Learning Targets: Helping Kindergartners Focus on Letter Names and Sounds (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Andrew J. Stremmel, Voices Executive Editor

In the following article, reading intervention teacher Heidi Heath DeStefano reflects on her struggles to help children learn letter names and sounds. She then sets out to conduct research to determine if establishing learning targets motivates and focuses the children in learning letters and sounds of the alphabet. Like all teachers who seek to be effective, she wants to help children learn, be engaged, and take ownership of their learning. Her study is guided by a theory of action, a comprehensive review of the literature, and a strategic process of instruction and assessment that is monitored, recorded, and reflected upon systematically and intentionally.

The first and arguably most important step in the teacher research process is identifying a problem of meaning (something that puzzles or perplexes). The problems and dilemmas of teaching are all around: as Heidi demonstrates, problems arise from an interest in finding out more about one’s teaching, or about how children learn or attempt to understand; while trying to develop some new teaching method; or when faced with needing to make a decision and act upon it. Heidi’s research represents a distinctive way of knowing about teaching and learning that alters not only her teaching practice and understanding of children’s learning (in this case an ability to internalize learning goals) but also her notion of what it means to be a learner in her own classroom. Here, she reflects deeply on the value of learning goals and gains insights into the need to teach more intentionally and responsively.

Teacher research, at its best, is a good story that begins with something we wonder about—something that perplexes or astonishes us—and ends with something we want to make known. It always leaves us with the questions What did I learn? and What can I change or do differently? These questions and conclusions are what make teacher research a vehicle for change, transformation, and improvement.

As a reading intervention teacher in an elementary school, one of my responsibilities is to help students fill in their learning gaps. Struggling readers often come to me with negative attitudes toward reading, so I need to present learning activities in creative ways in order to capture their interest.

One teaching assignment I had was to help a group of 11 very active kindergartners learn letter names and a subset of letter sounds. After several weeks of engaging the children in a variety

of letter-acquisition activities—most of which I drew from my school district’s literacy programs—the assessment information revealed that my instruction was not making a significant impact on student learning. More alarming, I noticed the children were not motivated to learn the letters or to answer accurately when I assessed them. For example, they were using the magnetic letters as toys, and I was spending more time on behavior management than on teaching. I found that activities like sorting letters and tracing letters in sand helped keep students from rough and tumble play, but these activities were not bringing them any closer to the instructional objective.

I realized I had not effectively conveyed the purpose of our intervention sessions. Consequently, I needed to find a way to focus their efforts and encourage them to take ownership of their learning.

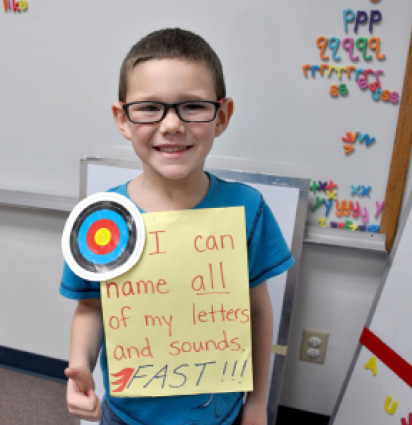

In professional development sessions, my school district had begun training teachers on providing students with clear statements of intended learning outcomes when we introduced new units or activities. These outcomes provide a shared direction: different students may take different paths (building on their unique prior experiences), but they all end up mastering the same essential knowledge and skills. I challenged myself to adapt the idea of a learning outcome in a format these kindergartners would relate to. I decided to attach the statement, “I CAN NAME ALL OF MY LETTERS AND SOUNDS,” to a colorful 10-ring target and refer to it as a learning target.

In the past, I had goals for my lessons, but I had never tried anything this explicit to engage the kindergartners in thinking about the goals. Since this was a new strategy for me, I approached the work as both a teacher and a researcher. I mapped out a study to determine if the learning target would motivate the children to shift from rough and tumble play to focused learning. I was still going to use playful activities and games, but I hoped that the children’s attention and thinking would shift if I could guide them more clearly on the purpose of our sessions.

Literature review

Prompted by education researcher Robert J. Marzano (2003), who explains that when students can identify what they’re learning, they significantly outscore students who cannot, my research on using learning outcomes began with two sources: Learning Targets: Helping Students Aim for Understanding in Today’s Lesson (Moss & Brookhart 2012) and Visible Learning for Literacy: Implementing the Practices That Work Best to Accelerate Student Learning (Fisher, Frey, & Hattie 2016).

The learning target theory of action in Learning Targets involves using clear, student-friendly descriptions of what students will learn, then incorporating a cycle of instruction, monitoring, and assessing until they reach their goals (Moss & Brookhart 2012). Learners are actively engaged with the teacher in this cycle. As an experienced teacher, the reasoning behind setting targets resonated with me: “no matter what we decide students need to learn, not much will happen until students understand what they are supposed to learn during a lesson and set their sights on learning it” (Moss, Brookhart, & Long 2011, 1).

