to teacher research. Visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/vop to

- Peruse an archive of Voices articles

- Read the Fall 2020 Voices compilation

Photographs: Courtesy of the authors.

Copyright © 2021 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.

Inquiry Group Participants

- Brenda Acero, former training coordinator for Acre Family Childcare

- Megina Baker, lecturer of early childhood education at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development, and a collaborator on the Pedagogy of Play project at Harvard University Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero.

- Peggy Martalock, associate professor of early childhood education, Greenfield Community College.

- Jenny Park, student teacher in early childhood; attending Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development.

- Annalisa Ritchie, lead teacher at Boston University Children’s Center.

- Natacha Shillingford, director of Epiphany Early Learning Center, serving infants to preschoolers.

- Stephanie Cox Suárez, clinical associate professor of special education at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development and founding director of the Documentation Studio, which offers educator support to document learning.

- Denise Nelson, education coach for 15 preschool classrooms at the Worcester Child Development Head Start Program, and a professor of education at Worcester State University.

References

Baker, M. 2020. “Promoting Equity Through Teacher Research.” Young Children–Voices of Practitioners 75 (2): 58–64. naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/may2020/promoting-equity-through-teacher-research

Bang, M., L. Faber, J. Gurneau, A. Marin, & C. Soto. 2016. “Community-Based Design Research: Learning Across Generations and Strategic Transformations of Institutional Relations Toward Axiological Innovations.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 23 (1): 28–41.

Barnett, S., & C.R. Belfield. 2006. “Early Childhood Development and Social Mobility.” Future of Children 16 (2): 73–98.

Bentley, D.F., & M. Souto-Manning. 2016. “Toward Inclusive Understandings of Marriage in an Early Childhood Classroom: Negotiating (Un)readiness, Community, and Vulnerability Through a Critical Reading of King and King.” Early Years 36 (2): 195–206.

Braun, V., & V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

Cochran-Smith, M. 2012. “A Tale of Two Teachers: Learning to Teach Over Time.” Kappa Delta Pi Record 48 (3): 108–122.

Cochran-Smith, M., & S.L. Lytle. 1999. ”Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Teacher learning in Communities.” Review of Research in Education 24 (1): 249–305.

Cox Suárez, S. 2006. “Making Learning Visible Through Documentation: Creating a Culture of Inquiry Among Pre-Service Teachers.” The New Educator 2 (1): 33–55.

DuFour, R., & R.E. Eaker. 1998. Professional Learning Communities at Work: Best Practices for Enhancing Student Achievement. Bloomington, Indiana: National Education Service; Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD.

Escamilla, I. M., & D. Meier. 2018. “The Promise of Teacher Inquiry and Reflection: Early Childhood Teachers as Change Agents.” Studying Teacher Education 14 (1): 3–21.

Friedman-Krauss, A.H., W.S. Barnett, K.A. Garver, K.S. Hodges, G.G. Weisenfeld, & N. DiCrecchio. 2018. The State of Preschool 2018. National Institute for Early Education Research. https://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/YB2018_Full-ReportR3wAppendices.pdf

Heckman, J.J., S.H. Moon, R. Pinto, P.A. Savelyev, & A. Yavitz. 2010. “The Rate of Return to the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (1–2): 114–128.

Hubbard, R.S., & B.M. Power. 2003. The Art of Classroom Inquiry: A Handbook for Teacher-Researchers (rev. ed). Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann.

Krechevsky, M., B. Mardell, M. Rivard, & D.G. Wilson. 2013. Visible Learners: Promoting Reggio-Inspired Approaches in all Schools. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

Mardell, B., D. LeeKeenan, H. Given, D. Robinson, B. Merino, & Y. Liu-Constant. 2009. “Zooms: Promoting School-Wide Inquiry and Improving Practice.” Voices of Practitioners 4 (1): 1–15.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). n.d. “Power to the Profession.” Accessed January 31, 2019. https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/initiatives/profession.

NAEYC (National Association for the Education of Young Children). 2020. Unifying Framework for the Early Childhood Education Profession. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Perry, G., B. Henderson, & D.R. Meier, eds. 2012. Our Inquiry, Our Practice: Undertaking, Supporting, and Learning from Early Childhood Teacher Research(ers). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Project Zero. n.d. See, Think, Wonder | Project Zero. Accessed July 2, 2020. https://pz.harvard.edu/resources/see-think-wonder.

Project Zero, & Reggio Children. 2001. Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners. Project Zero and Reggio Children.

Rinaldi, C. 2006. In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning. London: Routledge.

Yoshikawa, H., C. Weiland, J. Brooks-Gunn, M. Burchinal, L. Espinosa, W. Gormley, J. Ludwig, K. Magnuson, D. Phillips, & M. Zaslow. 2013. Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base on Preschool Education. Society for Research in Child Development, Foundation for Child Development. https://www.fcd-us.org/the-evidence-base-on-preschool/

Zigler, E., W. Gilliam, & S. Barnett, eds. 2011. The Pre-K Debates: Current Controversies and Issues. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Megina Baker, PhD, is the new director of teaching and learning at Neighborhood Villages, a systems-change non-profit that supports child care centers in Boston, Massachusetts. Megina has been a lecturer of early childhood education at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development; she also is a collaborator on the Pedagogy of Play project at Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero. [email protected]

Stephanie Cox Suárez, PhD, is clinical associate professor, special education, at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. Stephanie is the founding director of The Documentation Studio, which offers educator support to document learning. [email protected]

Brenda Acero, BA, is training coordinator at Acre Family Child Care in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Peggy Martalock, PhD, is associate professor of early childhood education at Greenfield Community College in Greenfield, Massachusetts. Peggy has extensive experience studying the Reggio Emilia approach. She is currently exploring this approach in the context of higher education. [email protected]

Denise Nelson, MEd, is an education coach at the Worcester Child Development Head Start Program and a professor of education at Worcester State University. Denise has been a member of the inquiry group for two years. [email protected]

Jenny Hanseul Park, BS, is currently a Boston University graduate student in early childhood education and working as a research assistant in Boston, Massachusetts. She was an intake worker at the PEACE Inc. Head Start Program in New York and taught preschool at Bright Horizons in Boston. [email protected]

Annalisa Hawkinson Ritchie, MEd, is a lead teacher at the Boston University Children’s Center, where she has been since graduating with her master’s degree in early childhood education from Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. She has worked with preschoolers in a variety of settings and looks forward to becoming a mentor teacher and pedagogista.

Natacha Shillingford, BS, is the director of an early learning center in Dorchester, Massachusetts, and has been in the field for a little over 20 years. She says she received most of her training from the many children she has collaborated with over the years and continues to learn with and from.