Five Tips for Engaging Multilingual Children in Conversation

You are here

Having conversations with children who are learning English in addition to their home languages—referred to in this article as multilingual children—is an essential skill for early childhood educators. Such engagement has implications for multilingual children’s developing identities as valued and knowledgeable members of their communities as well as for their language learning. Discussions between educators and children have been shown to facilitate language learning by providing children with models for use of language and responsive communication and by offering teachers frequent opportunities to check for comprehension (e.g., Mashburn et al. 2008; Ruston & Schwanenflugel 2010; Chapman de Sousa 2017). Conversations also contextualize topics, making topics relevant to multilingual children and potentially motivating them to practice using their new language just beyond their independent level—a practice that facilitates language development (Swain 2005).

Instructional conversations, which are small group discussions among children and teachers that focus on a learning goal (Tharp & Entz 2003), promote the language development of multilingual children (Institute of Educational Sciences 2006; Portes et al. 2017). Yet, to be effective, these conversations must engage multilingual children as active participants. Unfortunately, research indicates that in preschool classrooms serving culturally and linguistically diverse learners, interactions between educators and children are often in the form of giving and receiving directions, with limited opportunities for children to practice producing multiword sentences (Justice et al. 2008). Multilingual students who attended public schools in the United States have reported feeling “tongue-tied” and “silenced” (Santa Ana 2004). Early childhood educators can address these concerns by using pedagogy that facilitates and values all children’s contributions and voices.

As an instructional coach, I have often been asked for tips on encouraging multilingual children to join classroom conversations. In this article, I offer five strategies that take into account the unique aspects of learning an additional language and capitalize on the social and interactive nature of early childhood classrooms: use children’s home languages as a resource; pair conversations with joint activities; coparticipate in activities; use small groups; and respond to children’s contributions.

The research behind these tips is grounded in the work of the Center for Research on Education, Diversity, and Excellence (CREDE). Instructional conversations are a central aspect of the CREDE pedagogy, which has been shown to promote diverse learners’ academic achievement (Tharp 1982; Hilberg, Tharp, & DeGeest 2000; Doherty et al. 2003; Portes et al. 2017). This model emphasizes building relationships, and it supports teachers in helping children develop their complex thinking (Yamauchi et al. 2012) as well as their language and literacy skills (Saunders & Goldenberg 2007; Chapman de Sousa 2017).

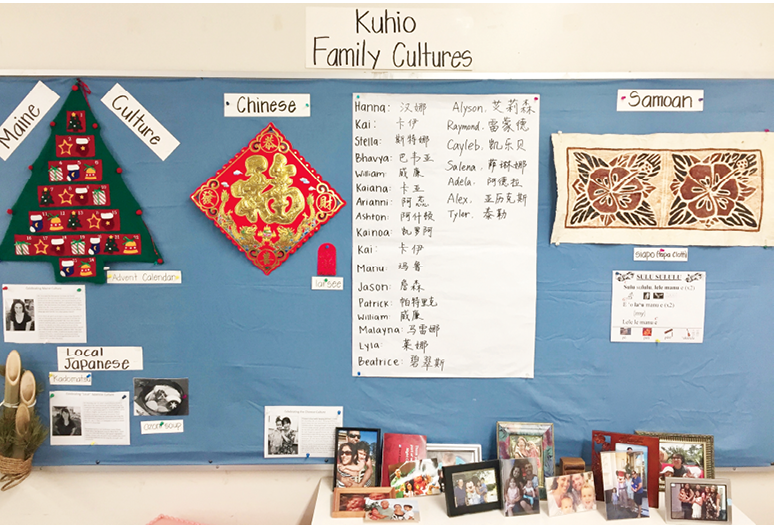

The CREDE Hawaiʻi project partnered with the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Children’s Center, a culturally and linguistically diverse preschool on O’ahu. Administrators and teachers at the center helped refine the CREDE model for teaching in early childhood (for a full description, see Yamauchi, Im, & Schonleber 2012). The center serves an international community whose members speak over 30 distinct languages. While the primary language of instruction is English, the educators encourage inclusion of Hawaiian and the children’s various home languages. The following engagement ideas include examples from observing and interviewing educators who have developed expertise in engaging diverse and multilingual children.

1. Use children’s home languages as a resource

Even if you do not speak the home languages of children in your program, you can still include their languages in conversations. Get help from family members by inviting them to come teach you and the class important words; also ask them for recommendations on literature and songs written and recorded in their languages. Additionally, remember that it is always possible to respond to children’s communications, regardless of whether or not you speak the same language. You can do so with body language and other ways to communicate, such as using pictures and objects. Responding to children’s multilingual contributions sends the message that diversity is valued in your classroom. It shows multilingual children that they have important ideas and questions to contribute, and that all forms of communication are of value.