Visible Learning for Literacy (Fisher, Frey, & Hattie 2016) offers similar advice, suggesting that teachers need to set learning intentions and provide success criteria. After a comprehensive review of the literature, the authors found that instructional strategies that incorporate key aspects of learning intentions—such as teacher clarity, formative assessment, and prompt feedback—are among the top 10 most effective ways to increase student achievement. Much like the cycle described in the learning target theory of action, the keys with learning intentions are clarity in goals, monitoring progress (i.e., formative assessment, which may be teacher-made quizzes or other means of determining students’ recent learning), and feedback that is timely enough to guide the teacher and learners. This feedback loop allows teachers to use information from formative assessments to adjust instruction and reteach material so students meet their learning objectives before their final evaluations. (Or, in the case of my kindergartners, before they became frustrated and started to worry that they wouldn’t be able to learn to read.) Focusing on how feedback supports learners’ self-efficacy, the authors discuss “three internal questions that drive learners”:

- Where am I going? What are my goals?

- How am I going there? What progress is being made toward the goal?

-

Where to next? What activities need to be undertaken next to make better progress?

(Fisher, Frey, & Hattie 2016, 101)

These ideas about clear goals and actionable feedback are not new. Four decades ago, Benjamin Bloom found a similar instructional cycle to be quite effective. While searching for methods of group instruction as effective as one-on-one tutoring, he showed that mastery learning (an approach that combines typical large-group instruction with frequent assessments, timely feedback, and customized supports) significantly improved students’ learning compared with conventional methods (in which assessments are only given at the end of a unit to provide grades). Although mastery learning conducted with the whole class was not as effective as one-on-one tutoring, it was nearly as effective and far more efficient (Bloom 1984).

Adapting this body of research for the kindergarten intervention group, I hoped to dramatically increase the impact of my instruction on the students’ learning.

Studying the effect of learning targets with kindergartners

The existing literature convinced me that learning targets are important, but much of the research has been done with older children. I was interested in answering the following questions:

- Would the kindergartners in my reading intervention class understand the concept of a learning target?

- Would using the learning target help motivate the students to take ownership of their learning and aid them in acquiring the letters and sounds of the alphabet?

- If using a learning target were successful for the students’ alphabet learning, could it be used for other concepts?

Setting and participants

The elementary school where I conducted this action research study is located in a small, predominantly white and middle-class community in Wyoming. In recent years, we have enrolled one or two Hispanic children who speak Spanish and English in each classroom, but who often need English vocabulary development (DeStefano 2017). The demographics of our school are gradually changing: the school has long served children whose parents are well-educated professionals and is now serving a larger proportion of children from working-class families.

The learning environment for this study was my small intervention room, containing a table, magnetic whiteboards propped around the room, and a few storage closets on which I often post word lists.

The children became more enthusiastic as they took ownership of their learning.

My teaching schedule included three kindergarten reading intervention groups with three to five students in each group, for a total of 11 students (four girls and seven boys). Two of the children spoke Spanish and English (neither qualified for dual language learner services); the remaining nine children only spoke English. All 11 children were identified by their regular classroom teachers as needing extra instruction to master letter names and sounds.

My study of the learning target approach (which I explain in detail in the following sections) spanned nine weeks. I met with each of the small groups for 15 to 20 minutes a day, four to five days per week.

Data collection

Throughout the study, I collected three types of data:

- A letter-naming assessment that consisted of a random assortment of all uppercase and lowercase letters, plus typewritten g and a. This resulted in 54 letters that the children had to be able to name to meet this part of the target.

- A sound identification assessment that consisted of a random assortment of all uppercase and lowercase letters, plus typewritten g and a, resulting in 54 letters for which the children had to provide sounds. I was teaching and assessing one sound for each consonant (e.g., /k/ for C and c) and the short vowel sounds; therefore, the children needed to learn just one sound for each letter during this intervention.

- My observations of the students’ reactions to the intervention.

I met with each group of children and showed them the colorful 10-ring target posted on the wall of our room. We discussed that the purpose of a target is to help us practice getting a bull’s-eye. Then we discussed that the bull’s-eye in our classroom was to name all of the letters and their main sounds. (I also briefly explained that they would learn more sounds in first grade and that in kindergarten, we were learning the most important sounds that each letter makes.) I modeled what meeting the target looks like, pointing to each letter in a randomly sorted list and quickly saying the name and associated sound. I told the students that the purpose in this learning space was to aim for our target: “I CAN NAME ALL OF MY LETTERS AND SOUNDS.” At the beginning and end of each session, we reviewed this target by saying it aloud as I pointed to the words.

After my initial explanation of the learning target, I assessed each child on the letter names and sounds to determine which ones each child already knew. On the average, students named 41.5 out of 54 letter names and 32 out of 54 letter sounds.

Next, I met with each student individually and we discussed which letter names and sounds they needed to acquire in order to reach the learning target. I created customized little booklets containing the letters to be learned by each child and discussed the specific activities that would help them learn those letters.

Every week, I administered the same assessments to each available student individually and discussed his or her progress. During this feedback discussion, I prompted the children to think about the questions that drive learners, from “Where am I going?” to “What activities need to be undertaken next to make better progress?” (Fisher, Frey, & Hattie 2016, 101). (While I met with children individually, the others in the group engaged in the learning activities I provided, focusing their efforts on the letters they personally needed to acquire.) To help motivate the children, I was sure to find some progress in each assessment. After the assessments, we celebrated as a group. As I stated what a child had accomplished that week, the child got to throw a small pillow at our target. When a student correctly provided a letter’s sound and name, there was an added celebration: we dramatically ripped that page out of the booklet.

As a standard teaching procedure, I took notice of the students’ comments and observable behaviors. I recorded my observations on a daily basis as short, anecdotal notes. I maintained a record for each child so that I could efficiently track progress. Using my observations and weekly assessments, I created the little booklets that contained the specific letters each child needed to learn and planned the activities that would help them learn those letters. My notes also helped me be more specific with my feedback, and I could more easily relate the children’s efforts to their success.

Findings

Within the first week of implementation, it appeared that the learning target would be highly effective. I felt rising elation as I saw the children becoming more enthusiastic and motivated as they took ownership of their learning. Assessment scores also steadily improved.

One child immediately understood his purpose for being with me and met his goal early on in the intervention. Discussing his strengths and needs with his teacher, we agreed that he was overall doing well in learning to read and therefore not in need of additional interventions. I had him return to his classroom, victorious. Another boy noticed and asked, “Hey! Where is he going?” In response, I asked, “Why are we all working so hard in my room?” He repeated what we had been saying every day when we entered the class: “We are here because we need to learn to name all of our letters and sounds.” I told him, “He hit the bull’s-eye, so he is going back to his classroom to work on other things.” After thinking for a moment, he set his mouth in a firm line and went to work on his activity with obvious resolve. It took a while, but all of the children finally understood that everyone in our school is required to know their letters and sounds—“even the principal,” as we often said while making the connection to learning to read and write (Duke & Mesmer 2018).

Finding 1: Every child acquired knowledge of the letter names and sounds

Based on the weekly assessment scores, by the end of my nine-week study, every child could name all the letters (uppercase and lowercase, plus typewritten g and a) and virtually all of the target sounds—just one student lacked one letter sound. For both letter names and sounds, the kindergartners’ knowledge increased sharply in the first four to five weeks and most of the children had reached the target by week six.

Finding 2: The children understood the connection between effort and outcome and were able to focus their efforts

While it may seem redundant to ask students to state the learning target before each session, to review it and their progress at the end of each session, and to individually assess the children and discuss the target every week, I found that repetition was required for the children to internalize the purpose of their presence in the intervention room. Although I was surprised by how explicit and repetitive I needed to be, I also saw it working. As understanding of their learning target deepened, the students engaged in far less unfocused play and became determined to reach their learning target. During our discussions, I repeatedly reinforced the connection between their efforts and their successes. Students were able to understand the connection between their work and their expanding knowledge of the alphabet. My observations are consistent with prior research indicating that teachers who focused on formative assessment saw an increase in students’ learning, self-efficacy, and self-regulation (Brookhart, Moss, & Long 2008).

Finding 3: The children understood that using learning targets can be a lifelong strategy and were able to identify personal goals

The children found the novelty of throwing a small pillow at the target to celebrate progress highly motivating. Just as I was careful to note the specific progress that each child made, I also explicitly tied this sought-after event to the cause and effect relationship of goal-setting, practice, feedback, and success.

Once this understanding was solid, we discussed that anyone, at any age, can have a learning target. I told them about my personal learning target of speaking another language fluently, and I shared a few of the activities I was doing to reach it. Each student identified a personal learning target and we brainstormed ways they could work toward them. For example, one child wanted to learn how to make his own sack lunch and another wanted to ride a bike without training wheels.

After students obtained their alphabet learning target (which virtually all of the children did by week six), I introduced a new target for reading: “I CAN MAKE WHAT I SAY MATCH WHAT I SEE.” This new target would help students focus on each letter so they could accurately decode the text in their books. The concept of a learning target was easier for students to understand with the second target, and once again it seemed to enhance their learning.