Responding to children’s multilingual contributions sends the message that diversity is valued in your classroom.

To emphasize how deeply connected multilingual children’s forms of communication are, scholars have introduced the idea of translanguaging—using children’s full language abilities to encourage learning (García & Wei 2014). This is a conscious effort to alter the widespread concept of multilingualism as fluency in separate languages and instead emphasize that multilingual people have “one linguistic repertoire” (García & Wei 2014, 2). For early childhood educators, this concept may help reinforce the importance of encouraging children to communicate using their complete linguistic repertoires, including multimodal communication such as gesturing and drawing.

If you or other educators at your center speak additional languages, use those as another resource for creating a classroom ecology that celebrates diverse contributions. During my classroom observations in the center, I saw several examples of teachers capitalizing on their own and children’s multilingualism during instructional conversations. The children consistently responded with increased engagement.

During one observation, Kisho, a 4-year-old boy who had recently moved with his family from Japan to Hawaiʻi, was painting using mashed-up berries with his teacher, Ms. Rheta, and 4-year-old Cody. Speaking Japanese, Kisho asked things like, “What is in here?,” while pointing at the berry dye, and “Can you eat it?” Ms. Rheta, who understood Japanese, answered his questions in English and Japanese while also gesturing, pointing, and showing pictures on her camera. Later, Cody said, “Don’t eat” and repeated the Japanese word for “can’t eat” that Kisho had used.

This example shows how inclusive practices can benefit multilingual children and their peers: multilingual children have expanded opportunities to engage in learning, and peers discover there are numerous ways of describing the world. As was the case with Cody, peers are often are excited to hear and learn new words. The translanguaging during their conversation created opportunities for conceptual and linguistic development for both children—but they were particularly important for Kisho. Kisho could ask questions in his home language and engage with the nature and art concepts long before he became proficient in English. His engagement increased, and he heard new vocabulary being used in a meaningful way. Ms. Kristi, another educator at the center, said that translanguaging “helps children be part of the group, and it helps them feel knowledgeable . . . so they can share a piece of themselves and the others can learn from them. It brings up their esteem.”

2. Pair conversations with joint activities

There are several reasons why joint activities in small groups promote conversation: a shared activity gives participants a common subject to talk about; the tools or props related to the activity can aid in communication; and educators can tailor the activity and, based on the interests of the children participating, guide the conversation, thereby increasing the children’s motivation and the likelihood that they will share their ideas. Such learning, paired with activities, is a central component of the CREDE framework for instruction (Tharp & Entz 2003; Yamauchi, Im, & Schonleber 2012).

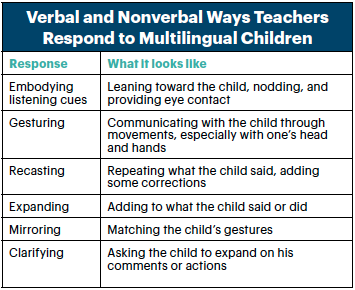

Ms. Alyson and children having a conversation as they make

bread pudding together.

The educators I observed consistently used relevant and meaningful objects—such as paintbrushes, puppets, spoons, and pictures—when they invited multilingual children to join activities. While pointing to or holding up an object, teachers often coupled an invitation with a question. During the activity, the children could see the topic of conversation and could contribute nonverbally by pointing to or moving the object (instead of trying to rely solely on words). This supported the children’s participation and conceptual development, and their motivation to communicate and complete the task. Because there were multiple members in the group working together, communication was required to accomplish the goals of the activity.

A child pours ingredients to

make bread pudding with his

classmates.

Examples of activities I observed included jointly painting fabric, preparing food and cooking, and acting out pictures from a multilingual text. These types of conversations with activities supported by relevant objects have been shown to facilitate children’s comprehension and engagement (Hamilton 2014; DiGiacomo & Gutiérrez 2016).

Relationships with family members are fundamental to the Children’s Center’s philosophy. Educators welcome family members to join classroom activities. The small group format lends itself to having family volunteers in class, sharing their expertise and aspects of their linguistic and cultural backgrounds. For example, during a multilingual book reading activity I observed, Ms. Kristi asked a child whose family was from Argentina how to say crab in Spanish. The child paused to remember, and Ms. Kristi suggested, pointing, “Ask your mom. She is right there.” The child looked to her mom, who said, “Cangrejo,” and the child repeated cangrejo, smiling and adding, “I have that music,” referring to a song they listened to at home.

3. Coparticipate in activities

The educators participated in activities with the children for an extended period of time (15 minutes or longer). Coparticipating enabled the teachers to provide ongoing and responsive assistance as compared with briefly visiting groups while rotating around the classroom or engaging children in a whole group setting. Joining the activities increases opportunities for educators and children to provide feedback to one another, which is essential to the learning process (DiGiacomo & Gutiérrez 2016). Educators can listen to, assess, and assist children’s developing conceptual and linguistic understandings. For example, I observed Ms. WenDee working with a small group of 2-year-olds to make pretzels. A multilingual child in the group confused the words for flour and sugar. In response, Ms. WenDee paused the mixing activity to have the children taste both ingredients and discuss the substances’ similarities and differences.

Children’s responses when teachers paint, draw, or cook along with them can be surprising. Coparticipating in activities with children naturally leads to modeling. It encourages more participation and helps teachers ask more open-ended and contextualized questions than when overseeing from the sidelines or just dropping in to ask questions. Multilingual children tend to watch their teachers and peers for nonverbal cues about what they are supposed to be doing and saying.

Coparticipating in activities with children encourages more participation and helps teachers ask more open-ended and contextualized questions.

When teachers and multilingual children coconstruct a product, they often also coconstruct a conversation. Such interaction constitutes “language learning in progress” (Swain 2013, 6). Collaborating on a joint product requires the contributors to discuss the steps using all of their language resources to negotiate meaning and arrive at mutual understanding. For example, a reoccurring joint activity at the Center is removing worm castings (to be used later in a classroom garden) from a composting bin. The activity requires separating the worms from the castings and then replacing the worms in the bin with fresh newspaper. I observed Mr. Raymond collaborate on this task with three 4-year-old children. Mr. Raymond started the activity by putting on plastic gloves and laying out newspaper. As he worked, three children came to observe him, and he invited them to help. They put on plastic gloves and listened attentively as Mr. Raymond described how to handle the worms gently and put them back in the bin with moist paper. While the children worked, they asked questions about the worms’ habitat, the moistness of the paper, and how to care for living things. By being a part of the action instead of just observing from the sidelines, educators can serve as a bridge to the activity for multilingual children and promote their interaction with other children.

4. Use small groups

Encourage other children to join in activities, but limit group sizes to no more than six. Small group settings help make an activity more conversational, relieving some of the performance pressure children may feel when in a whole group setting or one-on-one with an educator. Also, peer modeling and support can promote multilingual children’s language development and engagement (Ohta 2000). In the painting interaction described previously, Cody provided conceptual assistance to Kisho by making statements like, “That’s how you dye colors.” Small groups encourage multilingual children to take risks, such as verbalizing more often and asking questions, as was the case with Kisho while painting with Cody and Ms. Rheta. Language is learned through use, so children need ample opportunities to practice speaking and negotiating meaning (Gibbons 2015). Kisho was motivated to ask questions and to talk about the berries the dye was made from because he was curious and wanted to know if they were edible. He was comfortable verbalizing in this setting, and the group size allowed Ms. Rheta time to hear and respond to his questions. Multilingual children are likely to watch how you interact with others, and your responsiveness can help them feel valued.

Consider the seating arrangement when designing small group activities. Experiment with different arrangements and notice how the children respond. Some may contribute more to the conversation when they are right next to you. Other children may prefer direct eye contact from you to cue them to contribute, so having them across from you may promote their participation. Things like culture, family norms, personal preferences, and gender can influence how children engage in conversation. This is a great time to be a teacher-researcher and notice ways you can adjust the seating to encourage multilingual children’s engagement.

At the center, the children are free to join and leave small group activities as they wish; however, the teachers will invite some children to join groups based on the teachers’ learning goals. For example, it may be advantageous to have multiple children in the group who speak the same home language so they can support one another’s conceptual understanding through use of their familiar language. At other times, it may be helpful to include peers with more advanced English.

All of the educators I interviewed emphasized the importance of establishing classroom values with the children at the beginning of the year that are reinforced daily. These values emphasize helping one another, accepting mistakes, and being kind. The educators embody respect through their use of an inclusive pedagogy that actively elicits children’s contributions and builds on their interests and backgrounds; this promotes positive interactions and respectful behavior from the children.