When the school principal asked me if I had any celebrations that could be presented at the monthly school board meeting, I could barely contain my enthusiasm! The students and their families stood in front of the school board a month later, and we proudly presented their achievements along with their personal learning targets. Before the learning target intervention, I would have been worried about bringing my rambunctious kindergartners to a school board meeting, but the pride they felt for their achievements was strong, and they conducted themselves with dignity.

Finding 4: Learning targets benefitted families, older students, and myself

Using learning targets to help motivate and focus the children was well received by families from the beginning. Throughout, seeing their children’s excitement and growing confidence as they worked toward and reached a goal was positive for the whole family.

Because of this success, I also began using learning targets with my older students, and it worked well with all of my reading intervention groups. I believe the targets helped me as much as the children because creating the learning targets aided in focusing my instruction. I gave myself the professional learning target of providing a learning target for each new concept to be taught!

Implications

A great deal of evidence indicates that different approaches are needed for different students and situations and that teachers must adjust instruction to meet the needs of their students (Fisher, Frey, & Hattie 2016). When first working with these energetic kindergartners, I began to think they might not be developmentally ready to learn letter names and sounds. It was an eye-opening teaching experience to witness how, given a clear and motivating learning target, unfocused children became strategic learners in a positive and fun way. In addition, I am hopeful that establishing the process of setting a goal, working strategically toward that goal, and celebrating success at the beginning of students’ academic careers will set them up to repeat this pattern of success in the future. After all, research shows that self-efficacy as a learner (“the confidence or strength of belief that we have in ourselves that we can make our learning happen”) has a big impact on achievement (Fisher, Frey, & Hattie 2016, 24).

The increases I observed in my kindergartners’ self-regulation and self-efficacy have been reported in other studies (Brookhart, Moss, & Long 2008; Moss, Brookhart, & Long 2011). I’ve also learned I’m not the first teacher to use colorful 10-ring targets to represent learning objectives (Moss, Brookhart, & Long 2011). In my experience, goal-setting is a concept most teachers are familiar with, but in the struggle to focus my active kindergarten students, I had forgotten how powerful it can be. In light of this study, I now have effective methods for helping young children internalize learning goals.

This experience prompted me to do some deep reflecting on my teaching practice. I had been presenting activities without conveying strong learning goals. Had the students’ initial lack of focus mirrored my own? Had my teaching become a bit automatic over the years? Revisiting the effectiveness of learning goals and experiencing again how powerful they can be for children was an important learning touchstone for me. This, along with furthering my understanding of learning targets by studying research on the topic, helped return me to teaching intentionally and with greater responsiveness to children’s needs.

One unexpected result of this study is that I learned to be more culturally sensitive. During an activity in which students were using magnetic letters to match initial sounds to picture cards, a Hispanic student had placed the letter d in front of a picture of money. She stood, frustrated, staring at the remaining picture of a dog and then at the letter m in her hand. I asked her, “What is the first sound you hear in money?” Her eyes widened in comprehension, then narrowed as she drew herself up and proudly said, “WE call it dinero!” Because she spoke English, I had been instructing her without considering her cultural lens. She was magnificent, and I was humbled.

Using colorful 10-ring targets can make learning goals more concrete for young learners. My Wyoming students—many of whom come from hunting backgrounds and all of whom are familiar with hunting—were highly motivated by this particular visual. For students with different backgrounds, other visuals may resonate more strongly. However, the learning target theory of action is a research-based tool teachers can consider when designing instruction to have greater impact on student self-regulation, self-efficacy, and learning.

References

Bloom, B.S. 1984. “The Search for Methods of Group Instruction as Effective as One-to-One Tutoring.” Educational Leadership 41 (8): 4–17.

Brookhart, S., C.M. Moss, & B. Long. 2008. “Formative Assessment That Empowers.” Educational Leadership 66 (3): 52–57.

DeStefano, H.H. 2017. “Supporting Struggling Readers: Using Vocabulary Cartoons During Transition Times.” Young Children 72 (5): 64–72.

Duke, N.K., & H.A.E. Mesmer. 2018. “Phonics Faux Pas: Avoiding Instructional Missteps in Teaching Letter-Sound Relationships.” American Educator 42 (4): 12–16. https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2018-2019/duke_mesmer.

Fisher, D., N. Frey, & J. Hattie. 2016. Visible Learning for Literacy: Implementing the Practices That Work Best to Accelerate Student Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Marzano, R.J. 2003. What Works in Schools: Translating Research Into Action. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Moss, C.M., S.M. Brookhart, & B.A. Long. 2011. “Knowing Your Learning Target.” Educational Leadership 68 (6): 66–69.

Moss, C.M., & S.M. Brookhart. 2012. Learning Targets: Helping Students Aim for Understanding in Today’s Lesson. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Heidi Heath DeStefano, MEd, has taught kindergarten and first grade and is currently a Reading Recovery teacher at Pronghorn Elementary, in Gillette, Wyoming. [email protected]