5. Respond to children’s contributions

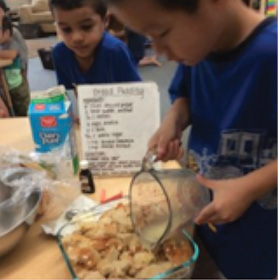

The educators at the center were masterful at responding to the multilingual children’s attempts to communicate. The table below summarizes the verbal and nonverbal responses to the children that teachers used frequently.

Responding to children’s contributions promotes engagement and learning. For example, recasting during educator–child interactions can benefit multilingual children’s language learning (Tsybina et al. 2006). During a pretzel-making activity, Dominic said as he rolled out his pretzel dough, “I rolling round.” Ms. WenDee responded by recasting his comment as a question, “Are you rolling it?” That was helpful because it modeled a grammatically correct question; an even more helpful recasting would have also included the vocabulary word dough, as in “Are you rolling the dough?” Ms. WenDee also mirrored the children’s gestures, communicating a shared understanding of the concepts in a nonverbal way. At one point, Dominic was counting the three ingredients on his hand; Ms. WenDee mirrored the gesture by holding up the same three fingers, touching them to the child’s, and saying, “I have the same as you.”

“Language learning is not just a cognitive struggle, it is a cognitive and emotional struggle” (Swain 2013, 11). Being responsive ensures that teachers build on children’s thinking and communicates that the teachers value children’s ideas, questions, and concerns. One way to study your responsiveness to multilingual children, including how you are communicating verbally and nonverbally, is to have a colleague videotape your interactions. Notice your facial expressions, gestures, eye contact, and tone of voice as you engage with the multilingual children.

Multilingual families and children should have opportunities to serve as experts and contribute to all of the children’s learning.

Responding to the children’s comments, questions, and body language (such as puzzled looks or gestures) will enable you to make links between the activity and what was interesting to the children. Being responsive helps make instruction relevant and meaningful. For example, during the painting activity referenced earlier, Kisho asked Ms. Rheta, “Kore nani ireta?,” which means “What did you put in this?,” regarding the paint. Ms. Rheta stopped and responded by gesturing and repeating the word “berries.” She then elaborated, gesturing in a picking motion while telling Kisho that a group of children picked the berries from a nearby tree. Ms. Rheta brought out her camera and showed Kisho photos from the berry picking to support his understanding. During our interview, Ms. Rheta told me that the learning goal for the activity was to help the children understand how certain things, like dye, can come directly from nature. Ms. Rheta responsively used Kisho’s questions as an opportunity to address the learning goal.

Conclusion

Research and observations of effective educators indicate that coparticipating with multilingual children in small group conversations centered on a joint activity, responding verbally and nonverbally to children’s contributions, and using the children’s home languages as a tool for understanding are ways to promote their engagement and learning. Instructional conversations give multilingual children opportunities to share their expertise and thoughts, promoting language development (Institute of Educational Sciences 2006; Chapman de Sousa 2017; Portes et al. 2017). Central to these strategies is creating opportunities for children to speak and share their ideas, solve problems together, and value diversity.

Bonus Strategy: Engaging Multilingual Families

To encourage the engagement of families from diverse backgrounds, educators at the center conduct home visits and have meetings with family members throughout the year. The initial family meeting is essential to relationship building. Educators ask important questions about the children and their preferences, and learn key words in the children’s home languages. From that first meeting onward, the center communicates to families that family members have expertise and that the program welcomes their contributions. Teachers use families’ unique knowledge and skills to develop the curriculum for the year. In addition to issuing in-person invitations, teachers send notes home asking families to come into the classroom and host activities.

During one of my visits, Ms. Amy, an educator at the center who worked with 2-year-olds, was having a conversation about butterflies with several multilingual children. She reminded a child that her mom would be coming into classroom to teach them songs in Japanese about butterflies. The child then said in English, “Mom is gonna bring us a song about butterflies,” an important multiword utterance for a 2-year-old who is just starting to learn English.

This type of meaningful engagement of families from diverse backgrounds has been shown to positively influence educational outcomes (O’Donnell & Kirkner 2014). Effective engagement efforts go beyond the traditional methods of having back-to-school nights and communicating only during parent–teacher conferences or when a behavior issue arises. At the center, multilingual families and children have opportunities to serve as experts and contribute to all of the children’s learning.

References

Chapman de Sousa, E.B. 2017. “Promoting the Contributions of Multilingual Preschoolers.” Linguistics and Education 39: 1–13.

DiGiacomo, D.K., & K.D. Gutiérrez. 2016. “Relational Equity as a Design Tool within Making and Tinkering Activities.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 23 (2): 141–53.

Doherty, R.W., R.S. Hilberg, A. Pinal, & R.G. Tharp. 2003. “Five Standards and Student Achievement.” NABE Journal of Research and Practice 1 (1): 1–24.

García, O., & L. Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gibbons, P. 2015. Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: Teaching Second Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. 2nd ed. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hamilton, R. 2014. “Bedtime Stories in English: Field-Testing Comprehensible Input Materials for Natural Second-Language Acquisition in Japanese Pre-School Children.” Journal of International Education Research 10 (3): 249–54.

Hilberg, R.S., R.G. Tharp, & L. DeGeest. 2000. “The Efficacy of CREDE’s Standards-Based Instruction in American Indian Mathematics Classes.” Equity and Excellence in Education

33 (2): 32–40.

Institute of Educational Sciences. 2006. “Instructional Conversation and Literature Logs.” What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) Intervention Report. Rockville, MD: WWC.https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/InterventionReports/WWC_ICLL_102606.pdf.

Justice, L.M., A.J. Mashburn, B.K. Hamre, & R.C. Pianta. 2008. “Quality of Language and Literacy Instruction in Preschool Classrooms Serving At-Risk Pupils.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23 (1): 51–68.

Mashburn, A.J., R.C. Pianta, B.K. Hamre, R.T. Downer, O.A. Barbarin, D. Bryant, M. Burchinal, R. Clifford, D.M. Early, & C. Howes. 2008. “Measures of Classroom Quality in Prekindergarten and Children’s Development of Academic, Language, and Social Skills.” Child Development 79 (3): 732–49.

O’Donnell, J., & S.L. Kirkner. 2014. “The Impact of a Collaborative Family Involvement Program on Latino Families and Children’s Educational Performance.” School Community Journal 24 (1): 211–34.

Ohta, A.S. 2000. “Rethinking Interaction in SLA: Developmentally Appropriate Assistance in the Zone of Proximal Development and the Acquisition of L2 Grammar.” Chap. 2 in Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning, ed. J.P. Lantolf, 51–78. New York: Oxford University Press.

Portes, P.R., M. González Canché, D. Boada, & M.E. Whatley. 2017. “Early Evaluation Findings from the Instructional Conversation Study: Culturally Responsive Teaching Outcomes for Diverse Learners in Elementary School.” American Educational Research Journal 55 (3): 488–531.

Ruston, H., & P.J. Schwanenflugel. 2010. “Effects of a Conversation Intervention on the Expressive Vocabulary Development of Prekindergarten Children.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 41 (3): 303–13.

Santa Ana, O. 2004. Tongue-Tied: The Lives of Multilingual Children in Public Education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Saunders, W., & C. Goldenberg. 2007. “The Effects of an Instructional Conversation on English Language Learners’ Concepts of Friendship and Story Comprehension.” In Talking Text: How Speech and Writing Interact in School Learning, ed. R. Horowitz, 221–52. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Swain, M. 2005. “The Output Hypothesis: Theory and Research.” In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning, ed. E. Hinkel, 471–84. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Swain, M. 2013. “The Inseparability of Cognition and Emotion in Second Language Learning.” Language Teaching 46 (2): 195–207.

Tharp, R. 1982. “The Effective Instruction of Comprehension: Results and Description of the Kamehameha Early Education Program.” Reading Research Quarterly 17 (4): 503–27.

Tharp, R., & S. Entz. 2003. “From High Chair to High School: Research-Based Principles for Teaching Complex Thinking.” Young Children 58 (5): 38–44.

Tsybina, I., L.E. Girolametto, E. Weitzman, & J. Greenberg. 2006. “Recasts Used with Preschoolers Learning English as Their Second Language.” Early Childhood Education Journal 34 (2): 177–85.

Yamauchi, L.A., S. Im, & N.S. Schonleber. 2012. “Adapting Strategies of Effective Instruction for Culturally Diverse Preschoolers.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 33 (1): 54–72.

Yamauchi, L.A., S. Im, C.-J. Lin, & N.S. Schonleber. 2012. “The Influence of Professional Development on Changes in Educators’ Facilitation of Complex Thinking in Preschool Classrooms.” Early Child Development and Care 183 (5): 689–706.

Photographs: 1 © Getty Images; 2, 3, 4, 5, courtesy of the author

E. Brook Chapman de Sousa, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa who focuses on supporting educators in their work with multilingual children. She is a former early childhood educator and instructional coach for CREDE Hawaiʻi.